Intent on avoiding war with Nazi Germany, Italy, France and Great Britain convened in Munich in September 1938, to resolve German claims on western Czechoslovakia. The “Sudetenland”. Representatives of the Czech and Slovak peoples, were not invited.

For the people of the modern Czech Republic, the Munich agreement was a betrayal. “O nás bez nás!” “About us, without us!”

On September 30, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain returned to London declaring “Peace in Our Time”. The piece of paper Chamberlain held in his hand bore the signatures of Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini and Édouard Daladier as well as his own, annexing enormous swaths of the Sudetenland, to Nazi Germany.

To Winston Churchill, the Munich agreement was an act of appeasement. Feeding the proverbial crocodile (Hitler), in hopes that he will eat you last.

For much of Great Britain, the sense of relief was palpable. In the summer of 1938, the horrors of the Great War were a mere twenty years in the past. Hitler swallowed up Austria only six months earlier as British planners divided the home islands into “risk zones”: “Evacuation,” “Neutral,” and “Reception.”

In some of the most gut wrenching decisions of the age, these people were planning the evacuation of millions of their own children, in the event of war. “Operation Pied Piper”

When Nazi Germany invaded Poland the following September, London Mayor Herbert Morrison was at 10 Downing Street, meeting with Chamberlain’s aide, Sir Horace Wilson. Morrison believed that the time had come for Operation Pied Piper. Only a year to the day from the Prime Minister’s “Peace in our Time” declaration, Wilson protested. “But we’re not at war yet, and we wouldn’t want to do anything to upset delicate negotiations, would we?”

When Nazi Germany invaded Poland the following September, London Mayor Herbert Morrison was at 10 Downing Street, meeting with Chamberlain’s aide, Sir Horace Wilson. Morrison believed that the time had come for Operation Pied Piper. Only a year to the day from the Prime Minister’s “Peace in our Time” declaration, Wilson protested. “But we’re not at war yet, and we wouldn’t want to do anything to upset delicate negotiations, would we?”

Morrison was done with the Prime Minister’s dilatory response to Hitler’s aggression, practically snarling in his thick, East London accent “Look, ’Orace, go in there and tell Neville this from me: If I don’t get the order to evacuate the children from London this morning, I’m going to give it myself – and tell the papers why I’m doing it. ’Ow will ’is nibs like that?”

Thirty minutes later, Morrison had the document. The evacuation, had begun.

This weekend, Superbowl LIV will be played at the Hard Rock Stadium in Miami Gardens Florida, in front of an expected crowd of 65,326. In 1938, forty-five times that number were mobilized in the first four days alone, primarily children, relocated from cities and towns across Great Britain to the relative safety of the countryside.

BBC History reported that, “within a week, a quarter of the population of Britain would have a new address”. Imagine for a moment, what that looked like. What that sounded like.

This was no mindless panic. Zeppelin raids had killed 1,500 civilians in London alone during the ‘Great War’. Since then, governments had become infinitely better at killing each other’s citizens.

This was no mindless panic. Zeppelin raids had killed 1,500 civilians in London alone during the ‘Great War’. Since then, governments had become infinitely better at killing each other’s citizens.

As early as 1922, Prime Minister Lord Arthur Balfour had spoken of ‘unremitting bombardment of a kind that no other city has ever had to endure.’ As many as four million civilian casualties were predicted, in London alone.

