Europe was embarked on yet another of its depressingly regular paroxysms of anti-Semitism in the late 19th century, when Alfred Dreyfus was arrested for espionage.

A French Captain of Jewish-Alsatian background, the “evidence” against him was almost non-existent, limited to an on-the-spot handwriting analysis of a tissue paper missive written to the German Embassy. “Expert” testimony came from Alphonse Bertillon, inventor of the modern ‘mug shot’ and an enthusiastic proponent of anthropometry in law enforcement, the collection of body measurements and proportions for purposes of identification, later phased out by the use of fingerprints. Though no handwriting expert, Bertillon opined that Dreyfus’ handwriting was similar to that of the sample, explaining the differences with a cockamamie theory he called “autoforgery”.

Chief Inspector Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Armand Auguste Ferdinand Mercier du Paty de Clam, himself no handwriting expert, agreed with Bertillon. With no file and only the flimsiest of evidence, de Clam summoned Dreyfus for interrogation on October 13, 1894. Dreyfus maintained his innocence during the interrogation, with his inquisitor going so far as to slide a revolver across the table, silently suggesting that Dreyfus kill himself. Du Paty arrested Dreyfus two days later, informing the captain that he would be brought before a Court Martial.

Despite the paucity of evidence, the young artillery officer was convicted of handing over State Secrets in November 1894. The insignia was torn from his uniform and his sword broken, and then he was paraded before a crowd that shouted, “Death to Judas, death to the Jew.” Dreyfus was sentenced to life, and sent to the penal colony at Devil’s Island in French Guiana, where he spent almost five years.

A simple miscarriage of justice elevated to a national scandal two years later, when evidence came to light identifying French Army major Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy as the real culprit. Esterhazy was brought to trial in 1896, but high ranking military officials suppressed evidence, and he was acquitted on the second day of trial. The military dug in, accusing Dreyfus of additional crimes based on false documents. Indignation at the obvious frame-up began to spread.

Most of the political and military establishment lined up against Dreyfus, but the public outcry became furious after writer Émile Zola published his vehement open letter “J’accuse” (I accuse) in the Paris press in January 1898.

Most of the political and military establishment lined up against Dreyfus, but the public outcry became furious after writer Émile Zola published his vehement open letter “J’accuse” (I accuse) in the Paris press in January 1898.

Zola himself was tried and convicted for libel, and fled to England.

Liberal and academic activists put pressure on the government to reopen the case. On June 5 1899, Alfred Dreyfus learned of the Supreme Court decision to revisit the judgment of 1894, and to return him to France for a new trial.

What followed nearly tore the country apart. “Dreyfusards” such as Anatole France, Henri Poincaré and future Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau were pitted against anti-Dreyfusards such as Edouard Drumont, publisher of the anti-Semitic newspaper La Libre Parole. To his supporters, the “Dreyfus affair” was a grotesque miscarriage of justice. A clear and obvious frame-up. To his detractors, Dreyfus came to symbolize the supposed disloyalty of French Jews, the attempt to reopen the case an attack on the nation and an attempt to weaken the army in order to place it under parliamentary control.

The new trial was a circus. The political and military establishments stonewalled. One of Dreyfus’ two attorneys was shot in the back on the way to court. The judge dismissed Esterhazy’s testimony, even though the man had confessed to the crime by that time. The new trial resulted in another conviction, this time with a ten-year sentence. Dreyfus would probably not have survived another 10 years in the Guiana penal colony. This time, he was pardoned and set free.

Alfred Dreyfus was finally exonerated of all charges in 1906, and reinstated as a Major in the French Army, where he served with honor for the duration of World War I, honorably ending his service at the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel.

The Dreyfus affair has been called “a modern and universal symbol of injustice”. The divisions and animosities left in the world of French politics, would remain for years. The French army would not publicly declare the man’s innocence, until 1995.

As the story goes, it was 1853, at an upscale resort in Saratoga Springs New York. A wealthy and somewhat unpleasant customer sent his fried potatoes back to the kitchen, complaining that they were too soggy, and they didn’t have enough salt. George Crum, back in the kitchen, doesn’t seem to have been a very nice guy, himself. Crum thought he’d fix this guy, so he sliced some potatoes wafer-thin, fried them up and doused the hell out of them, with salt. Sending them out to the table and fully expecting the customer to choke on them, Crum was astonished to learn that the guy loved them. He ordered more, and George Crum decided to add “Saratoga Chips” to the menu. The potato chip was born.

