Private James Donovan was AWOL. He had overstayed his leave in the French town of Montremere, and the ‘Great War’, awaited.

When the MPs found him, Donovan knew he had to think fast. He reached down and grabbed a stray dog, explaining to the two policemen that he was part of a search party, sent out to find the Division Mascot.

It was a small dog, possibly a Cairn Terrier mix, about twenty-five pounds. He looked like a pile of rags, and that’s what they called him. The dog had gotten Donovan out of a jam, now he would become the division mascot, for real. Rags was now part of the US 1st Infantry Division, the Big Red One.

Instead of “shaking hands”, Donovan taught the dog a sort of doggie “salute”. Rags would appear at the flag pole for Retreat for years after the war, lifting his paw and holding it by his head. Every time the flag was lowered and the bugle played, there was that small terrier, saluting with the assembled troops.

The dog learned to imitate the men around him, who would drop to the ground and hug it tightly during artillery barrages. He would hug the ground with his paws spread out, soon the doughboys noticed him doing it before any of them knew they were under fire. Rags’ acute and sensitive hearing became an early warning system, telling them that shells were incoming, well before anyone heard them.

Rags was disdainful of doggie tricks, he was more interested in Doing something. In the hell of life in the trenches, barbed wire was often all that stood between safety and enemy attack. Wire emplacements were frequent targets for bombardment, and a break in the wire represented a potentially lethal weak point in the lines. Somehow, Rags could find these breaks in the wire, and often led men into the darkness, to effect repairs.

Thousands of dogs, horses and pigeons were “enlisted” in the first world war, with a number of tasks. The French trained specialized “chiens sanitaire” to seek out the dead and wounded, and bring back small bits of uniform so that aid could be delivered, or the body recovered. Somehow, Rags figured this job out, for himself. Once he found a dead runner, and recovered the note the man had died, trying to deliver. Not only was his body found, but that note enabled the rescue of an officer, cut off and surrounded by Germans.

Donovan’s job was hazardous. He was out on the front lines, stringing communications wire between advancing infantry and supporting field artillery. Runners were used to carry messages until the wire was laid, but these were frequently wounded, killed or they couldn’t get through the shell holes and barbed wire.

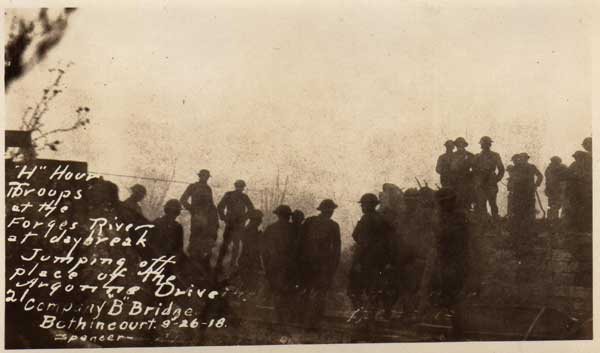

Donovan trained Rags to carry messages attached to his collar. On this day in 1918, British and French forces were engaged in heavy fighting from St. Quentin to Cambrai. French and Americans in the Champagne region advanced as far as the Arnes, as the American attack ground on, west of the River Meuse. Around this time, Rags was given a message from the 26th Infantry Regiment for the 7th Field Artillery. The small dog completing his mission, resulting in an artillery barrage and leading to the capture of the Very-Epinonville Road.

An important objective had been taken, with minimal loss of life to the American side.

The terrier’s greatest trial came five days later, during the Meuse-Argonne Campaign. The small dog ran through falling bombs and poison gas to deliver his message. Gassed and partially blinded, shell splinters damaged his right paw, eye and ear. Rags survived and, so far as I know, got his message where it needed to be.

Rags survived the deadliest battle in American military history, with the loss of an eye. Now-Sergeant James Donovan, wasn’t so lucky. He was severely gassed and the two were brought to the rear. If anyone asked about expending medical care on a dog, they were told that it was “orders from headquarters”.