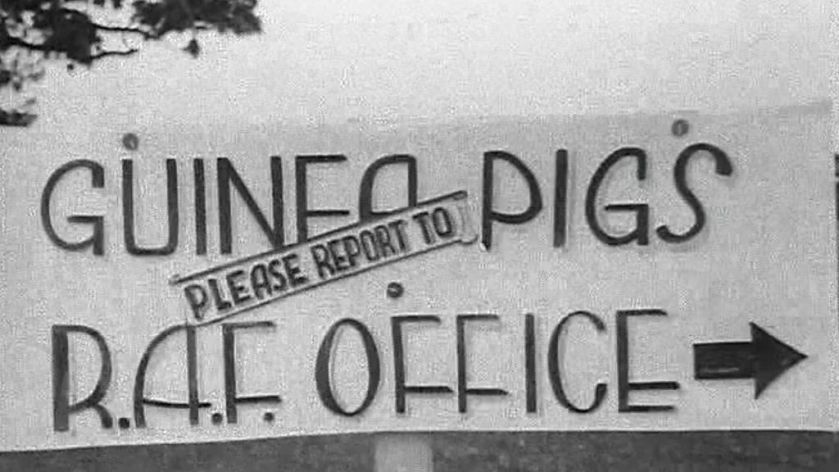

BBC History describes the man in charge of the evacuation, Sir John Anderson, as a “cold, inhuman character with little understanding of the emotional upheaval that might be created by evacuation”.

Children were labeled ‘like luggage’, and sent off with gas masks, toothbrushes and fresh socks & underwear. None of them had the slightest idea of where, or for how long.

All things considered, the evacuation of all that humanity ran relatively smoothly. James Roffey, founder of the Evacuees Reunion Association, recalls ‘We marched to Waterloo Station behind our head teacher carrying a banner with our school’s name on it. We all thought it was a holiday, but the only thing we couldn’t work out was why the women and girls were crying.’

All things considered, the evacuation of all that humanity ran relatively smoothly. James Roffey, founder of the Evacuees Reunion Association, recalls ‘We marched to Waterloo Station behind our head teacher carrying a banner with our school’s name on it. We all thought it was a holiday, but the only thing we couldn’t work out was why the women and girls were crying.’

Arrivals at the billeting areas, were another matter. Many kids were shipped off to the wrong places, and rations were insufficient. Geoffrey Barfoot, billeting officer in the seaside town of Weston-super-Mare, said ‘The trains were coming in thick and fast. It was soon obvious that we just didn’t have the bed space.’

Kids were lined up against walls and on stages, and potential hosts were invited to “take their pick”.

For many, the terrors and confusion of those first few days grew into love and friendships, which lasted a lifetime. Others entered a hell of physical and/or sexual abuse, or worse.

For the first time, “city kids” and country folks were finding out how the “other half” lived, with sometimes amusing results. One boy wrinkled his nose on seeing carrots pulled out of muddy fields, saying “Ours come in tins”. Richard Singleton recalled the first time he asked his Welsh ‘foster mother’ for directions to the toilet. “She took me into a shed and pointed to the ground. Surprised, I asked her for some paper to wipe our bums. She walked away and came back with a bunch of leaves.”

John Abbot, evacuated from Bristol, had his rations stolen by his host family. He was horsewhipped for speaking out while they enjoyed his food while he himself was given nothing more than mashed potatoes. Terri McNeil was locked in a birdcage and left with a piece of bread and a bowl of water.

In the 2003 BBC Radio documentary “Evacuation: The True Story,” clinical psychologist Steve Davis described the worst cases, as “little more than a pedophile’s charter.”

In the 2003 BBC Radio documentary “Evacuation: The True Story,” clinical psychologist Steve Davis described the worst cases, as “little more than a pedophile’s charter.”

Eighty-odd years later, the words “I’ll take that one”, are seared into the memories of more than a few.

Hundreds of evacuees were killed because of relocation, while en route or during stays at “safe havens”. Two boys were killed on a Cornish beach, mined to defend against German amphibious assault.

Apparently, no one had thought to put up a sign.

Irene Wells, age 8, was standing in a church doorway when she was crushed by an army truck. One MP from the house of Commons said “There have been cases of evacuees dying in the evacuation areas. Fancy that type of news coming to the father of children who have been evacuated”.

When German air raids failed to materialize, many parents decided to bring the kids back home. By January 1940, almost half of evacuees had returned.

Authorities produced posters urging parents to leave the kids where they were and a good thing, too. The Blitz against London itself began on September 7. The city experienced the most devastating attack to-date on December 29, in a blanket fire-bombing that killed almost 3,600 civilians.

Authorities produced posters urging parents to leave the kids where they were and a good thing, too. The Blitz against London itself began on September 7. The city experienced the most devastating attack to-date on December 29, in a blanket fire-bombing that killed almost 3,600 civilians.

