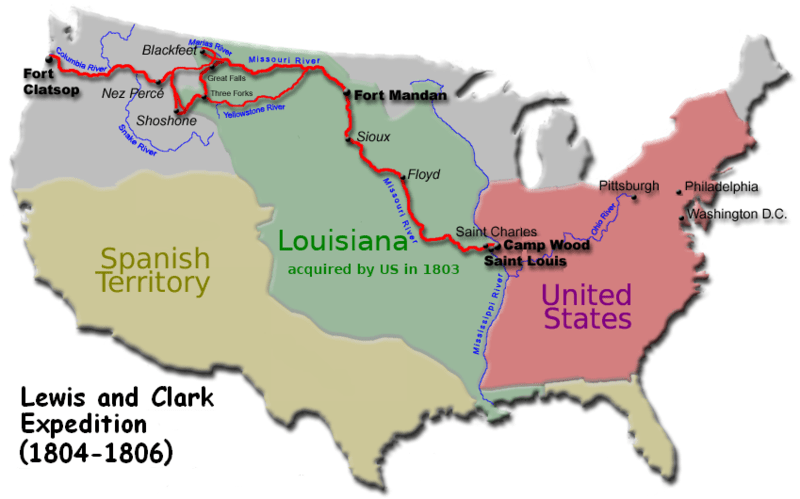

Since the time of Columbus, European explorers searched for a navigable shortcut by open water, from Europe to Asia. The “Corps of Discovery“, better known as the Lewis and Clark expedition, departed the Indiana Territory in 1804 with, among other purposes, and intention of finding a water route to the Pacific.

Forty years later, Captain sir John Franklin departed England aboard two ships, HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, to discover the mythical Northwest Passage.

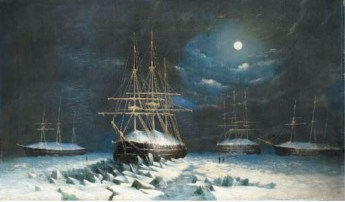

The two ships became icebound in Victoria Strait near King William Island, in the Canadian Arctic.

Prodded by Lady Jane Franklin, the hunt for her husband’s expedition would continue for years, at one time involving as any as eleven British and two American ships. Clues were found including notes and isolated graves, telling the story of a long and fruitless effort to stay alive in a hostile climate. The wreck of HMS Erebus would not be discovered until 2014, her sister ship, two years later.

In 1848, the British Admiralty possessed few ships suitable for arctic service. Two civilian steamships were purchased and converted to exploration vessels: HMS Pioneer and HMS Intrepid, along with four seagoing sailing vessels, Resolute, Assistance, Enterprise and Investigator.

HMS Resolute was a Barque rigged merchant ship, purchased in 1850 as the Ptarmigan, and refitted for Arctic exploration. Re-named Resolute, the vessel became part of a five ship squadron leaving England in April 1852, sailing into the Canadian arctic in search of the doomed Franklin expedition.

HMS Resolute was a Barque rigged merchant ship, purchased in 1850 as the Ptarmigan, and refitted for Arctic exploration. Re-named Resolute, the vessel became part of a five ship squadron leaving England in April 1852, sailing into the Canadian arctic in search of the doomed Franklin expedition.

Neither Franklin nor any of his 128 officers and men would ever return alive. HMS Resolute found and rescued the long suffering crew of the HMS Investigator, hopelessly encased in ice where, three years earlier, she too had been searching for the lost expedition.

Three of the HMS Resolute expedition’s ships themselves became trapped in floe ice in August 1853, including Resolute, herself. There was no choice but to abandon ship, striking out across the ice pack in search of their supply ships. Most of them made it, despite egregious hardship, straggling into Beechey Island in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, between May and August of the following year.

Three of the HMS Resolute expedition’s ships themselves became trapped in floe ice in August 1853, including Resolute, herself. There was no choice but to abandon ship, striking out across the ice pack in search of their supply ships. Most of them made it, despite egregious hardship, straggling into Beechey Island in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, between May and August of the following year.

The expedition’s survivors left Beechey Island on August 29, 1854, never to return.

Meanwhile Resolute, alone and abandoned among the ice floes, continued to drift eastward at a rate of 1½ nautical miles per day.

The American whale ship George Henry discovered the drifting Resolute on September 10, 1855, 1,200 miles from her last known position. Captain James Buddington split his crew, half of them now manning the abandoned ship. Fourteen of them sailed Resolute back to their base in Groton CT, arriving on Christmas eve.

