Sometime around 1980, Commandant of the United States Marine Corps General Robert H. Barrow captured the nature of the art of the warrior: “Amateurs think about tactics”, he wrote, “but professionals think about logistics.” Lieutenant General Tommy Franks, Commander of the 7th Corps during Operation Desert Storm, was more to the point: “Forget logistics, you lose.”

Much is written about the history of warfare. The strategy, the tactics, and the means of supply which make it all happen. Far less has been written about a subject, equally important, if not more so. The very real service to the nation, provided by the loved ones, most often the women, when the warriors leave their homes.

In the early days of the American Revolution, Gold Selleck Silliman served as a Colonel in the Connecticut militia, later promoted to Brigadier General. Silliman patrolled the southwestern border of Connecticut, where proximity to British-occupied New York was a constant source of danger. Silliman fought with the New York campaign of 1776 and opposed the British landing in Danbury, the following year.

Mary (Fish) Noyes, the widow of John Noyes, was a strong, independent woman, of good pioneer stock. She had to be. In an age when women rarely involved themselves in the “business” side of the household, Mary’s first husband died intestate, leaving her executrix of the estate, and head of household.

Gold Selleck Silliman, himself a widower, merged his household with that of Mary on May 24, 1775, in a marriage described as “rooted in lasting friendship, deep affection, and mutual respect”. The two would have two children together, who survived into adulthood: Gold Selleck (called Sellek) born in October 1777, and Benjamin, born in August 1779.

Gold Selleck Silliman, himself a widower, merged his household with that of Mary on May 24, 1775, in a marriage described as “rooted in lasting friendship, deep affection, and mutual respect”. The two would have two children together, who survived into adulthood: Gold Selleck (called Sellek) born in October 1777, and Benjamin, born in August 1779.

Understanding that the coming Revolution could take her second husband from her as well, Mary acquainted herself with Gold’s business affairs, as well as the workings of the farm. Throughout this phase of the war, Mary Silliman ran the family farm, entertained militia officers, housed refugees of war violence, managed the labor of several slaves and that of her adult stepson, drew accounts and collected rent on her late first husband’s properties, all while her husband was away, leading the state militia.

Before the war, Gold Silliman served as Attorney for the Crown. He returned to civil life in 1777 following the Battle of Ridgefield, becoming state’s attorney.

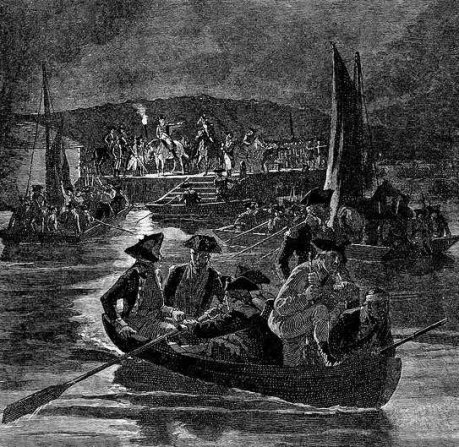

On May 2, 1779, nine Tories ostensibly under orders from General Henry Clinton, set out in a whale boat from Lloyd’s Neck on Long Island, rowing across Long Island sound and onto the Connecticut shore. One of them, a carpenter, had worked on the Silliman home and knew it well. Eight of them beat down the door in the dead of night, kidnapping Silliman and Billy, Gold’s son by his first marriage. Mary Silliman, six-months pregnant at the time, could do little but look on in horror.

The two captives were taken to Oyster Bay in New York and finally to Flatbush, and held hostage at a New York farmhouse. Patriot forces having no hostage of equal rank with whom to exchange for the General, the two Sillimans languished in captivity for seven months.

