In the early 1930s, Mary Elizabeth Frye was a Baltimore housewife and amateur florist, the wife of clothing merchant, Claud Frye.

A young Jewish girl was living with the couple at this time, unable to visit her sick mother in Germany, due to the growing anti-Semitic violence of the period. Her name was Margaret Schwarzkopf.

Margaret was bereft when her mother died, heartbroken that she could never “stand by my mother’s grave and shed a tear.” Mrs Frye took up a brown paper shopping bag, and wrote out this twelve line verse.

She didn’t title the poem, nor did she ever publish it, nor copyright the work. People heard about it and liked it so Frye would make copies, but that’s about it.

For nigh on seventy years, few knew from where this little known bit of verse, had come.

Over the years, there have been many claims to authorship, including attributions to traditional and Native American origins.

The unknown poem has been translated into Danish, Dutch, French, German, Hebrew, Ilocano, Japanese, Korean, Russian, Spanish, Tagalog and other languages, appearing on countless bereavement cards and read over untold funeral services.

The English translation of one Swedish version reads: “Do not weep at my grave – I am not there / I am in the sun’s reflection in the sea / I am in the wind’s play above the grain fields / I am in the autumn’s gentle rain / I am in the Milky Way’s string of stars / And when on an early morning you are awaked by bird’s song / It is my voice that you are hearing / So do not weep at my grave – we shall meet again.”

Many in the United Kingdom heard the poem for the first time in 1995, when a grieving father read it over BBC radio in honor of his son, a soldier slain by a bomb in Northern Ireland. The son had left the poem with a few personal effects, and marked the envelope ‘To all my loved ones’.

For National Poetry Day that year, the British television program The Bookworm conducted a poll to learn the nation’s favorite poems, subsequently publishing the winners, in book form. The book’s preface describes “Do Not Stand at My Grave and Weep” as “the unexpected poetry success of the year from Bookworm’s point of view… the requests started coming in almost immediately and over the following weeks the demand rose to a total of some thirty thousand. In some respects it became the nation’s favourite poem by proxy… despite it being outside the competition.”

All this at a time when the name and even the nationality of the author, was unknown.

Abigail Van Buren, better known as “Dear Abby”, researched the history of the poem in 1998, and determined that Mrs. Frye was, after all, the author.

Mary Elizabeth Frye passed away in Baltimore Maryland on September 4, 2004. She was ninety-eight.

The Times of Great Britain published her untitled work on November 5, as part of her obituary. ‘The verse demonstrated a remarkable power to soothe loss”, wrote the Times. “It became popular, crossing national boundaries for use on bereavement cards and at funerals regardless of race, religion or social status”.

“I Did Not Die”

by Mary Elizabeth Frye

Do not stand at my grave and weep,

I am not there; I do not sleep.

I am a thousand winds that blow,

I am the diamond glints on snow,

I am the sun on ripened grain,

I am the gentle autumn rain.

When you awaken in the morning’s hush

I am the swift uplifting rush

Of quiet birds in circling flight.

I am the soft star-shine at night.

Do not stand at my grave and cry,

I am not there; I did not die.

The information was surprisingly difficult to find, and no reference book was available to settle the matter.

The information was surprisingly difficult to find, and no reference book was available to settle the matter.

The free reference book once intended to inform barroom squabbles has spawned a franchise including museums and television programs, becoming the leading international authority for the certification of every world record you can think of, from the longest fingernail (2 feet, 11 inches), to the longest mustache (14 feet), to slam dunking basketball bunnies.

The free reference book once intended to inform barroom squabbles has spawned a franchise including museums and television programs, becoming the leading international authority for the certification of every world record you can think of, from the longest fingernail (2 feet, 11 inches), to the longest mustache (14 feet), to slam dunking basketball bunnies.

Field Marshall Helmuth von Moltke once said “No battle plan ever survives contact with the enemy”. So it was in the tiny Belgian city where German plans met with ruin, on the road to Dunkirk. Native Dutch speakers called the place Leper. Today we know it as Ypres (Ee-pres), since battle maps of the time were drawn up in French. To the Tommys of the British Expeditionary Force, the place was “Wipers”.