The so-called ‘Pig and Potato War” of 1859 was resolved between the British and American governments with the loss of no more than a single hog, yet a number of border disputes made the late 1850s a difficult time, for American-British relations. Senator James Mason of Virginia presented a bill in Congress to fix up the Resolute, giving her back to her Majesty Queen Victoria’s government as a token of friendship between the two nations.

$40,000 were spent on the refit, and Resolute sailed for England later that year. Commander Henry J. Hartstene presented her to Queen Victoria on December 13. HMS Resolute served in the British navy until being retired and broken up in 1879. The British government ordered two desks to be fashioned from English oak of the ship’s timbers, the work being done by the skilled cabinet makers of the Chatham dockyards. The British government presented a large partner’s desk to President Rutherford B. Hayes in 1880. A token of gratitude for HMS Resolute’s return, 24 years earlier.

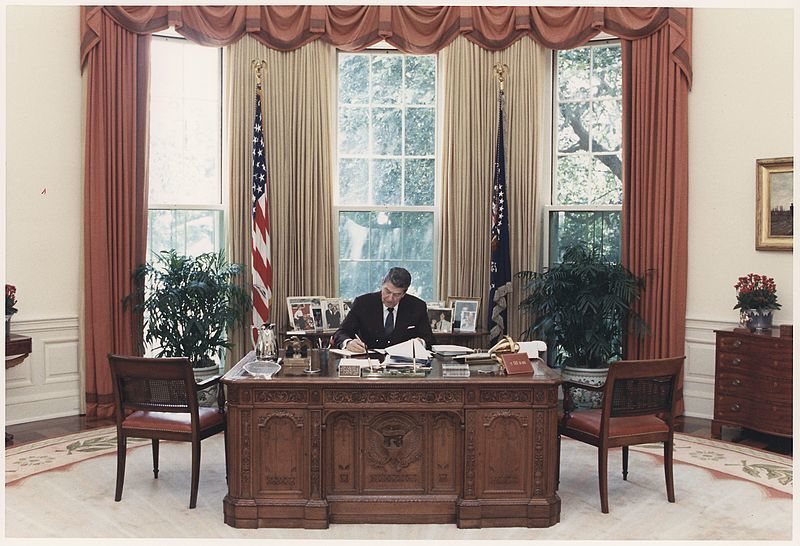

The desk, known as the Resolute Desk, has been used by nearly every American President since, whether in a private study or the oval office.

The desk, known as the Resolute Desk, has been used by nearly every American President since, whether in a private study or the oval office.

FDR had a panel installed in the opening, since he was self conscious about his leg braces. It was Jackie Kennedy who brought the desk into the Oval Office. There are pictures of JFK working at the desk, while his young son JFK, Jr., played under it.

Presidents Johnson, Nixon and Ford were the only ones not to use the Resolute desk, as LBJ allowed it to leave the White House, after the Kennedy assassination.

The Resolute Desk spent several years in the Kennedy Library and later the Smithsonian Institute, the only time the desk has been out of the White House.

Jimmy Carter returned the desk to the Oval Office, where it has remained through the Presidencies of Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Barack Obama and, thus far, Donald J. Trump.

Noble though it was, Lawrence Oates’ suicide came to naught. The last three made their final camp on March 19, with 400 miles to go. A howling blizzard descended on the tents the following day and lasted for days, as Scott, Henry “Birdie” Bowers and Dr. Edward Wilson wrote good-bye letters to mothers, wives, and others. In his final starved, frostbitten hours, Robert Falcon Scott wrote to his diary “It seems a pity, but I do not think I can write more.” In his final entry, Scott worried about the financial burden on his family, and those of the doomed expedition: “Last entry. For God’s sake look after our people”.

Noble though it was, Lawrence Oates’ suicide came to naught. The last three made their final camp on March 19, with 400 miles to go. A howling blizzard descended on the tents the following day and lasted for days, as Scott, Henry “Birdie” Bowers and Dr. Edward Wilson wrote good-bye letters to mothers, wives, and others. In his final starved, frostbitten hours, Robert Falcon Scott wrote to his diary “It seems a pity, but I do not think I can write more.” In his final entry, Scott worried about the financial burden on his family, and those of the doomed expedition: “Last entry. For God’s sake look after our people”. The last three survivors died eleven miles from their next supply depot.

The last three survivors died eleven miles from their next supply depot.

Reduced to three ships by August 1578, Drake made the straits of Magellan, emerging alone into the Pacific that September.

Reduced to three ships by August 1578, Drake made the straits of Magellan, emerging alone into the Pacific that September.

Radios of the age didn’t work across the Rockies, and the mail was erratic. The only passenger service available was run by the Yukon Southern airline, a run which locals called the “Yukon Seldom”. For construction battalions at Dawson Creek, Delta Junction and Whitehorse, it was faster to talk to each other through military officials in Washington, DC.