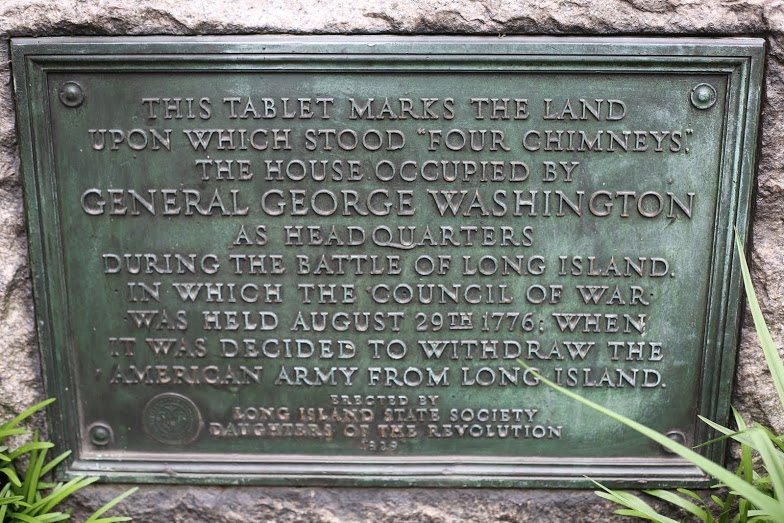

Mary Silliman wrote letters to Connecticut Governor Jonathan Trumbull, to no avail. At last, heavily pregnant, she set out for the headquarters of General George Washington himself. An aide responded that…sorry…had Silliman been kidnapped while wearing the uniform, efforts could be made to intercede. As it was, the captive was a civilian. He was on his own.

Mary was left to run the farm, including caring for her own midwife, after the woman was brutally raped during a lighting raid in which English forces burned family buildings and crops, along with much of Ridgefield. All the while, Mary herself wanted nothing more than the return of her husband, and to become “the living mother of a living child”.

With all other options exhausted, Mary contracted the services of one David Hawley, a full-time Naval Captain and part-time privateer. Hawley staged a daring raid of his own, rowing across the sound and kidnapping a man suitable for exchange with Gold Silliman, in the person of Chief Justice Thomas Jones, of Long Island.

British authorities balked at the exchange and the stalemate dragged on for months. In the end, Mary Silliman got her wish, becoming the living mother of a living child that August. Gold Selleck and Billy Silliman were exchanged the following May, for Judge Jones.

The 1993 made-for-TV movie “Mary Silliman’s War” tells a story of non-combatants in the American Revolution. The pregnant mothers and farm wives, as well as Silliman’s own negotiations for her husband’s release, by his Loyalist captors. The film is outstanding, the history straight-up and unadulterated with pop culture nonsense, as far as I can tell. The film is available for download, I found it for nine bucks. It was nine dollars, well spent.

Feature image, top of page: Silliman house, ca. 1890

Two years later, Patriot forces maintained a similar supply depot, in the southwest Connecticut town of Danbury.

Two years later, Patriot forces maintained a similar supply depot, in the southwest Connecticut town of Danbury.

Mary Silliman was left to run the farm, and negotiate for the release of her husband. The 1993 made-for-TV movie “Mary Silliman’s War” tells a story of non-combatants, pregnant mothers and farm wives, during the Revolution.

Mary Silliman was left to run the farm, and negotiate for the release of her husband. The 1993 made-for-TV movie “Mary Silliman’s War” tells a story of non-combatants, pregnant mothers and farm wives, during the Revolution.

In those days, Boston was a virtual island, connected to the mainland by a narrow “neck” of land. More than 20,000 armed men converged from all over New England in the weeks that followed, gathering in buildings and encampments from Cambridge to Roxbury.

In those days, Boston was a virtual island, connected to the mainland by a narrow “neck” of land. More than 20,000 armed men converged from all over New England in the weeks that followed, gathering in buildings and encampments from Cambridge to Roxbury.

An unnamed British military officer felt the need to run his mouth before the Parliament, at the expense of his fellow British subjects in the American colonies. “Americans are unequal to the People of this Country”, he said, “in Devotion to Women, and in Courage, and worse than all, they are religious”.

An unnamed British military officer felt the need to run his mouth before the Parliament, at the expense of his fellow British subjects in the American colonies. “Americans are unequal to the People of this Country”, he said, “in Devotion to Women, and in Courage, and worse than all, they are religious”.

Sint Eustatius, known to locals as “Statia”, is a Caribbean island of 8.1 sq. miles in the northern Leeward Islands. Formerly part of the Netherlands Antilles, the island lies southeast of the Virgin Islands, immediately to the northwest of Saint Kitts.

Sint Eustatius, known to locals as “Statia”, is a Caribbean island of 8.1 sq. miles in the northern Leeward Islands. Formerly part of the Netherlands Antilles, the island lies southeast of the Virgin Islands, immediately to the northwest of Saint Kitts.

On the 16th of November, 1776, the Brig Andrew Doria sailed into Sint Eustatius’ principle anchorage in Oranje Bay. Flying the Continental Colors of the fledgling United States and commanded by Captain Isaiah Robinson, the Brig was there to obtain munitions and military supplies. Andrew Doria also carried a precious cargo, a copy of the Declaration of Independence.

