The accident began as a test. A carefully planned series of events intending to simulate a station blackout at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, in the Soviet Socialist Republic of Ukraine.

This most titanic of disasters began with a series of smaller mishaps. Safety systems intentionally turned off, reactor operators failing to follow checklists, inherent design flaws in the reactor itself.

Over the night of April 25-26, 1986, a nuclear fission chain reaction expanded beyond control at reactor #4, flashing water to super-heated steam resulting in a violent explosion and open air graphite fire. Massive amounts of nuclear material were expelled into the atmosphere during this explosive phase, equaled only by that released over the following nine days by intense updrafts created by the fire. Radioactive material rained down over large swaths of the western USSR and Europe, some 60% in the Republic of Belarus.

It was the most disastrous nuclear power plant accident in history and one of only two such accidents classified as a level 7, the maximum classification on the International Nuclear Event Scale. The other was the 2011 tsunami and subsequent nuclear disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi reactor, in Japan.

One operator died in the steam-blast phase of the accident, a second resulting from a catastrophic dose of radiation. 600 Soviet helicopter pilots risked lethal radiation, dropping 5,000 metric tons of lead, sand and boric acid in the effort to seal off the spread.

Remote controlled, robot bulldozers and carts, soon proved useless. Valery Legasov of the Kurchatov Institute of Atomic Energy in Moscow, explains: “[W]e learned that robots are not the great remedy for everything. Where there was very high radiation, the robot ceased to be a robot—the electronics quit working.”

Soldiers in heavy protective gear shoveled the most highly radioactive materials, “bio-robots” allowed to spend a one-time maximum of only forty seconds on the rooftops of surrounding buildings. Even so, some of these “Liquidators” report having done so, five or six times.

In the aftermath, 237 suffered from Acute Radiation Sickness (ARS), 31 of whom died in the following three months. Fourteen more died of radiation induced cancers, over the following ten years.

The death toll could have been far higher, but for the heroism of first responders. Anatoli Zakharov, a fireman stationed in Chernobyl since 1980, replied to remarks that firefighters believed this to be an ordinary electrical fire. “Of course we knew! If we’d followed regulations, we would never have gone near the reactor. But it was a moral obligation – our duty. We were like kamikaze“.

The concrete sarcophagus designed and built to contain the wreckage has been called the largest civil engineering project in history, involving no fewer than a quarter-million construction workers, every one of whom received a lifetime maximum dose of radiation. By December 10 the structure was nearing completion. The #3 reactor at Chernobyl continued to produce electricity, until 2000.

Officials of the top-down Soviet state first downplayed the disaster. Asked by one Ukrainian official, “How are the people?“, acting minister of Internal Affairs Vasyl Durdynets replied that there was nothing to be concerned about: “Some are celebrating a wedding, others are gardening, and others are fishing in the Pripyat River.”

As the scale of the disaster became apparent, civilians were at first ordered to shelter in place. A 10-km exclusion zone was enacted within the first 36 hours, resulting in the hurried evacuation of some 49,000. The exclusion zone was tripled to 30-km within a week, leading to the evacuation of 68,000 more. Before it was over, some 350,000 were moved away, never to return.

The chaos of these evacuations, can scarcely be imagined. Confused adults. Crying children. Howling dogs. Shouting soldiers, barking orders and herding the now-homeless onto waiting buses, by the tens of thousands. Dogs and cats, beloved companion animals, were ordered left behind. Evacuees were never told. There would be no return.

There were countless and heartbreaking scenes of final abandonment, of mewling cats, and whimpering dogs. Belorussian writer Svetlana Alexievich compiled hundreds of interviews into a single monologue, an oral history of the forgotten. The devastating Chernobyl Prayer tells the story of: “dogs howling, trying to get on the buses. Mongrels, Alsatians. The soldiers were pushing them out again, kicking them. They ran after the buses for ages.” Heartbroken families pinned notes to their doors: “Don’t kill our Zhulka. She’s a good dog.”

There would be no mercy. Squads of soldiers were sent to shoot those animals, left behind. Most died. Some escaped discovery, and survived.

Today the descendants of those dogs, some 900 in number occupy an exclusion zone some 1,600 square miles, slightly smaller than the American state, of Delaware. They are not alone.

