The American Revolution began with the “Shot Heard Round the World” on the morning of April 19, 1775. Within days of the Battles at Lexington and Concord and the subsequent British withdrawal to Boston, over 20,000 men poured into Cambridge from all over New England. Abandoned Tory homes and the empty Christ Church became temporary barracks and field hospitals. Even Harvard College shut down, its buildings becoming quarters for at least 1,600 Patriots.

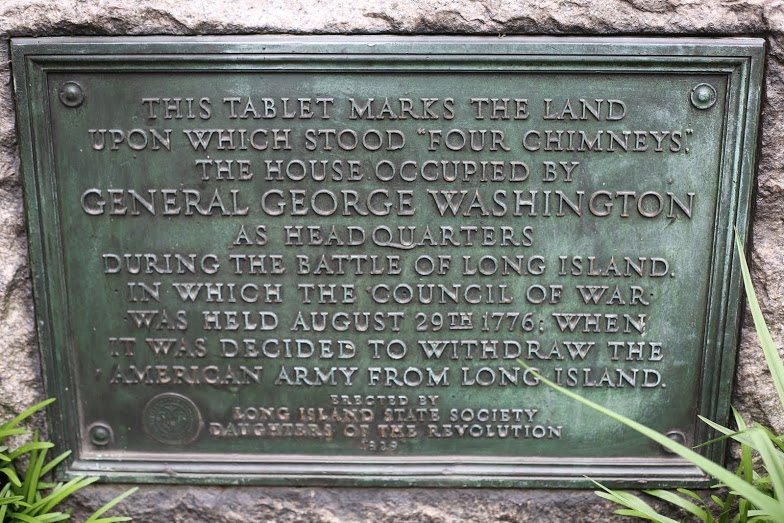

The Continental Congress appointed George Washington General of this “Army” on June 15, two days before the British assault on Farmer Breed’s hill. An action which took its name from that of a neighboring farmer, going into history as the Battle of Bunker Hill.

The Continental Congress appointed George Washington General of this “Army” on June 15, two days before the British assault on Farmer Breed’s hill. An action which took its name from that of a neighboring farmer, going into history as the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Shortly after his arrival in July, General Washington discovered that his army had enough gunpowder for nine rounds per man, and then they’d be done.

At the time, Boston was a virtual island, connected to the mainland by a narrow strip of land. British forces were effectively penned up in Boston, by a force too weak to do anything about it.

The stalemate dragged on for months, when a 25-year-old bookseller came to General Washington with a plan. His name was Henry Knox. His plan was a 300-mile, round trip slog into a New England winter, to retrieve the guns of Fort Ticonderoga.

Washington’s advisors derided the idea as hopeless, but the General approved. Henry Knox set out with a column of men on December 1.

