The June 28, 1914 assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand began a cascade of events which would change the course of the 20th century. Entangling alliances and mutual suspicion combined with slavish dependence on timetables to effect the mobilization and counter-mobilization of armies.

Remember the 1960s counterculture slogan “what if there was a war and nobody came”? In 1914, no one wanted to show up late in the event of war. And so, there was war. By October, the “War to End All Wars” had ground down to the trench-bound hell which would characterize the next four years.

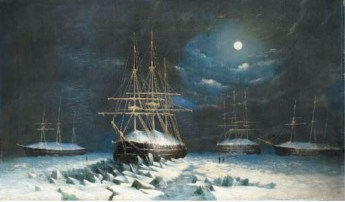

Both the German and British economies were heavily dependent on imports to feed populations at home and to prosecute the war effort. By February 1915, the two powers were attempting to throttle the other through naval blockade.

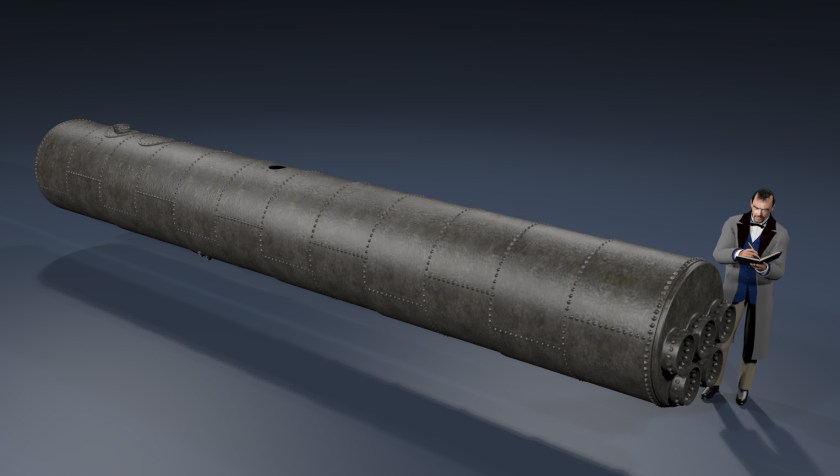

Great Britain’s Royal Navy had superior numbers, while the Imperial German Naval surface fleet was restricted to an area of the North Sea called the German Bight. In other theaters, Germans augmented their small navy with commerce raiders and “unterseeboots”. More than any other cause it was the German policy of unrestricted submarine warfare which would bring the United States into the war, two years later.

On February 4, 1915, Imperial Germany declared a naval blockade against shipping to Britain stating that “On and after February 18th every enemy merchant vessel found in this region will be destroyed, without its always being possible to warn the crews or passengers of the dangers threatening”. “Neutral ships” the statement continued, “will also incur danger in the war region”.