In 1998, 31 specimens of the Przewalski Horse were released into the exclusion zone which now serves as a de facto wildlife preserve. Not to be confused with the American mustang or the Australian brumby, the Przewalski Horse is a truly wild horse and not the feral descendant, of domesticated animals.

Named by the 19th century Polish-Russian naturalist Nikołaj Przewalski, Equus ferus przewalskii split from ancestors of the domestic Equus caballus some 38,000 to 160,000 years ago, forming a divergent species where neither taxonomic group is descended, from the other. The last Przewalski stallion was observed in the wild in 1969. The species is considered extinct in the wild, since that time.

Today approximately 100 Przewalski horses roam the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone one of the larger populations of this, possibly the last of the truly wild horses, alive today.

In 2016, US government wildlife biologist Sarah Webster worked at the University of Georgia. Webster and others used camera traps to demonstrate how wildlife had colonized the exclusion zone, even the most contaminated parts. A scientific paper on the subject is linked HERE, if you’re interested.

Ironically, the threat posed by humans outside the exclusion zone is greater for some species than that posed by radiation, within the zone. Wildlife spotted within the exclusion zone include wolves, badgers, swans, moose, elk, turtles, deer, foxes, beavers, boars, bison, mink, hares, otters, lynx, eagles, rodents, storks, bats and owls.

Not all animals thrive in this place. Invertebrates like spiders, butterflies and dragonflies are noticeably absent, likely because of eggs laid in surface soil layers which remain, contaminated. Radionuclides settled in lake sediments effect populations of fish, frogs, crustaceans and insect larvae. Birds in the exclusion zone have difficulty reproducing. Such animals who do successfully reproduce often demonstrate albinism, deformed beaks and feathers, malformed sperm cells and cataracts.

Tales abound of giant mushrooms, six-pawed rabbits and three headed dogs. While some such stories are undoubtedly exaggerated few such mutations survive the first few hours and those who do are unlikely to pass on the more egregious deformities.

Far from the post-apocalyptic wasteland of imagination the Chernobyl exclusion zone is a thriving preserve for some but not all, wildlife. Which brings us back to the dogs. Caught in a twilight zone neither feral nor domestic the dogs of Chernobyl are neither able to compete in the wild nor are many of them candidates for adoption, due to radiation toxicity.

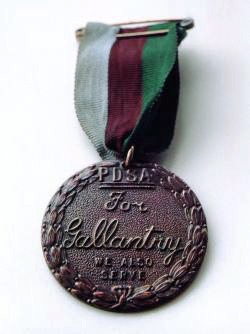

Since September 2017, a partnership between the SPCA International and the US-based 501(c)(3) non-profit CleanFutures.org has worked to provide for the veterinary needs of these defenseless creatures. Over 450 animals have been tested for radiation exposure, given medical care, vaccinations, and spayed or neutered, to bring populations within manageable limits. Many have been socialized for human interaction and successfully decontaminated, available for adoption into homes in Ukraine and North America.

For most there is no future beyond this place and a life expectancy unlikely to exceed a span of five years.

Thirty five years after the world’s most devastating nuclear disaster a surprising number of people work in this place, on a rotating basis. Guards are stationed at access points whose job it is to control who gets in and to keep out unauthorized visitors, known as “stalkers”.

BBC wrote in April of this year about the strange companionship sprung up between these guards, and the dogs of Chernobyl. Jonathon Turnbull is a PhD candidate in geography at the University of Cambridge. He was the first outsider to recognize the relationship and gave the guards disposable cameras, with which to record the lives of these abandoned animals. The guards around this toxic sanctuary had but a single request: “please, please – bring food for the dogs”.

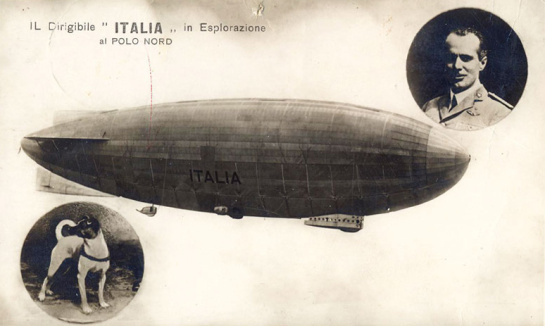

Two years earlier, the Norge (“NOR-gay”) had demonstrated that such an airship, could reach the north pole. This time they were coming back, for further exploration.

