In the time of Henry VIII, British military outlays averaged 29.4% as a percentage of central government expenses. That number skyrocketed to 74.6% in the 18th century, and never dropped below 55%.

The Seven Years’ War alone, fought on a global scale from 1756 – ‘63, saw England borrow the unprecedented sum of £58 million, doubling the national debt and straining the British economy.

For the American colonies, the conflict took the form of the French and Indian War. Across the “pond”, the never-ending succession of English wars meant that, not only were colonists left alone to run their own affairs, but individual colonists learned an interdependence of one upon another, resulting in significant economic growth during every decade of the 1700s.

For the American colonies, the conflict took the form of the French and Indian War. Across the “pond”, the never-ending succession of English wars meant that, not only were colonists left alone to run their own affairs, but individual colonists learned an interdependence of one upon another, resulting in significant economic growth during every decade of the 1700s.

Some among the British government saw in the American colonies, the classically “Liberal” notion of the Free Market, as described by intellectuals such as John Locke: “No People ever yet grew rich by Policies,” wrote Sir Dudley North. “But it is Peace, Industry, and Freedom that brings Trade and Wealth“. These, were in the minority. The prevailing attitude at the time, saw the colonies as the beneficiary of much of British government expense. These wanted some help, picking up the tab.

Several measures were taken to collect revenues during the 1760s. Colonists bristled at what was seen as heavy handed taxation policies. The Sugar Act, the Currency Act: in one 12-month period alone, Parliament passed the Stamp Act, Quartering Act, and the Declaratory Act, while deputizing Royal Navy Sea Officers to enforce customs laws in colonial ports.

The merchants and traders of Boston specifically cited “the late war” and the expenses related to it, concluding the Boston Non-Importation Agreement of August 1, 1768. The agreement prohibited the importation of a long list of goods, ending with the statement ”That we will not, from and after the 1st of January 1769, import into this province any tea, paper, glass, or painters colours, until the act imposing duties on those articles shall be repealed”.

The ‘Boston Massacre’ of 1770 was a direct result of the tensions between colonists and

the “Regulars” sent to enforce the will of the Crown. Two years later, Sons of Liberty looted and burned the HMS Gaspee in Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island.

The Tea Act, passed by Parliament on May 10, 1773, was less a revenue measure than it was an effort to prop up the British East India Company, by that time burdened with debt and holding some eighteen million pounds of unsold tea. The measure actually reduced the price of tea, but Colonists saw it as an effort to buy popular support for taxes already in force, and refused the cargo. In Philadelphia and New York, tea ships were turned away and sent back to Britain while in Charleston, the cargo was left to rot on the docks.

British law required a tea ship to offload and pay customs duty within 20 days, or the cargo was forfeit. The Dartmouth arrived in Boston at the end of November with a cargo of tea, followed by the tea ships Eleanor and Beaver. Samuel Adams called for a meeting at Faneuil Hall on the 29th, which then moved to Old South Meeting House to accommodate the crowd. 25 men were assigned to watch Dartmouth, making sure she didn’t unload.

7,000 gathered at Old South Meeting House on December 16th, 1773, the last day of deadline, for Dartmouth’s cargo. Royal Governor Hutchinson held his ground, refusing the vessel permission to leave. Adams announced that “This meeting can do nothing further to save the country.”

7,000 gathered at Old South Meeting House on December 16th, 1773, the last day of deadline, for Dartmouth’s cargo. Royal Governor Hutchinson held his ground, refusing the vessel permission to leave. Adams announced that “This meeting can do nothing further to save the country.”

