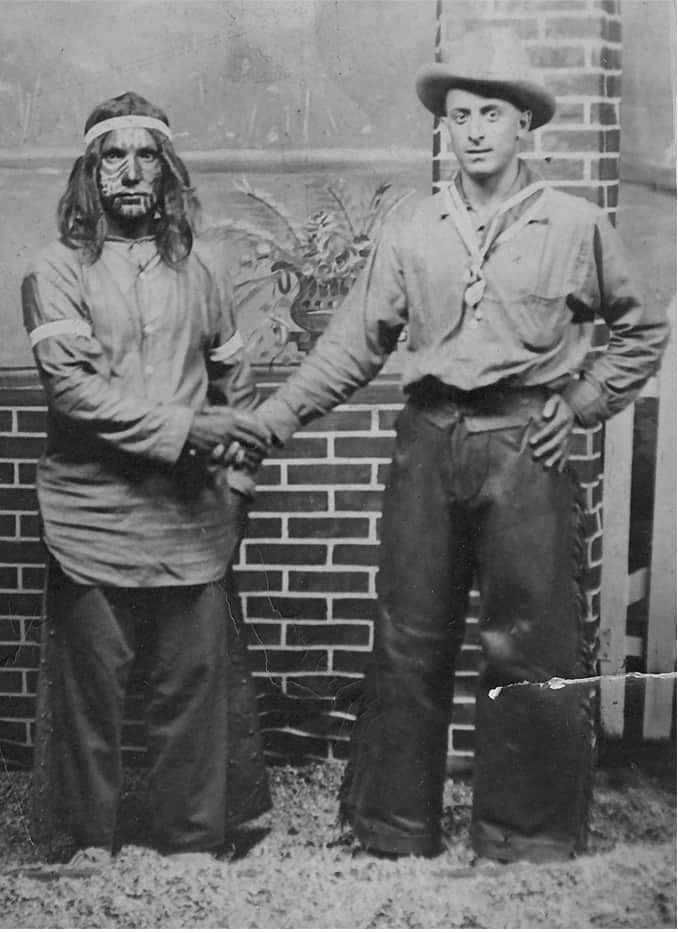

The Wild West gunfight is the stuff of American legend. A lone gunslinger rides down a dusty street. Townsfolk dive for shelter leaving two men standing. Only one can be the quickest draw. One man will walk away and another will die.

And yet these are movie images. If anything, the real gunfights of the wild west were uglier, more violent and less heroic than anything we ever saw on film. It was often hard to tell the good guys, from the bad.

So step aside Clint Eastwood, John Wayne. We’re here to talk about a real-life gunslinger, called “Wild Bill” Hickok.

James Butler Hickok was born in Homer Illinois in the present-day town of Troy Grove, the 4th of 6 children of William “Bill” Hickok and his wife, Pamelia “Polly” Butler Hickok. The family home is gone now but believed to be a stop on the “underground railroad”, a network of households offering refuge and assistance, to runaway slaves.

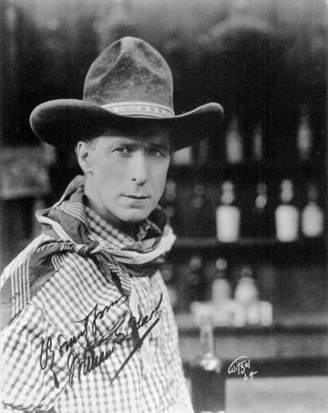

James learned from an early age to shoot a pistol. He was good at it. Photographs of the era depict him with dark hair but the age of photography, was in its infancy. Those who knew Hickok described the man, with red hair.