Two years earlier, the Norge (“NOR-gay”) had demonstrated that such an airship, could reach the north pole. This time they were coming back, for further exploration. The first of five planned sorties began on May 11, before turning back only eight hours later in near-blizzard conditions. The second trip took place in virtually perfect weather conditions with unlimited visibility. The craft covered 4,000 km (2,500 miles), setting the stage for the third and final trip.

The first of five planned sorties began on May 11, before turning back only eight hours later in near-blizzard conditions. The second trip took place in virtually perfect weather conditions with unlimited visibility. The craft covered 4,000 km (2,500 miles), setting the stage for the third and final trip.

An estimated 4,000 to 93,000 died in the aftermath of the accident, many of whom, were children.

An estimated 4,000 to 93,000 died in the aftermath of the accident, many of whom, were children. Officials of the top-down Soviet state first downplayed the disaster. Asked by one Ukrainian official, “How are the people?“, acting minister of Internal Affairs Vasyl Durdynets replied there was nothing to be concerned about: “Some are celebrating a wedding, others are gardening, and others are fishing in the Pripyat River.”

Officials of the top-down Soviet state first downplayed the disaster. Asked by one Ukrainian official, “How are the people?“, acting minister of Internal Affairs Vasyl Durdynets replied there was nothing to be concerned about: “Some are celebrating a wedding, others are gardening, and others are fishing in the Pripyat River.” The chaos of these forced evacuations, can scarcely be imagined. Confused adults. Crying children. Howling dogs. Shouting soldiers, barking orders and herding now-homeless civilians onto waiting trains and vehicles by the tens of thousands. Dogs and cats, beloved companion animals and lifelong family members, were abandoned to fend for themselves.

The chaos of these forced evacuations, can scarcely be imagined. Confused adults. Crying children. Howling dogs. Shouting soldiers, barking orders and herding now-homeless civilians onto waiting trains and vehicles by the tens of thousands. Dogs and cats, beloved companion animals and lifelong family members, were abandoned to fend for themselves. There were countless and heartbreaking scenes of final abandonment, of mewling cats, and whimpering dogs. Belorussian writer Svetlana Alexievich compiled hundreds of interviews into a single monologue, an oral history of the forgotten. The devastating Chernobyl Prayer tells the story of: “dogs howling, trying to get on the buses. Mongrels, Alsatians. The soldiers were pushing them out again, kicking them. They ran after the buses for ages.”

There were countless and heartbreaking scenes of final abandonment, of mewling cats, and whimpering dogs. Belorussian writer Svetlana Alexievich compiled hundreds of interviews into a single monologue, an oral history of the forgotten. The devastating Chernobyl Prayer tells the story of: “dogs howling, trying to get on the buses. Mongrels, Alsatians. The soldiers were pushing them out again, kicking them. They ran after the buses for ages.”  There was no mercy. Squads of soldiers were sent to shoot the animals, left behind. Heartbroken families pinned notes to their doors: “Don’t kill our Zhulka. She’s a good dog.” Most of these abandoned pets, were shot. Some escaped notice, and survived.

There was no mercy. Squads of soldiers were sent to shoot the animals, left behind. Heartbroken families pinned notes to their doors: “Don’t kill our Zhulka. She’s a good dog.” Most of these abandoned pets, were shot. Some escaped notice, and survived. Later on, plant management hired someone, to kill the 1,000 or so dogs still remaining. The story is, the worker refused.

Later on, plant management hired someone, to kill the 1,000 or so dogs still remaining. The story is, the worker refused. Today, untold numbers of stray dogs live in the towns of Chernobyl, Pripyat and surrounding villages. Descendants of those left behind, back in 1986. Ill equipped to survive in the wild and driven from forests by wolves and other predators, they forage as best they can among abandoned streets and buildings, of the 1,000-mile exclusion zone. For some, radiation can be found in their fur. Few live beyond the age of six but, all is not bleak.

Today, untold numbers of stray dogs live in the towns of Chernobyl, Pripyat and surrounding villages. Descendants of those left behind, back in 1986. Ill equipped to survive in the wild and driven from forests by wolves and other predators, they forage as best they can among abandoned streets and buildings, of the 1,000-mile exclusion zone. For some, radiation can be found in their fur. Few live beyond the age of six but, all is not bleak. Since September 2017, a partnership between the SPCA International and the US-based 501(c)(3) non-profit

Since September 2017, a partnership between the SPCA International and the US-based 501(c)(3) non-profit  Some have been successfully decontaminated and socialized for human interaction. In 2018, the first batch became available for adoption into homes in Ukraine and North America, some forty puppies and dogs.

