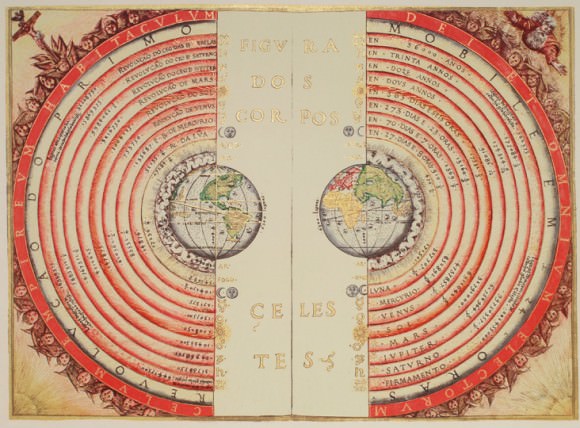

Planet Earth exists at the center of the solar system, the sun and other celestial bodies revolving around it. That was the “geocentric” model of the solar system, from the time of antiquity.

The perspective was by no means unanimous. The Greek astronomer and mathematician Aristarchus of Samos put the Sun in the center of the universe, in the third century BC. Later Greek astronomers Hipparchus and Ptolemy agreed, refining Aristarchus’ methods to arrive at a fairly accurate estimate for the distance to the moon, but theirs remained the minority view.

In the 15th century, Polish mathematician and astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus parted ways with the orthodoxy of his time, describing a “heliocentric” model of the universe placing the sun at the center. The Earth and other bodies, according to this model, revolved around the sun.

Copernicus resisted publishing his ideas until the end of his life, fearing to offend the religious sensibilities of the time. Legend has it that he was presented with an advance copy of his “De revolutionibus orbium coelestium” (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres) as he awakened on his death bed from a stroke-induced coma. He took one look at his book, closed his eyes, and never opened them again.

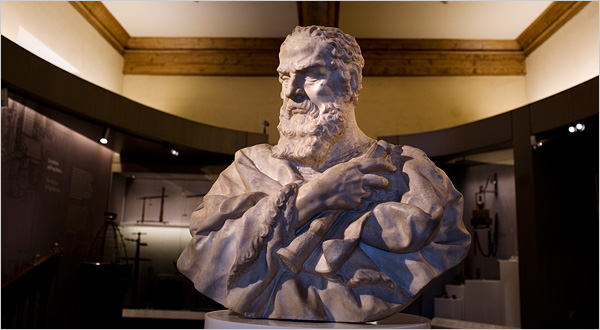

The Italian physicist, mathematician, and astronomer Galileo Galilei came along, about a hundred years later. Galileo has been called the “Father of Modern Observational Astronomy”, his improvements to the telescope and resulting astronomical observations supporting the Copernican heliocentric view.

They also brought him to the attention of the Roman Inquisition.

Biblical references such as, “The Lord set the Earth on its Foundations; it can Never be Moved.” (Psalm 104:5) and “And the Sun Rises and Sets and Returns to its Place.” (Ecclesiastes 1:5) were taken at the time as literal and immutable fact, becoming the basis for religious objection to the heliocentric model.

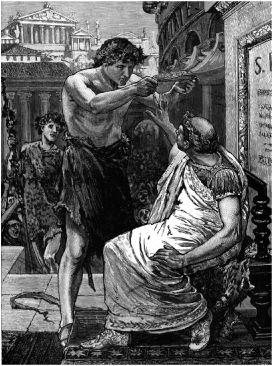

Galileo was brought before inquisitor Vincenzo Maculani for trial in 1633. The astronomer backpedaled before the Inquisition, but only to a point, testifying in his fourth deposition on this day in 1633, that “I do not hold this opinion of Copernicus, and I have not held it after being ordered by injunction to abandon it. For the rest, here I am in your hands; do as you please”.

There is a story about Galileo, which may or may not be true. After his conviction, the astronomer is said to have muttered “Eppur si muove” — “And yet it moves”.

The Inquisition condemned the astronomer to “abjure, curse, & detest” his Copernican heliocentric views, returning him to house arrest at his villa in 1634, there to spend the rest of his life. Galileo Galilei, the Italian polymath who all but orchestrated the transition from late middle ages to scientific Renaissance, died on January 8, 1642, desiring to be buried in the main body of the Basilica of Santa Croce, next to the tombs of his father and ancestors. His final wishes were ignored at the time, though they would be honored some ninety-five years later, when Galileo was re-interred in the basilica, in 1737.

