“Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds“.

The line comes from the Bhagavad Gita, the Hindu epic which Mohandas Gandhi described as his “spiritual dictionary”. On July 16, 1945, these words were spoken by J. Robert Oppenheimer, director of the Manhattan Project, as he witnessed “Trinity”, the world’s first nuclear detonation.

The project had begun with a letter from prominent physicists Leo Szilard and Albert Einstein to President Franklin Roosevelt, warning that Nazi Germany may have been working to develop a secret “Super Weapon”. The project ended with the explosion of the “Gadget” in the Jornada del Muerto desert, equaling the explosive force of 20 kilotons of TNT.

The Manhattan Project, the program to develop the Atomic Bomb, was so secret that even Vice President Harry Truman was unaware of its existence.

President Roosevelt passed away on April 14, and Harry Truman was immediately sworn in as President. He was fully briefed on the Manhattan project 10 days later, writing in his diary that night that the US was perfecting an explosive “great enough to destroy the whole world”.

Nazi Germany surrendered on May 7, but the war in the Pacific theater, ground on. By August, Truman faced the most difficult decision ever faced by an American President. Whether to drop an atomic bomb on Imperial Japan.

The morality of President Truman’s decision has been argued ever since. In the end, it was decided that to drop the bomb would end the war faster, with less loss of life on both sides, compared with the invasion of the Japanese home islands.

So it was that the second nuclear detonation in history took place on August 6 over the city of Hiroshima, Japan. “Little Boy”, as the bomb was called, was delivered by the B29 Superfortress “Enola Gay”, named after the mother of United States Army Air Forces pilot Lieutenant Colonel Paul Tibbets. 70,000 Japanese citizens were vaporized in an instant. Another 100,000 later died from injuries and the delayed effects of radiation.

Even then the Japanese Government refused to surrender. ‘Fat Man’, a plutonium bomb carried by the B29 “Bockscar”, was dropped on Nagasaki, on August 9.

The three cities originally considered for this second strike included Kokura, Kyoto and Niigata. Kyoto was withdrawn from consideration due to its religious significance. Niigata was taken out of consideration due to the distance involved.

Kokura was the primary target on this day, but local weather reduced visibility. Bockscar criss-crossed the city for the next 50 minutes, but the bombardier was unable to see well enough to make the drop. Japanese anti-aircraft fire became more intense with every run, and Second Lieutenant Jacob Beser reported activity on the Japanese fighter direction radio bands.

In the end, 393rd Bombardment Squadron Commander Major Charles Sweeney bypassed the city and chose the secondary target, the major shipbuilding center and military port city of Nagasaki.

The 10,000lb, 10’8″ weapon was released at 28,900′. 43 seconds later at an altitude of 1,650′, a perfect circle of 64 detonators exploded inside the heart of the bomb, compacting the plutonium core into a supercritical mass which exploded with the force of 20,000 tons of high explosive.

In the early 1960s, the Nagasaki Prefectural Office put the death count resulting from this day, at 87,000. 70% of the city’s industrial zone was destroyed.

Japan surrendered unconditionally on the 14th of August, ending the most destructive war in history.

Nazi Germany was, in fact, working on a nuclear weapon, and had begun before the allies. They chose to pursue nuclear fusion, colliding atomic particles together to form a new type of nuclear material, instead of fission, the splitting of the atom which resulted in the atomic bomb.

That one critical decision, probably taken in some laboratory or conference room, put Nazi Germany behind in the nuclear arms race. How different would the world be today, had Little Boy and Fat Man had swastikas painted on their sides.

