In the early days of WWII, the British Royal Navy based the main part of the Grand fleet at Scapa Flow, in the Orkney Islands north of Scotland. Protected as it was by blocking ships and underwater cables, the anchorage considered impregnable to submarine attack.

The harbor at Scapa flow had been home to the British deep water fleet since 1904, a time when the place truly was, all but impregnable. By 1939, anti-aircraft weaponry was all but obsolete, old block ships were disintegrating, and anti-submarine nets were inadequate to the needs of the new war.

The harbor at Scapa flow had been home to the British deep water fleet since 1904, a time when the place truly was, all but impregnable. By 1939, anti-aircraft weaponry was all but obsolete, old block ships were disintegrating, and anti-submarine nets were inadequate to the needs of the new war.

The men of the German Unterseeboot U-47 commanded by officer Günther Prien, were not impressed. U-47 entered the Royal Navy base in the evening hours of the October 13, 1939. By 12:55am on the the 14th, they were within 3,500 yards of the unmistakable silhouette of the WWI era Revenge Class Battleship, HMS Royal Oak.

Believing he had a certain kill, Prien aimed two of his four torpedoes at the Battleship, and the other two at the 6,900 ton Pegasus, which he’d mistaken in the dark for the much larger HMS Repulse. Tubes one, two and three fired successfully, torpedoes away, but #4 jammed. Only one found its mark, blowing a hole in the starboard bow of the Royal Oak, near the anchor chains.

On the battleship, Captain William Benn was told the most likely cause was an internal explosion, either that or a high flying German aircraft had dropped a bomb. Damage control teams were assembled to assess the damage, while aboard U-47, Prien thought his one hit had been against Repulse (Pegasus). He was prepared to run, but saw no threat from oncoming surface vessels. Coming about and firing the stern torpedo, the crew worked to free the jammed #4 torpedo tube, while reloading bow tubes 1-3. That one missed as well, and the Germans cursed their luck.

The electric torpedoes of the era were highly unreliable, and this wasn’t shaping up to be their night.

The electric torpedoes of the era were highly unreliable, and this wasn’t shaping up to be their night.

Finally, tubes one and two were reloaded, and the jammed tube #4 was serviced and ready to go. U-47 crept closer and, at 1:25am, fired all three torpedoes at the Royal Oak. All three found their target within ten seconds of one other, blasting three holes amidships on the starboard side. The explosions set off a series of fires and ignited a cordite magazine and exploding with a fiery orange blast that went right through the decks.\

Royal Oak rolled over and sank in thirteen minutes. 833 sailors and officers were lost from ship’s company of 1,234, including Rear Admiral Henry Evelyn Blagrove, commander of the 2nd Battle Squadron.

The Royal Navy considered the anchorage so secure that, even now, searchlights and anti-aircraft fire raked the sky, searching for the air attack that wasn’t there. Captain Benn was almost alone in believing that his ship was attacked by torpedo. The cause of the sinking was still being argued over the next day, when divers went down and found a German torpedo propeller. Only then was it understood that the Kriegsmarine had taken the war, into British home waters.

The successful attack at Scapa Flow was a crushing defeat for the British, and payback for the Germans. The entire German High Seas Fleet had been interned there at the end of WWI. Admiral Ludwig von Reuter wasn’t about to let his fleet fall into allied hands, and ordered the lot of them, scuttled. British guard ships succeeded in beaching a few at the time, but 52 of 74 vessels had sunk to the bottom.

Many of those wrecks were salvaged in the interwar years, and towed away for scrap. Those which remain are popular sites for recreational divers, but not Royal Oak. As a designated war grave, Royal Oak is protected by the Military Remains Act of 1986. Unauthorized divers are strictly, prohibited.

The wreck of the Royal Oak lies nearly upside down in 100′ of water, her hull just 16-feet beneath the surface. Each year, divers place the red St. George’s Cross with the Union Flag of the White Ensign at her stern, a solemn tribute to the honored dead of World War 2, and to the first Royal Navy battleship lost in the most destructive war in history.

