Emil Joseph Kapaun was the son of Czech immigrants, a farm kid who grew up in 1920s Kansas. Graduating from Pilsen High, class of 1930, Kapaun spent much of the 30s in theological seminary, becoming an ordained priest of the Roman Catholic faith on June 9, 1940.

Emil Joseph Kapaun was the son of Czech immigrants, a farm kid who grew up in 1920s Kansas. Graduating from Pilsen High, class of 1930, Kapaun spent much of the 30s in theological seminary, becoming an ordained priest of the Roman Catholic faith on June 9, 1940.

Kapaun served as military chaplain toward the end of WWII, before leaving the army in 1946 and rejoining in 1948.

Chaplain Kapaun was ordered to Korea a month after the North invaded the South, joining the 8th Cavalry Regiment of the 1st Cavalry Division, out of Fort Bliss.

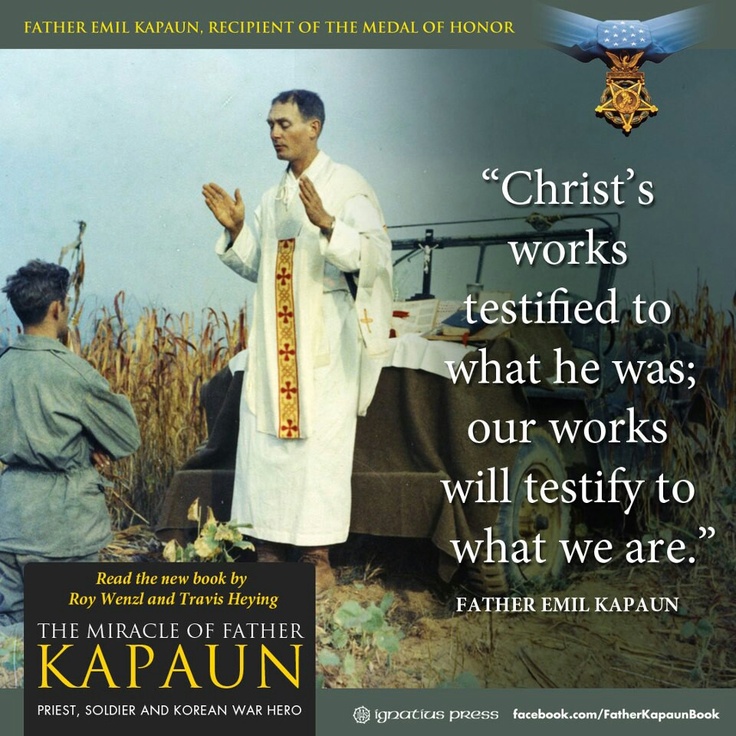

The 8th Cav. entered combat at the Pusan perimeter, moving steadily northward through the summer and fall of 1950. Father Kapaun would minister to the dead and dying, performing baptisms, hearing first confessions and offering holy communion. He would celebrate mass from an improvised altar, set up on the hood of a jeep.

Kapaun once lost his mass kit to enemy fire. He earned a Bronze Star in September that year, running through intense enemy fire to rescue a wounded soldier. His was no rear-echelon ministry.

A single regiment was attacked by the entire 39th Chinese Corps on November 1, and completely overrun the following day. For the US 8th Cavalry, the battle of Unsan was one of the most devastating defeats of the Korean War. Father Kapaun was ordered to evade, an order he deliberately defied. He was performing last rites for a dying soldier, when he was seized by Chinese communist forces.

Prisoners were force marched 87 miles to a Communist POW camp near Pyoktong, in North Korea. Conditions in the camp were gruesome. 1st Lieutenant Michael Dowe was among the prisoners. Through him that we know much of what happened there. Dowe later described Father Kapaun trading his watch for a blanket, only to cut it up to fashion socks for the feet of prisoners.