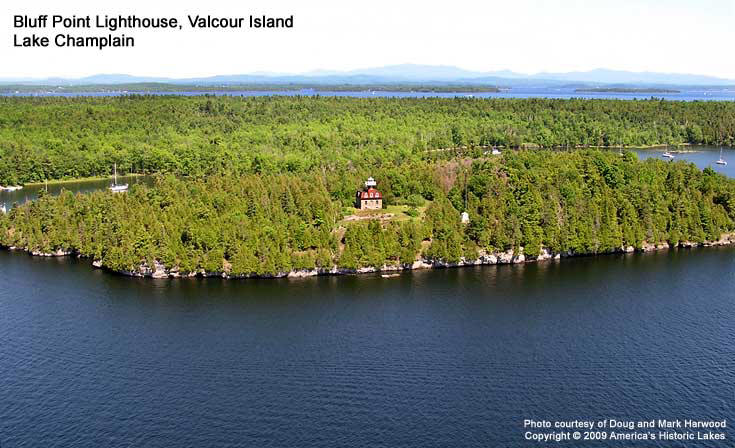

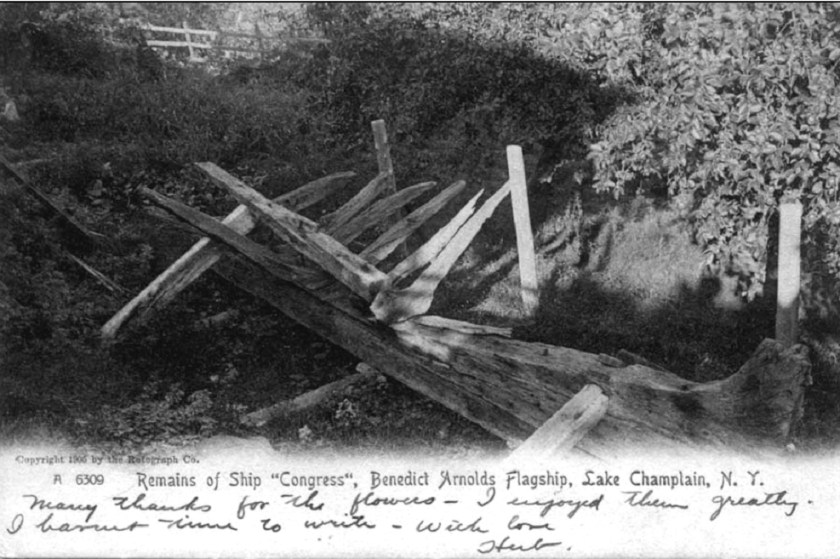

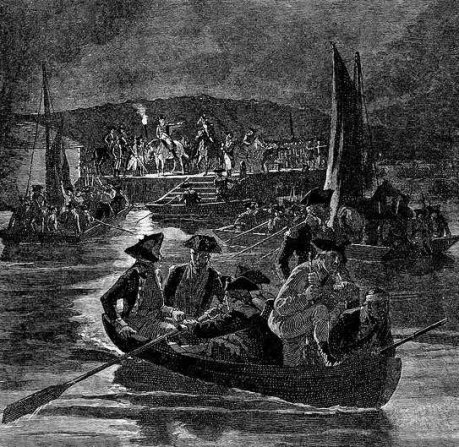

Located on the New York banks of Lake Champlain, Fort Ticonderoga was captured by a small force led by Ethan Allen and Colonel Benedict Arnold, in May of that year. In it were brass and iron cannon, howitzers, and mortars, 59 pieces in all. Arriving on December 5, Knox and his men set about disassembling the artillery, making it ready for transport. A flotilla of flat bottom boats was scavenged from all over the countryside, the guns loaded and rowed the length of Lake George, arriving barely before the water began to freeze over.

Local farmers were enlisted to help and by December 17, Knox was able to report to General Washington “I have had made forty two exceedingly strong sleds & have provided eighty yoke of oxen to drag them as far as Springfield where I shall get fresh cattle to carry them to camp. . . . I hope in 16 or 17 days to be able to present your Excellency a noble train of artillery.”

Bare ground prevented the sleds from moving until Christmas morning, when a heavy snow fell and the column set out for Albany. Two attempts to cross the Hudson River on January 5 each resulted in cannon being lost to the river, but finally Knox was able to write “Went on the ice about 8 o’clock in the morning & proceeded so carefully that before night we got over 23 sleds & were so lucky as to get the Cannon out of the River, owing to the assistance the good people of the City of Albany gave.”

Continuing east, Knox and his men crossed into Massachusetts, over the Berkshires, and on to Springfield. With 80 fresh yoke of oxen, the 5,400lb sleds moved along much of what are modern-day Routes 9 and 20, passing through Brookfield, Spencer, Leicester, Worcester, Shrewsbury, Northborough, Marlborough, Southborough, Framingham, Wayland, Weston, Waltham, and Watertown.

It must have been a sight when that noble train of artillery entered Cambridge on this day in 1776. By March, Henry Knox’ cannon would be manhandled to the top of Dorchester Heights, resulting in the British evacuation of Boston and a peculiar Massachusetts institution which exists to this day, known as “Evacuation Day”: March 17.

It is doubtful whether Washington possessed sufficient powder or shot for a sustained campaign, but British forces occupying Boston didn’t know that. The mere presence of those guns moved British General Howe to weigh anchor and sail for Nova Scotia, but that must be a story for another day.