Sometimes, refugees from relatively safe locations were shipped into high-risk target areas. Hundreds of refugees from Gibraltar were sent into London, in the early days of the Blitz. None of them could have been happy to leave London Station, to see hundreds of locals pushing past them, hurrying to get out.

This story doesn’t only involve the British home islands, either. American Companies like Hoover and Eastman Kodak took thousands of children in, from employees of British subsidiaries. Thousands of English women and children were evacuated to Australia, following the Japanese attack on Singapore.

By October 1940, the “Battle of Britain” had devolved into a mutually devastating battle of attrition in which neither side was capable of striking the death blow. Hitler cast his gaze eastward the following June, with a surprise attack on his “ally”, Josef Stalin.

“Operation Steinbock”, the Luftwaffe’s last large-scale strategic bombing campaign of the war against southern England, was carried out three years later. On this day in 1944, 285 German bombers attacked London in what the Brits called, a “Baby Blitz”.

“Operation Steinbock”, the Luftwaffe’s last large-scale strategic bombing campaign of the war against southern England, was carried out three years later. On this day in 1944, 285 German bombers attacked London in what the Brits called, a “Baby Blitz”.

You’d have to be some tough cookie to call 245 bombers, a Baby Blitz. Late in the war, the subsonic “Doodle Bug” or V1 “flying bomb” was replaced by the terrifying supersonic V2. 1,000 or more of these, the world’s first rocket, were unleashed against southern England, primarily London, killing or wounding 115,000. With a terminal velocity of 2,386mph, you never saw or heard this thing coming, until the weapon had done its work.

Late in the war, the subsonic “Doodle Bug” or V1 “flying bomb” was replaced by the terrifying supersonic V2. 1,000 or more of these, the world’s first rocket, were unleashed against southern England, primarily London, killing or wounding 115,000. With a terminal velocity of 2,386mph, you never saw or heard this thing coming, until the weapon had done its work.

In the end, many family ‘reunions’ were as emotionally bruising as the original breakup. Years had come and gone and new relationships had formed. The war had turned biological family members, into all but strangers.

In the end, many family ‘reunions’ were as emotionally bruising as the original breakup. Years had come and gone and new relationships had formed. The war had turned biological family members, into all but strangers.

Richard Singleton remembers the day his mother came, to take him home to Liverpool. “I had been happily living with ‘Aunty Liz and Uncle Moses’ for four years,” he recalled. “I told Mam that I didn’t want to go home. I was so upset because I was leaving and might never again see aunty and uncle and everything that I loved on the farm.”

Douglas Wood tells a similar story. “During my evacuation I had only seen my mother twice and my father once. On the day that they visited me together, they had walked past me in the street as they did not recognize me. I no longer had a Birmingham accent and this was the subject of much ridicule. I had lost all affinity with my family so there was no love or affection.”

The Austrian-British psychoanalyst Anna Freud, daughter of Sigmund Freud, commissioned an examination of the psychological effects of the separation. After a 12-month study, Freud concluded that “separation from their parents is a worse shock for children than a bombing.”

