Born May 5, 1864, Elizabeth Jane Cochran was one of fifteen children born to Michael Cochran, and two wives. Michael died in 1870 leaving a modest legacy. It didn’t amount to much, split fifteen ways.

As a teenager in western Pennsylvania, Elizabeth adopted an “e” believing that “Cochrane” sounded more sophisticated. She enrolled at the Indiana Normal School in 1879 (now Indiana University of Pennsylvania) but dropped out after one semester, for lack of funds. In 1880 her mother moved the family, to Pittsburgh.

According to an article in the Pittsburg Dispatch entitled “What girls are for” the answer appears to be, not very much. Making babies and keeping house. Elizabeth didn’t appreciate that and wrote to the paper, to say so. She signed her letter, “Lonely Orphan Girl”.

If writing well is the sign of an organized thought process, the mind of Elizabeth Cochrane was in good working order. Impressed with the anonymous letter, Editor George Madden ran an advertisement asking that the writer, identify herself.

That she did. Madden offered the opportunity to write a piece for publication, under the same pseudonym. Cochrane called that first piece “The Girl Puzzle”, describing how divorce effected women and arguing for reform of marital laws.

Madden was even more impressed and hired Elizabeth, full-time. In those days, women who wrote for newspapers generally did so, under a pseudonym. The Editor suggested “Nelly Bly” after the subject of a popular minstrel song, from 1850. Cochrane liked “Nelly” but her editor spelled it with an ‘ie’.

Nellie Bly would go on to be one of the most famous journalists of the age.

She first came to widespread notice with a series of investigative articles, focused on poor working conditions and the plight of female factory workers. Factory owners complained. Bly was reassigned to a role more typical of female reporters: Gardening. Society. Fashion.

She didn’t want any of it. Still only 21, she wanted “to do something no girl has done before.” She traveled to Mexico and became a foreign correspondent, writing about the Mexican people and criticizing the dictatorship, of President Porfirio Diaz.

Stung by what she had written, Mexican authorities threatened to throw her in jail. Bly was forced to flee. Back in Pittsburg, it wasn’t long before she’d had enough of theater and arts reporting. She resigned her job in 1887 and moved to New York.

This was the age of lurid headlines, of sensational if not always accurate stories and homeless street waifs called “Newsies“, hawking newspapers: “Extra Extra, read all about it!” Within the next five years, San Francisco publisher William Randolph Hearst would buy crosstown rival New York Journal sparking a newspaper war and a new style of news we now call “Yellow Journalism“.

Penniless after four months without income, Cochrane walked into the office of New York World publisher, Joseph Pulitzer. Pulitzer had purchased the company four years earlier promising to root out corruption, expose fraud and ferret out public abuse, at all levels.

Bly was hired to cover theater and the arts but the pair soon concocted an undercover assignment. Nellie Bly would feign insanity, with the aim of being committed to the notorious women’s insane asylum on Blackwell’s Island.

It was a dangerous ruse but it worked. The “pretty crazy girl” fooled the New York press and mental health “experts” alike, culminating in Bly’s incarceration at Blackwell’s Island. She was released at the behest of the New York World, ten days later.

Bly’s exposé was a sensation. First in a series of stories and then in a book entitled Ten Days in a Madhouse, Nellie Bly told tales of torture, of ice cold baths in used and filthy water, rancid food and the rats, vermin and brutality suffered by women she was convinced were every bit as sane, as herself.

Public outrage prompted a grand jury investigation culminating in an $800,000 increase in public funding to the Department of Public Charities and Corrections.

Bly’s caper sparked a new form of “stunt journalism”, a new breed of female reporters with secret identities like “Florence Noble” and “Dorothy Dare” tackling subjects like disaster victims, the plight of factory workers and other subjects previously considered “unfit for ladies”.

Every major newspaper in the nation wanted a “stunt girl” on the staff.