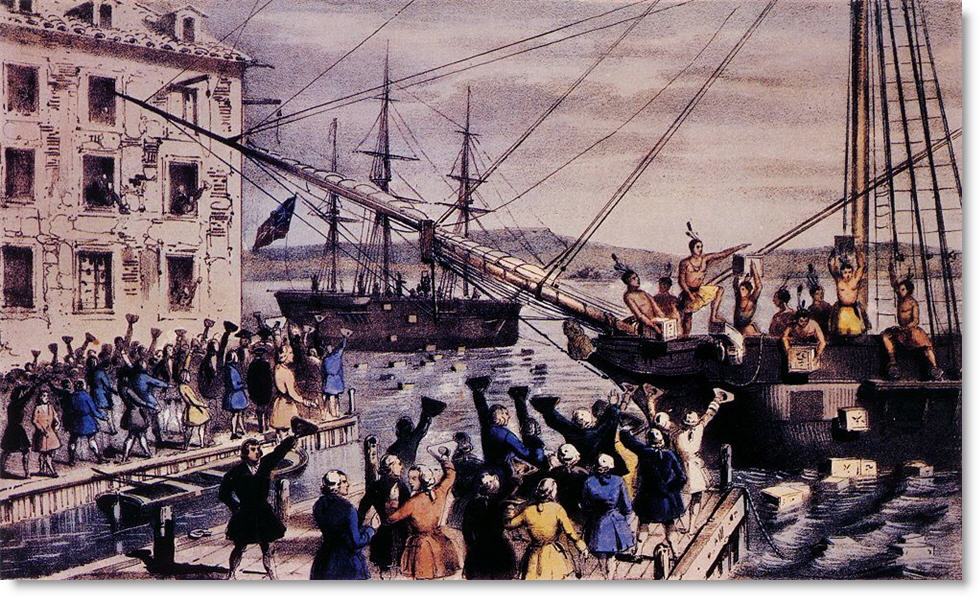

That night, anywhere between 30 and 130 Sons of Liberty, many dressed as Mohawk Indians, boarded the three ships in Boston Harbor. There they threw 342 chests of tea, 90,000 pounds in all, into Boston Harbor. £9,000 worth of tea was destroyed, worth about $1.5 million in today’s dollars.

In the following months, other protesters staged their own “Tea Parties”, destroying imported British tea in New York, Philadelphia, Charleston, and Greenwich, NJ. There was even a second Boston Tea Party on March 7, 1774, when 60 Sons of Liberty, again dressed as Mohawks, boarded the “Fortune”. This time they dumped a ton and one-half of the stuff, into the harbor. That October in Annapolis Maryland, the Peggy Stewart was burned to the water line.

For decades to come, the December 16 incident in Boston Harbor was blithely referred to as “the destruction of the tea.” The earliest newspaper reference to “tea party” wouldn’t come down to us, until 1826.

John Crane of Braintree is one of the few original tea partiers ever identified, and the only man injured in the event. An original member of the Massachusetts Society of the Cincinnati and early member of the Sons of Liberty, Crane was struck on the head by a tea crate and thought to be dead. His body was carried away and hidden under a pile of shavings at a Boston cabinet maker’s shop. It must have been a sight when John Crane “rose from the dead”, the following morning.

Great Britain responded with the “Intolerable Acts” of 1774, including the occupation of  Boston by British troops. Minutemen clashed with “Lobster backs” a few months later, on April 19, 1775. When it was over, eight Lexington men lay dead or dying, another ten wounded. One British soldier was wounded. No one alive today knows who fired the first shot at Lexington Green. History would remember the events of that day as “The shot heard ’round the world”.

Boston by British troops. Minutemen clashed with “Lobster backs” a few months later, on April 19, 1775. When it was over, eight Lexington men lay dead or dying, another ten wounded. One British soldier was wounded. No one alive today knows who fired the first shot at Lexington Green. History would remember the events of that day as “The shot heard ’round the world”.

NAAFI personnel serving on ships are assigned to duty stations and wear uniforms, while technically remaining civilians.

NAAFI personnel serving on ships are assigned to duty stations and wear uniforms, while technically remaining civilians.

Early versions of the German “Enigma” code were broken as early as 1932, thanks to cryptanalysts of the Polish Cipher Bureau, and French spy Hans Thilo Schmidt.

Early versions of the German “Enigma” code were broken as early as 1932, thanks to cryptanalysts of the Polish Cipher Bureau, and French spy Hans Thilo Schmidt. The beginning of the end of darkness came to an end on October 30, when a ship’s cook climbed up that conning ladder. Code sheets allowed British cryptanalysts to attack the “Triton” key used by the U-boat service. It would not be long, before the U-boats themselves, were under attack.

The beginning of the end of darkness came to an end on October 30, when a ship’s cook climbed up that conning ladder. Code sheets allowed British cryptanalysts to attack the “Triton” key used by the U-boat service. It would not be long, before the U-boats themselves, were under attack.

