Today, Cabanatuan calls itself the “Tricycle Capital of the Philippines”, with about 30,000 motorized “auto rickshaws”. 72 years ago, it was home to one of the worst POW camps of WWII.

1942 was a bad year for the allied war in the Pacific. The Battle of Bataan alone resulted in 72,000 prisoners being taken by the Japanese, marched off to POW camps designed for 10,000 to 25,000.

1942 was a bad year for the allied war in the Pacific. The Battle of Bataan alone resulted in 72,000 prisoners being taken by the Japanese, marched off to POW camps designed for 10,000 to 25,000.

20,000 of them died from sickness or hunger, or were murdered by Japanese guards on the 60 mile “death march” from Bataan, into captivity at Cabanatuan prison and others.

Cabanatuan held 8,000 prisoners at its peak, though the number dropped considerably as the able-bodied were shipped out to work in Japanese slave labor camps.

Two rice rations per day, fewer than 800 calories, were supplemented by the occasional animal or insect caught and killed inside camp walls, or by the rare food items smuggled in by civilian visitors. 2,400 died in the first eight months at Cabanatuan, animated skeletons brought to “hospital wards”, which were nothing more than 2’x6′ patches of floor where prisoners waited to die. A Master Sergeant Gaston saw one of these wards in July 1942, saying: “The men in the ward were practically nothing but skin and bones and they had open ulcers on their hips, on their knees and on their shoulders…maggots were eating on the open wounds. There were blow flies…by the millions…men were unable to get off the floor to go to the latrine and their bowels moved as they lay there”.

The war was going badly for the Japanese by October 1944, as Imperial Japanese High Command ordered able bodied POWs removed to Japan. 1,600 were taken from Cabanatuan, leaving 500 weak and disabled prisoners. The guards abandoned camp shortly after, though Japanese soldiers continued to pass through. POWs were able to steal food from abandoned Japanese quarters; some even captured two water buffalo called “Carabao”, which were killed and eaten. Many feared a trick and never dared to leave the camp. Most were too sick and weak to leave in any case, though the extra rations would help them through what was to come.

On December 14, units of the Japanese Fourteenth Area Army in Palawan doused 150 prisoners with gasoline and burned them alive, machine gunning any who tried to escape the flames. The atrocity sparked a series of raids at Santo Tomas Internment Camp, Bilibid Prison, Los Baños and others. The first such behind-enemy-lines rescue, was Cabanatuan.

On the evening of January 27, 1945, 14 individuals separated into two teams, beginning the 30 mile march behind enemy lines to liberate Cabanatuan. They were an advance team, formed from the 6th Ranger Battalion and a special reconnaissance group called the Alamo Scouts. The main force of 121 Rangers moved out the following day, meeting up with 200 Filipino guerrillas, who served as guides and helped in the rescue.

Other guerrillas assisted along the way, muzzling dogs and corralling chickens so that Japanese occupiers would hear nothing of their approach. Japanese soldiers once again occupied the camp, with 1,000 more camped across the Cabo River outside the prison and as many as 7,000 deployed just a few miles away.

On the night of the 30th, a P-61 Black Widow piloted by Captain Kenneth Schrieber and 1st Lt. Bonnie Rucks staged a ruse. For 45 minutes, the pair conducted a series of aerial acrobatics, cutting and restarting engines with loud backfires while seeming to struggle to maintain altitude. Thousands of Japanese soldiers watched the show, as Rangers belly crawled into positions around the camp.

Guard towers and pillboxes were wiped out in the first fifteen seconds of the assault. Filipino guerrillas blew the bridge and ambushed the large force across the river while one, trained to use a bazooka only hours earlier, took out four Japanese tanks.

In the camp, all was pandemonium as some prisoners came out and others hid, suspecting some trick to bring them out into the open. They were so emaciated that Rangers carried them out two at a time.

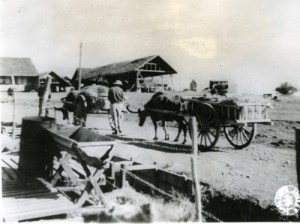

The raid was over in 35 minutes, POWs brought to pre-arranged meet-up places with dozens of carabao carts. A long trek yet remained, one POW said “I made the Death March from Bataan, so I can certainly make this one!” Over three days, up to 106 carts joined the procession, their plodding 2 MPH progress covered by strafing American aircraft.