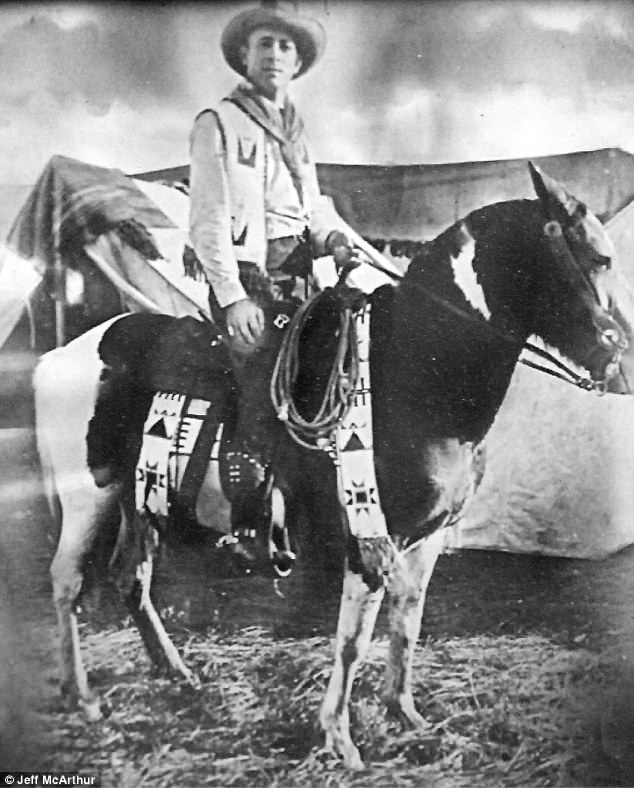

He was fifteen when his father died. At 18 he fled the Illinois territory after a fight, with one Charles Hudson. Both fell into a canal and believed (wrongly) he had killed the other man. He was attracted to the “Banditti of the prairie” lifestyle and took up with Jim Lane’s violently abolitionist Free State Army known as Jayhawkers, during the Bleeding Kansas era. There he met a 12-year-old who, despite his young age became a scout for the US Army, only two years later. We remember the boy today for the soldier, showman and bison hunter he would later become, Buffalo Bill Cody.

Hired as a stagecoach driver by the Russell, Majors and Waddell freight company, Hickok was driving a team from Independence, Missouri, to Santa Fe, New Mexico, when an incident with a cinnamon bear resulted in one dead bear, and four months in bed recovering from a crushed chest and a shoulder and arm, mangled in the melee.

Recovering from the bear incident, Hickok was sent to become a stable hand at the Rock Creek station, a stagecoach and Pony Express stop in the Nebraska territory.

David Colbert McCanles leased a well and a cabin to Hickok’s employer. The former sheriff of Watauga County, North Carolina, McCanles was a bully who didn’t like this newcomer, Hickok. He called the younger man “Duck Bill” for his large nose and protruding lips and derided the man’s slender, almost girlish build. McCanles’ mistress Sarah (Kate) Shull didn’t seem to mind any of it and became romantically involved, with Hickok.

You know where this is going, right?

McCanles arrived at the station with his cousin James Woods, another employee called James Gordon and his 12-year-old son, Monroe. Accounts vary but soon, there was a brawl. Hickok stepped from behind a curtain where he was hiding and shot McCanles, dead. He shot Gordon and Woods as well, one of whom was finished off with a shotgun blast by station employee J. W. “Doc” Brink and the other hacked to death with a garden hoe, either by Horace Wellman, or Wellman’s wife.

I did say these things could be ugly, right? As for 12-year-old Monroe, he managed to get away.

The trial lasted all of 15 minutes and ended in acquittal, based on self-defense. Hickok rode out to the McCanles home and told the widow he was sorry, he had killed her man. He gave her all the money in his pocket saying ‘This is all I have, sorry I do not have more to give you”. It was $35, equivalent to $1,056 today.

After the McCanles episode Hickok grew a moustache, to hide that protruding lip. He encouraged people to call him “Wild Bill”.

Surprising though it may seem to the modern reader, the “news” media, couldn’t always be trusted. According to George Ward Nichols of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, “Hundreds” of men lay dead at the smoking barrel of Hickok’s gun. Never mind that, everywhere Hickok was actually known his supposed death counts, were often disputed.

Like the rest of Wild Bill’s life his civil War service is shrouded in mystery. No scion of stout abolitionists would have missed an opportunity to serve, with the federal cause. He seems to have begun as a teamster, later rejoining now-General James Henry Lane’s Kansas brigade as provost marshal, basically military police. Some say he managed to infiltrate the other side as a spy. Buffalo Bill Cody claimed to have seen the man in 1964, wearing Confederate gray.

Hickok lived in an age when the good guys and the bad guys, were hard to tell apart. In 1869 the good folks of Ellis Kansas appointed Hickok, interim Sheriff. Tall, hard and imposing this was no longer the scrawny youth of his younger days. One cowboy described Hickok standing “with his back to the wall, looking at everything and everybody under his eyebrows — just like a mad old bull”.

As for “keeping the peace”, Hickok managed to kill two men in his first five weeks. He lost the election to his own deputy after three months on the job.

In Springfield Missouri, Hickok had several run-ins with a local gambler, called Davis Tutt. The two men had affection for some of the same women as well, and that’s never a good place to start. By 1865, gambling disputes had upped the ante to lethal levels.

