Most of us grew up learning that 600,000+ Americans were killed in the Civil War. 618,222 to be precise, more than the combined totals of every conflict in which the United States has been involved, from the Revolution to the War on Terror. Recently, sophisticated data analysis techniques have been applied to newly digitized 19th century census figures, indicating that even that figure may be understated.

The actual number may lie somewhere between 650,000 and 850,000.

The cataclysm of the Civil War would leave in its wake animosities which would take generations to heal. “Reconstruction” would be 12 years in the making, but some never did reconcile themselves to the war’s outcome. Vicksburg, Mississippi, which fell after a long siege on July 4, 1863, would not celebrate another Independence Day for 70 years.

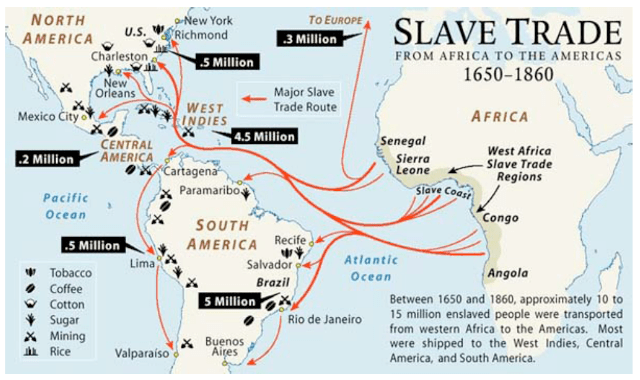

In 1865, Emperor Dom Pedro II of Brazil wanted to encourage domestic cultivation of cotton. Men like Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee advised southerners against emigration, but the Brazilian Emperor offered transportation subsidies, cheap land and tax breaks to those who would move.

Colonel William Hutchinson Norris, veteran of the Mexican American War and former member of the Alabama House of Representatives and later State Senator, was the first to make the move. Together with his son Robert and 30 families of the former Confederacy, Norris arrived in Rio de Janeiro on December 27, 1865, aboard the ship “South America”.

The numbers are hazy, but port records indicate that somewhere between ten and twenty thousand former Confederates moved to Brazil in the twenty years following the Civil War. A great uncle of former First Lady Rosalynn Carter, was one.

Some of these “Confederados” settled in the urban areas of São Paulo, most made their homes in the northern Amazon region around present-day Santa Bárbara d’Oeste and a place the locals called “Vila dos Americanos”, and the inhabitants called “Americana”. Some would return to the newly re-united states. Most would never return, and their ancestors, Portuguese speaking Brazilians all, remain there to this day.

Confederados earned a reputation for honesty and hard work, and Dom Pedro’s program was judged a success by immigrant and government alike. The settlers brought modern cultivation techniques and new food crops, all of which were quickly adopted by native Brazilian farmers.

Small wonder. Mark Twain once wrote “The true Southern watermelon is a boon apart, and not to be mentioned with common things. It is chief of this world’s luxuries, king by the grace of God over all the fruits of the earth. When one has tasted it, he knows what the angels eat. It was not a Southern watermelon that Eve took; we know it because she repented”.

That first generation kept to itself for the most part, building themselves Baptist churches and town squares, while traditional southern dishes like barbecue, buttermilk biscuits, vinegar pie and southern fried chicken did their own sort of culinary diplomacy with native populations.

Slavery remained legal in Brazil until 1888, but this nation of 51% African or mixed-race ancestry (according to the 2010 census), seems more interested in understanding and celebrating their past, than tearing their culture apart over it.

Today, descendants of those original Confederados preserve their cultural heritage through the Associação Descendência Americana (American Descendants Association), with an annual festival called the Festa Confederada. There you’ll find hoop skirts and uniforms in gray and butternut, along with the food, the music and the dances of the antebellum South.

There you will find the Confederate battle flag, as well. It seems that Brazilians have thus far resisted that peculiar urge which afflicts Isis and the American Left, to destroy the symbols of their own history.

In 2016, the New York Times reported on the May celebration of the Festa Confederada, of Santa Bárbara d’Oeste:

‘“This is a joyful event,” said Carlos Copriva, 52, a security guard who described his ancestry as a mix of Hungarian and Italian. He was wearing a Confederate kepi cap that he had bought online as he and his wife, Raquel Copriva, who is Afro-Brazilian, strolled through the bougainvillea-shaded cemetery. Smiling at her husband, Ms. Copriva, 43, who works as a maid, gazed at the graves around them. “We know there was slavery in both the United States and Brazil, but look at us now, white and black, together in this place,” she said while pointing to the tombstones. “Maybe we’re the future and they’re the past.”’

