At different times and places, a white feather has carried different meanings. For those inclined toward New-Age, the presence of a white feather is proof that Guardian Angels are near. For the Viet Cong and NVA Regulars who were his prey, the “Lông Trắng” (“White Feather”) symbolized the deadliest menace of the American war effort in Vietnam, USMC Scout Sniper Carlos Hathcock, who wore one in his bush hat. Following the Battle of Crécy in 1346, Edward of Woodstock, Prince of Wales, plucked three white ostrich feathers from the dead body of the blind King John of Bohemia. To this day, those feathers appear in the coat of arms, of the prince of Wales.

The Edward and John who faced one another over the field at Crécy, could be described in many ways. Cowardice is not one of them. For the men of the WW1 generation, a white feather represented precisely that.

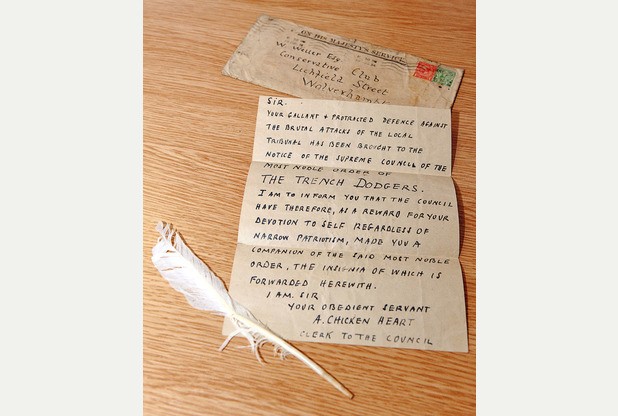

In August 1914, seventy-three year old British Admiral Charles Cooper Penrose-Fitzgerald organized a group of thirty women, to give out white feathers to men not in uniform. The point was clear enough. To gin up enough manpower, to feed the needs of a war so large as to gobble up a generation, and spit out the pieces.

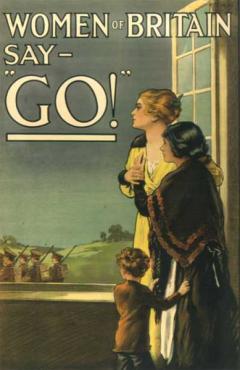

Lord Horatio Kitchener supported the measure, saying “The women could play a great part in the emergency by using their influence with their husbands and sons to take their proper share in the country’s defence, and every girl who had a sweetheart should tell men that she would not walk out with him again until he had done his part in licking the Germans.”

The Guardian newspaper chimed in, breathlessly reporting on the activities of the “Order of the White Feather“, hoping that the gesture “would shame every young slacker” into enlisting.

In theory, such an “award” was intended to inspire the dilatory to fulfill his duty to King and country. In practice, such presentations were often mean-spirited and out of line. Sometimes, grotesquely so.

The movement spread across Great Britain and the Commonwealth nations and across Europe, encouraged by suffragettes such as Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughter Christabel, and feminist writers Mary Augusta Ward, founding President of the Women’s National Anti-Suffrage League, and British-Hungarian novelist and playwright, Emma Orczy.

Distributors of the white feather were almost exclusively female, who frequently misjudged their targets. Stories abound of men on leave, wounded, or in reserved occupations being handed one of the odious symbols.

Seaman George Samson received a white feather on the same day he was awarded the British Commonwealth’s highest military award for gallantry in combat, equivalent to the American Medal of Honor: the Victoria Cross.

Seaman George Samson received a white feather on the same day he was awarded the British Commonwealth’s highest military award for gallantry in combat, equivalent to the American Medal of Honor: the Victoria Cross.

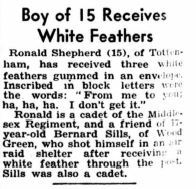

Gangs of “feather girls” took to the streets, looking for military-age men out of uniform. Frederick Broome was fifteen years old, when “accosted by four girls who gave me three white feathers.”

The writer Compton Mackenzie, himself a serving soldier, complained that these “idiotic young women were using white feathers to get rid of boyfriends of whom they were tired“.