Radios of the age didn’t work across the Rockies, and the mail was erratic. The only passenger service available was run by the Yukon Southern airline, a run which locals called the “Yukon Seldom”. For construction battalions at Dawson Creek, Delta Junction and Whitehorse, it was faster to talk to each other through military officials in Washington, DC. Tent pegs were useless in the permafrost, while the body heat of sleeping soldiers meant waking up in mud. Partially thawed lakes meant that supply planes could use neither pontoon nor ski, as Black flies swarmed the troops by day. Hungry bears raided camps at night, looking for food.

Tent pegs were useless in the permafrost, while the body heat of sleeping soldiers meant waking up in mud. Partially thawed lakes meant that supply planes could use neither pontoon nor ski, as Black flies swarmed the troops by day. Hungry bears raided camps at night, looking for food.

NPR ran an interview about this story back in the eighties, in which an Inupiaq elder was recounting his memories. He had grown up in a world as it existed for hundreds of years, without so much as an idea of internal combustion. He spoke of the day that he first heard the sound of an engine, and went out to see a giant bulldozer making its way over the permafrost. The bulldozer was being driven by a black operator, probably one of the 97th Engineers Battalion soldiers. The old man’s comment, as best I can remember it, was a classic. “It turned out”, he said, “that the first white person I ever saw, was a black man”.

NPR ran an interview about this story back in the eighties, in which an Inupiaq elder was recounting his memories. He had grown up in a world as it existed for hundreds of years, without so much as an idea of internal combustion. He spoke of the day that he first heard the sound of an engine, and went out to see a giant bulldozer making its way over the permafrost. The bulldozer was being driven by a black operator, probably one of the 97th Engineers Battalion soldiers. The old man’s comment, as best I can remember it, was a classic. “It turned out”, he said, “that the first white person I ever saw, was a black man”.

Columbus had taken his idea of a westward trade route to the Portuguese King, to Genoa and to Venice, before he came to Ferdinand and Isabella in 1486. At that time the Spanish monarchs had a

Columbus had taken his idea of a westward trade route to the Portuguese King, to Genoa and to Venice, before he came to Ferdinand and Isabella in 1486. At that time the Spanish monarchs had a  Columbus seems not to have been impressed, describing these mermaids as “not half as beautiful as they are painted.”

Columbus seems not to have been impressed, describing these mermaids as “not half as beautiful as they are painted.”