A “Fidelity Medallion” was awarded to three militia men in 1780, for the capture of

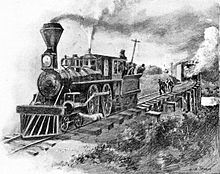

A “Fidelity Medallion” was awarded to three militia men in 1780, for the capture of  An Army version of the medal was created the following July, first awarded to six Union soldiers for hijacking the Confederate locomotive, “The General”. Leader of the raid James Andrews was caught and hanged as a Union spy. He alone was judged ineligible for the medal of honor, as he was a civilian.

An Army version of the medal was created the following July, first awarded to six Union soldiers for hijacking the Confederate locomotive, “The General”. Leader of the raid James Andrews was caught and hanged as a Union spy. He alone was judged ineligible for the medal of honor, as he was a civilian. Few soldiers on the Civil War battlefield had a quicker route to death’s door, than the color bearer. National and regimental flags were all-important sources of inspiration and communication.

Few soldiers on the Civil War battlefield had a quicker route to death’s door, than the color bearer. National and regimental flags were all-important sources of inspiration and communication.

Father

Father

The Union crossing of the Rappahannock was intended to be a surprise, depending on pontoons coming down from Washington to meet up with General Ambrose Burnside’s Union army in Falmouth, across the river from Fredericksburg.

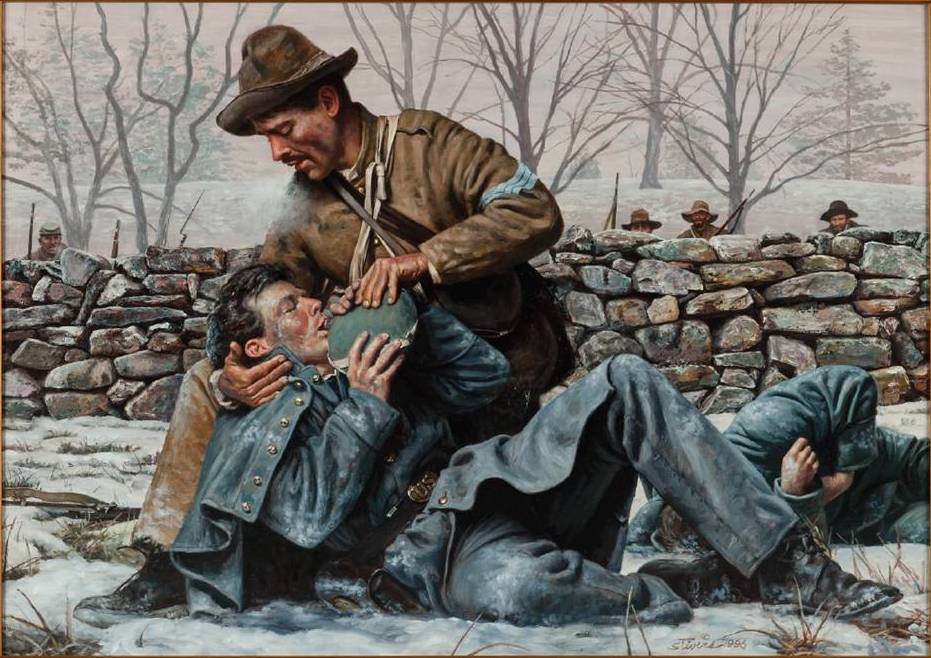

The Union crossing of the Rappahannock was intended to be a surprise, depending on pontoons coming down from Washington to meet up with General Ambrose Burnside’s Union army in Falmouth, across the river from Fredericksburg. In contrast to the swampy approaches on the Confederate right, 5,000 soldiers under James Longstreet looked out from behind the stone wall on Marye’s Heights to an open plain, crossed from left to right by a mill run, 5′ deep, 15′ wide and filled with 3′ of freezing water.

In contrast to the swampy approaches on the Confederate right, 5,000 soldiers under James Longstreet looked out from behind the stone wall on Marye’s Heights to an open plain, crossed from left to right by a mill run, 5′ deep, 15′ wide and filled with 3′ of freezing water.

Lincoln signed, dated and titled the Bliss copy. This is the version inscribed on the South wall of the Lincoln Memorial.

Lincoln signed, dated and titled the Bliss copy. This is the version inscribed on the South wall of the Lincoln Memorial.

