With increasing tensions between the Unites States and the empire of Japan, the “China Marines” of the Fourth Marine Regiment, “The Oldest and the Proudest”, departed Shanghai for the Philippines on November 27-28, 1941. The first elements arrived at Subic Bay on November 30.

A week later and 5,000 miles to the east, the radio crackled to life in the early – morning hours of December 7. “Air raid on Pearl Harbor. This is no drill!”

Military forces of Imperial Japan appeared unstoppable in the early months of WWII, attacking first Thailand, then the British possessions of Malaya, Singapore and Hong Kong, as well as US military bases in Hawaii, Wake Island, Guam and the Philippines.

On January 7, Japanese forces attacked the Bataan peninsula. The Fourth Marines, under Army command, were ordered to help strengthen defenses on the “Gibraltar of the East”, the heavily fortified island of Corregidor.

The prize was nothing less than the finest natural harbor in the Asian Pacific, Manila Bay, the Bataan Peninsula forming the lee shore and Corregidor and nearby Caballo Islands standing at the mouth, dividing the entrance into two channels. Before the Japanese invasion was to succeed, Bataan and Corregidor must be destroyed.

The United States was grossly unprepared to fight a World War in 1942. The latest iteration of “War Plan Orange” (WPO-3) called for delaying tactics in the event of war with Japan, buying time to gather US Naval assets to sail for the Philippines. The problem was, there was no fleet to gather. The flower of American pacific power in the pacific, lay at the bottom of Pearl Harbor. Allied war planners turned their attention to defeating Adolf Hitler.

The United States was grossly unprepared to fight a World War in 1942. The latest iteration of “War Plan Orange” (WPO-3) called for delaying tactics in the event of war with Japan, buying time to gather US Naval assets to sail for the Philippines. The problem was, there was no fleet to gather. The flower of American pacific power in the pacific, lay at the bottom of Pearl Harbor. Allied war planners turned their attention to defeating Adolf Hitler.

General Douglas MacArthur abandoned Corregidor on March 12, departing the “Alamo of the Pacific” with the words, “I shall return”. Some 90,000 American and Filipino troops were left behind without food, supplies or support with which to fight off the onslaught of the Japanese 14th Army, under the command of Lieutenant General Masaharu Homma.

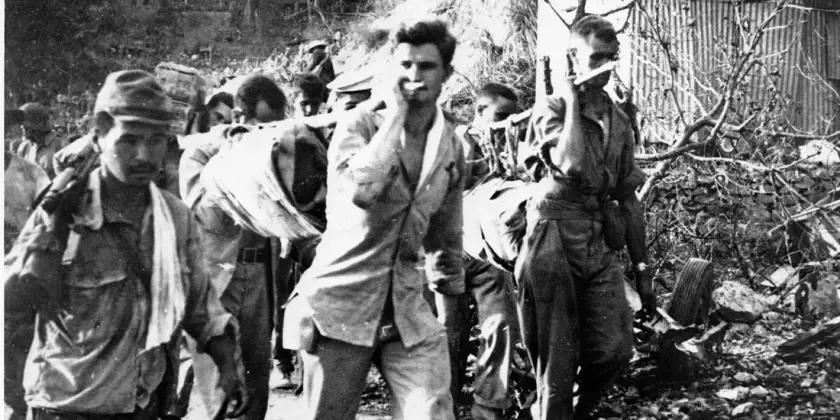

Battered by wounds and starvation, decimated by all manner of tropical disease and parasite, the 75,000 “Battling Bastards of Bataan” fought on until they could fight no more. Some 75,000 American and Filipino fighters were surrendered with the Bataan peninsula on April 9, only to begin a 65-mile, five-day slog into captivity through the unbearable heat and humidity, of the Philippine jungle. The Japanese were sadistic. Guards would beat marchers and bayonet those too weak to walk. Tormented by a thirst few among us can even imagine, men were made to stand for hours under a relentless sun, standing by a stream from which none were permitted to drink. The man who broke ranks and dove for the water was clubbed or bayoneted to death, on the spot. Japanese tanks would swerve out of their way to run over anyone who had fallen and was too slow in getting up. Some were burned alive, others buried alive. Already crippled from tropical disease and starving from the long siege of Luzon, wanton killing and savage abuse took the lives of some 500 – 650 Americans and between 5,000 – 18,000 Filipinos.

The Japanese were sadistic. Guards would beat marchers and bayonet those too weak to walk. Tormented by a thirst few among us can even imagine, men were made to stand for hours under a relentless sun, standing by a stream from which none were permitted to drink. The man who broke ranks and dove for the water was clubbed or bayoneted to death, on the spot. Japanese tanks would swerve out of their way to run over anyone who had fallen and was too slow in getting up. Some were burned alive, others buried alive. Already crippled from tropical disease and starving from the long siege of Luzon, wanton killing and savage abuse took the lives of some 500 – 650 Americans and between 5,000 – 18,000 Filipinos.

For those who survived the “Bataan Death March”, this was only the beginning of their ordeal.

United States Marine Corps 1st Lieutenant Austin Shofner came ashore back in November, with the 4th Marines. Shofner and his fellow leathernecks engaged the Japanese as early as December 12 and received their first taste of aerial bombardment, on December 29. Promoted to Captain and placed in command of Headquarters Company, Shofner received two Silver Stars by April 15 in near-constant defense against aerial attack.

United States Marine Corps 1st Lieutenant Austin Shofner came ashore back in November, with the 4th Marines. Shofner and his fellow leathernecks engaged the Japanese as early as December 12 and received their first taste of aerial bombardment, on December 29. Promoted to Captain and placed in command of Headquarters Company, Shofner received two Silver Stars by April 15 in near-constant defense against aerial attack.