As the story goes, it was 1853, at an upscale resort in Saratoga Springs New York. A wealthy and somewhat unpleasant customer sent his fried potatoes back to the kitchen, complaining that they were too soggy, and they didn’t have enough salt. George Crum, back in the kitchen, doesn’t seem to have been a very nice guy, himself. Crum thought he’d fix this guy, so he sliced some potatoes wafer-thin, fried them up and doused the hell out of them, with salt. Sending them out to the table and fully expecting the customer to choke on them, Crum was astonished to learn that the guy loved them. He ordered more, and George Crum decided to add “Saratoga Chips” to the menu. The potato chip was born.

Lay began buying up small regional competitors at the same time that another company specializing in corn chips was doing the same. “Frito”, the Spanish word for “fried”, merged with Lay in 1961 to become – you got it – Frito-Lay. By 1965, the year Frito-Lay merged with Pepsi-Cola to become PepsiCo, Lay’s was the #1 potato chip brand in every state in America.

Lay began buying up small regional competitors at the same time that another company specializing in corn chips was doing the same. “Frito”, the Spanish word for “fried”, merged with Lay in 1961 to become – you got it – Frito-Lay. By 1965, the year Frito-Lay merged with Pepsi-Cola to become PepsiCo, Lay’s was the #1 potato chip brand in every state in America.

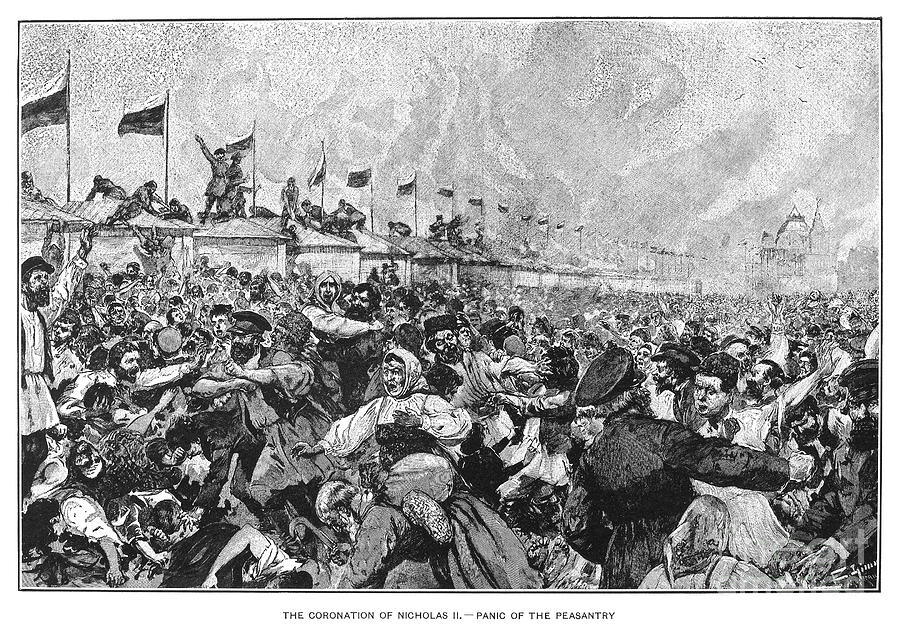

People began to gather on the 29th. By 5:00am on the 30th, the crowd was estimated at half a million. A rumor began to spread among the crowd that there wasn’t enough beer or pretzels to go around. At that point the police force of 1,800 wasn’t enough to maintain order. The crush of the crowd and the resulting panic resulted in a human stampede. Before it was over 1,389 people were trampled to death, and another 1,300 injured.

People began to gather on the 29th. By 5:00am on the 30th, the crowd was estimated at half a million. A rumor began to spread among the crowd that there wasn’t enough beer or pretzels to go around. At that point the police force of 1,800 wasn’t enough to maintain order. The crush of the crowd and the resulting panic resulted in a human stampede. Before it was over 1,389 people were trampled to death, and another 1,300 injured.

In 1726, Quaker minister John Wright began a “ferry” service across the Susquehanna River. Starting as a pair of dugout canoes, “Pennsylvania Dutch” farmers were soon settling the Conejohela Valley on the eastern border of Maryland and Pennsylvania.

In 1726, Quaker minister John Wright began a “ferry” service across the Susquehanna River. Starting as a pair of dugout canoes, “Pennsylvania Dutch” farmers were soon settling the Conejohela Valley on the eastern border of Maryland and Pennsylvania.

The bizarre and hideous acts of cruelty that Mengele performed in the name of “science” are beyond the scope of this essay, but seven dwarves didn’t come along every day. The Angel of Death treated the Ovitz siblings differently than other camp inmates.

