A light rain fell on Heston Aerodrome in London, as thousands thronged the tarmac awaiting the return of British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. Searing memories of the Great War only 20 years in the past, hung over London like some black and malevolent cloud.

Emerging from the door of the aircraft that evening in September, 1938, the Prime minister began to speak. The piece of paper Chamberlain held in his hand annexed that bit of the Czechoslovak Republic known as the “Sudetenland”, to Nazi Germany. Germany’s territorial ambitions to her east, were sated. It was peace in our time.

With the March invasion of Czecho-Slovakia, Hitler demonstrated even to Neville Chamberlain that the so-called Munich agreement, meant nothing. That Poland was next was an open secret. Polish-British mutual aid talks began that April. Two days after Nazi Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Union signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop non-aggression pact, the Polish-British Common Defense Pact was added to the Franco-Polish Military Alliance. Should Poland be invaded by a foreign power, England and France were now committed to intervene. That same month the first fourteen “Unterseeboots” (U-boats) left their bases, fanning out across the North Atlantic.

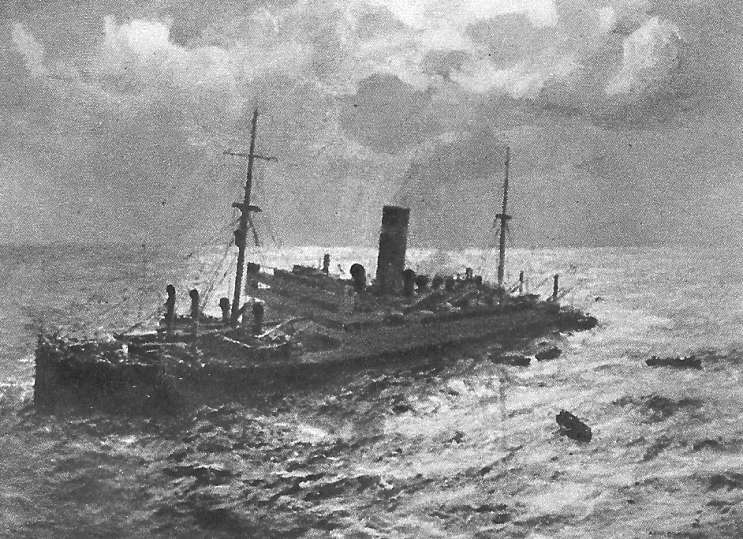

The German invasion of Poland began on September 1, the same day the British passenger liner SS Athenia departed Glasgow for Montreal with 1,418 passengers and crew. Two days later Great Britain and France declared war, on Germany. With the declaration only hours old, Athenia was seating her second round of dinner guests, for the evening.

At 19:40, U-30 Oberleutnant Fritz Julius Lemp fired two torpedos, one striking the liner’s port side engine room. 14 hours later, Athenia sank stern first with the loss of 98 passengers and 19 crew. The Battle of the Atlantic, had begun.

In a repeat of WWI, both England and Germany implemented blockades on one another. And for good reason. At the height of the war England alone required over a million tons a week of imported goods, to survive and to stay in the fight.

The “Battle of the Atlantic” lasted 5 years, 8 months and 5 days ranging from the Irish Sea to the Gulf of Mexico, from the Caribbean to the Arctic Ocean.

New weapons and tactics would shift the balance first in favor of one side, and then to the other. Before it was over 3,500 merchant ships and 175 warships were sunk to the bottom. 500,000 tons of allied shipping was sunk in June 1941, alone.

Nazi Germany lost 783 U-boats.

Submarines operate in 3-dimensional space but their most effective weapon, does not. The torpedo is a surface weapon operating in two-dimensional space: left, right and forward. Firing at a submerged target requires that the torpedo be converted to neutral buoyancy. The complexity of firing calculations are all but insurmountable.

The most unusual underwater action of the war occurred on February 9, 1945 in the form of a combat between two submerged submarines.