Rags recovered quickly, but Donovan did not. He was transferred to the hospital ship in Brest, as Rags was forced to look on, from the docks. Animals were thought to carry disease and were strictly forbidden from hospital ships. Those animals who were smuggled on board, were typically chloroformed and thrown overboard.

Nevertheless, Rags was smuggled on board to be with his “Battle Buddy”. How many entered into the conspiracy of silence in his defense, can never be known.

The pair made it back to United States, and to the Fort Sheridan base hospital near Chicago, where medical staff specialized in gas cases. It was here that Rags was given a collar and tag, identifying him as “1st Division Rags”. Donovan died of his injuries, in early 1919. Rags moved into the base fire house becoming “post dog”, until being adopted by Major Raymond W. Hardenbergh, his wife and two daughters, in 1920.

The Big Red One marched down Broadway in 1928, part of the First Division’s 10th anniversary WW1 reunion. The French street dog who had lost an eye in their service, in the lead.

Rags lived out the last of his years in Maryland. A long life it was, too, the dog lived until 1934, remaining with the 1st Infantry Division, for all his 20 years. On March 22, 1934, the 16-paragraph obituary in the New York Times began: “Rags, Dog Veteran of War, Is Dead at 20; Terrier That Lost Eye in Service is Honored.”

Canadian writer Grant Hayter-Menzies has written a book about 1st Division Rags, from which I have drawn some of these details. The book is entitled From Stray Dog to World War I Hero: The Paris Terrier Who Joined the First Division. Eleven-minute audio from a fascinating CBC interview, may be found HERE.

Hat tip to the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, from whose website I have drawn most of these images.

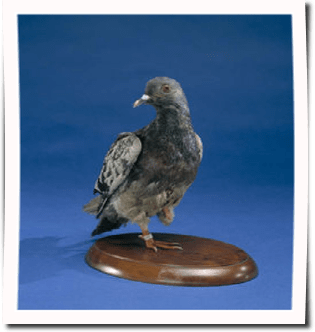

The European allies and Imperial Germany had about 20,000 dogs working a variety of jobs in WWI. Though the United States didn’t have an official “War Dog” program in those days, a Staffordshire Terrier mix called “Sgt. Stubby” was smuggled “over there” with an AEF unit training out of New Haven, Connecticut.

The European allies and Imperial Germany had about 20,000 dogs working a variety of jobs in WWI. Though the United States didn’t have an official “War Dog” program in those days, a Staffordshire Terrier mix called “Sgt. Stubby” was smuggled “over there” with an AEF unit training out of New Haven, Connecticut.

Smoky toured all over the world after the war, appearing in over 42 television programs and licking faces & performing tricks for thousands at veteran’s hospitals. In June 1945, Smoky toured the 120th General Hospital in Manila, visiting with wounded GIs from the Battle of Luzon. She’s been called “the first published post-traumatic stress canine”, and credited with expanding interest in what had hitherto been an obscure breed.

Smoky toured all over the world after the war, appearing in over 42 television programs and licking faces & performing tricks for thousands at veteran’s hospitals. In June 1945, Smoky toured the 120th General Hospital in Manila, visiting with wounded GIs from the Battle of Luzon. She’s been called “the first published post-traumatic stress canine”, and credited with expanding interest in what had hitherto been an obscure breed. A memorial statue was unveiled on December 12 of that year, at the Australian War Memorial at the Queensland Wacol Animal Care Campus in Brisbane.

A memorial statue was unveiled on December 12 of that year, at the Australian War Memorial at the Queensland Wacol Animal Care Campus in Brisbane.

In 1825, Lick left Buenos Aires, for a year-long tour of Europe. This was the time of the Brazilian War for Independence, and Portuguese authorities captured his ship on its return.

In 1825, Lick left Buenos Aires, for a year-long tour of Europe. This was the time of the Brazilian War for Independence, and Portuguese authorities captured his ship on its return. Gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill, shortly after Lick’s arrival. He caught a little of the gold fever himself, but soon learned that he could make more money buying and selling land, rather than digging holes in it.

Gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill, shortly after Lick’s arrival. He caught a little of the gold fever himself, but soon learned that he could make more money buying and selling land, rather than digging holes in it.

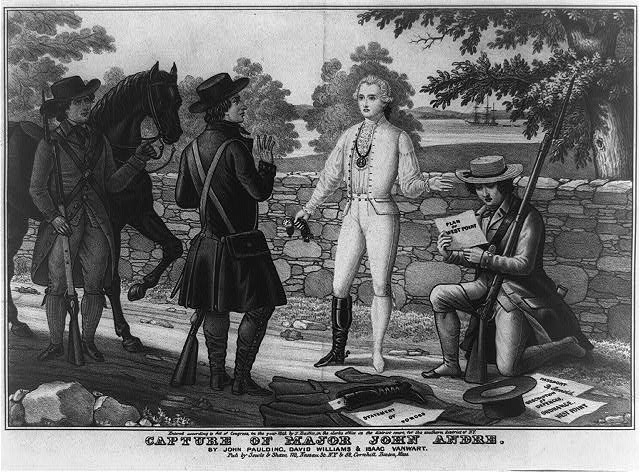

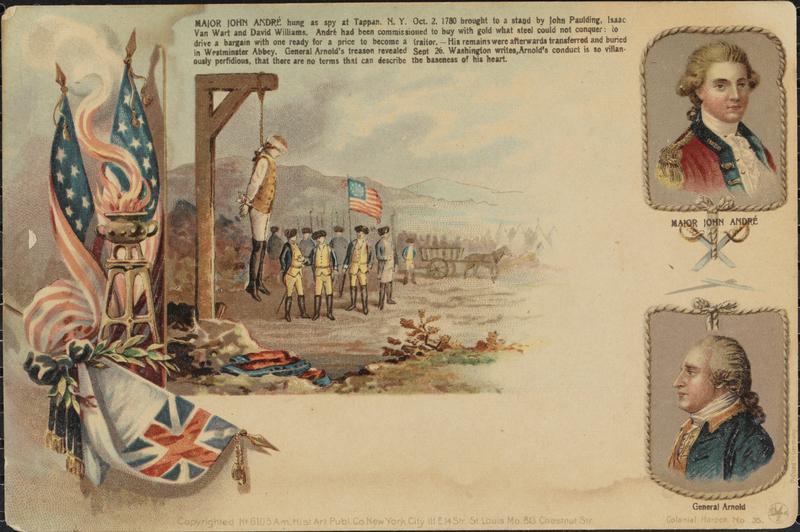

Long afterward, in the early 20th century, the descendants of Major-General Lord Charles Grey returned the painting to the United States, indicating that André had probably looted Franklin’s home under orders from General Grey, himself. A Gentleman always, it would explain the man’s inability to defend his own actions. Today, that oil portrait of Benjamin Franklin hangs in the White House.

Long afterward, in the early 20th century, the descendants of Major-General Lord Charles Grey returned the painting to the United States, indicating that André had probably looted Franklin’s home under orders from General Grey, himself. A Gentleman always, it would explain the man’s inability to defend his own actions. Today, that oil portrait of Benjamin Franklin hangs in the White House.

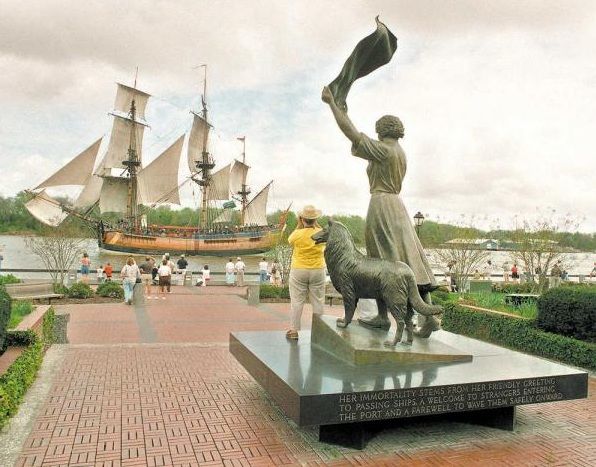

Florence Margaret Martus was born there in 1868, where her father worked as an ordnance sergeant. Martus spent her childhood on the south channel of the Savannah River, moving in with her brother, keeper of the Cockspur Island Lighthouse, when she was 17.