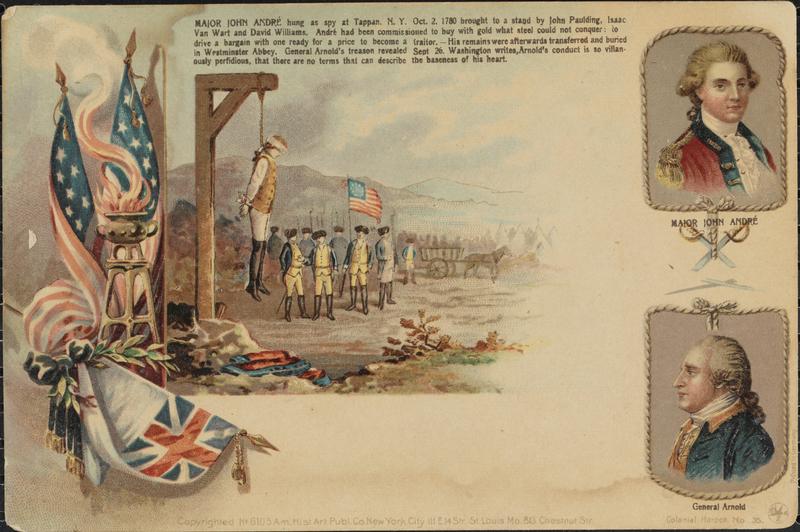

A “Fidelity Medallion” was awarded to three militia men in 1780, for the capture of

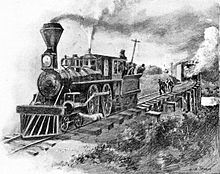

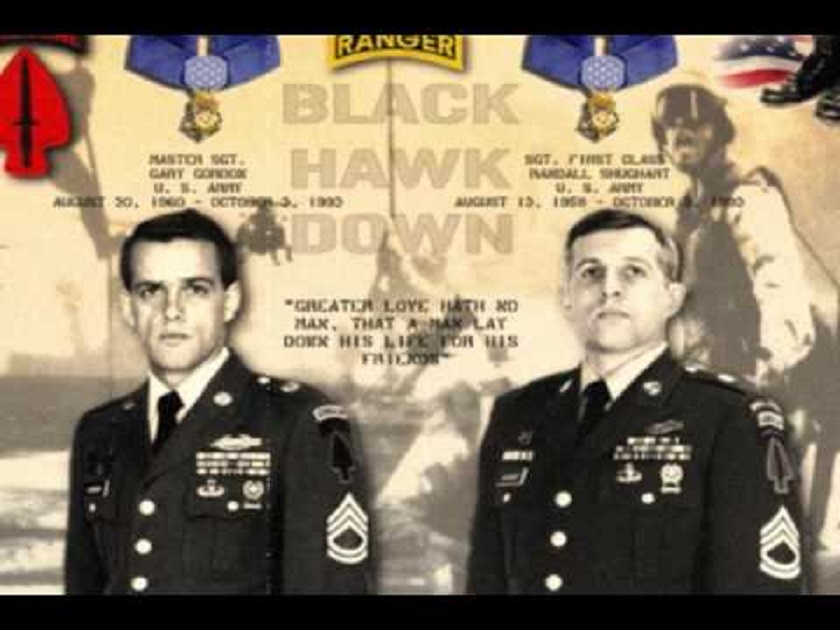

A “Fidelity Medallion” was awarded to three militia men in 1780, for the capture of  An Army version of the medal was created the following July, first awarded to six Union soldiers for hijacking the Confederate locomotive, “The General”. Leader of the raid James Andrews was caught and hanged as a Union spy. He alone was judged ineligible for the medal of honor, as he was a civilian.

An Army version of the medal was created the following July, first awarded to six Union soldiers for hijacking the Confederate locomotive, “The General”. Leader of the raid James Andrews was caught and hanged as a Union spy. He alone was judged ineligible for the medal of honor, as he was a civilian. Few soldiers on the Civil War battlefield had a quicker route to death’s door, than the color bearer. National and regimental flags were all-important sources of inspiration and communication.