Some have been successfully decontaminated and socialized for human interaction. In 2018, the first batch became available for adoption into homes in Ukraine and North America, some forty puppies and dogs. Believe it or not there are visitors to the area. People actually go on tours of the region but they’re strictly warned. No matter how adorable, do not pet, cuddle nor even touch any puppy or dog who has not been through rigorous decontamination.

Believe it or not there are visitors to the area. People actually go on tours of the region but they’re strictly warned. No matter how adorable, do not pet, cuddle nor even touch any puppy or dog who has not been through rigorous decontamination.

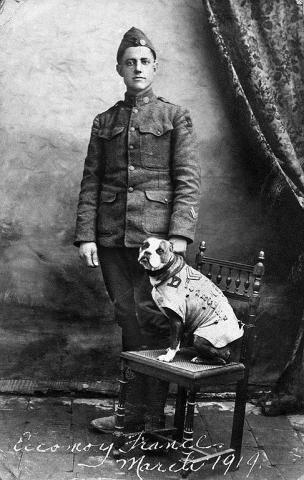

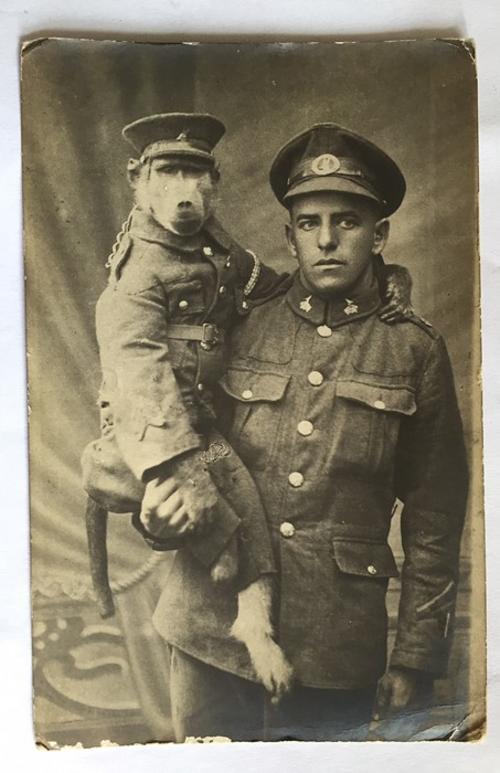

By the last year of the Great War, the French, British and Belgians had at least 20,000 dogs on the battlefield. Imperial Germany had 30,000.

By the last year of the Great War, the French, British and Belgians had at least 20,000 dogs on the battlefield. Imperial Germany had 30,000.

Stubby saw his first action at Chemin des Dames. Since the boom of artillery fire didn’t faze him, he learned to follow the men’s example of ducking when the big ones came close. It became a great game to see who could hit the dugout, first. After a few days, the guys were watching him for a signal. Stubby was always the first to hear incoming fire. We can only guess how many lives were spared by his early warning.

Stubby saw his first action at Chemin des Dames. Since the boom of artillery fire didn’t faze him, he learned to follow the men’s example of ducking when the big ones came close. It became a great game to see who could hit the dugout, first. After a few days, the guys were watching him for a signal. Stubby was always the first to hear incoming fire. We can only guess how many lives were spared by his early warning.

Private Albert Marr’s Chacma baboon

Private Albert Marr’s Chacma baboon

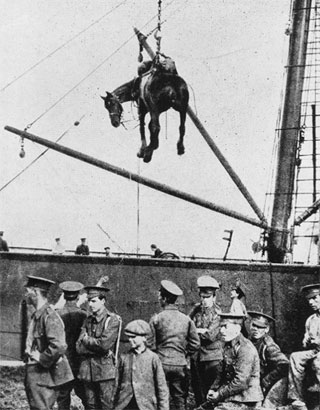

Horsepower was indispensable throughout the war from cavalry and mounted infantry to reconnaissance and messenger service, as well as pulling artillery, ambulances, and supply wagons. With the value of horses to the war effort and difficulty in their replacement, the loss of a horse was a greater tactical problem in some areas, than the loss of a man.