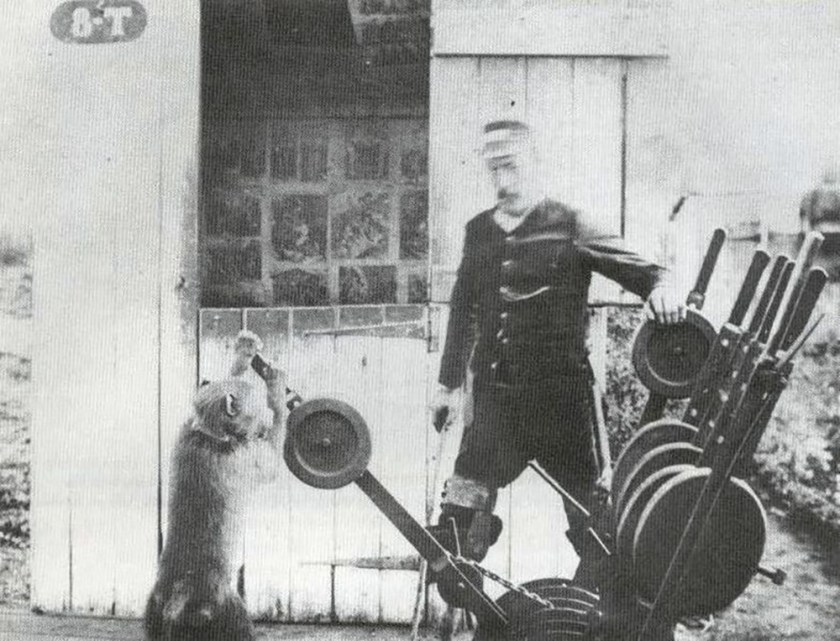

One day at an open-air market, the peg-legged signalman saw something that changed all that. It was a monkey, a Chacma baboon.

One day at an open-air market, the peg-legged signalman saw something that changed all that. It was a monkey, a Chacma baboon.

Juan Garrido moved from the west coast of Africa to Lisbon, Portugal, possibly as a slave, or perhaps the son of an African King, sent for a Christian education. Be that as it may, Garrido came to the new world a free man in 1513, with Juan Ponce de León. A black Conquistador who spent thirty years with the conquest, “pacifying” (fighting) indigenous peoples and searching for gold, and the mythical fountain of youth.

Juan Garrido moved from the west coast of Africa to Lisbon, Portugal, possibly as a slave, or perhaps the son of an African King, sent for a Christian education. Be that as it may, Garrido came to the new world a free man in 1513, with Juan Ponce de León. A black Conquistador who spent thirty years with the conquest, “pacifying” (fighting) indigenous peoples and searching for gold, and the mythical fountain of youth. The Spanish government in Florida began to offer asylum to slaves from British colonies as early as 1687, when eight men, two women and a three year old nursing child arrived there, seeking refuge. It probably wasn’t as altruistic as it sounds, given the history. The primary interest seems to have been disrupting the English agricultural economy, to the north.

The Spanish government in Florida began to offer asylum to slaves from British colonies as early as 1687, when eight men, two women and a three year old nursing child arrived there, seeking refuge. It probably wasn’t as altruistic as it sounds, given the history. The primary interest seems to have been disrupting the English agricultural economy, to the north.