James Lovegrove was sixteen when he received his first white feather: “On my way to work one morning a group of women surrounded me. They started shouting and yelling at me, calling me all sorts of names for not being a soldier! Do you know what they did? They struck a white feather in my coat, meaning I was a coward. Oh, I did feel dreadful, so ashamed.” Lovegrove went straight to the recruiting office, who tried to send him home for being too young and too small: “You see, I was five foot six inches and only about eight and a half stone. This time he made me out to be about six feet tall and twelve stone, at least, that is what he wrote down. All lies of course – but I was in!”.

James Lovegrove was sixteen when he received his first white feather: “On my way to work one morning a group of women surrounded me. They started shouting and yelling at me, calling me all sorts of names for not being a soldier! Do you know what they did? They struck a white feather in my coat, meaning I was a coward. Oh, I did feel dreadful, so ashamed.” Lovegrove went straight to the recruiting office, who tried to send him home for being too young and too small: “You see, I was five foot six inches and only about eight and a half stone. This time he made me out to be about six feet tall and twelve stone, at least, that is what he wrote down. All lies of course – but I was in!”.

James Cutmore attempted to volunteer for the British Army in 1914, but was rejected for being near-sighted. By 1916, the war in Europe was consuming men at a rate unprecedented in history. Governments weren’t nearly so picky. A woman gave Cutmore a white feather as he walked home from work. Humiliated, he enlisted the following day. In the 1980s, Cutmore’s grandchild wrote “By that time, they cared nothing for [near-sightedness]. They just wanted a body to stop a shell, which Rifleman James Cutmore duly did in February 1918, dying of his wounds on March 28. My mother was nine, and never got over it. In her last years, in the 1980s, her once fine brain so crippled by dementia that she could not remember the names of her children, she could still remember his dreadful, lingering, useless death. She could still talk of his last leave, when he was so shell-shocked he could hardly speak and my grandmother ironed his uniform every day in the vain hope of killing the lice.”

Some of these people were not to be put off. One man was confronted by an angry woman in a London park, who demanded to know why he wasn’t in uniform. “Because I’m German“, he said. She gave him a feather anyway.

Some of these people were not to be put off. One man was confronted by an angry woman in a London park, who demanded to know why he wasn’t in uniform. “Because I’m German“, he said. She gave him a feather anyway.

Some men had no patience for such nonsense. Private Ernest Atkins was one. Atkins was riding in a train car, when the woman seated behind him presented him with a white feather. Striking her across the face with his pay book, Atkins promised “Certainly I’ll take your feather back to the boys at Passchendaele. I’m in civvies because people think my uniform might be lousy, but if I had it on I wouldn’t be half as lousy as you.”

Private Norman Demuth was discharged from the British Army, after being wounded in 1916. A woman on a bus handed Demuth a feather, saying “Here’s a gift for a brave soldier.” Demuth was cooler than I might have been, under the circumstances: “Thank you very much – I wanted one of those.” He used the feather to clean his pipe, handing it back to her with the comment, “You know we didn’t get these in the trenches.”

Private Norman Demuth was discharged from the British Army, after being wounded in 1916. A woman on a bus handed Demuth a feather, saying “Here’s a gift for a brave soldier.” Demuth was cooler than I might have been, under the circumstances: “Thank you very much – I wanted one of those.” He used the feather to clean his pipe, handing it back to her with the comment, “You know we didn’t get these in the trenches.”

Inevitably, the white feather became a problem, when civilian government employees began to receive the hated symbol. Home Secretary Reginald McKenna issued lapel badges to employees in state industries, reading “King and Country”, proving that they too, were serving the war effort. Veterans who’d been discharged for wounds or illness were likewise issued such a badge, that they not be accosted in the street.

So it was that the laborer from the small town in Germany was sent to kill the greengrocer from St. Albans, spurred on by their women and the whole sorry mess driven by the politicians who would make war. The white feather campaign was briefly revived during WW2, but never caught on to anything approaching the same degree as the first.

The English poet, writer and soldier Siegfried Loraine Sassoon, CBE, MC, was decorated for bravery on the Western Front. Sassoon would become one of the leading poets of WW1. Let him have the final word.

“If I were fierce, and bald, and short of breath,

I’d live with scarlet majors at the Base,

And speed glum heroes up the line to death…

And when the war is done and youth stone dead,

I’d toddle safely home and die – in bed.”