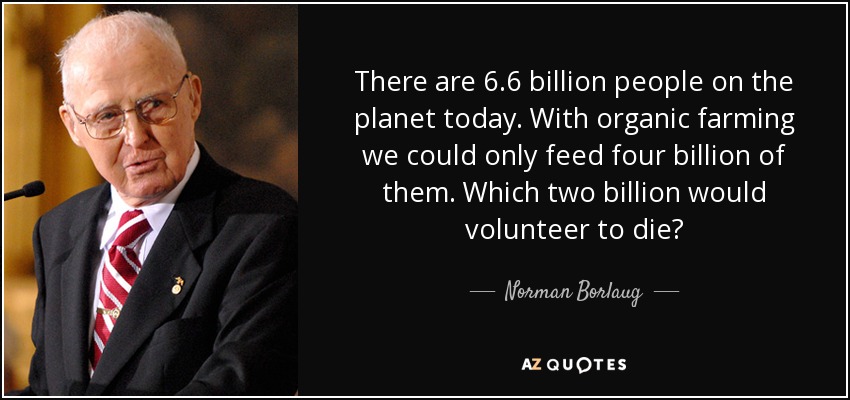

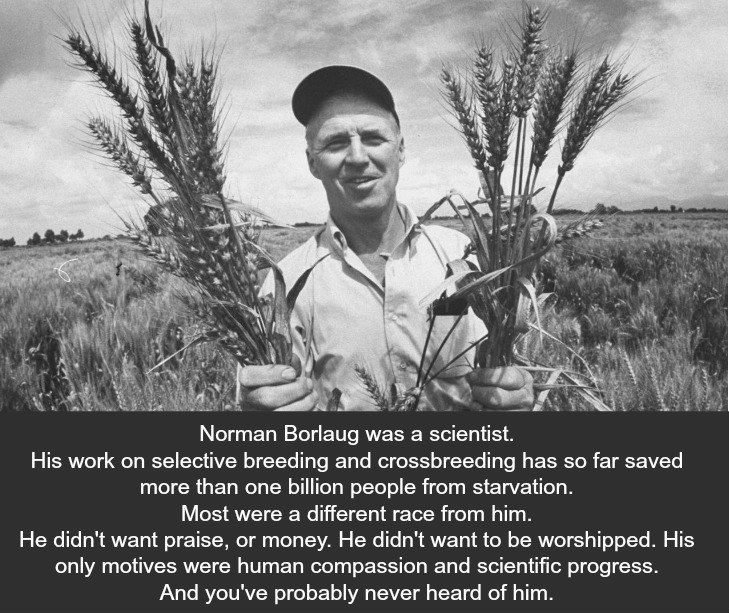

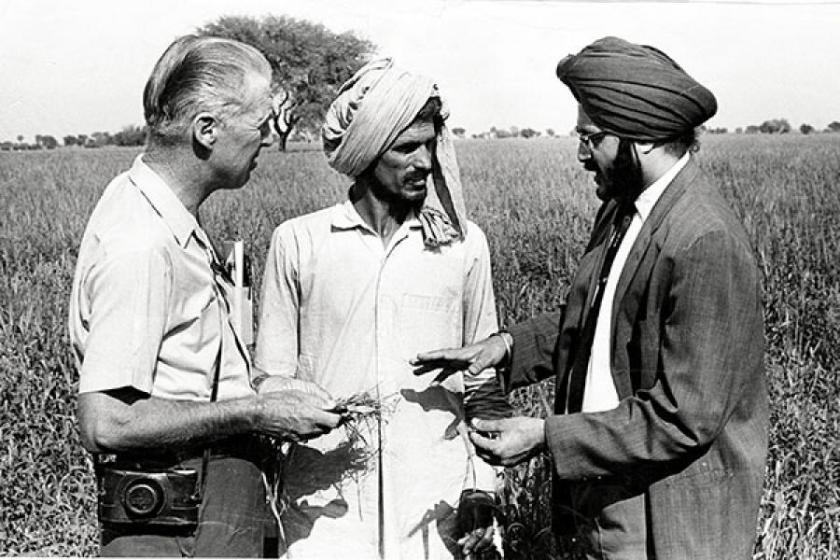

Borlaug earned his Bachelor of Science in Forestry, in 1937. Nearing the end of his undergraduate education, he attended a lecture by Professor Elvin Charles Stakman discussing plant rust disease, a parasitic fungus which feeds on phytonutrients in wheat, oats, and barley crops.

Borlaug earned his Bachelor of Science in Forestry, in 1937. Nearing the end of his undergraduate education, he attended a lecture by Professor Elvin Charles Stakman discussing plant rust disease, a parasitic fungus which feeds on phytonutrients in wheat, oats, and barley crops.

The accident began as a test, a carefully planned series of events, intending to simulate a station blackout at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, in the Soviet Socialist Republic of Ukraine.

The accident began as a test, a carefully planned series of events, intending to simulate a station blackout at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, in the Soviet Socialist Republic of Ukraine.

There was no panic, Londoners are quite accustomed to the fog, but this one was different. Over the weeks that followed, public health authorities estimated that 4,000 people had died as a direct result of the smog by December 8, and another 100,000 made permanently ill. Research pointed to another 6,000 losing their lives in the following months, as a result of the event.