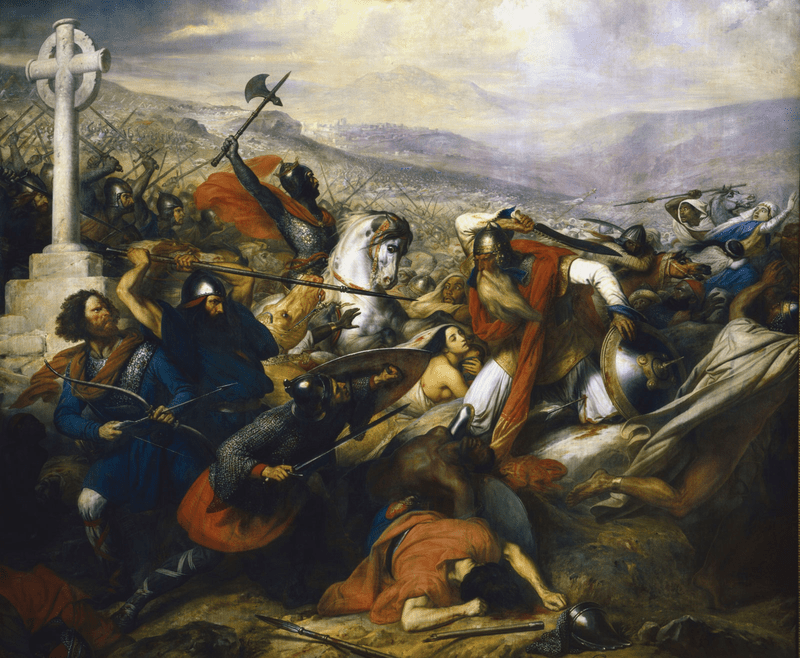

Charles consolidated his power in a series of wars between 718 and 732, subjugating Bavarians Allemanii, and pagan Saxons, and combining the formerly separate Kingdoms of Nuestria in the northwest of modern day France with that of Austrasia in the east.

Charles consolidated his power in a series of wars between 718 and 732, subjugating Bavarians Allemanii, and pagan Saxons, and combining the formerly separate Kingdoms of Nuestria in the northwest of modern day France with that of Austrasia in the east.

It’s not well known that the American Revolution was fought in the midst of a smallpox pandemic. General George Washington was an early proponent of vaccination, an untold benefit to the American war effort, but a fever broke out among shipbuilders which nearly brought their work to a halt.

It’s not well known that the American Revolution was fought in the midst of a smallpox pandemic. General George Washington was an early proponent of vaccination, an untold benefit to the American war effort, but a fever broke out among shipbuilders which nearly brought their work to a halt.

200 were able to escape to shore, the last of whom was Benedict Arnold himself, who personally torched his own flagship, the Congress, before leaving it behind, flag still flying.

200 were able to escape to shore, the last of whom was Benedict Arnold himself, who personally torched his own flagship, the Congress, before leaving it behind, flag still flying.

Umm. What?!

Umm. What?!