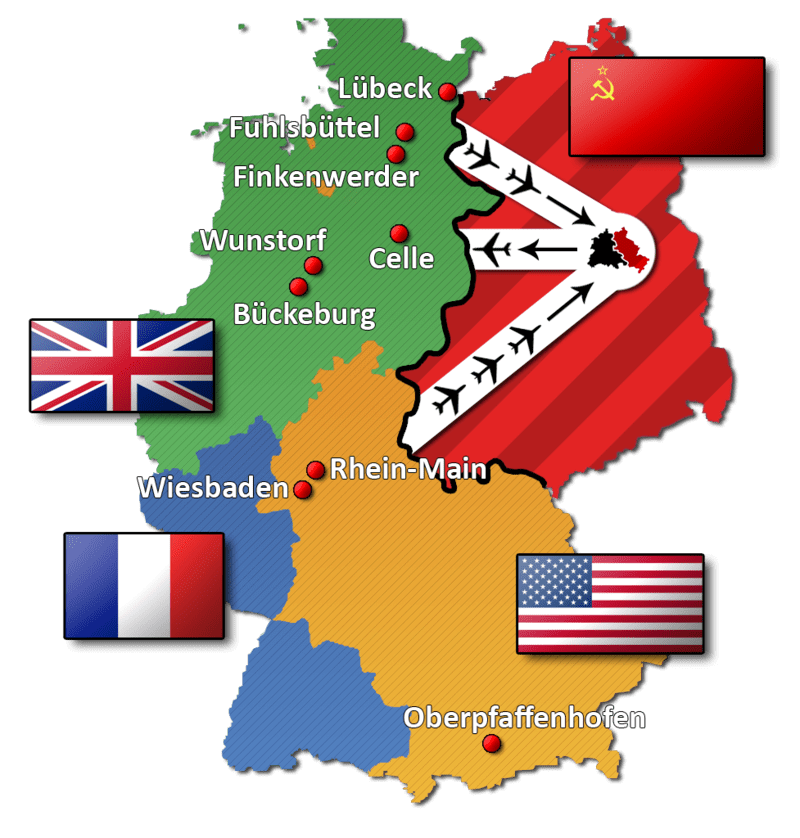

During the war, ideological fault lines were suppressed in the drive to destroy the Nazi war machine. Such differences were quick to reassert themselves in the wake of German defeat. In Soviet-occupied east Germany, factories and equipment were disassembled and transported to the Soviet Union, along with technicians, managers and skilled personnel.

During the war, ideological fault lines were suppressed in the drive to destroy the Nazi war machine. Such differences were quick to reassert themselves in the wake of German defeat. In Soviet-occupied east Germany, factories and equipment were disassembled and transported to the Soviet Union, along with technicians, managers and skilled personnel. West Berlin, a city utterly destroyed by war, was home to some 2.3 million at that time, roughly three times the city of Boston.

West Berlin, a city utterly destroyed by war, was home to some 2.3 million at that time, roughly three times the city of Boston. With that many lives at stake, allied authorities calculated a daily ration of only 1,990 calories would require 646 tons of flour and wheat, 125 tons of cereal, 64 tons of fat, 109 tons of meat and fish, 180 tons of dehydrated potatoes, 180 tons of sugar, 11 tons of coffee, 19 tons of powdered milk, 5 tons of whole milk for the children, 3 tons of fresh yeast for baking, 144 tons of dehydrated vegetables, 38 tons of salt and 10 tons of cheese.

With that many lives at stake, allied authorities calculated a daily ration of only 1,990 calories would require 646 tons of flour and wheat, 125 tons of cereal, 64 tons of fat, 109 tons of meat and fish, 180 tons of dehydrated potatoes, 180 tons of sugar, 11 tons of coffee, 19 tons of powdered milk, 5 tons of whole milk for the children, 3 tons of fresh yeast for baking, 144 tons of dehydrated vegetables, 38 tons of salt and 10 tons of cheese. What followed is known to history, as the

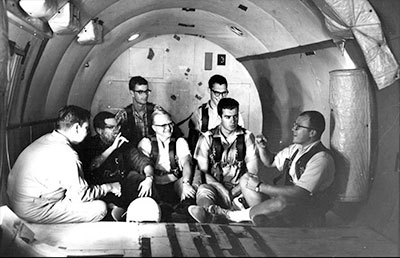

What followed is known to history, as the  US Army Air Force Colonel Gail “Hal” Halvorsen was one of those pilots, flying C-47s and C-54 aircraft deep inside of Soviet controlled territory. On his days off, Halvorsen liked to go sightseeing, often bringing a small movie camera.

US Army Air Force Colonel Gail “Hal” Halvorsen was one of those pilots, flying C-47s and C-54 aircraft deep inside of Soviet controlled territory. On his days off, Halvorsen liked to go sightseeing, often bringing a small movie camera. Newspapers got wind of what was going on. Halvorsen thought he’d be in trouble, but no. Lieutenant General William Henry Tunner liked the idea. A lot. “Operation Little Vittles” became official, on September 22.