Horsepower was indispensable throughout the war from cavalry and mounted infantry to reconnaissance and messenger service, as well as pulling artillery, ambulances, and supply wagons. With the value of horses to the war effort and difficulty in their replacement, the loss of a horse was a greater tactical problem in some areas, than the loss of a man. Few ever returned. An estimated three quarters died of wretched working conditions. Exhaustion. The frozen, sucking mud of the western front. The mud-borne and respiratory diseases. The gas, artillery and small arms fire. An estimated eight million horses were killed on all sides, enough to line up in Boston and make it all the way to London four times, if such a thing were possible.

Few ever returned. An estimated three quarters died of wretched working conditions. Exhaustion. The frozen, sucking mud of the western front. The mud-borne and respiratory diseases. The gas, artillery and small arms fire. An estimated eight million horses were killed on all sides, enough to line up in Boston and make it all the way to London four times, if such a thing were possible.

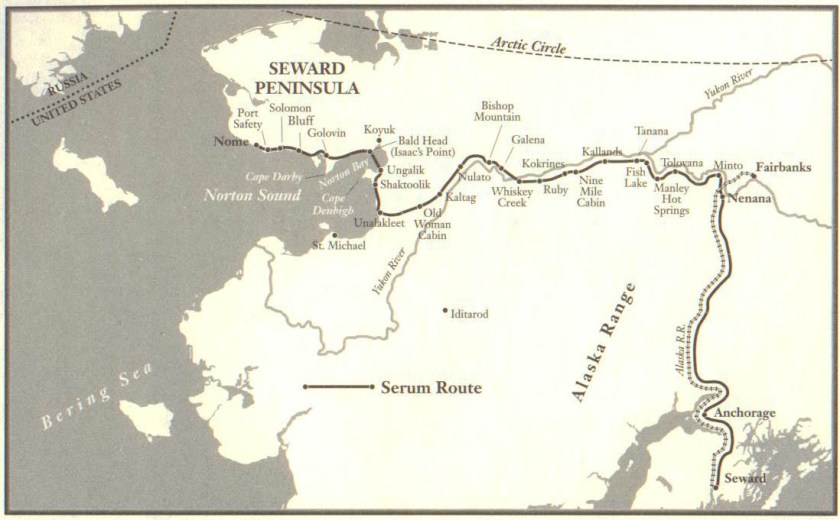

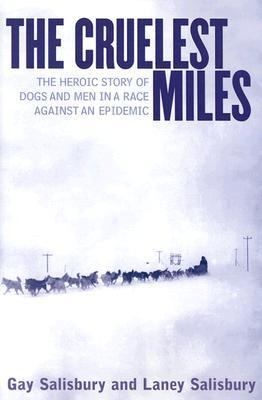

Dr. Curtis Welch practiced medicine in Nome, Alaska, in 1925. Several children became ill with what he first diagnosed as tonsillitis. More came down with sore throats, early sufferers beginning to die as Welch observed the pseudomembrane of diphtheria. Dr. Welch had ordered fresh antitoxin the year before, but the shipment hadn’t arrived by the time the ports froze over. By January, all the serum in Nome was expired.

Dr. Curtis Welch practiced medicine in Nome, Alaska, in 1925. Several children became ill with what he first diagnosed as tonsillitis. More came down with sore throats, early sufferers beginning to die as Welch observed the pseudomembrane of diphtheria. Dr. Welch had ordered fresh antitoxin the year before, but the shipment hadn’t arrived by the time the ports froze over. By January, all the serum in Nome was expired.

20 mushers and 150 dogs or more had covered 674 miles in 5 days, 7½ hours, a distance that normally took the mail relay 2-3 weeks. Not a single serum ampule was broken.

20 mushers and 150 dogs or more had covered 674 miles in 5 days, 7½ hours, a distance that normally took the mail relay 2-3 weeks. Not a single serum ampule was broken.

“The once tight fabric covering the wings and fuselage was weak from all the rough landings as well as the wind and rain. Dirt and oil caked the engine and prop. Wires for the rudders and elevators hung from the sides of the fuselage.” Even in such disrepair, the pilots and mechanics thought one of the planes could be ready to go Nome in just three days, a flight they thought would take no more than 6-hours”.