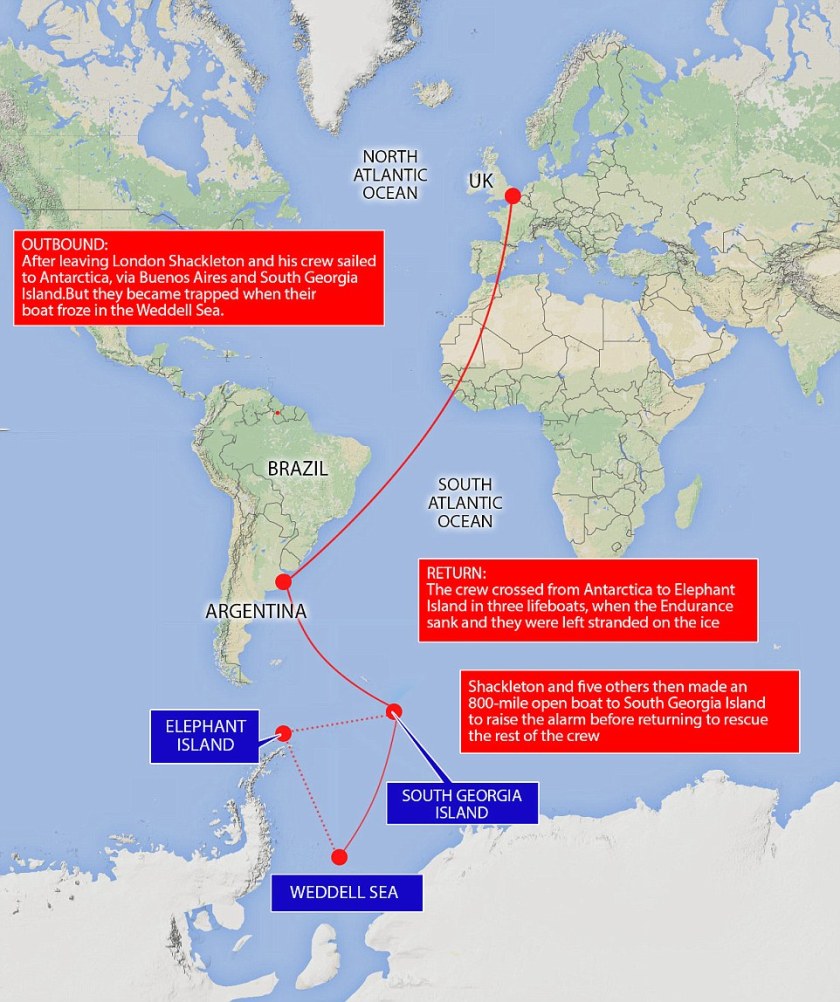

The trio arrived at the Stromness whaling station on May 20. They must have been a sight, with thick ice encrusting their long, filthy beards, and saltwater-soaked sealskin clothing rotting from their bodies. The first people they came across were children, who ran in fright at the sight of them.

The trio arrived at the Stromness whaling station on May 20. They must have been a sight, with thick ice encrusting their long, filthy beards, and saltwater-soaked sealskin clothing rotting from their bodies. The first people they came across were children, who ran in fright at the sight of them.

Most of 1803 was spent in planning and preparation, Lewis and Clark joining forces near Louisville that October. After wintering in the Indiana territory base camp in modern day Illinois, the 33-man expedition departed on May 14, 1804, accompanied by “Seaman”, a “Dogg of the Newfoundland breed”.

Most of 1803 was spent in planning and preparation, Lewis and Clark joining forces near Louisville that October. After wintering in the Indiana territory base camp in modern day Illinois, the 33-man expedition departed on May 14, 1804, accompanied by “Seaman”, a “Dogg of the Newfoundland breed”. Discovery established friendly relations with at least 24 indigenous tribes, without whose help they may have become lost or starved in the wilderness. Most were more than impressed with Lewis’ state-of-the-art pneumatic rifle, which could silently fire up to 20 rounds after being pumped full of compressed air.

Discovery established friendly relations with at least 24 indigenous tribes, without whose help they may have become lost or starved in the wilderness. Most were more than impressed with Lewis’ state-of-the-art pneumatic rifle, which could silently fire up to 20 rounds after being pumped full of compressed air. The Corps of Discovery reached the Pacific Ocean in November 1805, and set out their second winter camp in modern-day Oregon.

The Corps of Discovery reached the Pacific Ocean in November 1805, and set out their second winter camp in modern-day Oregon.

