The “War to end all Wars” exploded across the European continent in the summer of 1914, devolving into the stalemate of trench warfare, by October.

The ‘Great War’ became Total War, the following year. 1915 saw the first use of asphyxiating gas, first at Bolimow in Poland, and later (and more famously) near the Belgian village of Ypres. Ottoman deportation of its Armenian minority led to the systematic extermination of an ethnic minority, resulting in the death of ¾ of an estimated 2 million Armenians living in the Empire at that time. For the first time and far from the last an unsuspecting world heard the term, genocide‘.

Kaiser Wilhelm responded to the Royal Navy’s near-stranglehold on surface shipping with a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare, as the first zeppelin raids were carried out against the British mainland. German forces adopted a defensive strategy on the western front, developing the most sophisticated defensive capabilities of the war and determined to “bleed France white”, while concentrating on defeating Czarist Russia.

Russian Czar Nicholas II took personal command that September, following catastrophic losses in Galicia and Poland. Austro-German offensives resulted in 1.4 million Russian casualties by September with another 750,000 captured, spurring a “Great Retreat” of Russian forces in the east and resulting in political and social unrest which would topple the Imperial government, fewer than two years later. In December 1915, British and ANZAC forces broke off a meaningless stalemate on the Gallipoli peninsula, beginning the evacuation of some 83,000 survivors. The disastrous offensive produced some 250,000 casualties. The Gallipoli campaign was remembered as a great Ottoman victory, a defining moment in Turkish history. For now, Turkish troops held their fire in the face of the allied withdrawal, happy to see them leave.

