From the time of Charlemagne, the social and political structure of Middle Ages European society revolved around a set of reciprocal obligations between a warrior nobility supporting and in turn being supported by, a hierarchy of vassals and fiefs.

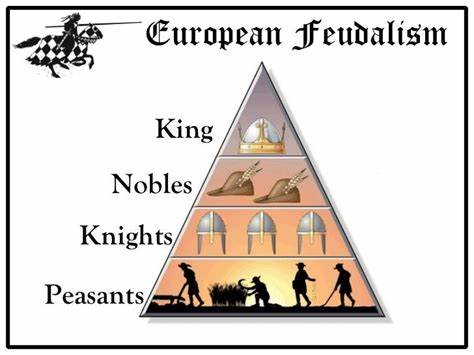

This was Feudalism, a system in which the King granted portions of land called “fiefs” to Lords and Barons in exchange for loyalty, and to Knights (vassals) in exchange for military service.

Knights were a professional warrior class, dependent upon the nobility for lodging, food, armor, weapons, horses and money.

The entire edifice was borne up and supported by peasants, serfs who farmed the land and provided vassal and lord alike with material wealth in the form of food, and other products.

None of this is to be confused with the notion, of chivalry. The 18th century historian and political economist Jean Charles Léonard de Sismondi wrote “We must not confound chivalry with the feudal system. The feudal system may be called the real life of the period of which we are treating, possessing its advantages and inconveniences, its virtues and its vices. Chivalry, on the contrary, is the ideal world, such as it existed in the imaginations of the Romance writers. Its essential character is devotion to woman and to honour”.

Few understood at the time that the whole system was about to come crashing down, near a place called Crécy.

The Battle of Crécy is memorable for several reasons. Crude cannon had appeared in siege operations during the Muslim conquest of Spain, (al Andalus), but this was the first time artillery was used in open battle. Perhaps more important though less evident at the time, was that Crécy spelled the end of feudalism.

The Battle of Crécy was the first major combat of the hundred years’ war, a series of conflicts fought over a 116-year period for control of the French throne. King Edward III invaded the Normandy region of France on July 12, 1346. Estimates vary concerning the size of his army, but not of its composition. This was not an army of mounted knights, though there were a few of those. This was a yeoman army of spearmen and foot archers, ravaging the French countryside as they went and pursued by a far larger army of French knights, and mercenary allies.

A fortunate tidal crossing of the Somme River gave the English a day’s lead, allowing Edward’s forces time to rest and prepare for battle as they stopped near the village of Crécy.

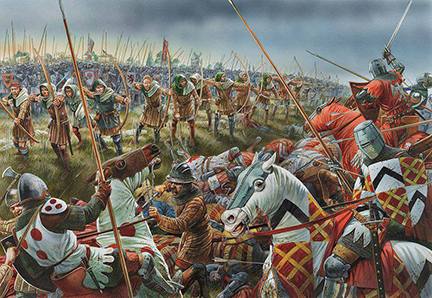

Edward’s forces took a strong defensive position overlooking flat agricultural land, natural obstacles to either side effectively nullifying the French numerical advantage. The French army under King Philip VI was wet and exhausted when they arrived on the 26th but launched themselves nevertheless, directly at the English lines.

Genoese crossbowmen opened the battle on the French side, but wet strings hampered the weapon’s effectiveness. English archers had unstrung longbows during the previous night’s rain, and now showered thousands of arrows down on the heads of the adversary. The French first line broke and ran, only to be accused of cowardice and hacked to pieces by knights to the rear.

French mounted knights now entered the fray, but orderly lines soon dissolved into confusion. The muddy field combined with English obstacles and that constant barrage of arrows unhorsed French knights and confused their lines.

Riderless horses and unmounted knights alike were run down by successive waves of horsemen, each impatient to win his share of the “glory”. Those who made it to the English side faced a tough, disciplined line of spearmen and foot soldiers who held their position. Once unhorsed, heavily armored knights were easy prey to the quick and merciless knives of the English.

In the midst of battle a messenger sought out the English King beseeching aid for the King’s son, the 16-year-old Edward of Woodstock, known as the Black Prince. Edward responded “Do not send to me so long as my son lives; let the boy win his spurs; let the day be his.”

Philip’s ally, the blind King John of Bohemia, heard that the battle was going badly for the French. He ordered his companions to tie his horse’s bridle to theirs, and lead him into the fight. It was the last time he was seen alive.

The Black Prince did indeed earn his spurs that day and, according to legend retrieved the helmet from the dead king and adopted as his own the triple ostrich plume with the words “Ich Dien”. I serve. To this day that heraldic badge symbolizes the the Prince of Wales and heir apparent, to the British throne.

When it was over, the mythical age of chivalry lay dead in the mud and the blood of Crécy, alongside the feudal system. 2,200 Heraldic coats were taken as trophies. The English side suffered 1/10th the number of casualties, as the French.

In the words of A Short History of the English People, by John Richard Green, “The churl had struck down the noble; the bondsman proved more than a match in sheer hard fighting, for the knight”. After Crécy, the world’s land battles would be fought not by armored knights fighting toe-to-toe with battle-axe and lance but by common foot soldiers with bow, spear and gun.

You must be logged in to post a comment.