In 1872, novelist Jules Verne published the fictional tale of the gambler Phileas Fogg and the trip he went on, to win a bet. The story was called Around the World in 80 Days. In 1888, Nellie Bly pitched the same trip to her editor. For real.

With two days’ notice, Nellie Bly boarded the Hamburg America Line steamer Augusta Victoria in November 1889 to begin her 25,000-mile adventure. She took an overcoat, the dress she was wearing, a few changes of underwear and a travel bag with a few essentials. A bag with £200 in English bank notes, some gold and American currency hung around her neck.

Unknown to Nellie at this time, Cosmopolitan magazine was sponsoring reporter Elizabeth Bisland to take the same trip, in the opposite direction.

She departed the same day.

New underwater cables enabled Bly to send short progress reports though longer dispatches had to travel by mail. From her first stop in England she traveled to France where she met Jules Verne himself and on to Brindisi, the Suez Canal, Ceylon and the Far East. She visited a leper colony in China. In Singapore, she bought a monkey.

The New York World sponsored a “Nellie Bly Guessing Match”. Who could predict to the second, the journalist’s return. The grand prize was an all-expense paid trip to Europe. Spending money was tossed in, later on. A rough Pacific passage on board the Steamer RMS Oceanic put the trip two days behind schedule but Pulitzer’s newspaper made that up, hiring a private train from San Francisco.

Nellie Bly arrived in New York on January 25, 1890 at 3:51pm, besting Phileas Fogg’s time, by eight days. Over at Cosmo, Bisland was still crossing the Atlantic, with 4½ days to go.

At 31, Nellie Bly married 73-year old metal container manufacturer Robert Seaman in 1895, and left journalism. Seaman died in 1904 and, for a time, Elizabeth was one of the leading female industrialists, in the country.

She ran the company as “a model of social welfare, replete with health benefits and recreational facilities“, according to biographer, Brooke Kroeger.

“But Bly was hopeless at understanding the financial aspects of her business and ultimately lost everything. Unscrupulous employees bilked the firm of hundreds of thousands of dollars, troubles compounded by a protracted and costly bankruptcy litigation“.

Back in journalism, Bly traveled to Europe to cover the Great War. She was the first woman and one of few foreigners to visit the war zone between Austria, and Serbia.

In 1913, Nelly Bly covered the first suffragist parade in Washington. She predicted women would have the vote, by 1920.

The 19th Amendment giving (white) women the vote was certified on August 26, 1920, by US Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby.

In practice, voting restrictions against non-white men now extended to non-white women. The crusade to protect the voting rights of ALL American citizens would last, another 40 years.