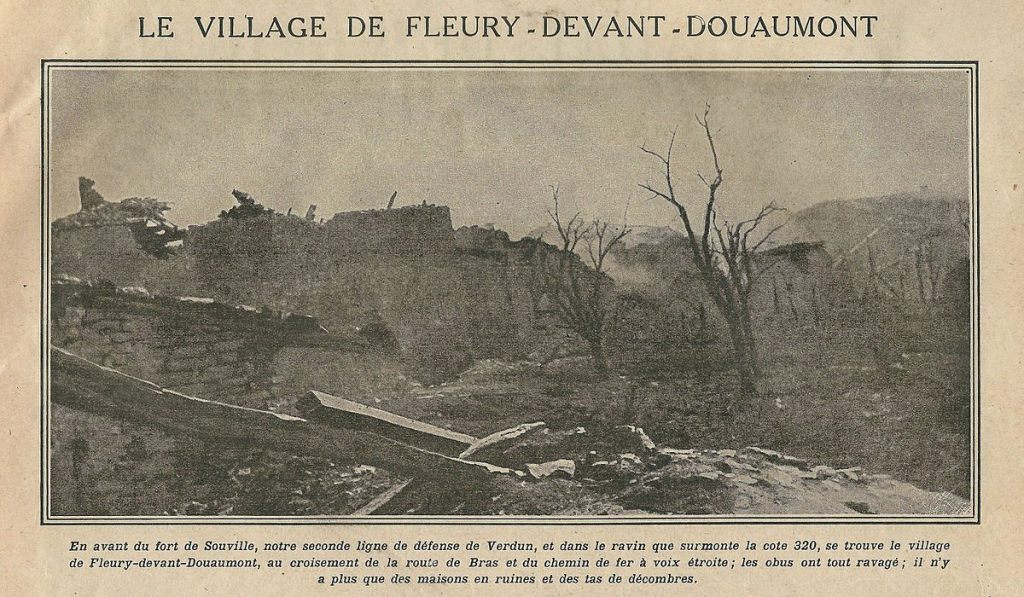

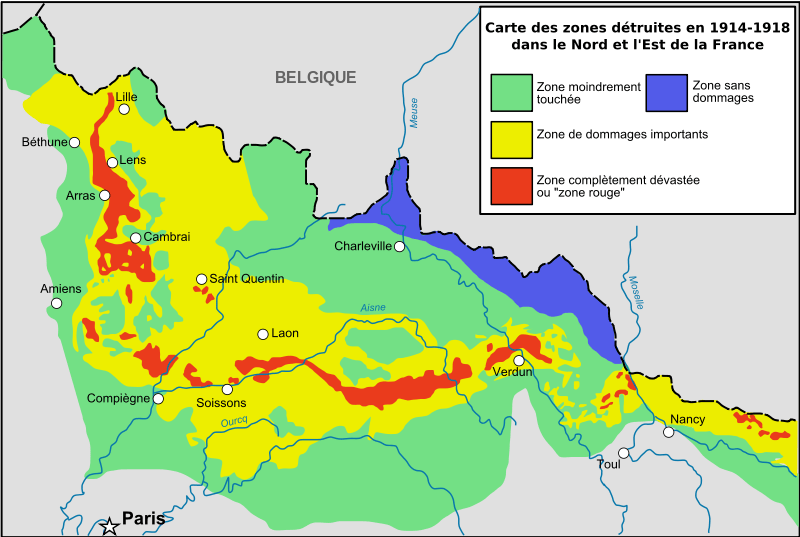

A single day’s fighting in the great battles of 1916 could produce more casualties than every European war of the preceding 100 years, civilian and military, combined. Over 16 million were killed and another 20 million wounded while vast stretches of the Western European countryside were literally torn to pieces.

1917 saw the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare, and a German invitation to bring Mexico into the war, against the United States. As expected, these policies brought America into the war on the allied side. The President who won re-election for being ‘too proud to fight’ asked for a congressional declaration of war, that April.

Massive French losses stemming from the failed Nivelle offensive of that same month (French casualties were fully ten times what was expected) combined with irrational expectations that American forces would materialize on the western front led to massive unrest in the French lines. Fully one-half of all French forces on the western front mutinied. It’s one of the great miracles of WW1 that the German side never knew, else the conflict may have ended, very differently.

The “sealed train‘ carrying the plague bacillus of communism had already entered the Russian body politic. Nicholas II, Emperor of all Russia, was overthrown and murdered that July, along with his wife, children, servants and a few loyal friends, and their dogs.

This was the situation in July 1917.

For eighteen months, British miners worked to dig tunnels under Messines Ridge, the German defensive works laid out around the Belgian town of Ypres. Nearly a million pounds of high explosive were placed in some 2,000′ of tunnels, dug 100′ deep. 10,000 German soldiers ceased to exist at 3:10am local time on June 7, in a blast that could be heard as far away, as London.

For eighteen months, British miners worked to dig tunnels under Messines Ridge, the German defensive works laid out around the Belgian town of Ypres. Nearly a million pounds of high explosive were placed in some 2,000′ of tunnels, dug 100′ deep. 10,000 German soldiers ceased to exist at 3:10am local time on June 7, in a blast that could be heard as far away, as London.

Buoyed by this success and eager to destroy the German submarine bases on the Belgian coast, General Sir Douglas Haig planned an assault from the British-held Ypres salient, near the village of Passchendaele.

British Prime Minister David Lloyd George opposed the offensive, as did the French Chief of the General Staff, General Ferdinand Foch, both preferring to await the arrival of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF). Historians have argued the wisdom of the move, ever since.

The third Battle of Ypres, also known as the Battle of Passchendaele, began in the early morning hours of July 31, 1917. The next 105 days would be fought under some of the most hideous conditions, of the entire war.

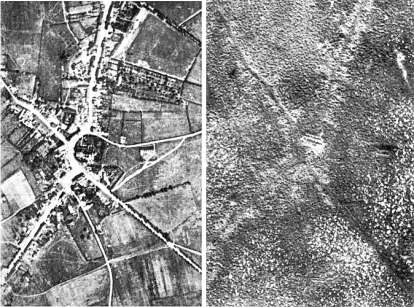

In the ten days leading up to the attack, some 3,000 guns fired an estimated 4½ million shells into German lines, pulverizing whole forests and smashing water control structures in the lowland plains. Several days into the attack, Ypres suffered the heaviest rainfall, in thirty years.