Few soldiers on the Civil War battlefield had a quicker route to death’s door, than the color bearer. National and regimental flags were all-important sources of inspiration and communication.

Father

Father

Sint Eustatius, known to locals as “Statia”, is a Caribbean island of 8.1 sq. miles in the northern Leeward Islands. Formerly part of the Netherlands Antilles, the island lies southeast of the Virgin Islands, immediately to the northwest of Saint Kitts.

Sint Eustatius, known to locals as “Statia”, is a Caribbean island of 8.1 sq. miles in the northern Leeward Islands. Formerly part of the Netherlands Antilles, the island lies southeast of the Virgin Islands, immediately to the northwest of Saint Kitts.

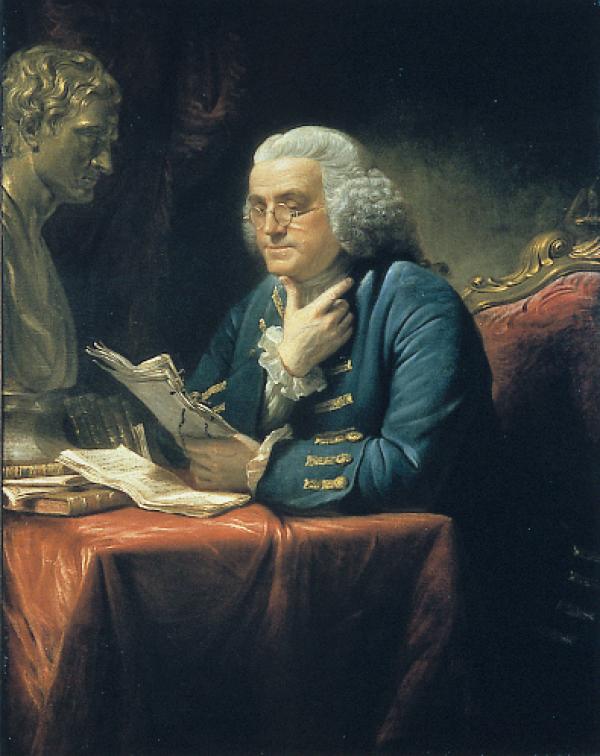

On the 16th of November, 1776, the Brig Andrew Doria sailed into Sint Eustatius’ principle anchorage in Oranje Bay. Flying the Continental Colors of the fledgling United States and commanded by Captain Isaiah Robinson, the Brig was there to obtain munitions and military supplies. Andrew Doria also carried a precious cargo, a copy of the Declaration of Independence.

On the 16th of November, 1776, the Brig Andrew Doria sailed into Sint Eustatius’ principle anchorage in Oranje Bay. Flying the Continental Colors of the fledgling United States and commanded by Captain Isaiah Robinson, the Brig was there to obtain munitions and military supplies. Andrew Doria also carried a precious cargo, a copy of the Declaration of Independence. Tradition dictated the firing of a salute in return, typically two guns fewer than that fired by the incoming vessel. Such an act carried meaning. The firing of a return salute was the overt recognition that a sovereign state had entered the harbor. Such a salute amounted to formal recognition of the independence of the 13 American colonies.

Tradition dictated the firing of a salute in return, typically two guns fewer than that fired by the incoming vessel. Such an act carried meaning. The firing of a return salute was the overt recognition that a sovereign state had entered the harbor. Such a salute amounted to formal recognition of the independence of the 13 American colonies. Rodney pretty much had his way. The census of 1790 shows 8,124 on the Dutch island nation. In 1950, the population stood at 790. It would take 150 years from Rodney’s departure, before tourism even began to restore the economic well-being of the tiny island.

Rodney pretty much had his way. The census of 1790 shows 8,124 on the Dutch island nation. In 1950, the population stood at 790. It would take 150 years from Rodney’s departure, before tourism even began to restore the economic well-being of the tiny island.