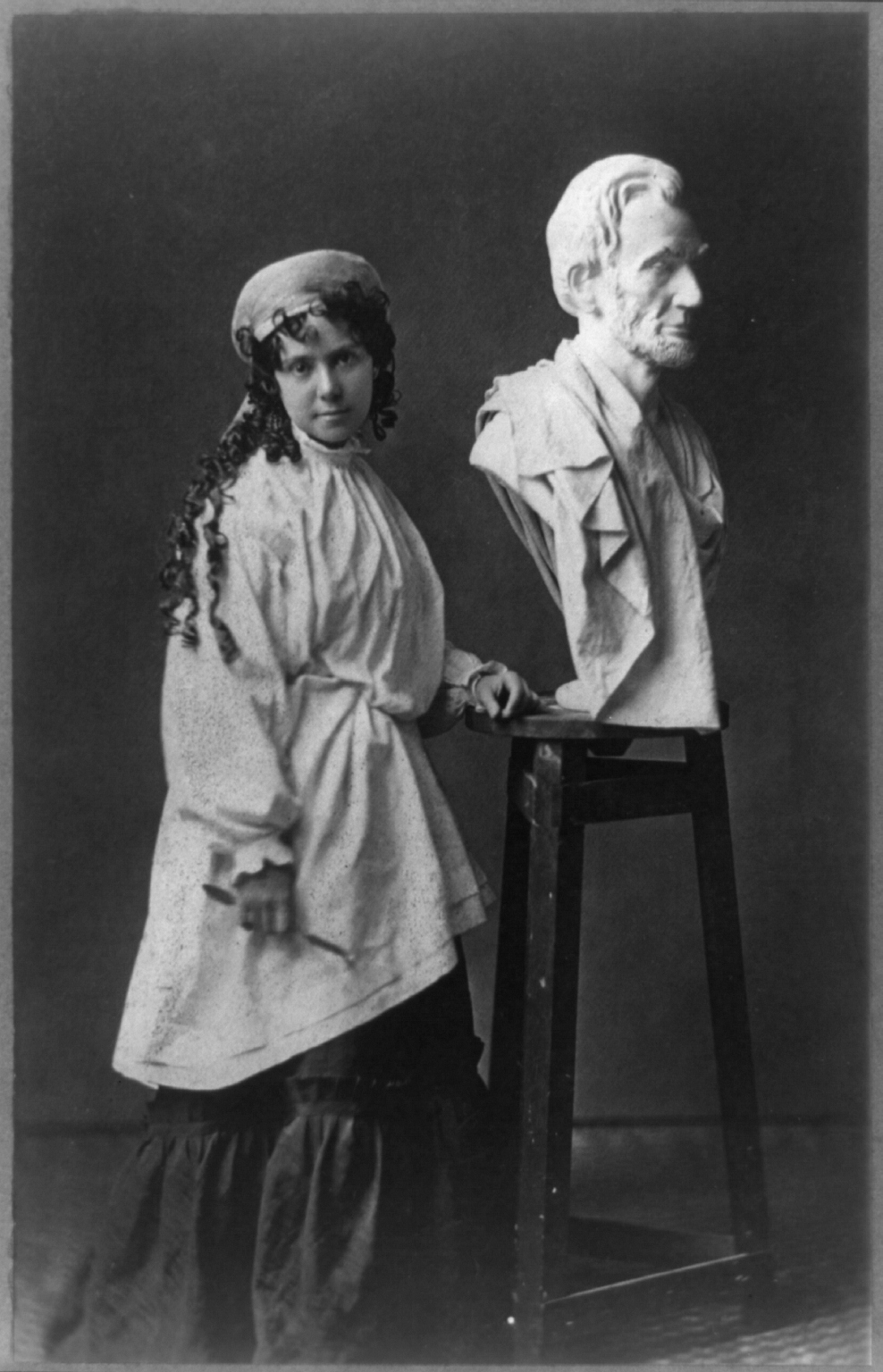

Then as now, Washington was a “Swamp” and a cesspit for the venal and self-interested. Now grown to an attractive young woman, Vinnie Ream was not without critics. Kansas Senator Edmund Gibson Ross boarded with the Ream family during Johnson’s impeachment trial and cast the one vote absolving the President of “High Crimes and Misdemeanors”.

Then as now, Washington was a “Swamp” and a cesspit for the venal and self-interested. Now grown to an attractive young woman, Vinnie Ream was not without critics. Kansas Senator Edmund Gibson Ross boarded with the Ream family during Johnson’s impeachment trial and cast the one vote absolving the President of “High Crimes and Misdemeanors”. One editor had the last word, however, printing Swisshelm’s column under the headline “A Homely Woman’s Opinion of a Pretty One.”

One editor had the last word, however, printing Swisshelm’s column under the headline “A Homely Woman’s Opinion of a Pretty One.”