Often, atmospheric conditions in these burial vaults lead to a natural mummification of the corpse. Sometimes, they look almost lifelike. When it came to the saints, believers took this to be proof of the incorruptibility of these individuals, and small body parts were taken as holy relics.

Such a custom seems ghoulish to us today, but the practice was was quite old by the 18th century. Galileo is not now and never was a Saint of the Catholic church, quite the opposite. The Inquisition had judged the man an enemy of the church, a heretic.

Possibly, the condition of Galileo’s body made him appear thus “incorruptible”. Be that as it may, Anton Francesco Gori removed the thumb, index and middle fingers on March 12, 1737, the digits with which Galileo wrote down his theories of the cosmos. The digits with which he adjusted his telescope.

The other two fingers and a tooth disappeared in 1905, leaving the middle finger from Galileo’s right hand on exhibit at the Museo Galileo in Florence, Italy. Locked in a glass case, the finger points upward, toward the sky.

Some 100 years later, two fingers and a tooth were purchased at auction, and have since rejoined their fellow digit at the Museo Galileo. To this day, these remain the only human body parts, in a museum otherwise devoted to scientific instrumentation.

Some 100 years later, two fingers and a tooth were purchased at auction, and have since rejoined their fellow digit at the Museo Galileo. To this day, these remain the only human body parts, in a museum otherwise devoted to scientific instrumentation.

Nearly four-hundred years after his death, Galileo’s extremity points upward, toward the glory of the cosmos. Either that, or the finger rises in eternal defiance, flipping the bird to the church which had condemned him.

Indigenous nations of the time divided more along ethnic and linguistic rather than political lines, so there was no monolithic policy among the tribes. At least one British fort was taken with profuse apologies by the Indians, who explained that it was the other nations making them do it.

Indigenous nations of the time divided more along ethnic and linguistic rather than political lines, so there was no monolithic policy among the tribes. At least one British fort was taken with profuse apologies by the Indians, who explained that it was the other nations making them do it.

Some sixty to eighty Ohio valley Indians died of the disease following the Fort Pitt episode, but the outbreak appears isolated. Meanwhile, Indian warriors had looted clothing from some 2,000 outlying settlers they had killed or abducted.

Some sixty to eighty Ohio valley Indians died of the disease following the Fort Pitt episode, but the outbreak appears isolated. Meanwhile, Indian warriors had looted clothing from some 2,000 outlying settlers they had killed or abducted.

The British Royal Proclamation of October 7, 1763, drew a line between the British colonies and Indian lands, creating a vast Indian Reserve stretching from the Appalachians to the Mississippi River and from Florida to Newfoundland. For the Indian Nations, this was the first time that a multi-tribal effort had been launched against British expansion, the first time such an effort had not ended in defeat.

The British Royal Proclamation of October 7, 1763, drew a line between the British colonies and Indian lands, creating a vast Indian Reserve stretching from the Appalachians to the Mississippi River and from Florida to Newfoundland. For the Indian Nations, this was the first time that a multi-tribal effort had been launched against British expansion, the first time such an effort had not ended in defeat.

Later discovered by Faustulus, the boys were reared by the shepherd and his wife. Much later, the twins became leaders of a band of young shepherd warriors. On learning their true identity, the twins attacked Alba Longa, killed King Amulius, and restored their grandfather to the throne.

Later discovered by Faustulus, the boys were reared by the shepherd and his wife. Much later, the twins became leaders of a band of young shepherd warriors. On learning their true identity, the twins attacked Alba Longa, killed King Amulius, and restored their grandfather to the throne.

Finally, even John D. Rockefeller, Jr., a lifelong teetotaler who contributed $350,000 to the Anti-Saloon League, had to announce his support for repeal.

Finally, even John D. Rockefeller, Jr., a lifelong teetotaler who contributed $350,000 to the Anti-Saloon League, had to announce his support for repeal.