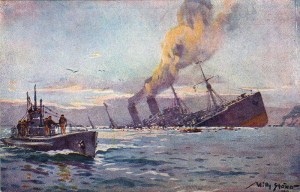

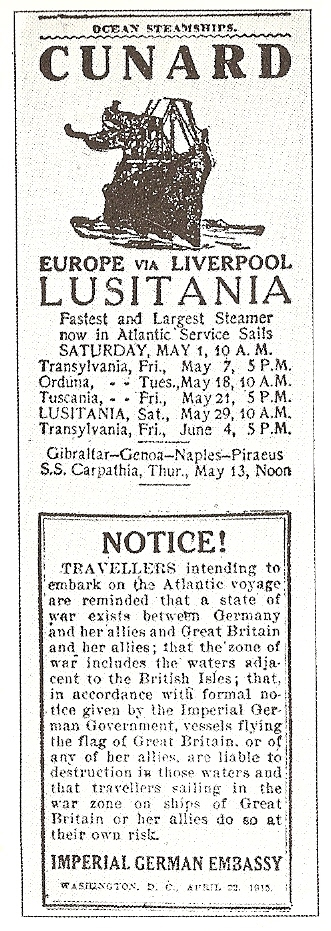

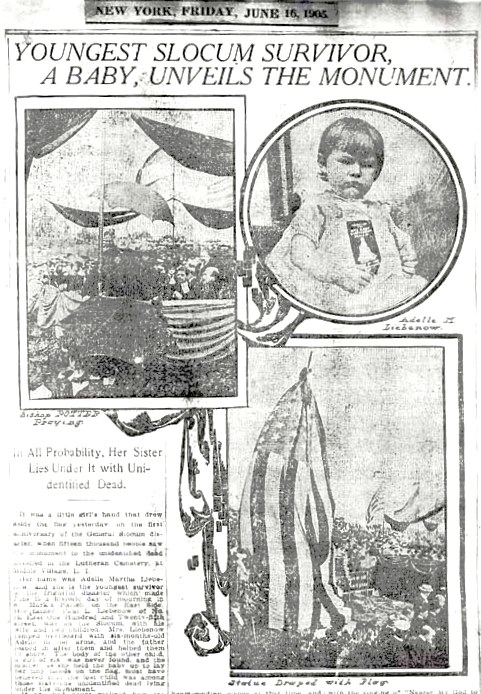

As the war unfolded, German U-boats sank nearly 5,000 ships, close to 13 million gross register ton including the Cunard Liner Lusitania, torpedoed and sunk off Kinsale, Ireland on May 7, 1915. 1,198 were drowned including 128 Americans. 100 of the dead, were children.

Reaction in the United States and the United Kingdom alike were immediate, and vehement. The sinking was portrayed as the act of barbarians and Huns. For their part the Imperial German government maintained that Lusitania was illegally transporting munitions intended to kill German boys on European battlefields. Furthermore, as the embassy pointed out ads were taken out in the New York Times and other newspapers specifically warning that the liner was subject to attack.

Warnings from the German embassy often ran directly opposite ads for the sailing itself. Many dismissed such warnings believing such an attack, was unlikely.

Unrestricted submarine warfare was suspended for a time, for fear of bringing the US into the war. The policy was reinstated in January 1917 prompting then-Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg to comment, “Germany is finished”. He was right.