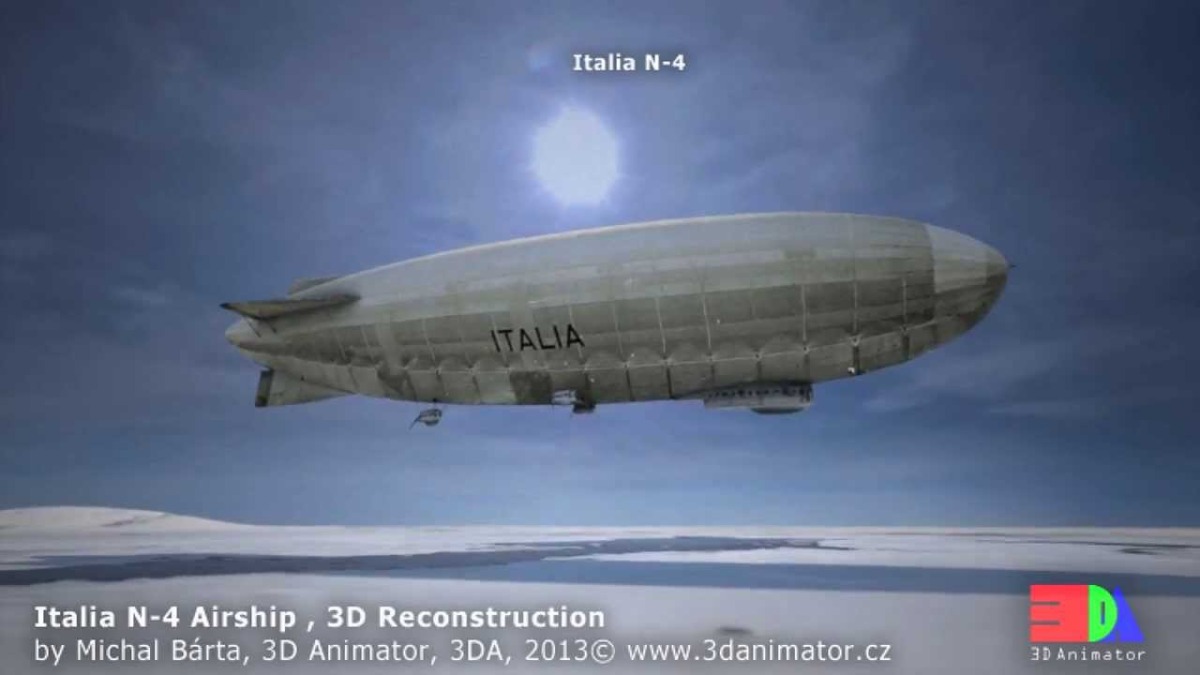

The first of five planned sorties began on May 11, before turning back only eight hours later in near blizzard conditions. The second trip took place in near perfect weather conditions and unlimited visibility, the craft covering 4,000 km (2,500 miles) and setting the stage for the third and final trip departing on May 23.

The first of five planned sorties began on May 11, before turning back only eight hours later in near blizzard conditions. The second trip took place in near perfect weather conditions and unlimited visibility, the craft covering 4,000 km (2,500 miles) and setting the stage for the third and final trip departing on May 23. envelope floated away, Chief Engineer Ettore Arduino started to throw everything he could get his hands on down to the men on the ice. These were the supplies intended for the descent to the pole, but they were now the only thing that stood between life and death. Arduino himself and the rest of the crew drifted away with the now helpless airship.

envelope floated away, Chief Engineer Ettore Arduino started to throw everything he could get his hands on down to the men on the ice. These were the supplies intended for the descent to the pole, but they were now the only thing that stood between life and death. Arduino himself and the rest of the crew drifted away with the now helpless airship.

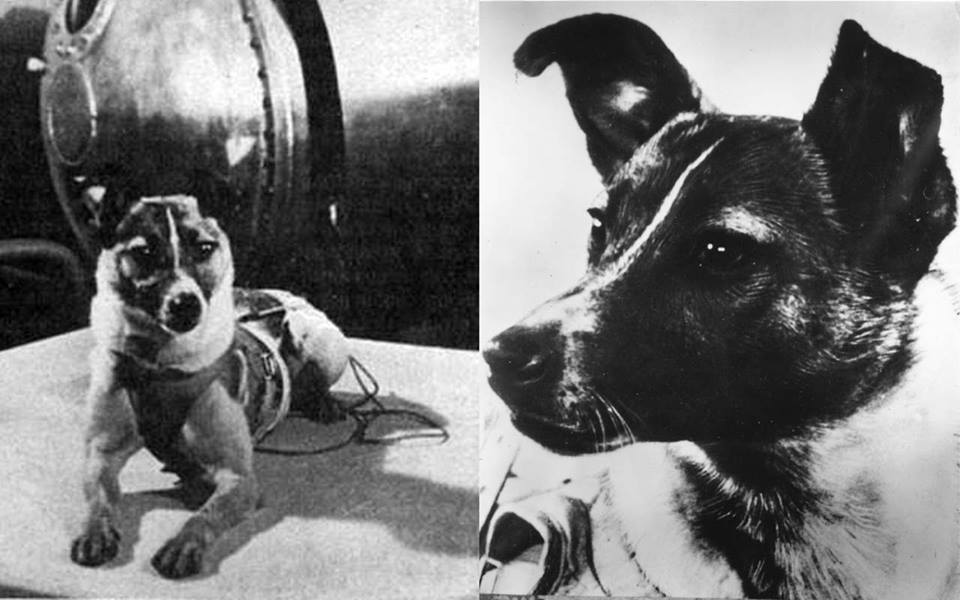

allowed her to stand, sit and lie down. Finally, it was November 3, 1957. Launch day. One of the technicians “kissed her nose and wished her bon voyage, knowing that she would not survive the flight”.

allowed her to stand, sit and lie down. Finally, it was November 3, 1957. Launch day. One of the technicians “kissed her nose and wished her bon voyage, knowing that she would not survive the flight”. In the beginning, the US News media focused on the politics of the launch. It was all about the “Space Race”, and the Soviet Union running up the score. First had been the unoccupied Sputnik 1, now Sputnik 2 had put the first living creature into space. The more smartass specimens among the American media, called the launch “Muttnik”.

In the beginning, the US News media focused on the politics of the launch. It was all about the “Space Race”, and the Soviet Union running up the score. First had been the unoccupied Sputnik 1, now Sputnik 2 had put the first living creature into space. The more smartass specimens among the American media, called the launch “Muttnik”.

As a dog lover, I feel the need to add a more upbeat postscript, to this thoroughly depressing story.

As a dog lover, I feel the need to add a more upbeat postscript, to this thoroughly depressing story.

You must be logged in to post a comment.