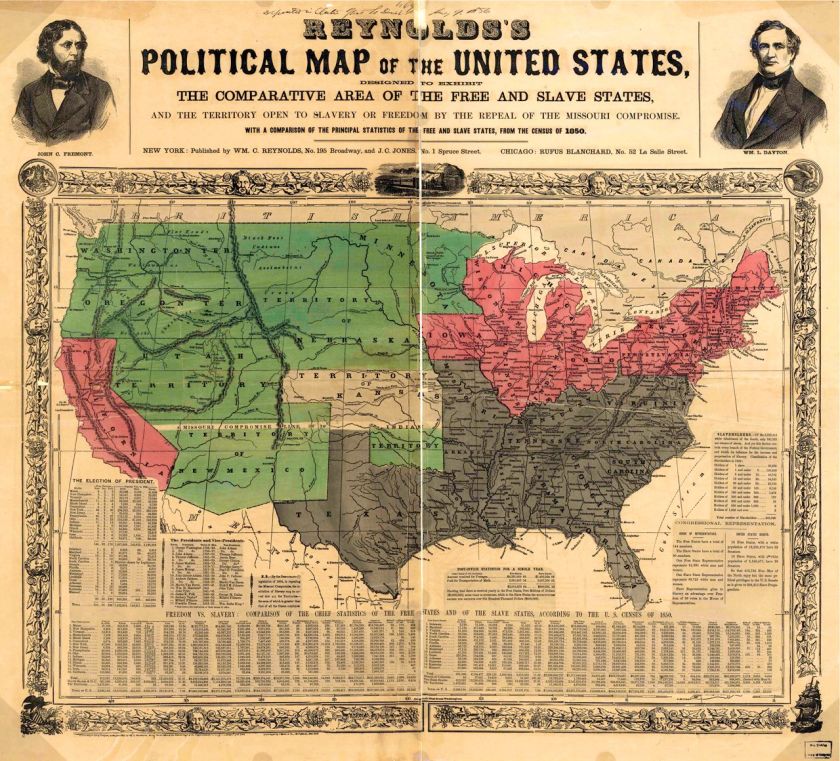

Sectional differences grew and sharpened in the years that followed. A member of Congress from Kentucky killed a fellow congressman from Maine. A Congressman from South Carolina all but beat a Massachusetts Senator to death with a

Sectional differences grew and sharpened in the years that followed. A member of Congress from Kentucky killed a fellow congressman from Maine. A Congressman from South Carolina all but beat a Massachusetts Senator to death with a

In New York city and “upstate” alike, economic ties with the south ran deep. 40¢ of every dollar paid for southern cotton stayed in New York, in the form of insurance, shipping, warehouse fees and profits.

In New York city and “upstate” alike, economic ties with the south ran deep. 40¢ of every dollar paid for southern cotton stayed in New York, in the form of insurance, shipping, warehouse fees and profits. “Town Line”, a hamlet on the village’s eastern boundary, put it to a vote. In the fall of 1861, residents gathered in the old schoolhouse-turned blacksmith’s shop. By a margin of 85 to 40, Town Line, New York voted to secede from the Union.

“Town Line”, a hamlet on the village’s eastern boundary, put it to a vote. In the fall of 1861, residents gathered in the old schoolhouse-turned blacksmith’s shop. By a margin of 85 to 40, Town Line, New York voted to secede from the Union. A rumor went around in 1864, that a

A rumor went around in 1864, that a  Even Georgians couldn’t help themselves from commenting. 97-year-old Confederate General T.W. Dowling said: “We been rather pleased with the results since we rejoined the Union. Town Line ought to give the United States another try“. Judge A.L. Townsend of Trenton Georgia commented “Town Line ought to give the United States a good second chance“.

Even Georgians couldn’t help themselves from commenting. 97-year-old Confederate General T.W. Dowling said: “We been rather pleased with the results since we rejoined the Union. Town Line ought to give the United States another try“. Judge A.L. Townsend of Trenton Georgia commented “Town Line ought to give the United States a good second chance“. Fireman’s Hall became the site of the barbecue, “The old blacksmith shop where the ruckus started” being too small for the assembled crowd. On October 28, 1945, residents adopted a resolution suspending its 1861 ordinance of secession, by a vote of 90-23. The Stars and Bars of the Lost Cause was lowered for the last time, outside the old blacksmith shop.

Fireman’s Hall became the site of the barbecue, “The old blacksmith shop where the ruckus started” being too small for the assembled crowd. On October 28, 1945, residents adopted a resolution suspending its 1861 ordinance of secession, by a vote of 90-23. The Stars and Bars of the Lost Cause was lowered for the last time, outside the old blacksmith shop.