On the 16th of November, 1776, the Brig Andrew Doria sailed into Sint Eustatius’ principle anchorage in Oranje Bay. Flying the Continental Colors of the fledgling United States and commanded by Captain Isaiah Robinson, the Brig was there to obtain munitions and military supplies. Andrew Doria also carried a precious cargo, a copy of the Declaration of Independence. Tradition dictated the firing of a salute in return, typically two guns fewer than that fired by the incoming vessel. Such an act carried meaning. The firing of a return salute was the overt recognition that a sovereign state had entered the harbor. Such a salute amounted to formal recognition of the independence of the 13 American colonies.

Tradition dictated the firing of a salute in return, typically two guns fewer than that fired by the incoming vessel. Such an act carried meaning. The firing of a return salute was the overt recognition that a sovereign state had entered the harbor. Such a salute amounted to formal recognition of the independence of the 13 American colonies. Rodney pretty much had his way. The census of 1790 shows 8,124 on the Dutch island nation. In 1950, the population stood at 790. It would take 150 years from Rodney’s departure, before tourism even began to restore the economic well-being of the tiny island.

Rodney pretty much had his way. The census of 1790 shows 8,124 on the Dutch island nation. In 1950, the population stood at 790. It would take 150 years from Rodney’s departure, before tourism even began to restore the economic well-being of the tiny island.

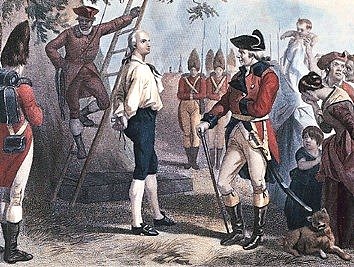

Washington asked for volunteers for a dangerous mission, to go behind enemy lines, as a spy. Up stepped a volunteer. His name was Nathan Hale.

Washington asked for volunteers for a dangerous mission, to go behind enemy lines, as a spy. Up stepped a volunteer. His name was Nathan Hale. Hale took Rogers into his confidence, believing the two to be playing for the same side. Barkhamsted Connecticut shopkeeper Consider Tiffany, a British loyalist and himself a sergeant of the French and Indian War, recorded what happened next, in his journal: “The time being come, Captain Hale repaired to the place agreed on, where he met his pretended friend” (Rogers), “with three or four men of the same stamp, and after being refreshed, began [a]…conversation. But in the height of their conversation, a company of soldiers surrounded the house, and by orders from the commander, seized Captain Hale in an instant. But denying his name, and the business he came upon, he was ordered to New York. But before he was carried far, several persons knew him and called him by name; upon this he was hanged as a spy, some say, without being brought before a court martial.”

Hale took Rogers into his confidence, believing the two to be playing for the same side. Barkhamsted Connecticut shopkeeper Consider Tiffany, a British loyalist and himself a sergeant of the French and Indian War, recorded what happened next, in his journal: “The time being come, Captain Hale repaired to the place agreed on, where he met his pretended friend” (Rogers), “with three or four men of the same stamp, and after being refreshed, began [a]…conversation. But in the height of their conversation, a company of soldiers surrounded the house, and by orders from the commander, seized Captain Hale in an instant. But denying his name, and the business he came upon, he was ordered to New York. But before he was carried far, several persons knew him and called him by name; upon this he was hanged as a spy, some say, without being brought before a court martial.” There is no official account of Nathan Hale’s final words, but we have an eyewitness statement from British Captain John Montresor, who was present at the hanging.

There is no official account of Nathan Hale’s final words, but we have an eyewitness statement from British Captain John Montresor, who was present at the hanging.

Several measures were taken in the 1760’s to collect these revenues. In one 12-month period, Parliament passed the Stamp Act, the Quartering Act, and the Declaratory Act, and deputized the Royal Navy’s Sea Officers to help enforce customs laws in colonial ports.

Several measures were taken in the 1760’s to collect these revenues. In one 12-month period, Parliament passed the Stamp Act, the Quartering Act, and the Declaratory Act, and deputized the Royal Navy’s Sea Officers to help enforce customs laws in colonial ports.

A few days later, a visiting minister in Boston, John Allen, used the Gaspée incident in a 2nd Baptist Church sermon. His sermon was printed seven times in four colonial cities, one of the most widely read pamphlets in Colonial British America.

A few days later, a visiting minister in Boston, John Allen, used the Gaspée incident in a 2nd Baptist Church sermon. His sermon was printed seven times in four colonial cities, one of the most widely read pamphlets in Colonial British America.

You must be logged in to post a comment.