Siegfried Sassoon

London’s teaching hospitals at first explored quiet means of taking down what they regarded as an insult to the profession. By November, medical students were crossing the Thames with sledge hammers and crow bars, intending to take matters into their own hands.

London’s teaching hospitals at first explored quiet means of taking down what they regarded as an insult to the profession. By November, medical students were crossing the Thames with sledge hammers and crow bars, intending to take matters into their own hands. Seventy-five years would come and go, before a new Brown Dog memorial was commissioned by the National Anti-Vivisection Society and the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection.

Seventy-five years would come and go, before a new Brown Dog memorial was commissioned by the National Anti-Vivisection Society and the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection.

The problem was, the Pope refused to grant the divorce. Henry launched the Reformation so that he could divorce his wife and marry this young girl from Kent, getting his divorce the following year and going on to become Supreme Head of the Church of England.

The problem was, the Pope refused to grant the divorce. Henry launched the Reformation so that he could divorce his wife and marry this young girl from Kent, getting his divorce the following year and going on to become Supreme Head of the Church of England. Anne of Cleaves would be wife #4, an arranged marriage with a German Princess intended to secure an alliance with the other major Protestant power on the continent, especially after England’s break with Rome over that first divorce. Henry was put off by her appearance however, apparently believing himself to be quite the prize. The marriage went unconsummated. They were amicably divorced after 6 months.

Anne of Cleaves would be wife #4, an arranged marriage with a German Princess intended to secure an alliance with the other major Protestant power on the continent, especially after England’s break with Rome over that first divorce. Henry was put off by her appearance however, apparently believing himself to be quite the prize. The marriage went unconsummated. They were amicably divorced after 6 months.

When Nazi Germany invaded Poland the following September, London mayor Herbert Morrison was at 10 Downing Street, meeting with Chamberlain’s aide, Sir Horace Wilson. Morrison believed that the time had come for Operation Pied Piper. A year to the day from the Prime Minister’s “Peace in our Time” declaration, Wilson protested. “But we’re not at war yet, and we wouldn’t want to do anything to upset delicate negotiations, would we?”

When Nazi Germany invaded Poland the following September, London mayor Herbert Morrison was at 10 Downing Street, meeting with Chamberlain’s aide, Sir Horace Wilson. Morrison believed that the time had come for Operation Pied Piper. A year to the day from the Prime Minister’s “Peace in our Time” declaration, Wilson protested. “But we’re not at war yet, and we wouldn’t want to do anything to upset delicate negotiations, would we?”

BBC History reported that, “within a week, a quarter of the population of Britain would have a new address”.

BBC History reported that, “within a week, a quarter of the population of Britain would have a new address”. The evacuation of all that humanity ran relatively smoothly, considering. James Roffey, founder of the Evacuees Reunion Association, recalls ‘We marched to Waterloo Station behind our head teacher carrying a banner with our school’s name on it. We all thought it was a holiday, but the only thing we couldn’t work out was why the women and girls were crying.’

The evacuation of all that humanity ran relatively smoothly, considering. James Roffey, founder of the Evacuees Reunion Association, recalls ‘We marched to Waterloo Station behind our head teacher carrying a banner with our school’s name on it. We all thought it was a holiday, but the only thing we couldn’t work out was why the women and girls were crying.’ In the 2003 BBC Radio documentary “Evacuation: The True Story,” clinical psychologist Steve Davis described the worst cases, as “little more than a pedophile’s charter.”

In the 2003 BBC Radio documentary “Evacuation: The True Story,” clinical psychologist Steve Davis described the worst cases, as “little more than a pedophile’s charter.” Authorities produced posters urging parents to leave the kids where they were, and a good thing, too. The Blitz against London itself began on September 7. The city experienced the most devastating attack to-date on December 29, in a blanket fire-bombing that killed almost 3,600 civilians.

Authorities produced posters urging parents to leave the kids where they were, and a good thing, too. The Blitz against London itself began on September 7. The city experienced the most devastating attack to-date on December 29, in a blanket fire-bombing that killed almost 3,600 civilians. By October 1940, the “

By October 1940, the “

In the end, many family ‘reunions’ were as emotionally bruising as the original breakup. Years had come and gone and new relationships had formed. The war had turned biological family members, into all but strangers.

