Janusz Korczak was a children’s author and pediatrician, a teacher and lifelong learner. A student of pedagogy, Korczak was particularly interested in the art and science of education, and how children learn.

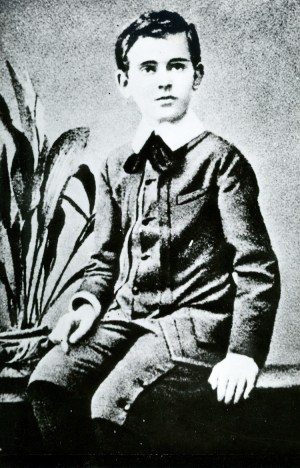

Born Henryk Goldszmit into the Warsaw family of Józef Goldszmit, in 1878 or ’79 (sources vary), Korczak was the pen name by which the physician wrote his children’s books.

Henryk was an exceptional student, of above-average intelligence. His father fell ill when the boy was only eleven or twelve and was admitted into a mental hospital where he died, six years later. As the family’s situation worsened, the boy would tutor other students, to help with household finances.

Goldszmit was a Polish Jew, though not particularly religious, who never believed in forcing religion on children.

He wrote his first book in 1896, a satirical tome on child-rearing, called Węzeł gordyjski (The Gordian Knot). He adopted the pen name Janusz Korczak two years later, writing for the Ignacy Jan Paderewski Literary Contest.

Korczak wrote for several Polish language newspapers while studying medicine at the University of Warsaw, becoming a pediatrician in 1904. Always the writer, Korczak received literary recognition in 1905 with his book Child of the Drawing Room (Dziecko salonu), while serving as medical officer during the Russo-Japanese war.

He went to Berlin to study in 1907-’08 and worked at the Orphan’s Society in 1909, where he met Stefania “Stefa” Wilczyńska, an educator who would become his associate and close collaborator.

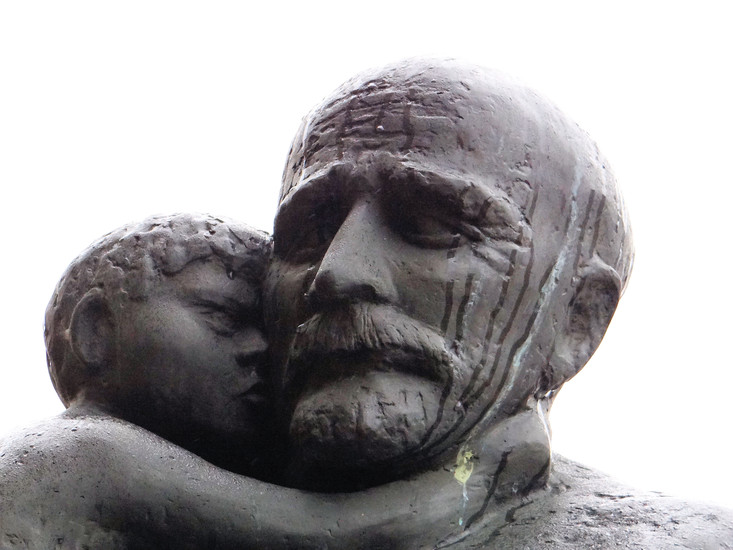

In the years before the Great War, Korczak ran an orphanage of his own design hiring Wilczyńska, as his assistant. There he formed a kind of quasi-Republic for Jewish orphans, complete with its own small parliament, court, and newspaper. The man was a born educator.

In early modern European Royalty, 15th – 18th century, a “whipping boy” was the friend and constant companion to the boy prince or King, whose job it was to get his ass kicked, for the prince’s transgressions. The Lord was not the be struck by a social inferior. It was believed that, to watch his buddy get whipped for his own misdeeds would have the same instructional effect, as the beating itself.

The extent of the custom is open to debate and it may be a myth altogether, but one thing is certain. Poland has been described as the “whipping boy of Europe”, for good reason.

The Polish nation, the sixth largest in all Europe, was sectioned and partitioned for over a century, by Austrian, Prussian, and Russian imperial powers. Korczak volunteered for military service in 1914, serving as military doctor during WW1 and the series of Polish border wars between 1919-’21.

The “Second Polish Republic” emerging from all this in 1922 was roughly two-thirds Polish, the rest a kaleidoscope of ethnic, linguistic and religious minorities. Relations were anything but harmonious between ethnic Russians, Germans, Lipka Tatars and others, and most especially Poland’s Jewish minority, the largest in pre-WW2 Europe.

Janusz Korczak returned to his life’s work in 1921 of providing for the children of this Jewish community, all the while writing no fewer than thirteen children’s books along with another seven on pedagogy, and other subjects.