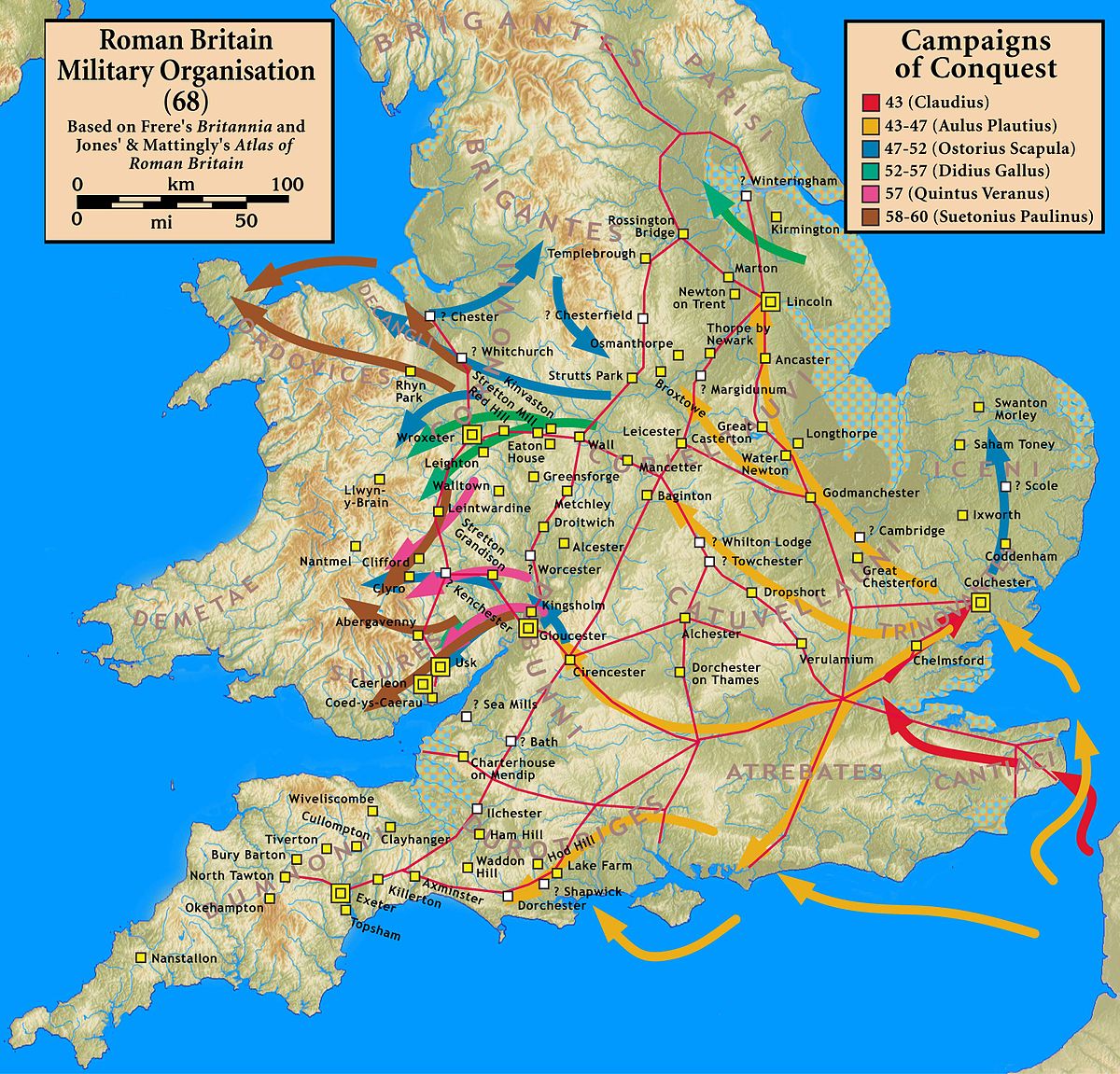

In the Roman imagination, Britain was a faraway and exotic place, a misty, forested land inhabited by fierce, blue painted warriors.

In the Roman imagination, Britain was a faraway and exotic place, a misty, forested land inhabited by fierce, blue painted warriors. Militarily, there was no reason to attack the British home isles. The channel itself formed as fine a protector of the western flank, as could be hoped for.

Militarily, there was no reason to attack the British home isles. The channel itself formed as fine a protector of the western flank, as could be hoped for.