In the end, many family ‘reunions’ were as emotionally bruising as the original breakup. Years had come and gone and new relationships had formed. The war had turned biological family members, into all but strangers.

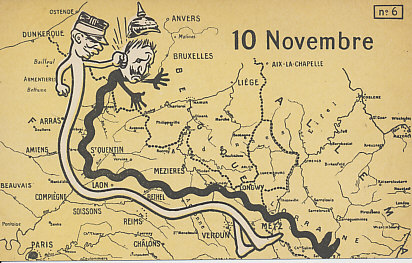

President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation soon after taking office, threatening to blockade southern coastlines. It wasn’t long before the “Anaconda Plan” went into effect, a naval blockade extending 3,500 miles along the Atlantic coastline and Gulf of Mexico, up into the lower Mississippi River.

President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation soon after taking office, threatening to blockade southern coastlines. It wasn’t long before the “Anaconda Plan” went into effect, a naval blockade extending 3,500 miles along the Atlantic coastline and Gulf of Mexico, up into the lower Mississippi River. Cotton would ship out of Mobile, Charleston, Wilmington and other ports, while weapons and other manufactured goods would come back in. Sometimes, these goods would make the whole trans-Atlantic voyage. Often, they would stop at neutral ports in Cuba or the Bahamas.

Cotton would ship out of Mobile, Charleston, Wilmington and other ports, while weapons and other manufactured goods would come back in. Sometimes, these goods would make the whole trans-Atlantic voyage. Often, they would stop at neutral ports in Cuba or the Bahamas.

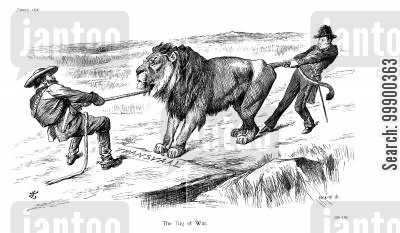

Forty years later and half a world away, what would one day become South Africa was divided into four entities: the two British possessions of Cape Colony and Natal, and the two Boer (Dutch) Republics of the Orange Free State and the South African Republic, better known as Transvaal. Of the four states, Natal and the two Boer Republics were mainly agricultural, populated by subsistence farmers. The Cape Colony was by far the largest, dominating the other three economically, culturally, and socially.

Forty years later and half a world away, what would one day become South Africa was divided into four entities: the two British possessions of Cape Colony and Natal, and the two Boer (Dutch) Republics of the Orange Free State and the South African Republic, better known as Transvaal. Of the four states, Natal and the two Boer Republics were mainly agricultural, populated by subsistence farmers. The Cape Colony was by far the largest, dominating the other three economically, culturally, and socially.

A few tried to replicate the event the following year, but there were explicit orders preventing it. Captain Llewelyn Wyn Griffith recorded that after a night of exchanging carols, dawn on Christmas Day 1915 saw a “rush of men from both sides … [and] a feverish exchange of souvenirs” before the men were quickly called back by their officers.

A few tried to replicate the event the following year, but there were explicit orders preventing it. Captain Llewelyn Wyn Griffith recorded that after a night of exchanging carols, dawn on Christmas Day 1915 saw a “rush of men from both sides … [and] a feverish exchange of souvenirs” before the men were quickly called back by their officers. German soldier Richard Schirrmann wrote in December 1915, “When the Christmas bells sounded in the villages of the Vosges behind the lines …. something fantastically unmilitary occurred. German and French troops spontaneously made peace and ceased hostilities; they visited each other through disused trench tunnels, and exchanged wine, cognac and cigarettes for Westphalian black bread, biscuits and ham. This suited them so well that they remained good friends even after Christmas was over”.

German soldier Richard Schirrmann wrote in December 1915, “When the Christmas bells sounded in the villages of the Vosges behind the lines …. something fantastically unmilitary occurred. German and French troops spontaneously made peace and ceased hostilities; they visited each other through disused trench tunnels, and exchanged wine, cognac and cigarettes for Westphalian black bread, biscuits and ham. This suited them so well that they remained good friends even after Christmas was over”. Even so, there is evidence of a small Christmas truce occurring in 1916, previously unknown to historians. 23-year-old Private Ronald MacKinnon of Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, wrote home about German and Canadian soldiers reaching across battle lines near Arras, sharing Christmas greetings and trading gifts. “I had quite a good Christmas considering I was in the front line”, he wrote. “Christmas Eve was pretty stiff, sentry-go up to the hips in mud of course. … We had a truce on Christmas Day and our German friends were quite friendly. They came over to see us and we traded bully beef for cigars”. The letter ends with Private MacKinnon noting that “Christmas was ‘tray bon’, which means very good.”