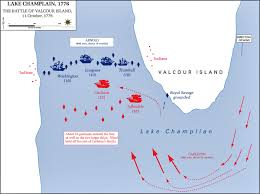

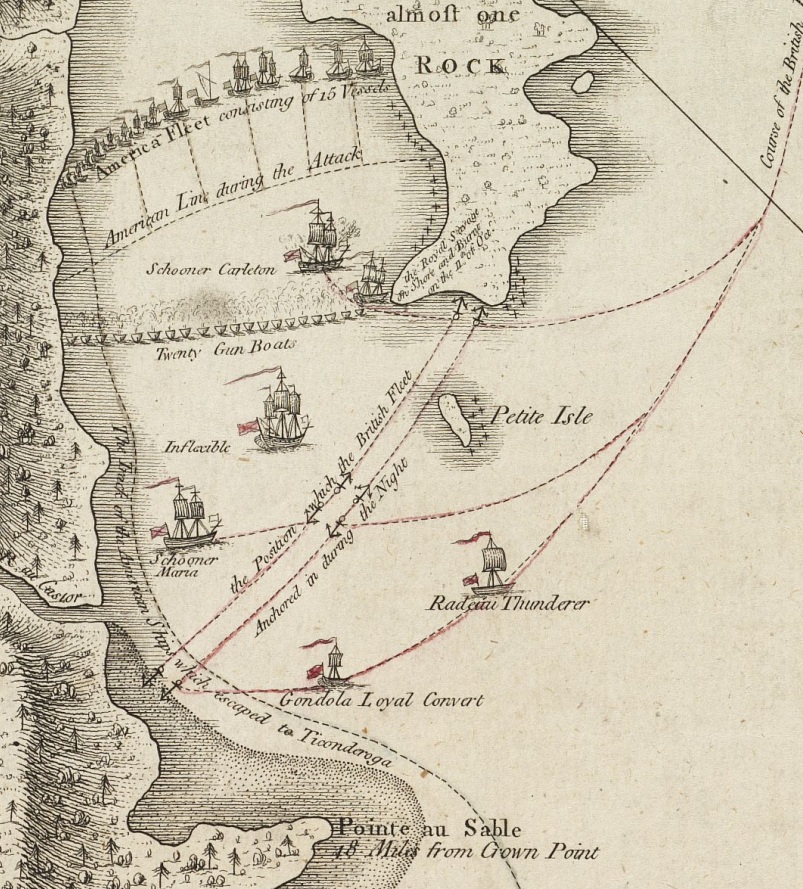

Sailing south on the 11th under favorable winds, some of the British ships had already passed the American position behind Valcour island, before realizing they were there. Some of the British warships were able to turn and give battle, but the largest ones were unable to turn into the wind.

Sailing south on the 11th under favorable winds, some of the British ships had already passed the American position behind Valcour island, before realizing they were there. Some of the British warships were able to turn and give battle, but the largest ones were unable to turn into the wind.

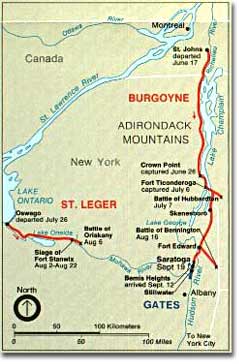

American forces selected a site called Bemis Heights, about 10 miles south of Saratoga, spending a week constructing defensive works with the help of Polish engineer Thaddeus Kosciusko. It was a formidable position: mutually supporting cannon on overlapping ridges, with interlocking fields of fire. Burgoyne knew he had no choice but to stop and give battle at the American position, or be chopped to pieces trying to bypass it.

American forces selected a site called Bemis Heights, about 10 miles south of Saratoga, spending a week constructing defensive works with the help of Polish engineer Thaddeus Kosciusko. It was a formidable position: mutually supporting cannon on overlapping ridges, with interlocking fields of fire. Burgoyne knew he had no choice but to stop and give battle at the American position, or be chopped to pieces trying to bypass it. The second and decisive battle for Saratoga, the Battle of Bemis Heights, occurred on October 7, 1777.