“The once tight fabric covering the wings and fuselage was weak from all the rough landings as well as the wind and rain. Dirt and oil caked the engine and prop. Wires for the rudders and elevators hung from the sides of the fuselage.” Even in such disrepair, the pilots and mechanics thought one of the planes could be ready to go Nome in just three days, a flight they thought would take no more than 6-hours”.

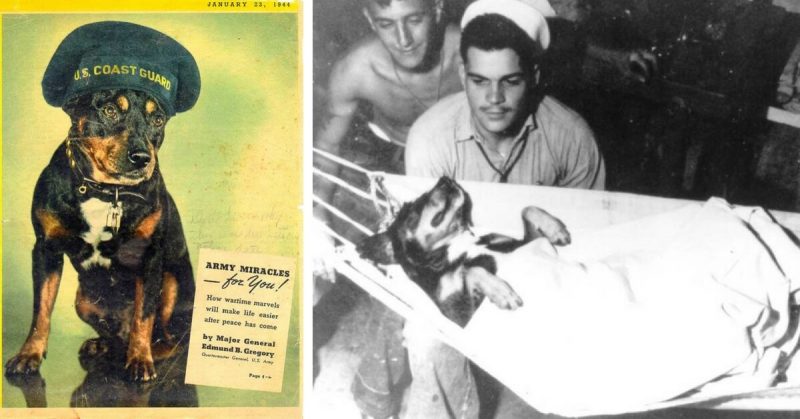

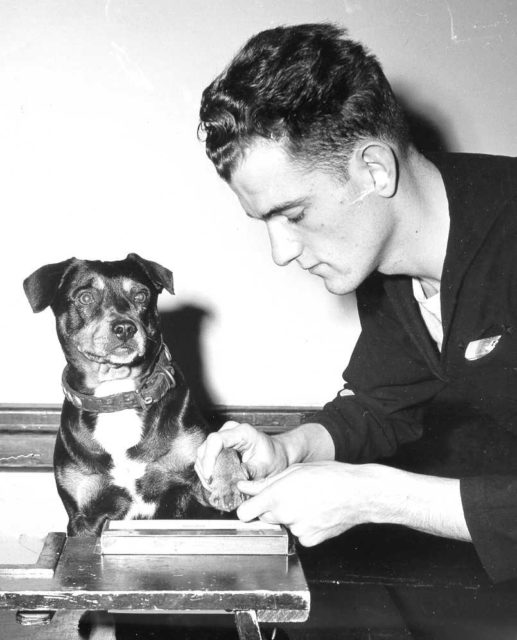

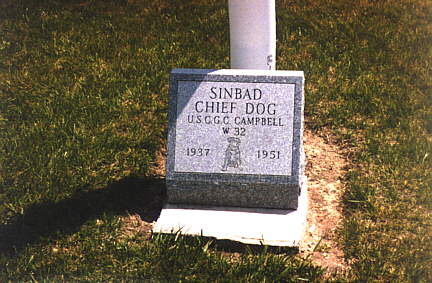

In the winter of 1937, the Coast Guard cutter USCGC George W. Campell steamed out of New York harbor, patrolling the east coast with a mission of life-saving and national defense. The night before, Chief Boatswain’s Mate A. A. “Blackie” Roth (the name is also given as “Rother”) had given his girlfriend, a puppy. She couldn’t keep him, the landlord wouldn’t allow it. No other crewman could take the small dog. It was either leave him astray and hope for the best, or smuggle the puppy on board.

In the winter of 1937, the Coast Guard cutter USCGC George W. Campell steamed out of New York harbor, patrolling the east coast with a mission of life-saving and national defense. The night before, Chief Boatswain’s Mate A. A. “Blackie” Roth (the name is also given as “Rother”) had given his girlfriend, a puppy. She couldn’t keep him, the landlord wouldn’t allow it. No other crewman could take the small dog. It was either leave him astray and hope for the best, or smuggle the puppy on board. Sinbad’s favorite toys were the large metal washers which he’d hide, until someone came to play with him. They even built him a hammock, much more comfy to sleep in, in those long Atlantic swells.

Sinbad’s favorite toys were the large metal washers which he’d hide, until someone came to play with him. They even built him a hammock, much more comfy to sleep in, in those long Atlantic swells.

You must be logged in to post a comment.