Hickok was sentimental about a gold watch and lost it in a poker game, to Davis Tutt. He asked the man not to wear the thing in public but Tutt couldn’t resist, rubbing his nose in the loss. Hickok warned Tutt to stay away. That came to an end on July 21 in a scene, right out of the spaghetti western. The two men stopped in the street glaring, ever so slowly turning to the side, to provide a smaller target. Tutt drew first, and missed his target. Hickok’s bullet struck right through the heart. Tutt clutched his chest and cried out, “Boys, I’m killed” before he collapsed, and died. The “quick draw” duel has become the stuff of legend, but this was the first.

Judge Sempronius Boyd (how do you not love that name) instructed the jury they could not acquit, if there had been reasonable opportunity to avoid the fight. The unwritten doctrine of the “fair fight” however did apply, and the jury voted to acquit.

Wild Bill Hickok was the best gunfighter of his time but not always, the fastest draw. Tom Clavin’s book WILD BILL: The True Story of the American Frontier’s First Gunfighter claims Tutt drew first but Hickok…he didn’t miss.

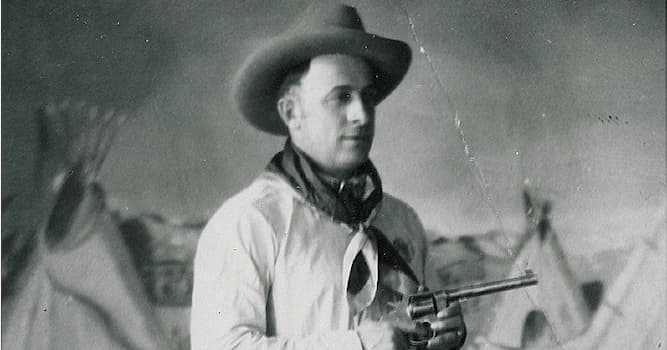

His favorite weapons were a pair of 1851 twin cap & ball navy revolvers he’d wear butt first and cross-draw, cavalry style. In an age when weapons were not always on target Hickok was cold as ice and took a moment to steady his aim. On top of that the man was ambidextrous and aimed as well with one eye, as the other.

Nothing lasts forever. For Wild Bill Hickok the beginning of the end came in 1871. As Marshall for Abilene Kansas Hickok’s methods were tried and familiar and understood if not liked, by all. It is said that Hickok had but three options for troublemakers. They could leave on the train going east or the one heading west. Or they could go north. If they didn’t already know they would find out soon enough. The town cemetery was located to the north.

On October 5, 1871 he had a terrible shootout with local saloon owner, Phil Coe. Hickok managed to kill Coe but turned like a flash and fired at a third man, sprinting toward him. Both bullets hit their mark, mortally wounding Hickok’s deputy and good friend, Mike Williams. Hardened as he was it’s said that he cried, as they carried his friend away to die.

James Hickok was a gambler, a gunfighter and a part-time law man, what the History of Greene County, Missouri later described as “by nature a ruffian … a drunken, swaggering fellow, who delighted when ‘on a spree’ to frighten nervous men and timid women.”

Mike Williams was the last man he would ever kill.

On August 1, 1876, Hickok was playing poker at Nuttal & Mann’s saloon in Deadwood, in the Dakota territory. A seat opened up and John “Broken Nose Jack” McCall joined the game. McCall started out drunk and he lost. Badly. Hickok encouraged McCall to quit the game until he could cover his losses and he gave the man money, for breakfast. McCall accepted the money but felt insulted. Next day he returned, intending to settle the score.

Hickok was once again at the table but this time, with his back to the door. Wild Bill Hickok always sat with his back to the wall but this time Charles Rich had that seat, and wouldn’t give it up. McCall strode into the saloon and drew his .45-caliber revolver shouting “Damn you, take that!”. The bullet entered the back of Hickok’s head from point-blank range and came out his right cheek before striking another player on the wrist. Wild Bill Hickok was dead before his head hit the table. He held two pair in his hand. Aces and eights, remembered from that day to this, as the “dead man’s hand”.

The 5th card hand is disputed and remains unknown, to this day.

Jack McCall was “tried” and acquitted by a loose collection of miners and local businessmen. He claimed to be avenging the death of his brother but there is no way to verify the story. McCall was re-arrested and re-tried, the second trial was held in Yankton, capital of the Dakota territory. Deadwood was at the time part of unorganized Indian territory and for that reason, the 2nd trial wasn’t considered double jeopardy.

Jack McCall was convicted that second time and sentenced to death, his hanging carried out on March 1, 1877. The cemetery was moved nearly five years later. When McCall was exhumed the noose was still tied, around his neck.

You must be logged in to post a comment.