The bizarre and hideous acts of cruelty that Mengele performed in the name of “science” are beyond the scope of this essay, but seven dwarves didn’t come along every day. The Angel of Death treated the Ovitz siblings differently than other camp inmates.

Roddenberry decided on James T. Kirk, based on a journal entry of the 18th century British explorer, Captain James Cook: “ambition leads me … farther than any other man has been before me”.

Roddenberry decided on James T. Kirk, based on a journal entry of the 18th century British explorer, Captain James Cook: “ambition leads me … farther than any other man has been before me”.

Dorothy Eustis called Frank in February 1928 and asked if he was willing to come to Switzerland. The response left little doubt: “Mrs. Eustis, to get my independence back, I’d go to hell”. She accepted the challenge and trained two dogs, leaving it to Frank to decide which was the more suitable. Morris came to Switzerland to work with the dogs, both female German Shepherds. He chose one named “Kiss” but, feeling that no 20-year-old man should have a dog named Kiss, he called her “Buddy”.

Dorothy Eustis called Frank in February 1928 and asked if he was willing to come to Switzerland. The response left little doubt: “Mrs. Eustis, to get my independence back, I’d go to hell”. She accepted the challenge and trained two dogs, leaving it to Frank to decide which was the more suitable. Morris came to Switzerland to work with the dogs, both female German Shepherds. He chose one named “Kiss” but, feeling that no 20-year-old man should have a dog named Kiss, he called her “Buddy”.

Frank told a New York Times interviewer in 1936 that he had probably logged 50,000 miles with Buddy, by foot, train, subway, bus, and boat. He was constantly meeting with people, including two Presidents and over 300 ophthalmologists, demonstrating the life-changing qualities of owning a guide dog.

Frank told a New York Times interviewer in 1936 that he had probably logged 50,000 miles with Buddy, by foot, train, subway, bus, and boat. He was constantly meeting with people, including two Presidents and over 300 ophthalmologists, demonstrating the life-changing qualities of owning a guide dog.

Queen Elizabeth I of England granted Walter Raleigh a charter to establish a colony north of Spanish Florida in 1583, the area called “Virginia”, in honor of the virgin Queen. At the time, the name applied to the entire coastal region from South Carolina to Maine, and included Bermuda.

Queen Elizabeth I of England granted Walter Raleigh a charter to establish a colony north of Spanish Florida in 1583, the area called “Virginia”, in honor of the virgin Queen. At the time, the name applied to the entire coastal region from South Carolina to Maine, and included Bermuda.

Sandwich established in 1637, followed by Barnstable and Yarmouth in 1639. The thin soil was ill suited to agriculture, and intensive farming techniques eroded topsoil. Farmers grazed cattle on the grassy dunes of the shoreline, only to watch “in horror as the denuded sands ‘walked’ over richer lands, burying cultivated fields and fences.”

Sandwich established in 1637, followed by Barnstable and Yarmouth in 1639. The thin soil was ill suited to agriculture, and intensive farming techniques eroded topsoil. Farmers grazed cattle on the grassy dunes of the shoreline, only to watch “in horror as the denuded sands ‘walked’ over richer lands, burying cultivated fields and fences.”