For three months, defenders on Corregidor were required to resist near constant aerial, naval and artillery bombardment. All that on two scant water rations and a meager food allotment of only 30 ounces per day.

I don’t know about you, but I’ve eaten Steaks bigger than 30 ounces.

Beset as they were, seven private maritime vessels attempted to run the Japanese gauntlet, loaded with food and supplies. The MV Princessa commanded by 3rd Lieutenant Zosimo Cruz (USAFFE), was the only ship to arrive in Corregidor.

Japanese artillery bombardment intensified, following the fall of Bataan. Cavalry horses killed in the onslaught were dragged into tunnels and caves, and consumed. Japanese aircraft dropped 1,701 bombs in the tiny island during 614 sorties, armed with some 365-tons of high explosive. On May 4 alone, an estimated 16,000 shells hit the little island.

The final assault beginning May 5 met with savage resistance, but the outcome was never in doubt. General Jonathan Wainwright was in overall command of the defenders on Corregidor. Some 11,000 men comprised of United States Marines, Army and Navy and an assemblage of Filipino fighters. The “Malinta Tunnel” alone contained over a thousand, so sick or wounded as to be helpless. Fewer than half had even received training in ground combat techniques.

All were starved, sick, utterly exhausted. The 4th Marines was shattered, no longer an effective fighting force. With the May 6 landing of Japanese tanks, General Wainwright elected the preservation of life over continued slaughter in the defense of a hopeless position. Maine Colonel Samuel Howard ordered the regimental and national colors burned to prevent their capture, as Wainwright sent a radio message to President Roosevelt:

“There is a limit of human endurance, and that point has long been passed.”

Isolated pockets of marines fought on for four hours until at last, all was still. Two officers were sent forward with a white flag, to carry the General’s message of surrender. It was 1:30pm, May 6, 1941. Nearly 150,000 Allied soldiers were taken captive by the Japanese Empire during World War 2. Clad in unspeakably filthy rags they were fed a mere 600 calories per day of fouled rice, supplemented only by the occasional insect or bird or rodent unlucky enough to fall into desperate hands. Diseases like malaria were all but universal as gross malnutrition led to loss of vision and unrelenting nerve pain. Dysentery, a hideously infectious disease of the large intestine reduced grown men to animated skeletons. Mere scratches resulted in grotesque tropical ulcers up to a foot in length exposing living bone and rotting flesh to swarms of ravenous insects.

Nearly 150,000 Allied soldiers were taken captive by the Japanese Empire during World War 2. Clad in unspeakably filthy rags they were fed a mere 600 calories per day of fouled rice, supplemented only by the occasional insect or bird or rodent unlucky enough to fall into desperate hands. Diseases like malaria were all but universal as gross malnutrition led to loss of vision and unrelenting nerve pain. Dysentery, a hideously infectious disease of the large intestine reduced grown men to animated skeletons. Mere scratches resulted in grotesque tropical ulcers up to a foot in length exposing living bone and rotting flesh to swarms of ravenous insects.

The death rate for western prisoners was 27.1% across 130 Japanese prison encampments. Seven times the death toll for allied prisoners in Nazi Germany, or Fascist Italy. Given such cruel conditions it’s a wonder anyone escaped at all but it did happen. One time.

Given such cruel conditions it’s a wonder anyone escaped at all but it did happen. One time.

Austin Schofner and his group were moved from camp to camp. Bilibid. Cabanatuan. Davao. Throughout early 1943, Schofner and others would steal away from work details to squirrel away small caches of food and tools, in the jungle. Nine fellow Marines and two Filipino soldiers were in on the scheme. On April 4, the 12 men quietly slipped away from work parties.

Over the long hours of April 5-6, the group crept through the jungle, dodging enemy patrols and managing to avoid detection, arriving on the 7th at a remote Filipino Guerrilla outpost. Guided by wild mountain tribesmen of the Ata Manobo, the Marines rejoined the 110th Division, 10th Military District, at this time conducting guerrilla operations against the Japanese occupiers.

Emaciated, sick and weak, these men had reached the end of an ordeal a year and a half in the making. It would be understandable if they were to seek out the relative safety of a submarine bound to Australia, but no. Those physically able to do so joined the guerrillas in fighting the Japanese.

Austin Shofner and his Marines were evacuated that November, aboard the submarine USS Narwhal. For the first time, Japanese atrocities came to light. The Death March, the torture, mistreatment and summary execution of Allied POWs. The public was outraged, leading to a change in Allied war strategy. No longer would the war in the Pacific take a back seat to the effort to destroy the Nazi war machine.

Now-Colonel Shofner volunteered to return to the Pacific where his experience helped with the rescue of 500 prisoners of the infamous POW camp at Cabanatuan on January 30, 1945.

An American military tribunal conducted after the war held Lieutenant General Homma Masaharu, commander of the Japanese invasion forces in the Philippines, guilty of war crimes. He was executed by firing squad on April 3, 1946.

The Davao Dozen conducted the only successful escape from a Japanese Prison camp in all World War 2. They deserve that we remember their names.

The only successful escape from a Japanese Prisoner of war camp in all World War 2, The “Davao Dozen” include Here are the names of the Americans in the Davao Dozen:

Second Lieutenant Leo Boelens

First Lieutenant Michiel Dobervich

Captain William Edwin Dyess

Second Lieutenant Samuel Grashio

First Lieutenant Jack Hawkins

Lieutenant Commander Melvyn McCoy

Sergeant Paul Marshall

Major Stephen Mellnik

Captain Austin Shofner

Sergeant Robert Spielman

Benigno de la Crus

Victorio Jumarong

You must be logged in to post a comment.