Field Marshall Helmuth von Moltke once said “No battle plan ever survives contact with the enemy”. So it was in the tiny Belgian city where German plans met with ruin, on the road to Dunkirk. Native Dutch speakers called the place Leper. Today we know it as Ypres (Ee-pres), since battle maps of the time were drawn up in French. To the Tommys of the British Expeditionary Force, the place was “Wipers”. The second Battle for Ypres began with a new and terrifying weapon on April 22, 1915. German troops placed 5,730 gas cylinders weighing 90 pounds apiece, along a four-mile front. Allied troops must have looked on in wonder, as that vast yellow-green carpet crept toward their lines.

The second Battle for Ypres began with a new and terrifying weapon on April 22, 1915. German troops placed 5,730 gas cylinders weighing 90 pounds apiece, along a four-mile front. Allied troops must have looked on in wonder, as that vast yellow-green carpet crept toward their lines.

Units of all sizes, from individual companies to army corps, lightened the load of the “War to end all Wars”, with some kind of unit journal.

Units of all sizes, from individual companies to army corps, lightened the load of the “War to end all Wars”, with some kind of unit journal.

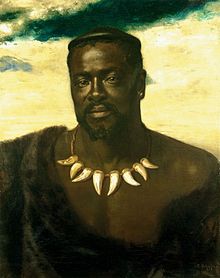

Forty years later and half a world away, what would one day become South Africa was divided into four entities: the two British possessions of Cape Colony and Natal, and the two Boer (Dutch) Republics of the Orange Free State and the South African Republic, better known as Transvaal. Of the four states, Natal and the two Boer Republics were mainly agricultural, populated by subsistence farmers. The Cape Colony was by far the largest, dominating the other three economically, culturally, and socially.

Forty years later and half a world away, what would one day become South Africa was divided into four entities: the two British possessions of Cape Colony and Natal, and the two Boer (Dutch) Republics of the Orange Free State and the South African Republic, better known as Transvaal. Of the four states, Natal and the two Boer Republics were mainly agricultural, populated by subsistence farmers. The Cape Colony was by far the largest, dominating the other three economically, culturally, and socially.

In February, Dickens took a train north to the factory town of Lowell, visiting the textile mills and speaking with the “mill girls”, the women who worked there. Once again, he seemed to believe that his native England suffered in the comparison. Dickens spoke of the new buildings and the well dressed, healthy young women who worked in them, no doubt comparing them with the teeming slums and degraded conditions in London.

In February, Dickens took a train north to the factory town of Lowell, visiting the textile mills and speaking with the “mill girls”, the women who worked there. Once again, he seemed to believe that his native England suffered in the comparison. Dickens spoke of the new buildings and the well dressed, healthy young women who worked in them, no doubt comparing them with the teeming slums and degraded conditions in London. Dickens left with a copy of “The Lowell Offering”, a literary magazine written by those same mill girls, which he later described as “four hundred good solid pages, which I have read from beginning to end.”

Dickens left with a copy of “The Lowell Offering”, a literary magazine written by those same mill girls, which he later described as “four hundred good solid pages, which I have read from beginning to end.” The research which followed was published in the form of a thesis, later fleshed out to a full-length book:

The research which followed was published in the form of a thesis, later fleshed out to a full-length book:

The fifteenth child of Josiah and Abiah Franklin was born in a little house on Milk Street, across from the Old South Church, in Boston.

The fifteenth child of Josiah and Abiah Franklin was born in a little house on Milk Street, across from the Old South Church, in Boston.

James Franklin and his literary friends loved the letters, and published every one. All of Boston was charmed with Silence Dogood’s subtle mockery of the city’s Old School Puritan elite. Proposals of marriage came into the print shop, when the widow Dogood coyly suggested that she would welcome suitors.

James Franklin and his literary friends loved the letters, and published every one. All of Boston was charmed with Silence Dogood’s subtle mockery of the city’s Old School Puritan elite. Proposals of marriage came into the print shop, when the widow Dogood coyly suggested that she would welcome suitors. All of Boston was amused by the hoax, but not James. He was furious with his little brother, who soon broke the terms of his apprenticeship and fled to Pennsylvania.

