The Seven Years War, experienced in the American Colonies as the French and Indian War, ended in 1763 with France ceding vast swaths of the territory of “New France” to the British.

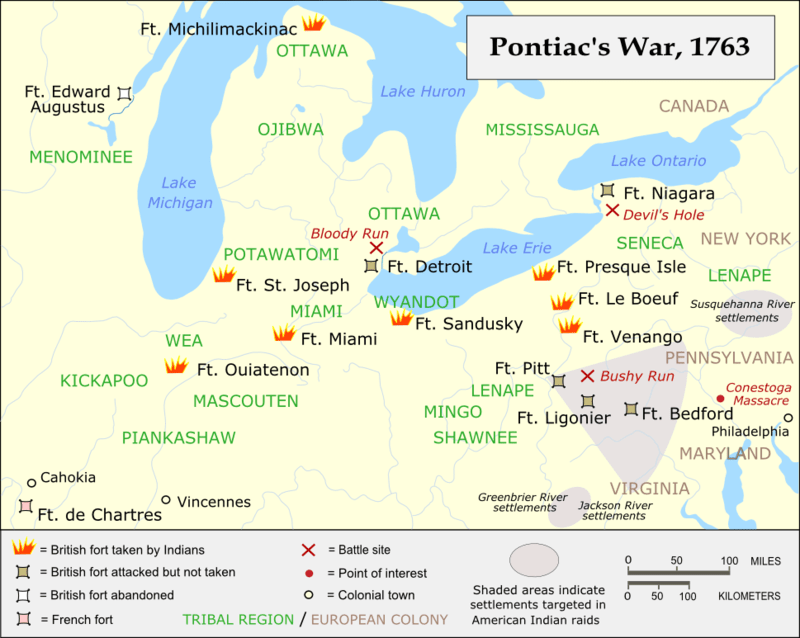

The fourteen Native American tribes involved in Pontiac’s Rebellion lived in a loosely defined region of New France known as the pays d’en haut (“the upper country”), which was claimed by France until the Paris peace treaty of 1763.

Unlike the French, who had cultivated friendships with their Indian allies, the British under Lord Jeffrey Amherst tended to treat indigenous populations with contempt. The first grumblings among the tribes could be heard as early as 1760. The full scale uprising known as “Pontiac’s Rebellion” broke out in May of 1763.

Indian nations of the time divided more along ethnic and linguistic rather than political lines, so there was no monolithic policy among the tribes. Not even within members of the same tribes. Some of the fighting of this time resulted in the murder of women and children. There was torture. There was even an instance of ritual cannibalism. At least one British fort was taken with profuse apologies by the Indians, who explained that it was the other nations making them do it.

The brutality was anything but one sided. The British “Gift” of smallpox infected blankets from Ft. Pitt was hardly the first instance of biological warfare in history, but it may be one of the nastier ones.

The siege of Fort Detroit which began on May 7 was ultimately unsuccessful, but the series of attacks on small forts beginning on May 16 would all result in Indian victories. The fifth and largest of these forts, Fort Michilimackinac in present Mackinaw City, Michigan, was the largest fort taken by surprise. Local Ojibwas staged a game of baaga’adowe on June 2, an early form of lacrosse, with the visiting Sauks in front of the fort.

Native American stickball had many variations, but the object was to hit a stake or other object with a “ball”. The ball was a stone wrapped in leather, handled with one or sometimes two sticks. There could be up to several hundred contestants to a team, and the defenders could employ any means they could think of to get at the ball, including hacking, slashing or any form of physical assault they liked. Lacerations and broken bones were commonplace, and it wasn’t unheard of that stickball players died on the field. The defending team could likewise employ any method they liked to keep the opposing team off of the ball carrier, and they played the game on a field that could range from 500 yards to several miles.

Native American stickball had many variations, but the object was to hit a stake or other object with a “ball”. The ball was a stone wrapped in leather, handled with one or sometimes two sticks. There could be up to several hundred contestants to a team, and the defenders could employ any means they could think of to get at the ball, including hacking, slashing or any form of physical assault they liked. Lacerations and broken bones were commonplace, and it wasn’t unheard of that stickball players died on the field. The defending team could likewise employ any method they liked to keep the opposing team off of the ball carrier, and they played the game on a field that could range from 500 yards to several miles.

The soldiers at Fort Michilimackinac enjoyed the game, as they had on previous occasions. When the ball was hit through the open gate of the fort, both teams rushed in as Indian women handed them weapons previously smuggled into the fort. Fifteen of the 35 man garrison were killed in the ensuing struggle, five others were tortured to death.

Three more forts were taken in a second wave of attacks, when survivors took to the shelter of Fort Pitt, in Western Pennsylvania. The siege which followed was unsuccessful, but a mob of vigilantes from Paxton village – “The Paxton Boys” – slaughtered a number of innocent American Indians, many of them Christians who had nothing to do with the fighting. Many of these peaceful Indians fled east to Philadelphia for protection, when several hundred Paxton residents marched on Philadelphia in January of 1764.

The presence of British troops and Philadelphia militia prevented them from doing any more violence, when Benjamin Franklin, who had helped organize the local militia, met with their leaders and negotiated an end to the crisis. Mr. Franklin may have had the last word on the collectivist nonsense we suffer from today, when he asked “If an Indian injures me, does it follow that I may revenge that injury on all Indians?”

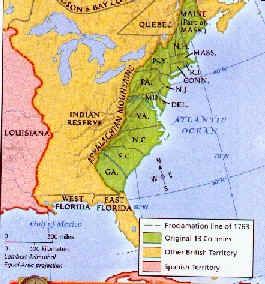

Pontiac’s Rebellion ended in a draw in 1765, but the often genocidal actions on both sides seem to have led both sides to conclude that segregation and not interaction should characterize relations between Indians and whites.

The British Royal Proclamation of October 7, 1763, drew a line between the British colonies and Indian lands, creating a vast Indian Reserve stretching from the Appalachians to the Mississippi River and from Florida to Newfoundland. For the Indian Nations, this was the first time that a multi-tribal effort had been launched against British expansion, the first time such an effort had not ended in defeat.

The British Royal Proclamation of October 7, 1763, drew a line between the British colonies and Indian lands, creating a vast Indian Reserve stretching from the Appalachians to the Mississippi River and from Florida to Newfoundland. For the Indian Nations, this was the first time that a multi-tribal effort had been launched against British expansion, the first time such an effort had not ended in defeat.

The British government had hoped through their proclamation to avoid more conflicts like Pontiac’s Rebellion, but the decree had the effect of alienating colonists against the Crown. For American colonists, many now found themselves on the road to Revolution. The Indian Nations, as they existed at that time, were on the road to ruin.

A really interesting read! Particularly the aftermath

LikeLiked by 1 person