Florence Margaret Martus was born there in 1868, where her father worked as an ordnance sergeant. Martus spent her childhood on the south channel of the Savannah River, moving in with her brother, keeper of the Cockspur Island Lighthouse, when she was 17. So it was that Miss Martus would take out her handkerchief by day or light her lantern by night, and she would greet every vessel that came or went from the Port of Savannah. Every one of them. Some 50,000 vessels, over 44 years.

So it was that Miss Martus would take out her handkerchief by day or light her lantern by night, and she would greet every vessel that came or went from the Port of Savannah. Every one of them. Some 50,000 vessels, over 44 years.

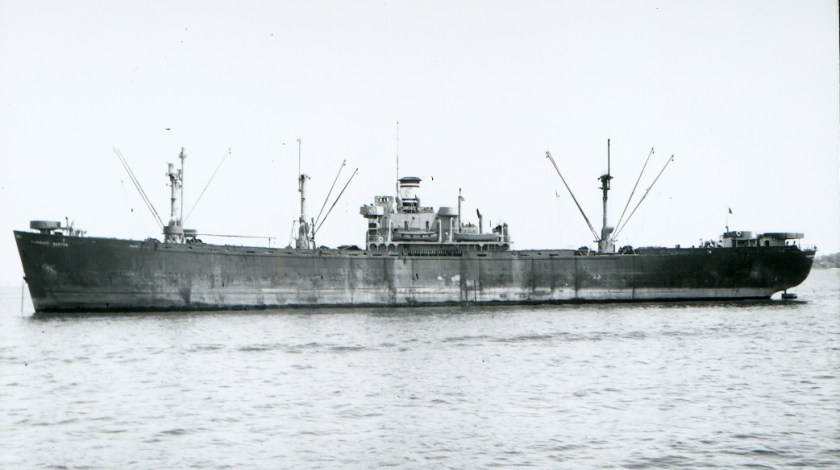

The Southeastern Shipbuilding Corporation of Savannah built 88 Liberty ships during the course of World War II, the light, low-cost cargo ship which came to symbolize the industrial output of the American economy.

The Southeastern Shipbuilding Corporation of Savannah built 88 Liberty ships during the course of World War II, the light, low-cost cargo ship which came to symbolize the industrial output of the American economy.

Bound to a wheelchair after thirteen years and barely able to stand without aid of a walker, Normand Léveillé came back to the Garden twenty-three years ago tonight, to skate there one last time.

Bound to a wheelchair after thirteen years and barely able to stand without aid of a walker, Normand Léveillé came back to the Garden twenty-three years ago tonight, to skate there one last time.

Even at the Constitutional Convention, delegates expressed concerns about the larger, more populous states holding sway, at the expense of the smaller states. The “Connecticut Compromise” solved the problem, creating a bicameral legislature with proportional representation in the lower house (House of Representatives) and equal representation of the states themselves in the upper house (Senate).

Even at the Constitutional Convention, delegates expressed concerns about the larger, more populous states holding sway, at the expense of the smaller states. The “Connecticut Compromise” solved the problem, creating a bicameral legislature with proportional representation in the lower house (House of Representatives) and equal representation of the states themselves in the upper house (Senate). A compromise was reached in February, 1788 whereby Massachusetts and other states would ratify the document, with the assurance that such amendments would immediately be put up for consideration.

A compromise was reached in February, 1788 whereby Massachusetts and other states would ratify the document, with the assurance that such amendments would immediately be put up for consideration.

You must be logged in to post a comment.