Newspapers got wind of what was going on. Halvorsen thought he’d be in trouble, but no. Lieutenant General William Henry Tunner liked the idea. A lot. “Operation Little Vittles” became official, on September 22.

Stripped of armor to increase range and carrying a full load of depth charges, the American anti-submarine bomber with its 10-man crew dove out of the clouds at 1,000 feet, throttles open and machine guns ablaze. The first Condor never came out of that diving turn, while machine gun fire from the second tore into the American bomber, shredding hydraulic systems and setting the right wing ablaze.

Stripped of armor to increase range and carrying a full load of depth charges, the American anti-submarine bomber with its 10-man crew dove out of the clouds at 1,000 feet, throttles open and machine guns ablaze. The first Condor never came out of that diving turn, while machine gun fire from the second tore into the American bomber, shredding hydraulic systems and setting the right wing ablaze. Maxwell had dubbed his B-24 “The Ark”, explaining that “it had a lot of strange animals aboard, and I hoped it would bring us through the deluge”. It must have worked. Seven out of ten crew members lived to be plucked from the water. The second Condor made it back to Bordeaux, where it crashed and burned on landing.

Maxwell had dubbed his B-24 “The Ark”, explaining that “it had a lot of strange animals aboard, and I hoped it would bring us through the deluge”. It must have worked. Seven out of ten crew members lived to be plucked from the water. The second Condor made it back to Bordeaux, where it crashed and burned on landing.

Ed seems to have had life-long problems with alcohol, often resulting in an inability to provide for his family. Amelia must have been a disciplined student despite it all, as she graduated with her high school class, on time, notwithstanding having attended six different schools.

Ed seems to have had life-long problems with alcohol, often resulting in an inability to provide for his family. Amelia must have been a disciplined student despite it all, as she graduated with her high school class, on time, notwithstanding having attended six different schools. Meeley and Pidge worked as nurse’s aids in Toronto, in 1919. There she met several wounded aviators and developed a strong admiration for these people. Amelia would spend much of her free time watching the Royal Flying Corps practice at a nearby airfield.

Meeley and Pidge worked as nurse’s aids in Toronto, in 1919. There she met several wounded aviators and developed a strong admiration for these people. Amelia would spend much of her free time watching the Royal Flying Corps practice at a nearby airfield.

Following the end of the official search, Earhart’s husband and promoter George Palmer Putnam financed private searches of the Phoenix Islands, Christmas (Kiritimati) Island, Fanning (Tabuaeran) Island, the Gilbert and the Marshall Islands, but no trace of the aircraft or its occupants was ever found.

Following the end of the official search, Earhart’s husband and promoter George Palmer Putnam financed private searches of the Phoenix Islands, Christmas (Kiritimati) Island, Fanning (Tabuaeran) Island, the Gilbert and the Marshall Islands, but no trace of the aircraft or its occupants was ever found.

The battered aircraft was completely alone and struggling to maintain altitude. The American pilot was well inside German air space when he looked to his left and saw his worst nightmare. Three feet from his wing tip was the sleek gray shape of a German fighter, the pilot so close that the two men were looking into each other’s eyes. Brown’s co-pilot, Spencer “Pinky” Luke said “My God, this is a nightmare.” “He’s going to destroy us,” was Brown’s reply. This had been his first mission. He was sure it was about to be his last.

The battered aircraft was completely alone and struggling to maintain altitude. The American pilot was well inside German air space when he looked to his left and saw his worst nightmare. Three feet from his wing tip was the sleek gray shape of a German fighter, the pilot so close that the two men were looking into each other’s eyes. Brown’s co-pilot, Spencer “Pinky” Luke said “My God, this is a nightmare.” “He’s going to destroy us,” was Brown’s reply. This had been his first mission. He was sure it was about to be his last. The German had to do something. Nazi leadership would surely shoot him for treason if he was seen this close without completing the kill. One of the American crew was making his way to a gun turret as the German made his decision. Stigler saluted his adversary, motioned with his hand for the stricken B17 to continue, and peeled away.