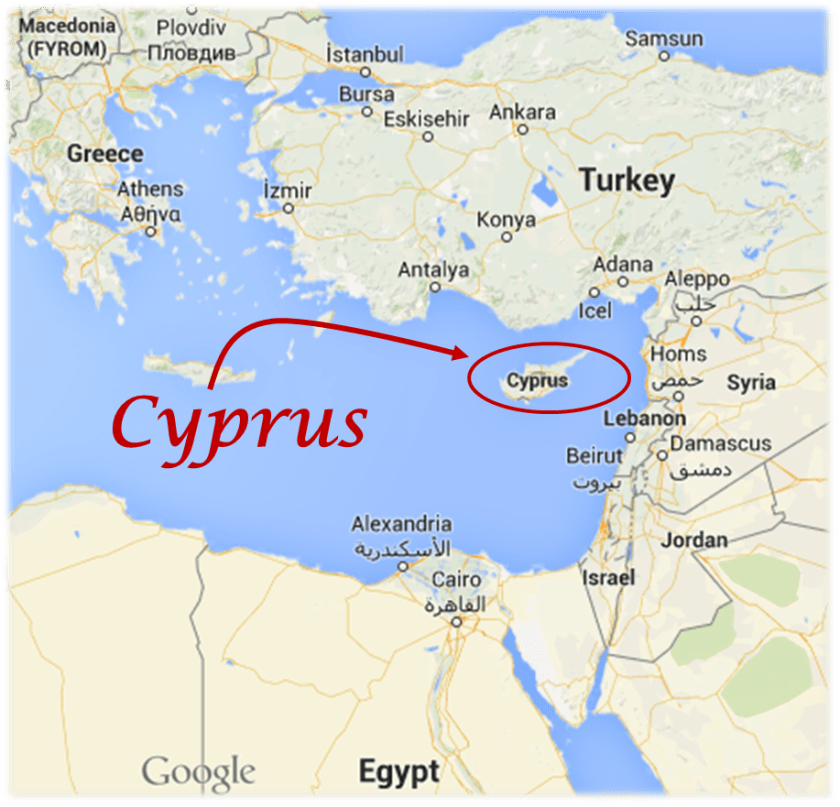

Selim’s son and successor would become the tenth and longest-ruling Ottoman Sultan in 1520, until his death in 1566. He was “Süleiman the Magnificent”, a man who, at his height, ruled over some fifteen to twenty million, at a time when the entire world contained fewer than 500 million

Selim’s son and successor would become the tenth and longest-ruling Ottoman Sultan in 1520, until his death in 1566. He was “Süleiman the Magnificent”, a man who, at his height, ruled over some fifteen to twenty million, at a time when the entire world contained fewer than 500 million

Yet, the suffering inflicted by the curse of the Black Sox and that of the Bambino, pales in comparison with the 108-year drought afflicting the Chicago Cubs since back-to-back championships in 1907/1908. And they say it’s the fault of a Billy goat.

Yet, the suffering inflicted by the curse of the Black Sox and that of the Bambino, pales in comparison with the 108-year drought afflicting the Chicago Cubs since back-to-back championships in 1907/1908. And they say it’s the fault of a Billy goat.

Billy Sianis himself is gone now, but they brought his nephew Sam onto the field with a goat in 1984, to help break the curse. They did it again in 1989, 1994 and 1998, and always the same result.

Billy Sianis himself is gone now, but they brought his nephew Sam onto the field with a goat in 1984, to help break the curse. They did it again in 1989, 1994 and 1998, and always the same result. For fourteen years, Chicago mothers frightened wayward children into behaving, with the name of Steve Bartman.

For fourteen years, Chicago mothers frightened wayward children into behaving, with the name of Steve Bartman.

The cookies pictured above were baked in 2016, and that might’ve finally done it. That’s right. The Mother of all Droughts came to a halt in extra innings of game seven, following a 17-minute rain delay. At long last, Steve Bartman could emerge from Chicago’s most unforgiving doghouse, his way now lit by his own World Series ring. The ghost of Billy Sianis’ goat, may finally rest in peace.

The cookies pictured above were baked in 2016, and that might’ve finally done it. That’s right. The Mother of all Droughts came to a halt in extra innings of game seven, following a 17-minute rain delay. At long last, Steve Bartman could emerge from Chicago’s most unforgiving doghouse, his way now lit by his own World Series ring. The ghost of Billy Sianis’ goat, may finally rest in peace.

Elsbeth had to flee with her infant son in the harsh winter of 1945, as the oncoming Soviet Red Army destroyed all in its path. The two would escape the Iron Curtain once again in 1948, this time in a dangerous nighttime dash which the then-four year old remembers, to this day.

Elsbeth had to flee with her infant son in the harsh winter of 1945, as the oncoming Soviet Red Army destroyed all in its path. The two would escape the Iron Curtain once again in 1948, this time in a dangerous nighttime dash which the then-four year old remembers, to this day. By this time, Joachim Krauledat had taken to calling himself John Kay. The band added a couple new members in 1967, changing their name to a character from a Herman Hesse novel. “Steppenwolf”.

By this time, Joachim Krauledat had taken to calling himself John Kay. The band added a couple new members in 1967, changing their name to a character from a Herman Hesse novel. “Steppenwolf”. Steppenwolf gave us 22 albums, and we all know them in one way or another. Yet, the lead singer’s escape from the horrors of the Iron Curtain, is all but unknown. That, as Paul Harvey used to say, is the Rest of the Story.

Steppenwolf gave us 22 albums, and we all know them in one way or another. Yet, the lead singer’s escape from the horrors of the Iron Curtain, is all but unknown. That, as Paul Harvey used to say, is the Rest of the Story.

You must be logged in to post a comment.