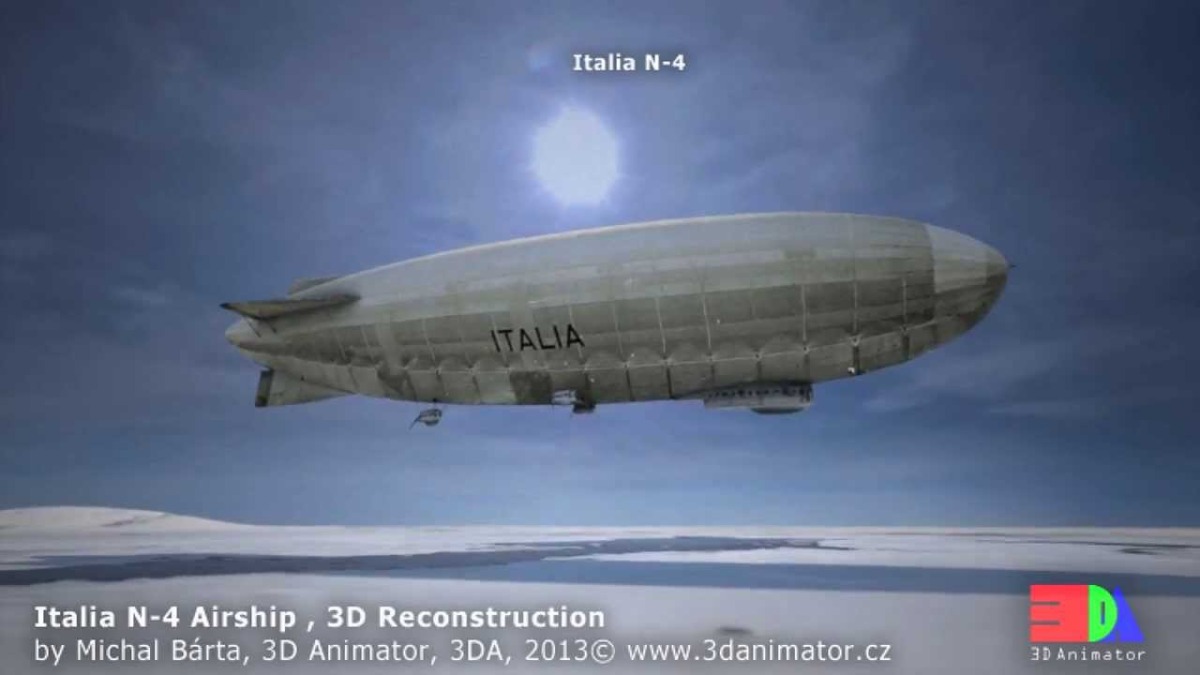

The first of five planned sorties began on May 11, before turning back only eight hours later in near blizzard conditions. The second trip took place in near perfect weather conditions and unlimited visibility, the craft covering 4,000 km (2,500 miles) and setting the stage for the third and final trip departing on May 23.

The first of five planned sorties began on May 11, before turning back only eight hours later in near blizzard conditions. The second trip took place in near perfect weather conditions and unlimited visibility, the craft covering 4,000 km (2,500 miles) and setting the stage for the third and final trip departing on May 23. envelope floated away, Chief Engineer Ettore Arduino started to throw everything he could get his hands on down to the men on the ice. These were the supplies intended for the descent to the pole, but they were now the only thing that stood between life and death. Arduino himself and the rest of the crew drifted away with the now helpless airship.

envelope floated away, Chief Engineer Ettore Arduino started to throw everything he could get his hands on down to the men on the ice. These were the supplies intended for the descent to the pole, but they were now the only thing that stood between life and death. Arduino himself and the rest of the crew drifted away with the now helpless airship.

Escadrille N.124 changed its name in December 1916, adopting that of a French hero of the American Revolution. Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette. Five French officers commanded a core group of 38 American volunteers, supported by all-French mechanics and ground crew. Rounding out the Escadrille were the unit mascots, the African lions Whiskey and Soda.

Escadrille N.124 changed its name in December 1916, adopting that of a French hero of the American Revolution. Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette. Five French officers commanded a core group of 38 American volunteers, supported by all-French mechanics and ground crew. Rounding out the Escadrille were the unit mascots, the African lions Whiskey and Soda.

grounded through the landing line, the ship’s fabric covering became charged in the electrically charged atmosphere, sending a spark to the air frame and igniting a hydrogen leak. Seven million cubic feet of hydrogen ignited almost simultaneously. It was over in less than 40 seconds.

grounded through the landing line, the ship’s fabric covering became charged in the electrically charged atmosphere, sending a spark to the air frame and igniting a hydrogen leak. Seven million cubic feet of hydrogen ignited almost simultaneously. It was over in less than 40 seconds. Where a person was inside the airship, had a lot to do with their chances of survival. Mr and Mrs Hermann Doehner and their three children (Irene, 16, Walter, 10, and Werner, 8) were in the dining room, watching the landing. Mr. Doehner left before the fire broke out. Mrs. Doehner and the two boys were able to jump out, but Irene went looking for her father. Both died in the crash.

Where a person was inside the airship, had a lot to do with their chances of survival. Mr and Mrs Hermann Doehner and their three children (Irene, 16, Walter, 10, and Werner, 8) were in the dining room, watching the landing. Mr. Doehner left before the fire broke out. Mrs. Doehner and the two boys were able to jump out, but Irene went looking for her father. Both died in the crash.