Apoplectic with rage and determined to avenge her family, Boudicca was not a woman to be trifled with. She led the Iceni, the Trinovantes and others among the Celtic, pre-Roman peoples of Britain, in a full-scale, bloody revolt.

Apoplectic with rage and determined to avenge her family, Boudicca was not a woman to be trifled with. She led the Iceni, the Trinovantes and others among the Celtic, pre-Roman peoples of Britain, in a full-scale, bloody revolt. For the Celtic peoples, the hour of payback had arrived. For the seizure of lands to provide estates for Roman veterans to their own forced labor in building the Temple of Claudius to the sudden recall of loans and destruction of estates and properties. The Roman historian Tacitus writes of the last stand at the Temple of Claudius: “In the attack everything was broken down and burnt. The temple where the soldiers had congregated was besieged for two days and then sacked“.

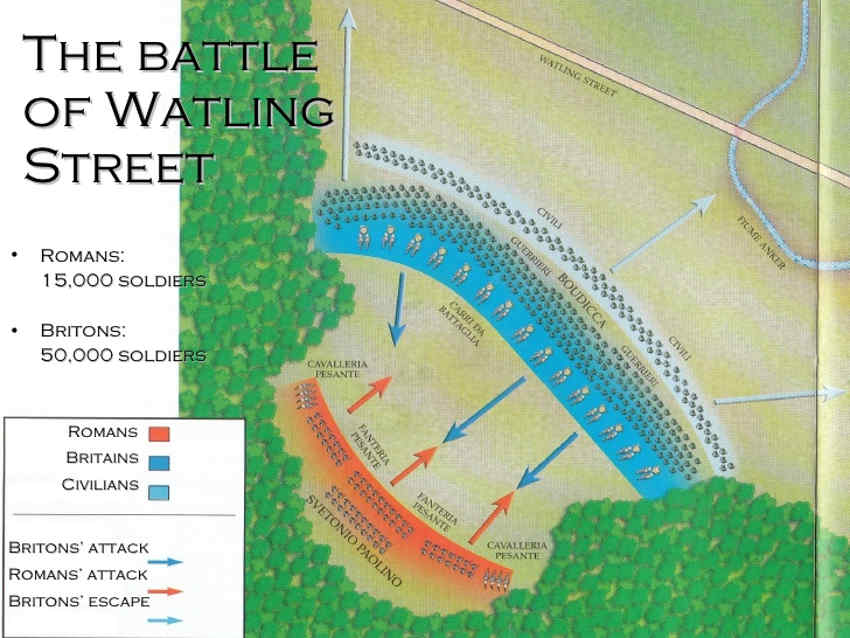

For the Celtic peoples, the hour of payback had arrived. For the seizure of lands to provide estates for Roman veterans to their own forced labor in building the Temple of Claudius to the sudden recall of loans and destruction of estates and properties. The Roman historian Tacitus writes of the last stand at the Temple of Claudius: “In the attack everything was broken down and burnt. The temple where the soldiers had congregated was besieged for two days and then sacked“. Outnumbered 23 to 1, the 10,000 strong Roman legion was battle hardened, well-equipped and disciplined, facing off against a mob of nearly a quarter-million unarmored, poorly disciplined individuals.

Outnumbered 23 to 1, the 10,000 strong Roman legion was battle hardened, well-equipped and disciplined, facing off against a mob of nearly a quarter-million unarmored, poorly disciplined individuals. What must it look like, when 230,000 screaming warriors charge a fixed force of 10,000 disciplined soldiers. First came the Pila, the Roman javelins tearing into the tightly packed front, of the adversary. Then the Legion advanced, shields out front with the short swords, the long swords and farm implements of the Celts unable to move in the crush of humanity. The wedge formation advanced unbroken, slaughtering all who came before it as a scythe before the grass. The turning and the attempt to flee, only to be boxed in by their own tightly packed crescent formed wagon train.