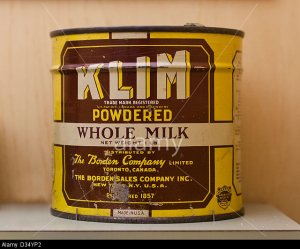

Father Kapaun would risk his life, sneaking into the fields around the prison compound to look for something to eat. He would always bring it back to the communal pot.

Chinese Communist guards would taunt Kapaun, during daily indoctrination sessions, “Where is your god now?” Before and after these sessions, he would move through the camp, ministering to Catholic and non-Catholic alike. Kapaun would slip in behind every work detail, cleaning latrines while other prisoners argued over who’d get the job. He’d wash the filthy laundry of those made weak and incontinent with dysentery.

Starving, suffering from a blood clot in his leg and a severe eye infection, Father Kapaun led Easter services in April, 1951. He was incapacitated a short time later. Guards carried him off to a “hospital”, a fetid, stinking part of the camp known to prisoners as the “death house”, from which few ever returned. “If I don’t come back”, he said, “tell my Bishop that I died a happy death.”

Scores of men credit their survival at Pyoktong, to Chaplain Kapaun.

In the end, Father Kapaun was too weak to lift the plate holding the meager meal his guards left him. US Army records report that he died of pneumonia on May 6, 1951. His fellow POWs will tell you that he died on May 23, of malnutrition and starvation. He was 35.

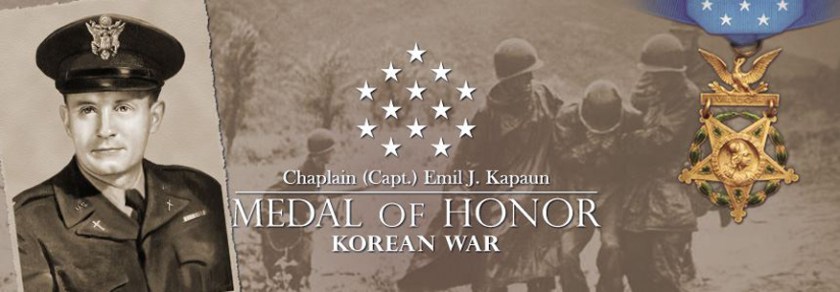

In 2013, President Barack Obama presented Kapaun’s family with a posthumous Medal of Honor for his heroism at Unsan. The New York Times reported that April, “The chaplain “calmly walked through withering enemy fire” and hand-to-hand combat to provide medical aid, comforting words or the last rites of the Roman Catholic Church to the wounded, the citation said. When he saw a Chinese soldier about to execute a wounded comrade, Sgt. First Class Herbert A. Miller, he rushed to push the gun away. Mr. Miller, now 88, was at the White House for the ceremony with other veterans, former prisoners of war and members of the Kapaun family“.

The naming of a Saint of the Roman Catholic church is not a process taken lightly. Pope John Paul II named Father Kapaun a “Servant of God” in 1993, the first step toward Sainthood. On November 9, 2015, the Catholic Diocese of Wichita submitted a 1,066 page report on the life of Chaplain Kapaun, to the Roman Curia at the Vatican.

A team of six historians reviewed the case for beatification. On June 21, 2016, the committee unanimously approved the petition. Two days later, the Wichita Eagle newspaper reported that Father Kapaun was one step closer to sainthood. At the time I write this, Father Emil Joseph Kapaun’s supporters continue working to have him declared a Saint of the Roman Catholic Church, for his lifesaving ministrations at Pyoktong.

The diary tells of a respect this man had for “Captain Boeing”. Beaten almost senseless, his arms tied so tightly that his elbows touched behind his back, Captain Pease was driven to his knees in the last moments of his life. Knowing he was about to die, Harl Pease uttered the most searing insult possible against an expert swordsman and self-styled “samurai”. Particularly one with such a helpless victim. It was the single word, in Japanese. “Once!“.