Richthofen chased the rookie Canadian pilot Wilfred “Wop” May behind the lines on April 21, 1918, when he found himself under attack. With a squadron of Sopwith Camels firing from above and anti-aircraft gunners on the ground, he was shot once through the chest with a .303 round, managing to land in a beet field before dying several minutes later. He was still wearing his pajamas, under his flight suit.

Richthofen chased the rookie Canadian pilot Wilfred “Wop” May behind the lines on April 21, 1918, when he found himself under attack. With a squadron of Sopwith Camels firing from above and anti-aircraft gunners on the ground, he was shot once through the chest with a .303 round, managing to land in a beet field before dying several minutes later. He was still wearing his pajamas, under his flight suit.

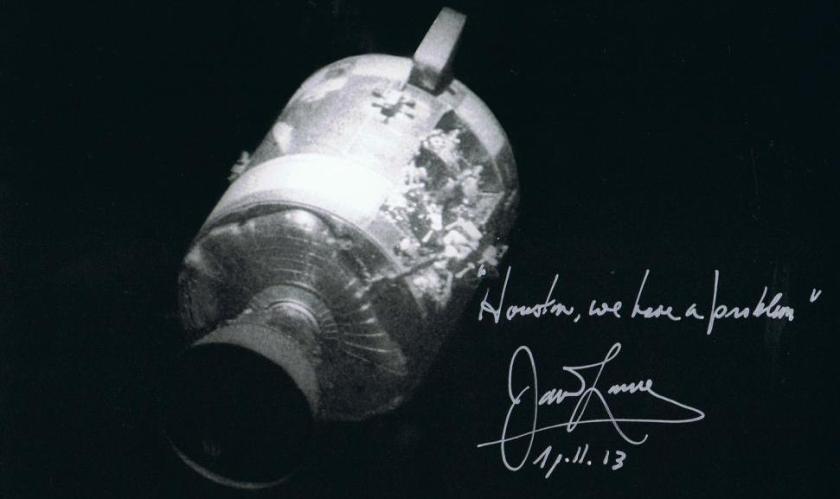

Jack Swigert was supposed to be the backup pilot for the Command Module, (CM), officially joining the Apollo 13 mission only 48 hours earlier, when prime crew member Ken Mattingly was exposed to German measles. Jim Lovell was the world’s most traveled astronaut, a veteran of two Gemini missions and Apollo 8. By launch day, April 11, 1970, Lovell had racked up 572 space flight hours. For Fred Haise, former backup crew member on Apollo 8 and 11, this would be his first spaceflight.

Jack Swigert was supposed to be the backup pilot for the Command Module, (CM), officially joining the Apollo 13 mission only 48 hours earlier, when prime crew member Ken Mattingly was exposed to German measles. Jim Lovell was the world’s most traveled astronaut, a veteran of two Gemini missions and Apollo 8. By launch day, April 11, 1970, Lovell had racked up 572 space flight hours. For Fred Haise, former backup crew member on Apollo 8 and 11, this would be his first spaceflight.

This situation had been suggested during an earlier training simulation, but had been considered unlikely. As it happened, the accident would have been fatal without access to the Lunar Module.

This situation had been suggested during an earlier training simulation, but had been considered unlikely. As it happened, the accident would have been fatal without access to the Lunar Module.

As a test pilot, Reitsch won an Iron Cross, Second Class, for risking her life trying to cut British barrage-balloon cables. On one test flight of the rocket powered Messerschmitt 163 Komet in 1942, she flew the thing at speeds of 500 mph, a speed nearly unheard of at the time. She spun out of control and crash-landed on her 5th flight, leaving her with severe injuries. Her nose was all but torn off, her skull fractured in four places. Two facial bones were broken, and her upper and lower jaws out of alignment. Even then, she managed to write down what had happened before passing out.

As a test pilot, Reitsch won an Iron Cross, Second Class, for risking her life trying to cut British barrage-balloon cables. On one test flight of the rocket powered Messerschmitt 163 Komet in 1942, she flew the thing at speeds of 500 mph, a speed nearly unheard of at the time. She spun out of control and crash-landed on her 5th flight, leaving her with severe injuries. Her nose was all but torn off, her skull fractured in four places. Two facial bones were broken, and her upper and lower jaws out of alignment. Even then, she managed to write down what had happened before passing out. Gold Medal for Military Flying on this day in 1944. Adolf Hitler personally awarded her an Iron Cross, First Class.

Gold Medal for Military Flying on this day in 1944. Adolf Hitler personally awarded her an Iron Cross, First Class.

You must be logged in to post a comment.