What must it look like, when 230,000 screaming warriors charge a fixed force of 10,000 disciplined soldiers. First came the Pila, the Roman javelins tearing into the tightly packed front, of the adversary. Then the Legion advanced, shields out front with the short swords, the long swords and farm implements of the Celts unable to move in the crush of humanity. The wedge formation advanced unbroken, slaughtering all who came before it as a scythe before the grass. The turning and the attempt to flee, only to be boxed in by their own tightly packed crescent formed wagon train. 80,000 of Boudicca’s men lay dead before the slaughter was ended, against 400 dead Romans. Queen Boudicca poisoned herself according to Tacitus, Cassius Dio claims she became ill.

80,000 of Boudicca’s men lay dead before the slaughter was ended, against 400 dead Romans. Queen Boudicca poisoned herself according to Tacitus, Cassius Dio claims she became ill.

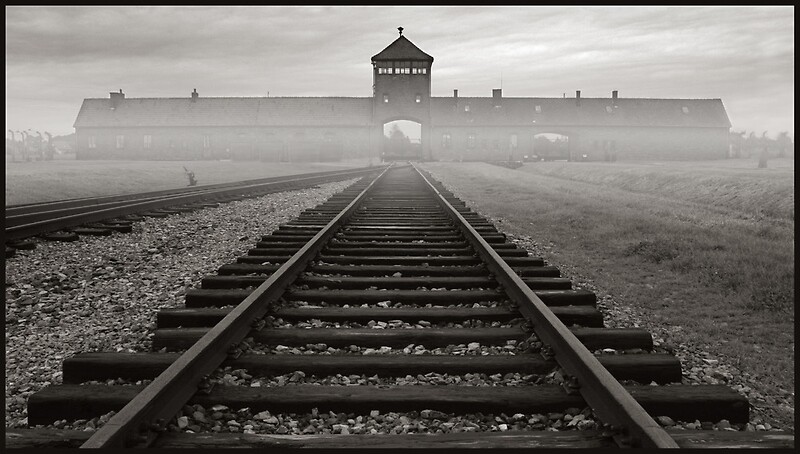

Circus-like performing dwarves were common enough at this time but the Ovitz siblings were different. These were talented musicians playing quarter-sized instruments, performing a variety show throughout the 1930s and early ’40s as the “Lilliput Troupe”. The family performed throughout Romania, Hungary and Czechoslovakia, with their normal height siblings serving as “roadies”. And then came the day. The whole lot of them were swept up by the Nazis and deported to the concentration camp and extermination center, at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Circus-like performing dwarves were common enough at this time but the Ovitz siblings were different. These were talented musicians playing quarter-sized instruments, performing a variety show throughout the 1930s and early ’40s as the “Lilliput Troupe”. The family performed throughout Romania, Hungary and Czechoslovakia, with their normal height siblings serving as “roadies”. And then came the day. The whole lot of them were swept up by the Nazis and deported to the concentration camp and extermination center, at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

On one occasion, the Angel of Death told the family they were “going to a beautiful place”. Terrified, the siblings were given makeup, and told to dress themselves. Brought to a nearby theater and placed onstage, the family must have thought they’d be asked to perform. Instead, Mengele ordered them to undress, leaving all seven naked before a room full of SS men. Mengele then gave a speech and invited the audience onstage, to poke and prod at the humiliated family.

On one occasion, the Angel of Death told the family they were “going to a beautiful place”. Terrified, the siblings were given makeup, and told to dress themselves. Brought to a nearby theater and placed onstage, the family must have thought they’d be asked to perform. Instead, Mengele ordered them to undress, leaving all seven naked before a room full of SS men. Mengele then gave a speech and invited the audience onstage, to poke and prod at the humiliated family.

Only 50 of the 650 Jewish inhabitants of the village ever returned. In 1949, the family emigrated to Israel and resumed their musical tour, performing until the group retired in 1955.

Only 50 of the 650 Jewish inhabitants of the village ever returned. In 1949, the family emigrated to Israel and resumed their musical tour, performing until the group retired in 1955.