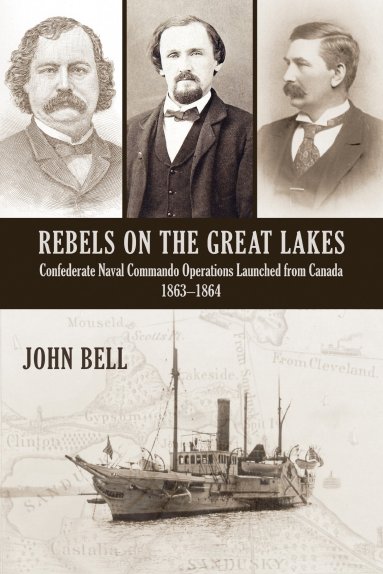

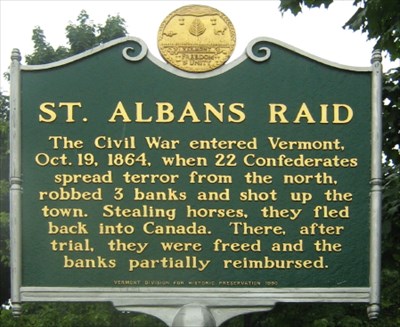

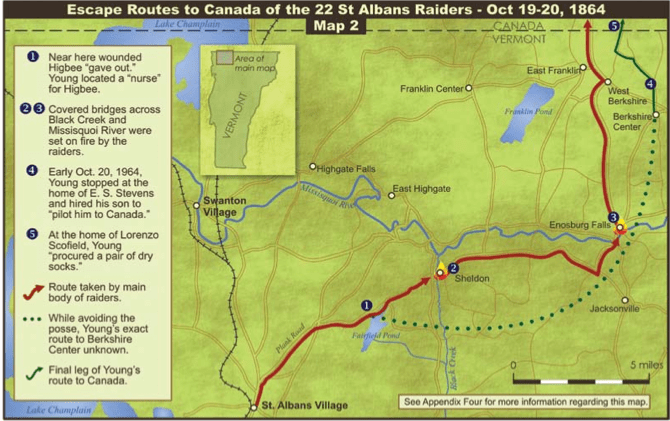

In April 1864, President Jefferson Davis dispatched former Secretary of the Interior Jacob Thompson, ex-Alabama Senator Clement Clay, and veteran Confederate spy Captain Thomas Henry Hines to Toronto, with the mission of raising hell in the North.

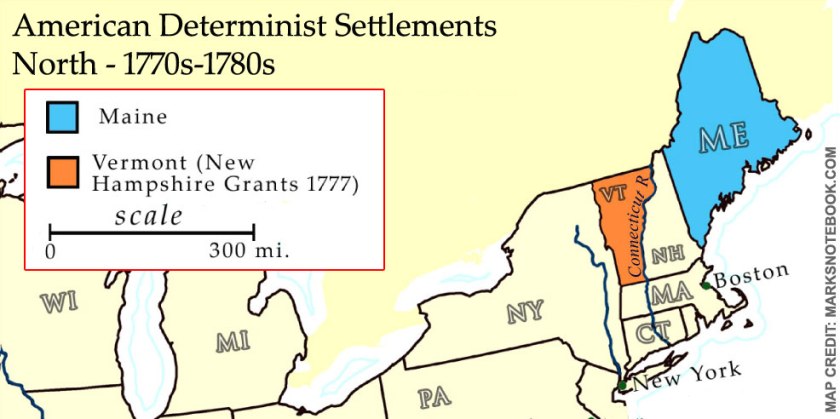

In April 1864, President Jefferson Davis dispatched former Secretary of the Interior Jacob Thompson, ex-Alabama Senator Clement Clay, and veteran Confederate spy Captain Thomas Henry Hines to Toronto, with the mission of raising hell in the North. The Confederate invasion of Maine never materialized, thanks in large measure to counter-espionage efforts by Union agents.

The Confederate invasion of Maine never materialized, thanks in large measure to counter-espionage efforts by Union agents.

The group was arrested on returning to Canada and held in Montreal. The Lincoln administration sought extradition, but the Canadian court decided otherwise, ruling that the raiders were under military orders at the time, and neutral Canada could not extradite them to America. The $88,000 found with the raiders, was returned to Vermont.

The group was arrested on returning to Canada and held in Montreal. The Lincoln administration sought extradition, but the Canadian court decided otherwise, ruling that the raiders were under military orders at the time, and neutral Canada could not extradite them to America. The $88,000 found with the raiders, was returned to Vermont.

Quantrill fled to Texas after the raid on Lawrence, and was later killed in a Union ambush near Taylorsville, Kentucky. His band broke up into several smaller groups, with some joining the Confederate army.

Quantrill fled to Texas after the raid on Lawrence, and was later killed in a Union ambush near Taylorsville, Kentucky. His band broke up into several smaller groups, with some joining the Confederate army.

Sallie’s first battle came at Cedar Mountain, in 1862. No one thought of sending her to the rear before things got hot, so she took up her position with the colors, barking ferociously at the adversary. There she remained throughout the entire engagement, as she did at Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, and Spotsylvania. They said she only hated three things: Rebels, Democrats, and Women.

Sallie’s first battle came at Cedar Mountain, in 1862. No one thought of sending her to the rear before things got hot, so she took up her position with the colors, barking ferociously at the adversary. There she remained throughout the entire engagement, as she did at Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, and Spotsylvania. They said she only hated three things: Rebels, Democrats, and Women.

“Sallie was a lady,

“Sallie was a lady,

You must be logged in to post a comment.