The German had to do something. Nazi leadership would surely shoot him for treason if he was seen this close without completing the kill. One of the American crew was making his way to a gun turret as the German made his decision. Stigler saluted his adversary, motioned with his hand for the stricken B17 to continue, and peeled away. Over 40 years later, the German pilot was living in Vancouver, Canada. Brown took out an ad in a fighter pilots’ newsletter, explaining that he was searching for the man ‘who saved my life on December 20, 1943.’ Stigler saw the ad, and the two met for the first time in 1987. “It was like meeting a family member”, Brown said of that first meeting. “Like a brother you haven’t seen for 40 years”.

Over 40 years later, the German pilot was living in Vancouver, Canada. Brown took out an ad in a fighter pilots’ newsletter, explaining that he was searching for the man ‘who saved my life on December 20, 1943.’ Stigler saw the ad, and the two met for the first time in 1987. “It was like meeting a family member”, Brown said of that first meeting. “Like a brother you haven’t seen for 40 years”. The two former enemies passed the last two decades of their lives as close friends and occasional fishing buddies.

The two former enemies passed the last two decades of their lives as close friends and occasional fishing buddies.

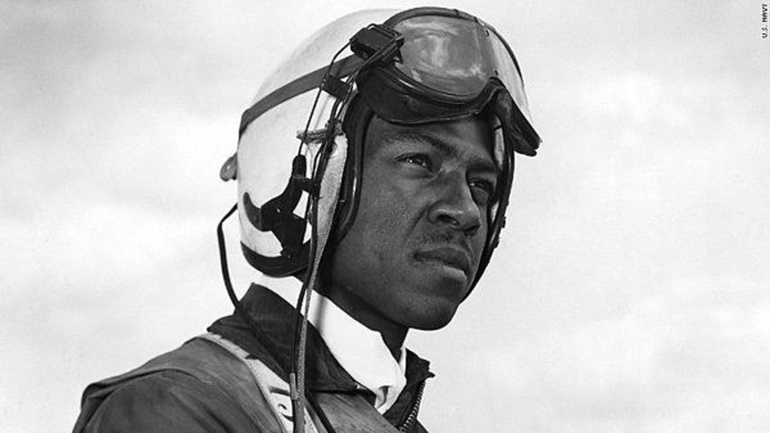

Hudner acted on instinct, deliberately crash landing his own aircraft and, now injured, running across the snow to the aid of his friend and wing man. Hudner scooped snow onto the fire with his bare hands in the bitter 15° cold, burning himself in the progress while Brown faded in and out of consciousness. Soon, a Marine Corps helicopter pilot landed, to help out. The two tore into the stricken aircraft with an axe for 45 minutes, but could not free the trapped pilot.

Hudner acted on instinct, deliberately crash landing his own aircraft and, now injured, running across the snow to the aid of his friend and wing man. Hudner scooped snow onto the fire with his bare hands in the bitter 15° cold, burning himself in the progress while Brown faded in and out of consciousness. Soon, a Marine Corps helicopter pilot landed, to help out. The two tore into the stricken aircraft with an axe for 45 minutes, but could not free the trapped pilot.

The Municipal Airport in Portsmouth New Hampshire opened in the 1930s, expanding in 1951 to become a Strategic Air Command (SAC) base. The name was changed to Pease Air Force Base in 1957, in honor of Harl Pease, Jr., recipient of the Medal of Honor and Distinguished Flying Cross for heroism that led to his death in World War II.

The Municipal Airport in Portsmouth New Hampshire opened in the 1930s, expanding in 1951 to become a Strategic Air Command (SAC) base. The name was changed to Pease Air Force Base in 1957, in honor of Harl Pease, Jr., recipient of the Medal of Honor and Distinguished Flying Cross for heroism that led to his death in World War II. United States Army Air Corps Captain Harl Pease, Jr. was ordered to lead three battered B-17 Flying Fortresses to Del Monte field in Mindanao, to evacuate General Douglas MacArthur, his family and staff, to Australia. One of the aircraft was forced to abort early, while the other developed engine trouble and crashed. Pease alone was able to land his Fortress, despite inoperative wheel brakes and used ration tins covering bullet holes.