The war was going badly for the Axis Powers in 1945, the allies enjoying near-uncontested supremacy over the world’s shipping lanes. Any surface delivery between Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan was sure to be detected and destroyed. The maiden voyage of the 287-foot, 1,799 ton German submarine U-864 departed on “Operation Caesar” on December 5, delivering Messerschmitt jet engine parts, V-2 missile guidance systems and 67 tons of mercury to the Imperial Japanese war production industry.

The mission was a failure, from the start. U-864 ran aground in the Kiel Canal and had to retreat to Bergen, Norway, for repairs. The submarine was able to clear the island of Fedje off the Norway coast undetected on February 6. By this time British MI6 had broken the German Enigma code and were well aware, of Operation Caesar.

The British submarine Venturer, commanded by 25-year-old Lieutenant Jimmy Launders, was dispatched from the Shetland Islands to intercept and destroy U-864.

ASDIC, an early name for sonar, would have been helpful in locating U-864, but at a price. That familiar “ping” would have been heard by both sides, alerting the German commander he was being hunted. Launders opted for hydrophones, a passive listening device which could alert him to external noises. Calculating his adversary’s direction, depth and speed was vastly more complicated without ASDIC but the need for stealth, won out.

U-864 developed an engine noise and commander Ralf-Reimar Wolfram feared it might give him away. The submarine returned to Bergen for repairs. German submarines of the age were equipped with “snorkels”, heavy tubes which broke the surface, enabling diesel engines and crews to breathe while running submerged. Venturer was on batteries when those first sounds were detected.

The British sub had the advantage in stealth but only a short time frame, in which act.

A four dimensional firing solution accounting for time, distance, bearing and target depth was theoretically possible but had rarely been attempted under combat conditions. Unknown factors could only be guessed at.

A fast attack sub Venturer only carried four torpedo tubes, far fewer than her much larger adversary. Launders calculated his firing solution, ordering all four tubes and firing with a 17½ second delay between each pair. With four incoming at different depths, the German sub didn’t have time to react. Wolfram was only just retrieving his snorkel and converting to electric, when the #4 torpedo struck. U-864 imploded and sank, instantly killing all 73 aboard.

So, what about all that mercury?

In our time, authorities recommend consumption limits of certain fish species. Sharp limitations are recommended for pregnant women and nursing mothers.

Fish and shellfish have a natural tendency to concentrate or bioaccumulate mercury in body tissues in the form of methylmercury, a highly toxic organic compound of mercury. Concentrations increase as you move up the underwater food chain. In a process called biomagnification, apex predators such as tuna, swordfish and king mackerel may develop mercury concentrations up to ten times higher than prey species.

The toxic effects of mercury include damage to the brain, kidneys and lungs and long term neurological damage, particularly in children.

Exposures lead to disorders ranging from numbness in the hands and feet, muscle weakness, loss of peripheral vision and damage to hearing and speech.

In extreme cases, symptoms include insanity, paralysis, coma, and death. The range of symptoms was first identified in the city of Minamata, Japan in 1956 and results from high concentrations of methylmercury.

In the case of Minamata, methylmercury originated in industrial wastewater from a chemical factory, bioaccumulated and biomagnified in shellfish and fish in Minamata Bay and the Shiranui Sea. Deaths from Minamata disease continued some 36 years among humans, dogs and pigs. The problem was so severe among cats as to spawn a feline veterinary condition known as “dancing cat fever”.