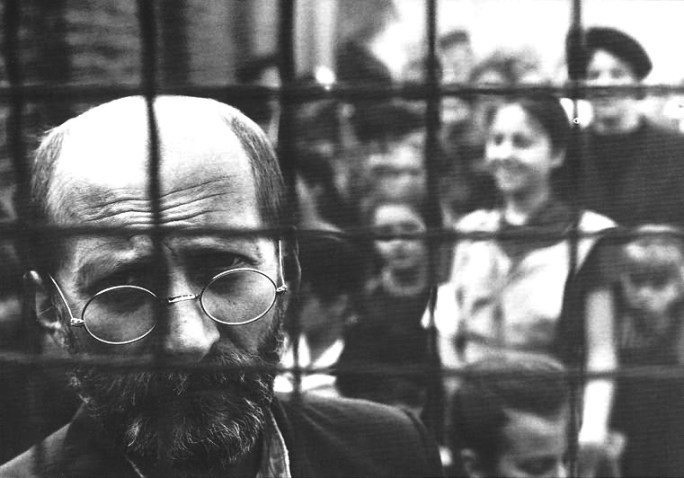

In the inter-war years, Korczak put together a children’s newspaper, the Mały Przegląd (Little Review), as a weekly supplement to the daily Polish-Jewish newspaper, Nasz Przegląd (Our Review).

Korczak had his own radio program promoting the rights of children, to whom he was known as Pan Doktor (“Mr. Doctor”) or Stary Doktor (“Old Doctor”).

The Polish government awarded “Old Doctor” the Polonia Restituta in 1933, a state order bestowed on individuals for outstanding achievements in the fields of education, science and other civic accomplishments.

Yearly visits to Mandatory Palestine, the geopolitical entity partitioned from the Ottoman Empire in 1923 and future Jewish state of Israel, led to anti-Semitic crosscurrents in the Polish press, and gradual estrangement from non-Jewish orphanages.

The second Republic’s brief period of independence came to an end in September 1939, with the Nazi invasion of Poland. Korczak volunteered once again but was refused, due to his age.

Tales of Polish courage in the face of the Wehrmacht are magnificent bordering on reckless, replete with images of horse cavalry riding out to meet German tanks. Poland never had a chance against the Nazi war machine, particularly when the Soviet Union piled on, two weeks later.

As an independent nation-state the Sovereign Republic of Poland was dead, though Polish air crews went on to make the largest contribution to the Battle of Britain, among the United Kingdom’s thirteen non-British defenders and allies. Polish Resistance made significant contributions to the Allied war effort, throughout WW2.

By the following year, Warsaw had become the largest Jewish ghetto in Nazi-occupied Europe. The Jews of Poland were herded into the city, barely existing on meager rations while awaiting the death squads of the SS. Old Doctor and his orphans were forced into the Ghetto, in 1939.

Korczak had around 200 under his care on this day in 1942, when soldiers of the Gross-Aktion (Great Action) Warsaw, came to “resettle” them, to the east.

The extermination camp at Treblinka, was waiting.

Polish-Jewish composer and musician Władysław Szpilman, one of precious few survivors of the Jewish ghetto, describes the scene in his 1946 memoir, The Pianist:

“He told the orphans they were going out into the country, so they ought to be cheerful. At last they would be able to exchange the horrible suffocating city walls for meadows of flowers, streams where they could bathe, woods full of berries and mushrooms. He told them to wear their best clothes, and so they came out into the yard, two by two, nicely dressed and in a happy mood. The little column was led by an SS man…”

Eyewitness Joshua Perle states that: Janusz Korczak was marching, his head bent forward, holding the hand of a child… A few nurses were followed by two hundred children, dressed in clean and meticulously cared for clothes, as they were being carried to the altar.

At the Umschlagplatz, the rail-side assembly area on the way to Treblinka, an SS officer recognized Korczak and called him aside. The children’s author was offered sanctuary on the “Aryan side” but he refused, saying that he would stay with his children. Stary Doktor was offered deportation to the Theresienstadt concentration camp instead. Again, he refused.

The man who declined freedom to die with the orphans in his care was last seen boarding the train to Treblinka on August 5. All 200 were murdered the following day.

“Dr. Janusz Korczak’s children’s home is empty now. A few days ago we all stood at the window and watched the Germans surround the houses. Rows of children, holding each other by their little hands, began to walk out of the doorway. There were tiny tots of two or three years among them, while the oldest ones were perhaps thirteen. Each child carried the little bundle in his hand”.

Mary Berg, The Diary

You must be logged in to post a comment.