United States Army Air Corps Captain Harl Pease, Jr. was ordered to lead three battered B-17 Flying Fortresses to Del Monte field in Mindanao, to evacuate General Douglas MacArthur, his family and staff, to Australia. One of the aircraft was forced to abort early, while the other developed engine trouble and crashed. Pease alone was able to land his Fortress, despite inoperative wheel brakes and used ration tins covering bullet holes. “When 1 engine of the bombardment airplane of which he was pilot failed during a bombing mission over New Guinea, Capt. Pease was forced to return to a base in Australia. Knowing that all available airplanes of his group were to participate the next day in an attack on an enemy-held airdrome near Rabaul, New Britain, although he was not scheduled to take part in this mission, Capt. Pease selected the most serviceable airplane at this base and prepared it for combat, knowing that it had been found and declared unserviceable for combat missions. With the members of his combat crew, who volunteered to accompany him, he rejoined his squadron at Port Moresby, New Guinea, at 1 a.m. on 7 August, after having flown almost continuously since early the preceding morning. With only 3 hours’ rest, he took off with his squadron for the attack. Throughout the long flight to Rabaul, New Britain, he managed by skillful flying of his unserviceable airplane to maintain his position in the group. When the formation was intercepted by about 30 enemy fighter airplanes before reaching the target, Capt. Pease, on the wing which bore the brunt of the hostile attack, by gallant action and the accurate shooting by his crew, succeeded in destroying several Zeros before dropping his bombs on the hostile base as planned, this in spite of continuous enemy attacks. The fight with the enemy pursuit lasted 25 minutes until the group dived into cloud cover. After leaving the target, Capt. Pease’s aircraft fell behind the balance of the group due to unknown difficulties as a result of the combat, and was unable to reach this cover before the enemy pursuit succeeded in igniting 1 of his bomb bay tanks. He was seen to drop the flaming tank. It is believed that Capt. Pease’s airplane and crew were subsequently shot down in flames, as they did not return to their base. In voluntarily performing this mission Capt. Pease contributed materially to the success of the group, and displayed high devotion to duty, valor, and complete contempt for personal danger. His undaunted bravery has been a great inspiration to the officers and men of his unit”.

“When 1 engine of the bombardment airplane of which he was pilot failed during a bombing mission over New Guinea, Capt. Pease was forced to return to a base in Australia. Knowing that all available airplanes of his group were to participate the next day in an attack on an enemy-held airdrome near Rabaul, New Britain, although he was not scheduled to take part in this mission, Capt. Pease selected the most serviceable airplane at this base and prepared it for combat, knowing that it had been found and declared unserviceable for combat missions. With the members of his combat crew, who volunteered to accompany him, he rejoined his squadron at Port Moresby, New Guinea, at 1 a.m. on 7 August, after having flown almost continuously since early the preceding morning. With only 3 hours’ rest, he took off with his squadron for the attack. Throughout the long flight to Rabaul, New Britain, he managed by skillful flying of his unserviceable airplane to maintain his position in the group. When the formation was intercepted by about 30 enemy fighter airplanes before reaching the target, Capt. Pease, on the wing which bore the brunt of the hostile attack, by gallant action and the accurate shooting by his crew, succeeded in destroying several Zeros before dropping his bombs on the hostile base as planned, this in spite of continuous enemy attacks. The fight with the enemy pursuit lasted 25 minutes until the group dived into cloud cover. After leaving the target, Capt. Pease’s aircraft fell behind the balance of the group due to unknown difficulties as a result of the combat, and was unable to reach this cover before the enemy pursuit succeeded in igniting 1 of his bomb bay tanks. He was seen to drop the flaming tank. It is believed that Capt. Pease’s airplane and crew were subsequently shot down in flames, as they did not return to their base. In voluntarily performing this mission Capt. Pease contributed materially to the success of the group, and displayed high devotion to duty, valor, and complete contempt for personal danger. His undaunted bravery has been a great inspiration to the officers and men of his unit”.

You must be logged in to post a comment.