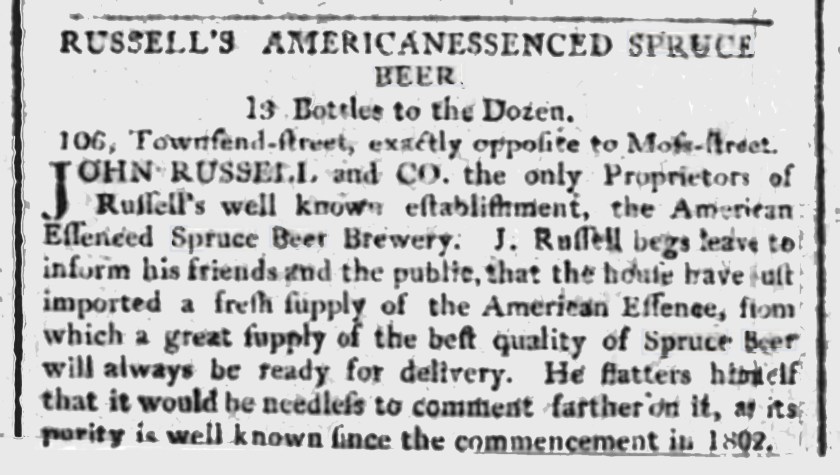

The night before Roosevelt’s law went into effect, April 6, 1933, beer lovers lined up at the doors of their favorite public houses, waiting for their first legal beer in thirteen years. A million and a half barrels of the stuff were consumed the following day, a date remembered today as “National Beer Day”.

The night before Roosevelt’s law went into effect, April 6, 1933, beer lovers lined up at the doors of their favorite public houses, waiting for their first legal beer in thirteen years. A million and a half barrels of the stuff were consumed the following day, a date remembered today as “National Beer Day”.

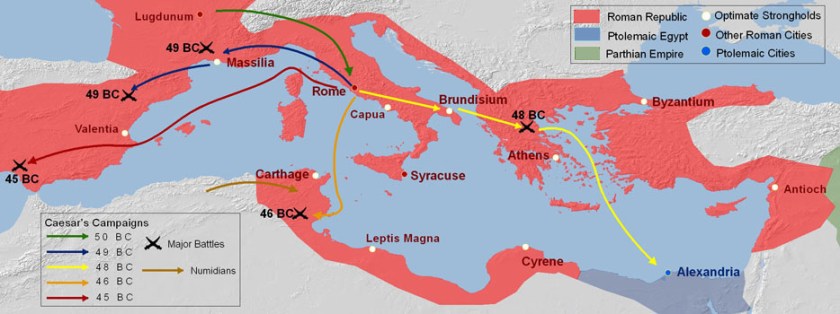

Caesar rose through the ranks, organizing a coalition of three to rule the Republic. It was the first such “Triumvirate”, combining the popular general Pompey “The Great”, Crassus, the wealthiest man in all of Rome, and the rising young general and politician, Julius Caesar himself.

Caesar rose through the ranks, organizing a coalition of three to rule the Republic. It was the first such “Triumvirate”, combining the popular general Pompey “The Great”, Crassus, the wealthiest man in all of Rome, and the rising young general and politician, Julius Caesar himself.

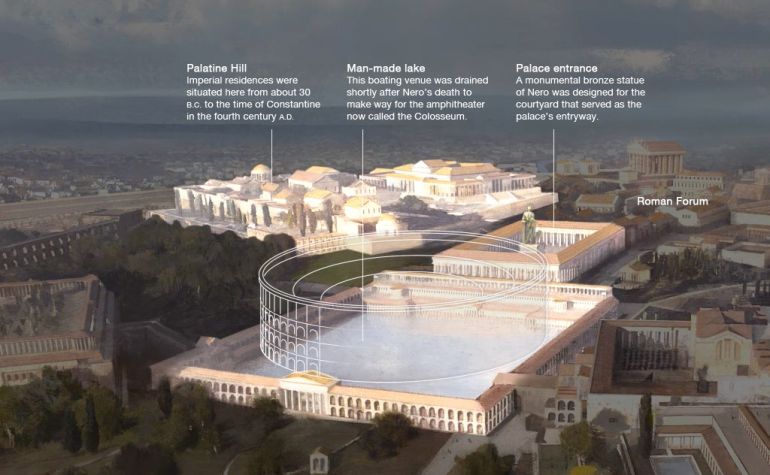

Be that as it may, three things are certain. First, The fire burned for six days, utterly destroying three of the 14 districts of Rome, and severely damaging seven others. Next, Nero used the excuse of the fire to go after the Christians, having many of them arrested and executed. Last, the Domus Aurea (“Golden Palace”) and surrounding “Pleasure Gardens” which the emperor built on the ruins, would be the death of Emperor Nero.