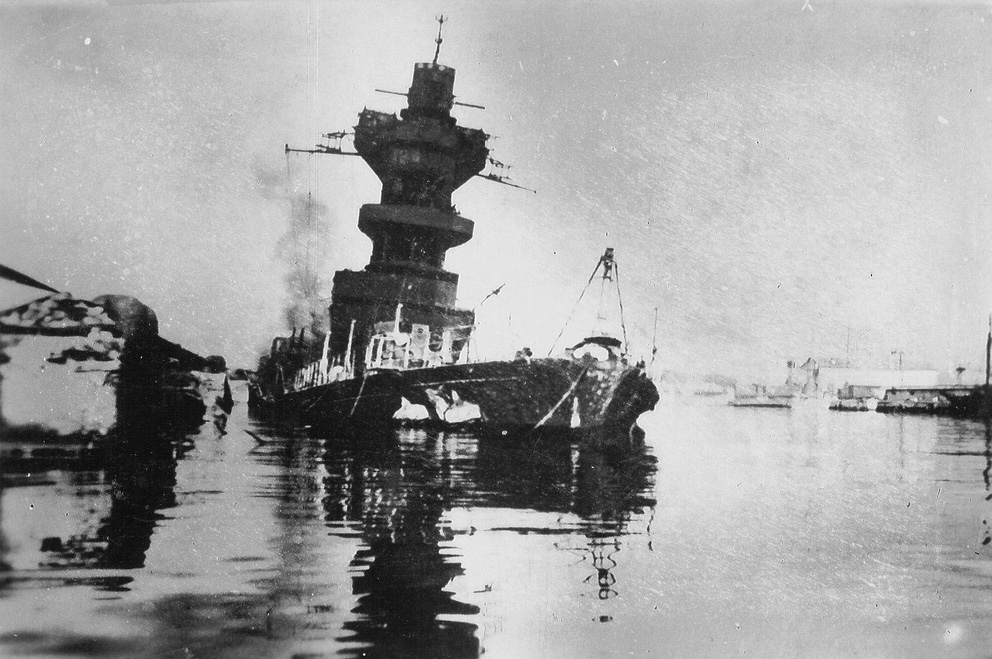

Today, 67 tons of mercury lie under 490-feet of water at the bottom of the north sea, in the broken hull of Adolf Hitler’s last best chance. Rusting containers have already begun to leach toxic mercury into surrounding waters.

The wreck has been called an “underwater Chernobyl”.

Only 4kg are estimated to have leaked so far, about nine pounds, and surrounding waters are already off limits, to fishing. Pregnant and breastfeeding women and young children are advised not to eat fish caught near the wreck.

The wreck was located in 2003. Discussions began almost immediately to retrieve the deadly cargo from what Oslo’s newspaper Dagbladet called, “Hitler’s secret poison bomb.”

Now, 76 years to the day from the last dive of the U-864, the submarine’s hull and mercury containment vessels are believed too fragile to be brought to the surface.

In the fall of 2018, the Norwegian government decided to bury the thing under a great sarcophagus, of concrete and sand. Much the same technique as that used in Chernobyl to sea off contaminated reactors. The work was projected to cost $32 million (US) with completion date, of late 2020. The work was was delayed and once again, the government is now examining the possibility of retrieving the cargo.

In May of 1940 the British Expeditionary Force and what remained of French forces occupied a sliver of land along the English Channel. Field Marshall Gerd von Rundstedt called a halt of the German armored advance on May 24, while Hermann Göring urged Hitler to stop the ground assault, let the Luftwaffe finish the destruction of Allied forces. On the other side of the channel, Admiralty officials combed every boatyard they could find for boats to ferry their people off of the beach.