Even so, there is evidence of a small Christmas truce occurring in 1916, previously unknown to historians. 23-year-old Private Ronald MacKinnon of Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, wrote home about German and Canadian soldiers reaching across battle lines near Arras, sharing Christmas greetings and trading gifts. “I had quite a good Christmas considering I was in the front line”, he wrote. “Christmas Eve was pretty stiff, sentry-go up to the hips in mud of course. … We had a truce on Christmas Day and our German friends were quite friendly. They came over to see us and we traded bully beef for cigars”. The letter ends with Private MacKinnon noting that “Christmas was ‘tray bon’, which means very good.”

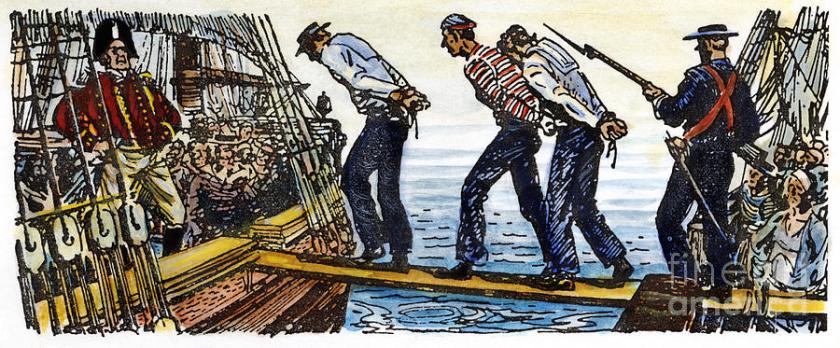

The American public was outraged and there were calls for war in 1807, when HMS Leopard overtook the USS Chesapeake, kidnapping three American-born sailors and one British deserter, leaving another three dead and 18 wounded.