There was no panic, Londoners are quite accustomed to the fog, but this one was different. Over the weeks that followed, public health authorities estimated that 4,000 people had died as a direct result of the smog by December 8, and another 100,000 made permanently ill. Research pointed to another 6,000 losing their lives in the following months, as a result of the event.

Curley was as good as his word. The Mayor and Massachusetts’ Governor Samuel McCall composed a Halifax Relief Committee to raise funds and organize aid. McCall reported the effort raised $100,000 in its first hour alone, equivalent to over $1.9 million, today.

Curley was as good as his word. The Mayor and Massachusetts’ Governor Samuel McCall composed a Halifax Relief Committee to raise funds and organize aid. McCall reported the effort raised $100,000 in its first hour alone, equivalent to over $1.9 million, today.

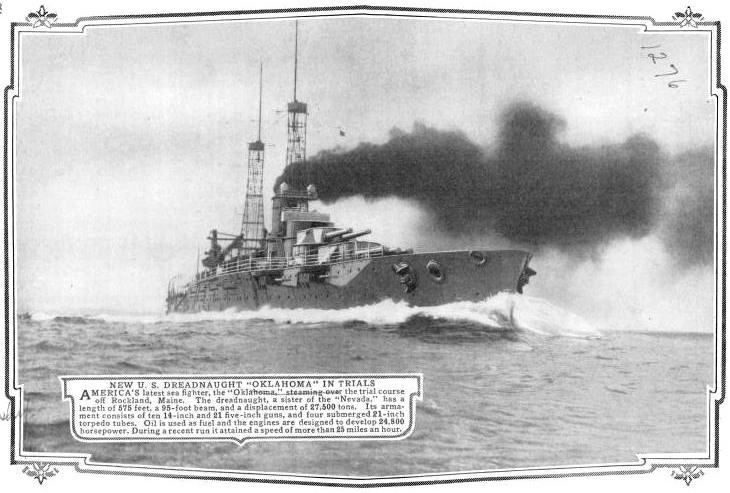

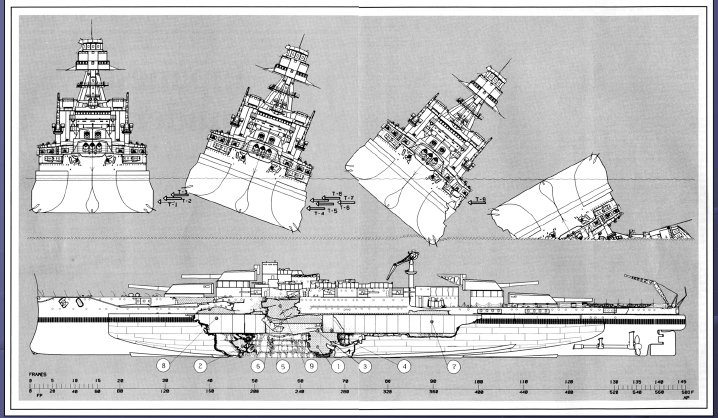

Bilge inspection plates had been removed for a scheduled inspection the following day, making counter-flooding to prevent capsize, impossible. Oklahoma rolled over and died as the ninth torpedo slammed home. Hundreds scrambled out across the rolling hull, jumped overboard into the oil covered, flaming waters of the harbor, or crawled out over mooring lines in the attempt to reach USS Maryland in the next berth.

Bilge inspection plates had been removed for a scheduled inspection the following day, making counter-flooding to prevent capsize, impossible. Oklahoma rolled over and died as the ninth torpedo slammed home. Hundreds scrambled out across the rolling hull, jumped overboard into the oil covered, flaming waters of the harbor, or crawled out over mooring lines in the attempt to reach USS Maryland in the next berth.

Recovery of the USS Oklahoma was the most complex salvage operation ever attempted, beginning in March, 1943. With the weight of her hull driving Oklahoma’s superstructure into bottom, salvage divers descended daily to separate the tower, while creating hardpoints from which to attach righting cables.

Recovery of the USS Oklahoma was the most complex salvage operation ever attempted, beginning in March, 1943. With the weight of her hull driving Oklahoma’s superstructure into bottom, salvage divers descended daily to separate the tower, while creating hardpoints from which to attach righting cables.

CDR Edward Charles Raymer, US Navy Retired, was one of those divers. Raymer tells the story of these men in

CDR Edward Charles Raymer, US Navy Retired, was one of those divers. Raymer tells the story of these men in

You must be logged in to post a comment.