Be that as it may, three things are certain. First, The fire burned for six days, utterly destroying three of the 14 districts of Rome, and severely damaging seven others. Next, Nero used the excuse of the fire to go after the Christians, having many of them arrested and executed. Last, the Domus Aurea (“Golden Palace”) and surrounding “Pleasure Gardens” which the emperor built on the ruins, would be the death of Emperor Nero.

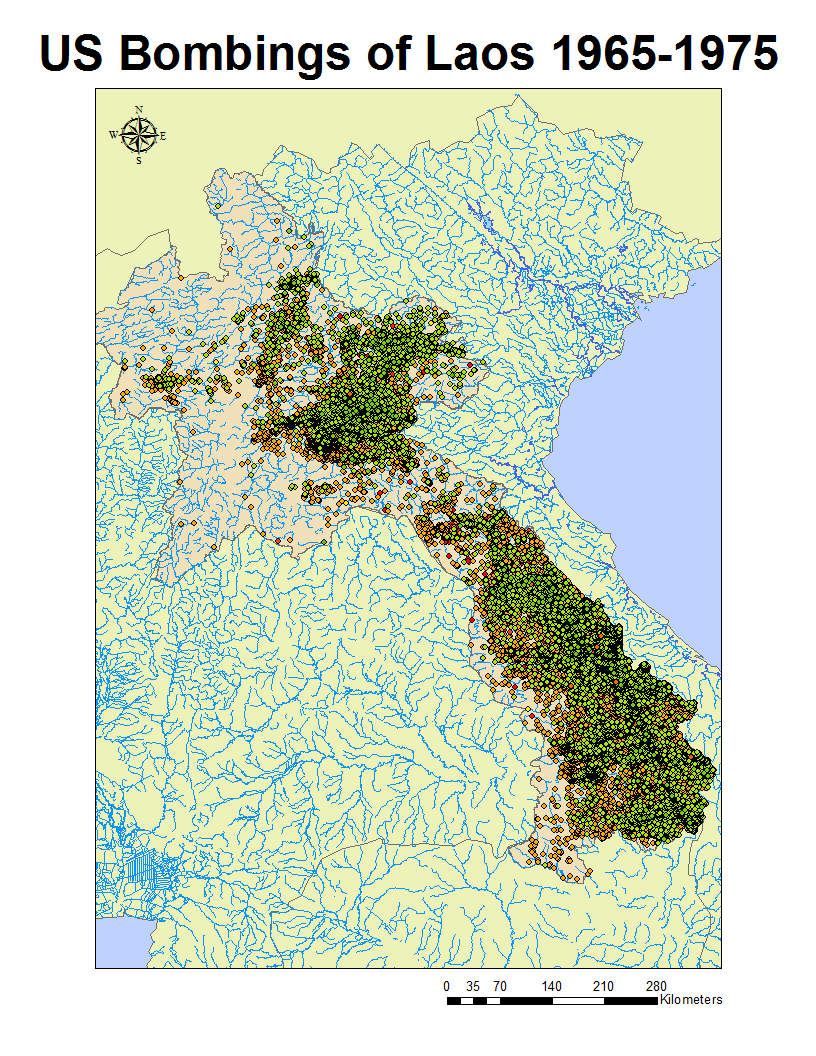

The Geneva Convention of 1954 partitioned Vietnam at the 17th parallel, and guaranteed Laotian neutrality. North Vietnamese communists had no intention of withdrawing from the country or abandoning their Laotian communist allies, any more than they were going to abandon the drive for military reunification, with the south.

The Geneva Convention of 1954 partitioned Vietnam at the 17th parallel, and guaranteed Laotian neutrality. North Vietnamese communists had no intention of withdrawing from the country or abandoning their Laotian communist allies, any more than they were going to abandon the drive for military reunification, with the south.

On February 18, 1977, Murray Hiebert, now senior associate of the Southeast Asia Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C. summed up the situation in a letter to the Mennonite Central Committee, US: “…a formerly prosperous people still stunned and demoralized by the destruction of their villages, the annihilation of their livestock, the cratering of their fields, and the realization that every stroke of their hoes is potentially fatal.”

On February 18, 1977, Murray Hiebert, now senior associate of the Southeast Asia Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C. summed up the situation in a letter to the Mennonite Central Committee, US: “…a formerly prosperous people still stunned and demoralized by the destruction of their villages, the annihilation of their livestock, the cratering of their fields, and the realization that every stroke of their hoes is potentially fatal.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.