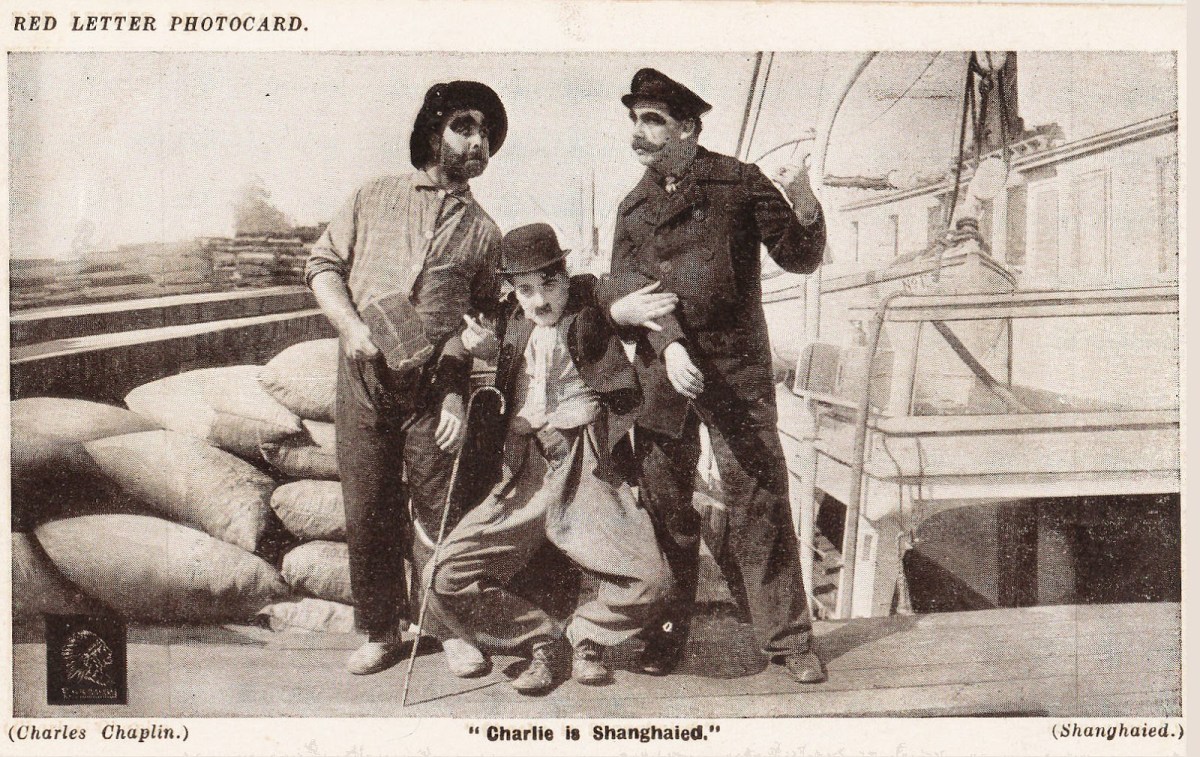

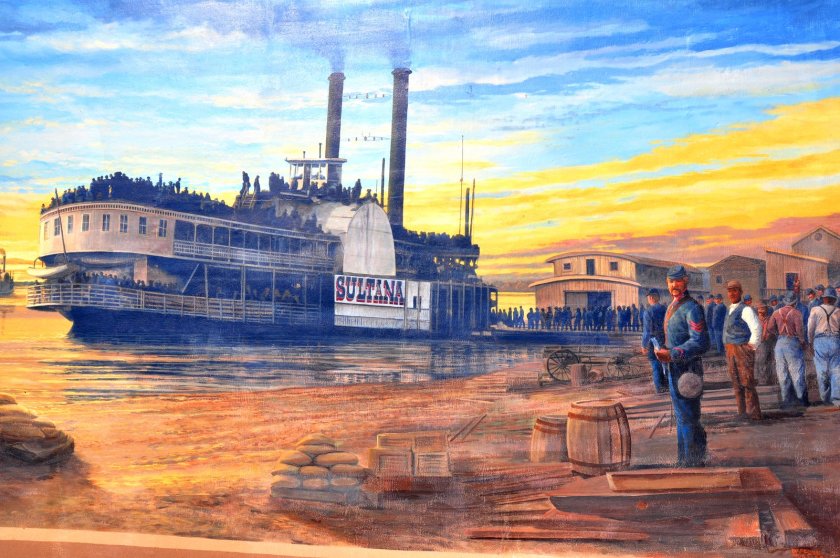

On February 3, 1917, SS Housatonic was enroute from Galveston Texas to Liverpool England bearing a cargo of flour, and grain. Passing the southwest coast of England the liner was stopped and boarded by the German submarine U-53.

American Captain Thomas Ensor was interviewed by Kapitänleutnant Hans Rose, who said he was sorry. Housatonic he said, was “carrying food supplies to the enemy of my country”, and would be destroyed. The American Captain and crew were allowed to launch lifeboats and abandon ship while German sailors raided the American vessel .

Based on what was taken, WWI vintage German subs were especially short on soap.

Abandoned and adrift Housatonic was sunk with a single torpedo, U-53 towing the now-stranded Americans toward the English coast. Sighting the trawler Salvator, Rose fired his deck guns to be sure they’d been seen, and then slipped away.

President Woodrow Wilson retaliated, breaking off diplomatic relations with Germany the same day. Four days later a German U-boat fired two torpedoes at the SS California, off the Irish coast. One missed but the second tore into the port side of the 470-foot, 9,000-ton steamer. California sank in nine minutes killing 43 of her 205 passengers and crew.

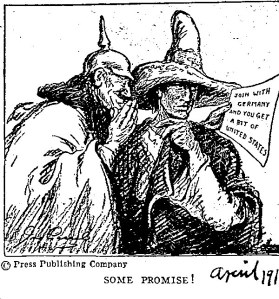

Two weeks later, British Intelligence divulged the Zimmermann note to Edward Bell, secretary to the United States Embassy in Britain. It was a diplomatic overture from German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmermann to the Mexican government, promising American territories in exchange for a Mexican declaration of war against the United States.

Zimmermann’s note read, in part:

“We intend to begin on the first of February unrestricted submarine warfare. We shall endeavor in spite of this to keep the United States of America neutral. In the event of this not succeeding, we make Mexico a proposal of alliance on the following basis: make war together, make peace together, generous financial support and an understanding on our part that Mexico is to reconquer the lost territory in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona…”

In the United States, the political tide was turning. Unrestricted submarine warfare…the Housatonic…the California and now the Zimmermann telegram…the events combined to become the last straw. On April 2 the President who had won re-election on the slogan “He kept us out of war” addressed a joint session of the United States Congress, requesting a declaration of war.

At the time, the German claim that Lusitania carried contraband munitions seemed to be supported by survivors’ reports of secondary explosions within the stricken liner’s hull. In 2008, the UK Daily Mail reported that dive teams had reached the wreck, lying at a depth of 300′. Divers reported finding tons of US manufactured Remington .303 ammunition, about 4 million rounds, stored in unrefrigerated cargo holds in cases marked “Cheese”, “Butter”, and “Oysters”.

You must be logged in to post a comment.