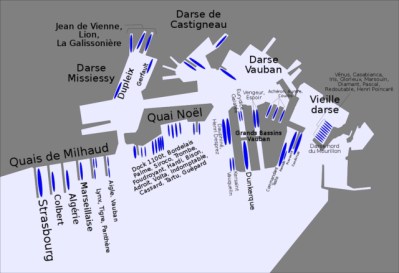

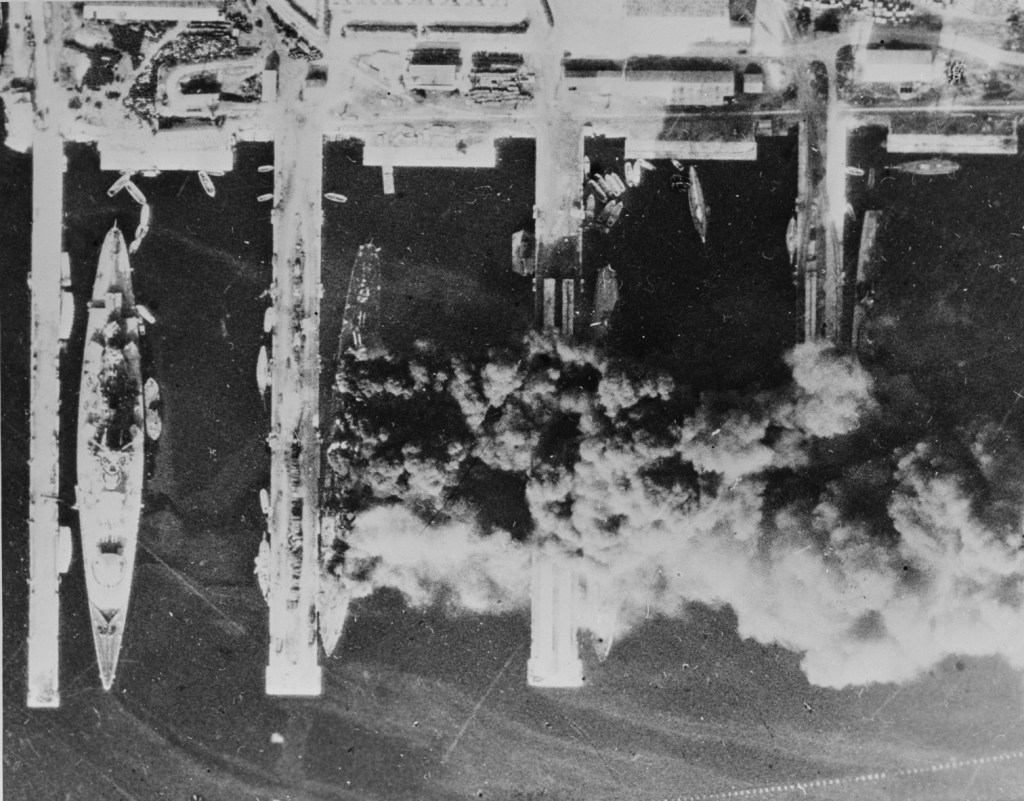

In May of 1940 the British Expeditionary Force and what remained of French forces occupied a sliver of land along the English Channel. Field Marshall Gerd von Rundstedt called a halt of the German armored advance on May 24, while Hermann Göring urged Hitler to stop the ground assault, let the Luftwaffe finish the destruction of Allied forces. On the other side of the channel, Admiralty officials combed every boatyard they could find for boats to ferry their people off of the beach.![dunkirk-evacuation.-1-june-1940-troop-positions.-operation-dynamo.-hmso-1953-map-[2]-272563-p](https://todayinhistory.blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/dunkirk-evacuation.-1-june-1940-troop-positions.-operation-dynamo.-hmso-1953-map-2-272563-p.jpg) The battered remnants of the French 1st Army fought a desperate delaying action against the advancing Germans. They were 40,000 men against seven full divisions, 3 of them armored. They held out until May 31 when, having run out of food and ammunition, the last 35,000 finally surrendered. Meanwhile, a hastily assembled fleet of 933 vessels large and small began to withdraw the broken army from the beaches.

The battered remnants of the French 1st Army fought a desperate delaying action against the advancing Germans. They were 40,000 men against seven full divisions, 3 of them armored. They held out until May 31 when, having run out of food and ammunition, the last 35,000 finally surrendered. Meanwhile, a hastily assembled fleet of 933 vessels large and small began to withdraw the broken army from the beaches. A thousand copies of navigational charts helped organize shipping in and out of Dunkirk, as buoys were laid around Goodwin Sands to prevent stranding. Abandoned vehicles were driven into the water at low tide, weighted down with sand bags and connected by wooden planks, forming makeshift jetties.