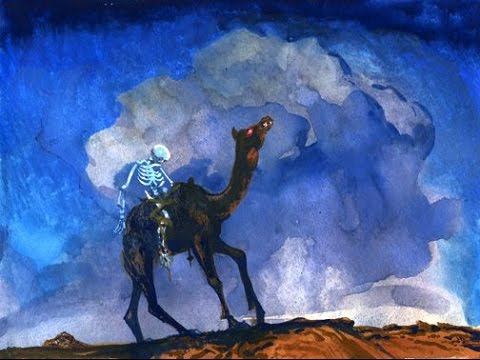

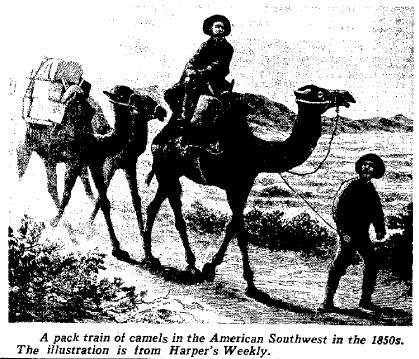

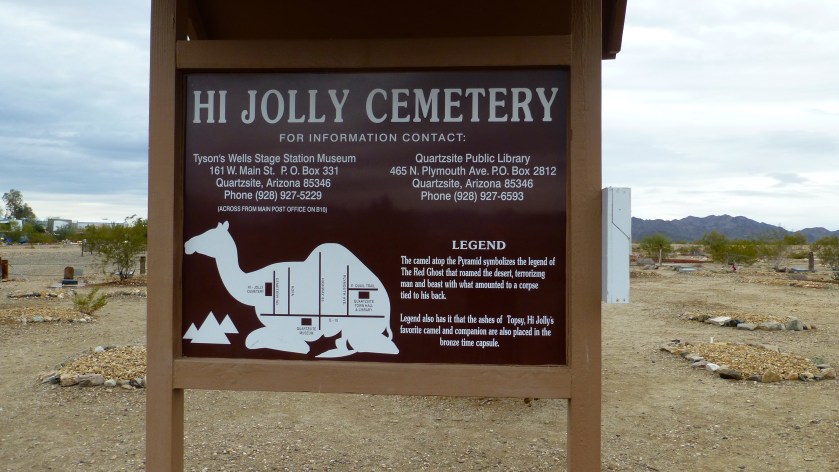

Some of Camp Verde’s camels were sold off, one was pushed over a cliff by frustrated cavalrymen. Most were simply turned loose to fend for themselves. Their fates are mostly unknown, except for one who made his way to Mississippi in 1863, where he was taken into service with the 43rd Infantry Regiment. “Douglas the Confederate Camel” was a common sight throughout the siege of Vicksburg, until being shot and killed by a Union sharpshooter. Lieutenant Colonel Robert Bevier of the 5th Regiment, Missouri Confederate Infantry was furious, enlisting six of his best snipers to rain down hell on Douglas’ killer. Bevier later said of the Federal soldier “I refused to hear his name, and was rejoiced to learn that he had been severely wounded.”

Some of Camp Verde’s camels were sold off, one was pushed over a cliff by frustrated cavalrymen. Most were simply turned loose to fend for themselves. Their fates are mostly unknown, except for one who made his way to Mississippi in 1863, where he was taken into service with the 43rd Infantry Regiment. “Douglas the Confederate Camel” was a common sight throughout the siege of Vicksburg, until being shot and killed by a Union sharpshooter. Lieutenant Colonel Robert Bevier of the 5th Regiment, Missouri Confederate Infantry was furious, enlisting six of his best snipers to rain down hell on Douglas’ killer. Bevier later said of the Federal soldier “I refused to hear his name, and was rejoiced to learn that he had been severely wounded.” men to return. The pair returned that night and found the body of the other woman by the stream. She’d been trampled almost flat, with huge, cloven hoof prints in the mud around her body and a few red hairs in the brush.

men to return. The pair returned that night and found the body of the other woman by the stream. She’d been trampled almost flat, with huge, cloven hoof prints in the mud around her body and a few red hairs in the brush. There were further incidents over the next year, mostly at prospector camps. A cowboy near Phoenix came upon the Red Ghost while eating grass in a corral. Cowboys seem to think they can rope anything with hair on it, and this guy was no exception. He lashed the rope onto the pommel of his saddle, and tossed it over the camel’s head. The angry beast turned and charged, knocking horse and rider to the ground. As the camel galloped off, the astonished cowboy could clearly see the skeletal remains of a man lashed to its back.

There were further incidents over the next year, mostly at prospector camps. A cowboy near Phoenix came upon the Red Ghost while eating grass in a corral. Cowboys seem to think they can rope anything with hair on it, and this guy was no exception. He lashed the rope onto the pommel of his saddle, and tossed it over the camel’s head. The angry beast turned and charged, knocking horse and rider to the ground. As the camel galloped off, the astonished cowboy could clearly see the skeletal remains of a man lashed to its back.

The group reunited in 1974 to do the Holy Grail, which was filmed on location in Scotland, on a budget of £229,000. The money was raised in part by investments from musical figures like Pink Floyd, Jethro Tull and Led Zeppelin backer Tony Stratton-Smith. Investors in the film wanted to cut the famous Black Knight scene, (“None shall pass”), but were eventually persuaded to keep it in the film. Good thing, the scene became second only to the Holy Hand Grenade of Antioch and the Killer Rabbit. “What’s he going to do, nibble my bum?”

The group reunited in 1974 to do the Holy Grail, which was filmed on location in Scotland, on a budget of £229,000. The money was raised in part by investments from musical figures like Pink Floyd, Jethro Tull and Led Zeppelin backer Tony Stratton-Smith. Investors in the film wanted to cut the famous Black Knight scene, (“None shall pass”), but were eventually persuaded to keep it in the film. Good thing, the scene became second only to the Holy Hand Grenade of Antioch and the Killer Rabbit. “What’s he going to do, nibble my bum?”

You must be logged in to post a comment.