The second and decisive battle for Saratoga, the Battle of Bemis Heights, occurred on October 7, 1777.

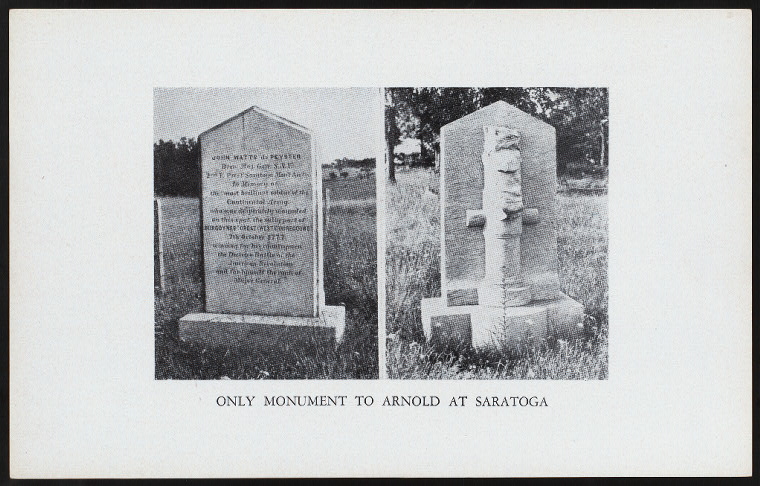

Today, the Saratoga battlefield and the site of Burgoyne’s surrender are preserved as the Saratoga National Historical Park. On the grounds of the park stands an obelisk, containing four niches.

Today, the Saratoga battlefield and the site of Burgoyne’s surrender are preserved as the Saratoga National Historical Park. On the grounds of the park stands an obelisk, containing four niches.

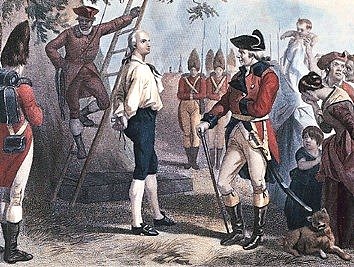

Washington asked for volunteers for a dangerous mission, to go behind enemy lines, as a spy. Up stepped a volunteer. His name was Nathan Hale.

Washington asked for volunteers for a dangerous mission, to go behind enemy lines, as a spy. Up stepped a volunteer. His name was Nathan Hale. Hale took Rogers into his confidence, believing the two to be playing for the same side. Barkhamsted Connecticut shopkeeper Consider Tiffany, a British loyalist and himself a sergeant of the French and Indian War, recorded what happened next, in his journal: “The time being come, Captain Hale repaired to the place agreed on, where he met his pretended friend” (Rogers), “with three or four men of the same stamp, and after being refreshed, began [a]…conversation. But in the height of their conversation, a company of soldiers surrounded the house, and by orders from the commander, seized Captain Hale in an instant. But denying his name, and the business he came upon, he was ordered to New York. But before he was carried far, several persons knew him and called him by name; upon this he was hanged as a spy, some say, without being brought before a court martial.”

Hale took Rogers into his confidence, believing the two to be playing for the same side. Barkhamsted Connecticut shopkeeper Consider Tiffany, a British loyalist and himself a sergeant of the French and Indian War, recorded what happened next, in his journal: “The time being come, Captain Hale repaired to the place agreed on, where he met his pretended friend” (Rogers), “with three or four men of the same stamp, and after being refreshed, began [a]…conversation. But in the height of their conversation, a company of soldiers surrounded the house, and by orders from the commander, seized Captain Hale in an instant. But denying his name, and the business he came upon, he was ordered to New York. But before he was carried far, several persons knew him and called him by name; upon this he was hanged as a spy, some say, without being brought before a court martial.” There is no official account of Nathan Hale’s final words, but we have an eyewitness statement from British Captain John Montresor, who was present at the hanging.

There is no official account of Nathan Hale’s final words, but we have an eyewitness statement from British Captain John Montresor, who was present at the hanging.

You must be logged in to post a comment.