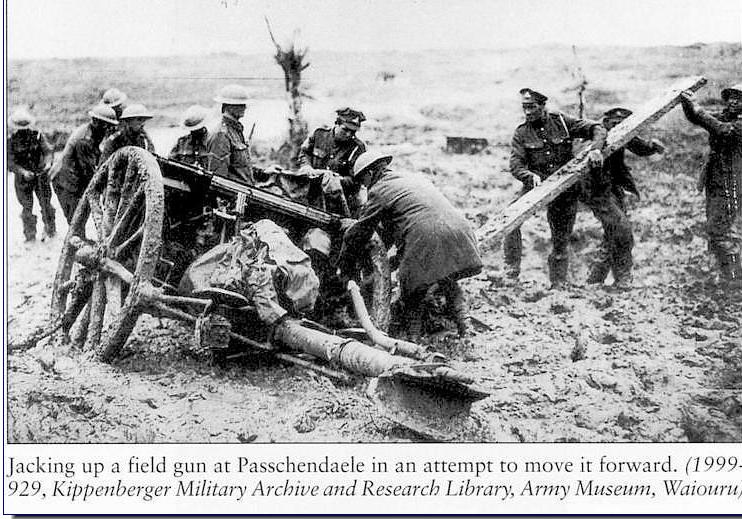

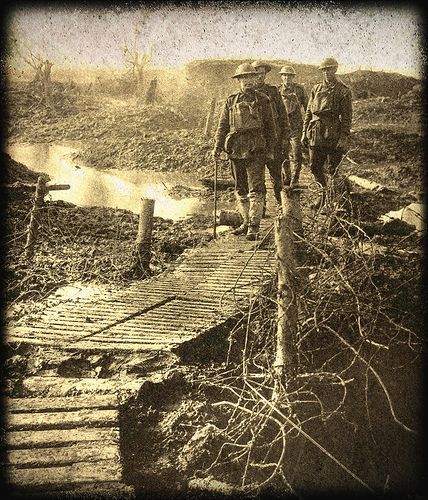

Conditions defy description. Time and again the clay soil, the water, the shattered remnants of once-great forests and the bodies of the slain were churned up and pulverized by shellfire. You couldn’t call the stuff these people lived and fought in mud – it was more like a thick slime, a clinging, sucking ooze, capable of swallowing grown men, even horses and mules. Most of the offensive took place across a broad plain formerly crisscrossed with canals, but now a great, sucking mire in which the only solid ground seemed to be German positions, from which machine guns cut down sodden commonwealth soldiers, as with a scythe.

Soldiers begged for their friends to shoot them, rather than being left to sink in that muck. One sank up to his neck and slowly went stark raving mad, as he died of thirst. British soldier Charles Miles wrote “It was worse when the mud didn’t suck you down; when it yielded under your feet you knew that it was a body you were treading on.”

In 105 days of this hell, Commonwealth forces lost 275,000 killed, wounded and missing. The German side another 200,000. 90,000 bodies were never identified. 42,000 were never recovered and remain there, to this day. All for five miles of mud and a village barely recognizable, following capture.

Following the battle of Passchendaele, staff officer Sir Launcelot Kiggell is said to have broken down in tears. “Good God”, he said, “Did we really send men to fight in That”?!

The soldier-turned war poet Siegfried Sassoon reveals the bitterness of the average “Joe Squaddy”, sent by his government to fight and die, at Passchendaele. The story is told in the first person by a dead man, in all the bitterness of which a poet decorated for bravery and later shot in the head by his own side, is capable. It’s called:

Memorial Tablet

Squire nagged and bullied till I went to fight,

(Under Lord Derby’s Scheme). I died in hell—

(They called it Passchendaele). My wound was slight,

And I was hobbling back; and then a shell

Burst slick upon the duck-boards: so I fell

Into the bottomless mud, and lost the light.

At sermon-time, while Squire is in his pew,

He gives my gilded name a thoughtful stare:

For, though low down upon the list, I’m there;

‘In proud and glorious memory’… that’s my due.

Two bleeding years I fought in France, for Squire:

I suffered anguish that he’s never guessed.

Once I came home on leave: and then went west…

What greater glory could a man desire?

You must be logged in to post a comment.