A thousand copies of navigational charts helped organize shipping in and out of Dunkirk, as buoys were laid around Goodwin Sands to prevent stranding. Abandoned vehicles were driven into the water at low tide, weighted down with sand bags and connected by wooden planks, forming makeshift jetties. It all came to an end on June 4. Most of the light equipment and virtually all the heavy stuff had to be left behind, just to get what remained of the allied armies out alive. But now, with the United States still the better part of a year away from entering the war, the allies had a fighting force that would live to fight on. Winston Churchill delivered a speech that night to the House of Commons, calling the events in France “a colossal military disaster”. “[T]he whole root and core and brain of the British Army”, he said, had been stranded at Dunkirk and seemed about to perish or be captured. In his “We shall fight on the beaches” speech of June 4, Churchill hailed the rescue as a “miracle of deliverance”.

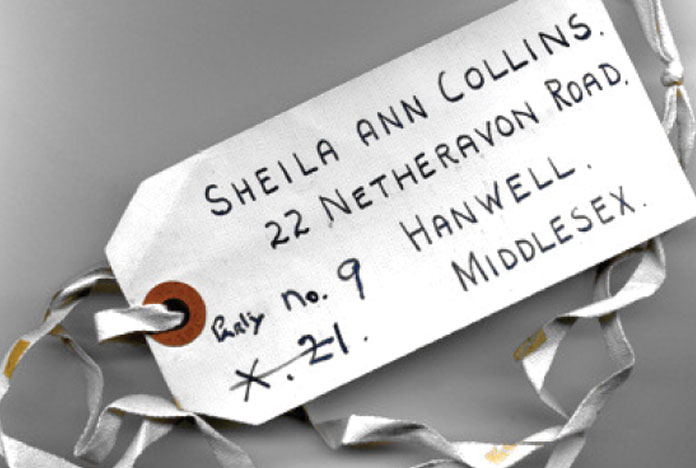

It all came to an end on June 4. Most of the light equipment and virtually all the heavy stuff had to be left behind, just to get what remained of the allied armies out alive. But now, with the United States still the better part of a year away from entering the war, the allies had a fighting force that would live to fight on. Winston Churchill delivered a speech that night to the House of Commons, calling the events in France “a colossal military disaster”. “[T]he whole root and core and brain of the British Army”, he said, had been stranded at Dunkirk and seemed about to perish or be captured. In his “We shall fight on the beaches” speech of June 4, Churchill hailed the rescue as a “miracle of deliverance”. On the home front, thousands of volunteers signed up for a “stay behind” mission in the weeks that followed. With “Operation Sea Lion” all but imminent, the German invasion of Great Britain, their mission was to go underground and to disrupt and destabilize the invaders in any way they could. They were to be part of the Home guard, a guerrilla force reportedly vetted by a senior Police Chief so secret, that he was to be assassinated in case of invasion to prevent membership in the units from being revealed.

On the home front, thousands of volunteers signed up for a “stay behind” mission in the weeks that followed. With “Operation Sea Lion” all but imminent, the German invasion of Great Britain, their mission was to go underground and to disrupt and destabilize the invaders in any way they could. They were to be part of the Home guard, a guerrilla force reportedly vetted by a senior Police Chief so secret, that he was to be assassinated in case of invasion to prevent membership in the units from being revealed.

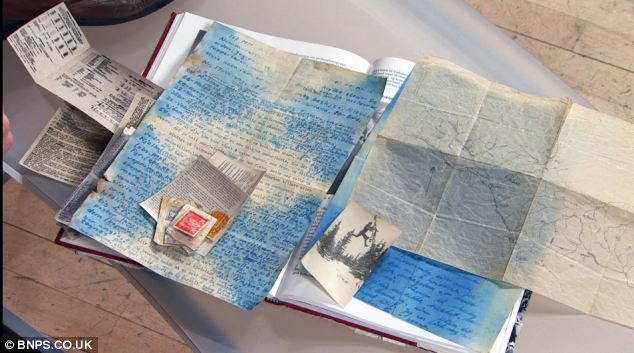

Historians from the Coleshill Auxiliary Research Team (CART) had been trying to do this for years.

Historians from the Coleshill Auxiliary Research Team (CART) had been trying to do this for years.

You must be logged in to post a comment.