The diary tells of a respect this man had for “Captain Boeing”. Beaten almost senseless, his arms tied so tightly that his elbows touched behind his back, Captain Pease was driven to his knees in the last moments of his life. Knowing he was about to die, Harl Pease uttered the most searing insult possible against an expert swordsman and self-styled “samurai”. Particularly one with such a helpless victim. It was the single word, in Japanese. “Once!“.

In his spare time, this Green Beret, Army Ranger and Special Forces warrior would volunteer to work in the countless orphanages of South Vietnam.

In his spare time, this Green Beret, Army Ranger and Special Forces warrior would volunteer to work in the countless orphanages of South Vietnam.

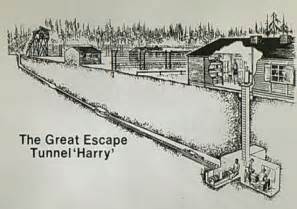

Rocky attempted to escape four times, despite leg wounds which left him no option but to crawl on his belly. Each such attempt earned him savage beatings, after which he’d only try harder.

Rocky attempted to escape four times, despite leg wounds which left him no option but to crawl on his belly. Each such attempt earned him savage beatings, after which he’d only try harder. Rocky was murdered by his captors, his “execution” announced on North Vietnamese “Liberation Radio” on September 26, 1965. He was twenty-eight.

Rocky was murdered by his captors, his “execution” announced on North Vietnamese “Liberation Radio” on September 26, 1965. He was twenty-eight.

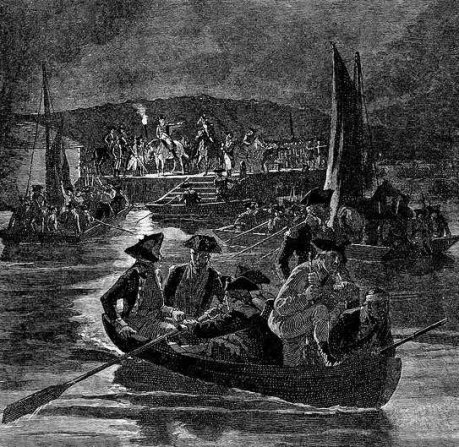

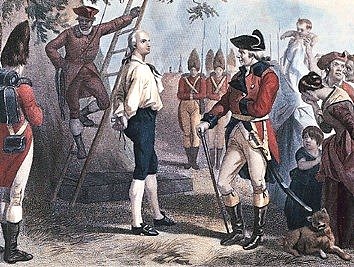

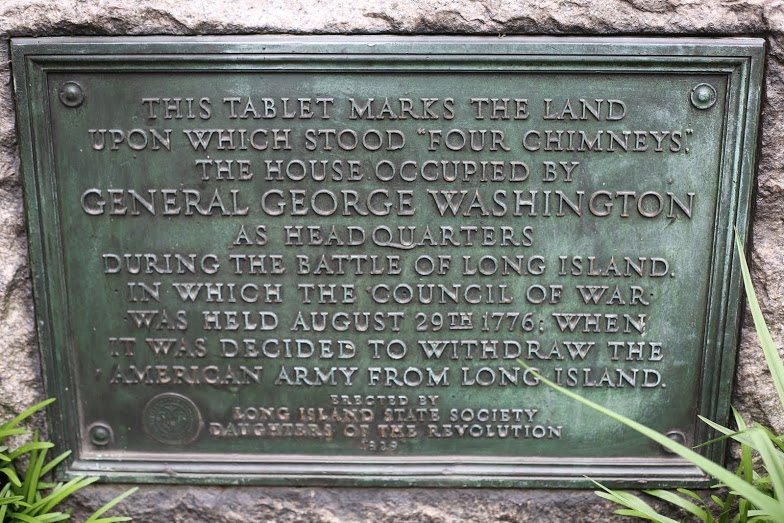

Washington asked for volunteers for a dangerous mission, to go behind enemy lines, as a spy. Up stepped a volunteer. His name was Nathan Hale.