The earliest discernible Mother’s day dates back to 1200-700BC and descending from the Phrygian rituals of modern day Turkey and Armenia. “Cybele” was the great Phrygian goddess of nature, mother of the Gods, of humanity, and of all the beasts of the natural world, her cult spreading throughout Eastern Greece with colonists from Asia Minor.

The earliest discernible Mother’s day dates back to 1200-700BC and descending from the Phrygian rituals of modern day Turkey and Armenia. “Cybele” was the great Phrygian goddess of nature, mother of the Gods, of humanity, and of all the beasts of the natural world, her cult spreading throughout Eastern Greece with colonists from Asia Minor. In the sixteenth century, it became popular for Protestants and Catholics alike to return to their “mother church” whether that be the church of their own baptism, the local parish church, or the nearest cathedral. Anyone who did so was said to have gone “a-mothering”. Domestic servants were given the day off and this “Mothering Sunday”, the 4th Sunday in Lent, was often the only time when whole families could get together. Children would gather wild flowers along the way, to give to their own mothers or to leave in the church. Over time the day became more secular, but the tradition of gift giving continued.

In the sixteenth century, it became popular for Protestants and Catholics alike to return to their “mother church” whether that be the church of their own baptism, the local parish church, or the nearest cathedral. Anyone who did so was said to have gone “a-mothering”. Domestic servants were given the day off and this “Mothering Sunday”, the 4th Sunday in Lent, was often the only time when whole families could get together. Children would gather wild flowers along the way, to give to their own mothers or to leave in the church. Over time the day became more secular, but the tradition of gift giving continued.

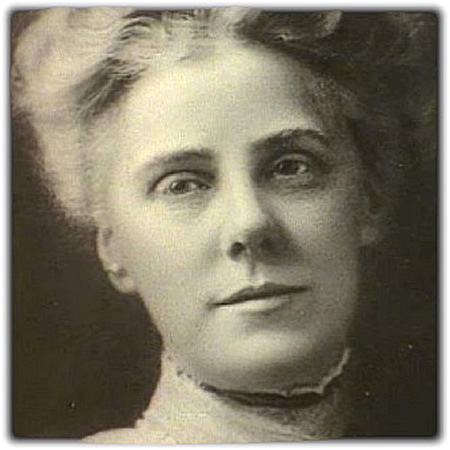

Ann Maria Reeves Jarvis was a social activist in mid-19th century western Virginia. Pregnant with her sixth child in 1858, she and other women formed “Mothers’ Day Work Clubs”, to combat the health and sanitary conditions leading at that time to catastrophic levels of infant mortality. Jarvis herself gave birth between eleven and thirteen times in a seventeen year period.

Ann Maria Reeves Jarvis was a social activist in mid-19th century western Virginia. Pregnant with her sixth child in 1858, she and other women formed “Mothers’ Day Work Clubs”, to combat the health and sanitary conditions leading at that time to catastrophic levels of infant mortality. Jarvis herself gave birth between eleven and thirteen times in a seventeen year period. Following Jarvis’ death in 1905, her daughter Anna conceived of Mother’s Day as a way to honor her legacy and to pay respect for the sacrifices made by all mothers, on behalf of their children.

Following Jarvis’ death in 1905, her daughter Anna conceived of Mother’s Day as a way to honor her legacy and to pay respect for the sacrifices made by all mothers, on behalf of their children.

This story is dedicated to two of the most beautiful women in my life. Ginny Long, thanks Mom, for not throttling me all those times you could have. And most especially, for all those times when you SHOULD have. Sheryl Kozens Long, thanks for 25 great years. Rest in peace, sugar. I wish you didn’t have to leave us, quite so soon.

This story is dedicated to two of the most beautiful women in my life. Ginny Long, thanks Mom, for not throttling me all those times you could have. And most especially, for all those times when you SHOULD have. Sheryl Kozens Long, thanks for 25 great years. Rest in peace, sugar. I wish you didn’t have to leave us, quite so soon.

You must be logged in to post a comment.