All of Boston was amused by the hoax, but not James. He was furious with his little brother, who soon broke the terms of his apprenticeship and fled to Pennsylvania. Franklin’s diplomacy to the Court of Versailles was every bit as important to the success of the Revolution, as the Generalship of the Father of the Republic, George Washington. Signatory to both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, it is arguably Ben Franklin who broke the impasse of the Convention of 1787, paving the way for ratification of the United States Constitution.

Franklin’s diplomacy to the Court of Versailles was every bit as important to the success of the Revolution, as the Generalship of the Father of the Republic, George Washington. Signatory to both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, it is arguably Ben Franklin who broke the impasse of the Convention of 1787, paving the way for ratification of the United States Constitution.

In 2003, author Richard Rubin set out to interview the last surviving veterans of World War One. The people he sought were over 101, one was 113.

In 2003, author Richard Rubin set out to interview the last surviving veterans of World War One. The people he sought were over 101, one was 113.

Frank Woodruff Buckles, born Wood Buckles, is one of them. Born on this day in 1901, Buckles joined the Ambulance Corps of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) at the age of 16. He never saw combat against the Germans, but he would escort 650 of them back home as prisoners.

Frank Woodruff Buckles, born Wood Buckles, is one of them. Born on this day in 1901, Buckles joined the Ambulance Corps of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) at the age of 16. He never saw combat against the Germans, but he would escort 650 of them back home as prisoners.

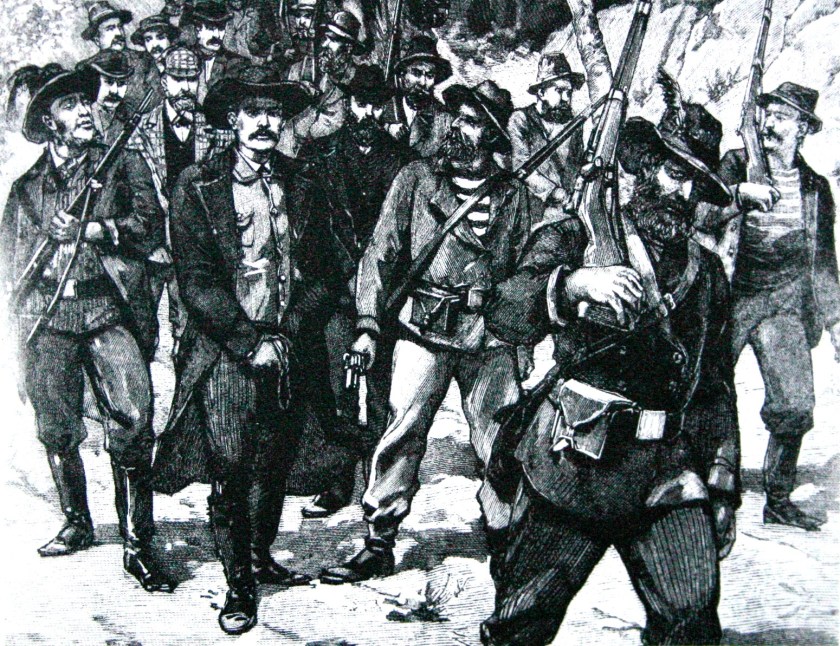

the raiders entered Pretoria on January 2, in chains. The Transvaal government received almost £1 million compensation from the British South Africa Company, turning their prisoners over to be tried by the British government. Jameson was convicted of leading the raid and sentenced to 15 months in prison. During the whole ordeal, he never revealed the degree to which British politicians supported the raid, or the way they betrayed him in the end.

the raiders entered Pretoria on January 2, in chains. The Transvaal government received almost £1 million compensation from the British South Africa Company, turning their prisoners over to be tried by the British government. Jameson was convicted of leading the raid and sentenced to 15 months in prison. During the whole ordeal, he never revealed the degree to which British politicians supported the raid, or the way they betrayed him in the end.

You must be logged in to post a comment.