Washington asked for volunteers for a dangerous mission, to go behind enemy lines, as a spy. Up stepped a volunteer. His name was Nathan Hale. Hale took Rogers into his confidence, believing the two to be playing for the same side. Barkhamsted Connecticut shopkeeper Consider Tiffany, a British loyalist and himself a sergeant of the French and Indian War, recorded what happened next, in his journal: “The time being come, Captain Hale repaired to the place agreed on, where he met his pretended friend” (Rogers), “with three or four men of the same stamp, and after being refreshed, began [a]…conversation. But in the height of their conversation, a company of soldiers surrounded the house, and by orders from the commander, seized Captain Hale in an instant. But denying his name, and the business he came upon, he was ordered to New York. But before he was carried far, several persons knew him and called him by name; upon this he was hanged as a spy, some say, without being brought before a court martial.”

Hale took Rogers into his confidence, believing the two to be playing for the same side. Barkhamsted Connecticut shopkeeper Consider Tiffany, a British loyalist and himself a sergeant of the French and Indian War, recorded what happened next, in his journal: “The time being come, Captain Hale repaired to the place agreed on, where he met his pretended friend” (Rogers), “with three or four men of the same stamp, and after being refreshed, began [a]…conversation. But in the height of their conversation, a company of soldiers surrounded the house, and by orders from the commander, seized Captain Hale in an instant. But denying his name, and the business he came upon, he was ordered to New York. But before he was carried far, several persons knew him and called him by name; upon this he was hanged as a spy, some say, without being brought before a court martial.” There is no official account of Nathan Hale’s final words, but we have an eyewitness statement from British Captain John Montresor, who was present at the hanging.

There is no official account of Nathan Hale’s final words, but we have an eyewitness statement from British Captain John Montresor, who was present at the hanging.

Hess was an early and ardent proponent of Nazi ideology. A True Believer. He was at Hitler’s side during the failed revolution of 1923, the “Beer Hall Putsch”. He served time with Hitler in prison, and helped him write his political opus “Mein Kampf” (My Struggle). Hess was appointed to Hitler’s cabinet when the National Socialist German Workers’ Party seized power in 1933, becoming Deputy Führer, #3 after Hermann Göring and Hitler himself. Hess signed many statutes into law, including the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, depriving the Jews of Germany of their rights and property.

Hess was an early and ardent proponent of Nazi ideology. A True Believer. He was at Hitler’s side during the failed revolution of 1923, the “Beer Hall Putsch”. He served time with Hitler in prison, and helped him write his political opus “Mein Kampf” (My Struggle). Hess was appointed to Hitler’s cabinet when the National Socialist German Workers’ Party seized power in 1933, becoming Deputy Führer, #3 after Hermann Göring and Hitler himself. Hess signed many statutes into law, including the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, depriving the Jews of Germany of their rights and property.

Exhausted, sunburned and aching with thirst, Tonelli still refused when a Japanese soldier demanded his Notre Dame class ring. As the guard reached for his sword, a nearby prisoner shouted “Give it to him. It’s not worth dying for”.

Exhausted, sunburned and aching with thirst, Tonelli still refused when a Japanese soldier demanded his Notre Dame class ring. As the guard reached for his sword, a nearby prisoner shouted “Give it to him. It’s not worth dying for”. The hellish 60-day journey aboard the filthy, cramped merchant vessel began in late 1944, destined for slave labor camps in mainland Japan. Tonelli was barely 100 pounds on arrival, his body ravaged by malaria and intestinal parasites. He was barely half the man who once played fullback at Notre Dame Stadium, Soldier Field and Comiskey Park.

The hellish 60-day journey aboard the filthy, cramped merchant vessel began in late 1944, destined for slave labor camps in mainland Japan. Tonelli was barely 100 pounds on arrival, his body ravaged by malaria and intestinal parasites. He was barely half the man who once played fullback at Notre Dame Stadium, Soldier Field and Comiskey Park.

You must be logged in to post a comment.