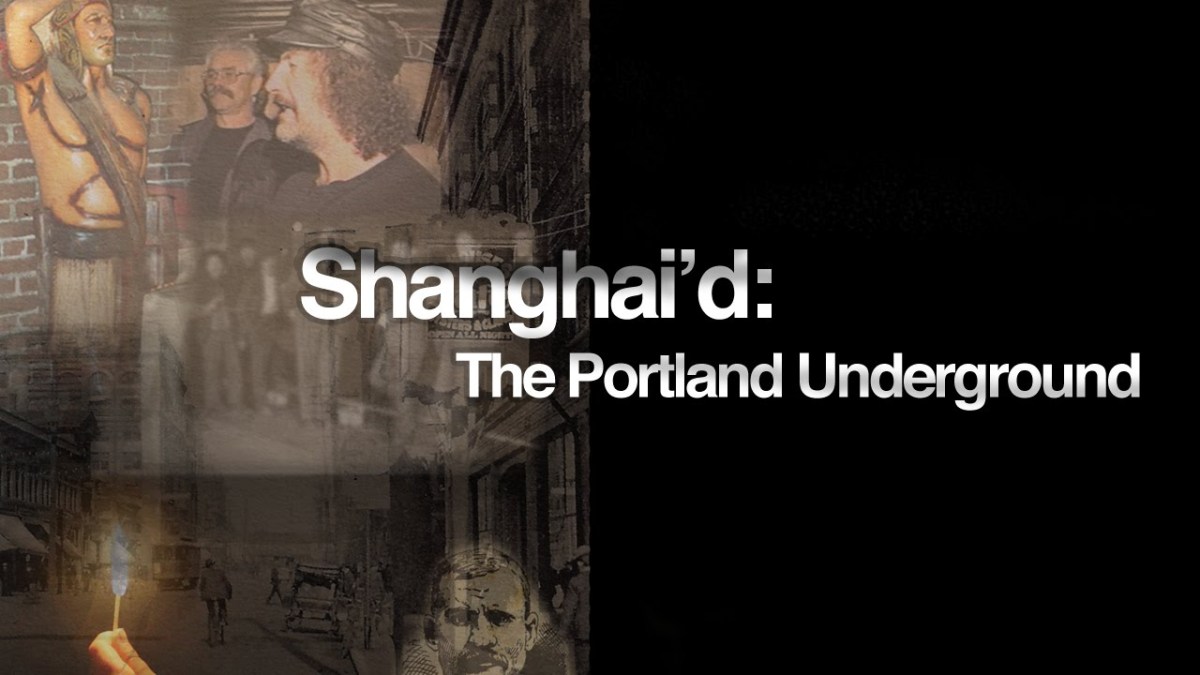

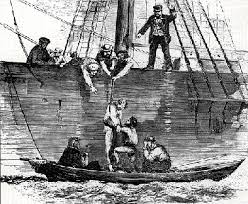

The American public was outraged and there were calls for war in 1807, when HMS Leopard overtook the USS Chesapeake, kidnapping three American-born sailors and one British deserter, leaving another three dead and 18 wounded. Outside of the British Royal Navy, the practice of kidnapping people to serve as shipboard labor was known as “crimping”. Low wages combined with the gold rushes of the 19th century left the waterfront painfully short of manpower, skilled and unskilled, alike. “Boarding Masters” had the job of putting together ship’s crews, and were paid for each recruit. There was strong incentive to produce as many able bodies, as possible. Unwilling men were “shanghaied” by means of trickery, intimidation or violence, most often rendered unconscious and delivered to waiting ships, for a fee.

Outside of the British Royal Navy, the practice of kidnapping people to serve as shipboard labor was known as “crimping”. Low wages combined with the gold rushes of the 19th century left the waterfront painfully short of manpower, skilled and unskilled, alike. “Boarding Masters” had the job of putting together ship’s crews, and were paid for each recruit. There was strong incentive to produce as many able bodies, as possible. Unwilling men were “shanghaied” by means of trickery, intimidation or violence, most often rendered unconscious and delivered to waiting ships, for a fee.

San Francisco political bosses William T. Higgins, (R) and Chris “Blind Boss” Buckley (D) were both notable crimps, and well positioned to look after their political interests. Notorious crimps such as Joseph “Frenchy” Franklin and George Lewis were elected to the California state legislature. There was no better spot, from which to ensure that no legislation would interfere with such a lucrative trade.

San Francisco political bosses William T. Higgins, (R) and Chris “Blind Boss” Buckley (D) were both notable crimps, and well positioned to look after their political interests. Notorious crimps such as Joseph “Frenchy” Franklin and George Lewis were elected to the California state legislature. There was no better spot, from which to ensure that no legislation would interfere with such a lucrative trade. Imagine the hangover the next morning, to wake up and find you’re now at sea, bound for somewhere in the far east. Regulars knew about the trap door and avoided it at all costs, knowing that anyone going over there, was “fair game”.

Imagine the hangover the next morning, to wake up and find you’re now at sea, bound for somewhere in the far east. Regulars knew about the trap door and avoided it at all costs, knowing that anyone going over there, was “fair game”.

In February, Dickens took a train north to the factory town of Lowell, visiting the textile mills and speaking with the “mill girls”, the women who worked there. Once again, he seemed to believe that his native England suffered in the comparison. Dickens spoke of the new buildings and the well dressed, healthy young women who worked in them, no doubt comparing them with the teeming slums and degraded conditions in London.

In February, Dickens took a train north to the factory town of Lowell, visiting the textile mills and speaking with the “mill girls”, the women who worked there. Once again, he seemed to believe that his native England suffered in the comparison. Dickens spoke of the new buildings and the well dressed, healthy young women who worked in them, no doubt comparing them with the teeming slums and degraded conditions in London. Dickens left with a copy of “The Lowell Offering”, a literary magazine written by those same mill girls, which he later described as “four hundred good solid pages, which I have read from beginning to end.”

Dickens left with a copy of “The Lowell Offering”, a literary magazine written by those same mill girls, which he later described as “four hundred good solid pages, which I have read from beginning to end.” The research which followed was published in the form of a thesis, later fleshed out to a full-length book:

The research which followed was published in the form of a thesis, later fleshed out to a full-length book:

You must be logged in to post a comment.