Two American Rangers and two prisoners were killed, another 4 Americans and 21 Filipinos wounded, compared with 500-1,000 Japanese killed and four tanks put out of action. 464 American military personnel were liberated, along with 22 British and 3 Dutch soldiers, 28 American civilians, 2 Norwegians and one civilian each of British, Canadian and Filipino nationalities.

One POW was left behind, a British soldier named Edwin Rose. Rose heard the firing and thought the Americans were there to stay, so he went back to sleep. When he woke the next morning and realized he had “Cabanatuan all my own”, he shaved, put on his best clothes, and walked out of camp. Passing guerrillas found him and passed him to a tank destroyer. Give the man points for style. A few days later, Rose strolled into 6th army headquarters, a cane tucked under his arm.

The Cabanatuan raid of January 30, 1945 liberated over 500 allied prisoners, from virtually every state in the Union. Begging pardon for any mistakes in rank and/or spelling, the following represents those from my home state of Massachusetts:

- Lieutenant Commander Robert Strong, Jr., Arlington

- Captain John Dugan, Milton

- 2nd Lieutenant John Temple, Pittsfield

- Sergeant Richard Neault, Adams

- Sergeant Stanislaus Malor, Salem

- Private, 1st Class Joseph Thibeault, Lawrence

- Private Edward Searkey, Lynn

- USN C/QM Martin Seliga, Fitchburg

- USN 1/C PO J.E.A. Morin,Danvers

- USN AC MM Carl Silverman, Wareham

I hope I didn’t leave anyone out. These guys have earned the right to be remembered.

Joining the 3rd Infantry Division of George S. Patton’s 7th Army, Murphy participated in amphibious landings in Sicily in July, fighting in nearly every aspect of the Italian campaign. From Palermo to Messina and on to Naples, Anzio and Rome, the Germans were driven out of the Italian peninsula in savage and near continuous fighting that killed a member of my own family. By mid-December, the 3rd ID suffered 683 dead, 170 missing, and 2,412 wounded. Now Sergeant Murphy was there for most of it, excepting two periods when he was down with malaria.

Joining the 3rd Infantry Division of George S. Patton’s 7th Army, Murphy participated in amphibious landings in Sicily in July, fighting in nearly every aspect of the Italian campaign. From Palermo to Messina and on to Naples, Anzio and Rome, the Germans were driven out of the Italian peninsula in savage and near continuous fighting that killed a member of my own family. By mid-December, the 3rd ID suffered 683 dead, 170 missing, and 2,412 wounded. Now Sergeant Murphy was there for most of it, excepting two periods when he was down with malaria. “Colmar Pocket” was an 850 square mile area held by German troops: Murphy described it as “a huge and dangerous bridgehead thrusting west of the Rhine like an iron fist. Fed with men and materiel from across the river, it is a constant threat to our right flank; and potentially it is a perfect springboard from which the enemy could start a powerful counterattack.”

“Colmar Pocket” was an 850 square mile area held by German troops: Murphy described it as “a huge and dangerous bridgehead thrusting west of the Rhine like an iron fist. Fed with men and materiel from across the river, it is a constant threat to our right flank; and potentially it is a perfect springboard from which the enemy could start a powerful counterattack.” Let Murphy’s Medal of Honor Citation describe what happened next: “Second Lieutenant Audie L. Murphy, 01692509, 15th Infantry, Army of the United States, on 26 January 1945, near Holtzwihr, France, commanded Company B, which was attacked by six tanks and waves of infantry. Lieutenant Murphy ordered his men to withdraw to a prepared position in a woods while he remained forward at his command post and continued to give fire directions to the artillery by telephone. Behind him to his right one of our tank destroyers received a direct hit and began to burn. Its crew withdrew to the woods. Lieutenant Murphy continued to direct artillery fire which killed large numbers of the advancing enemy infantry. With the enemy tanks abreast of his position, Lieutenant Murphy climbed on the burning tank destroyer which was in danger of blowing up any instant and employed its .50 caliber machine gun against the enemy. He was alone and exposed to the German fire from three sides, but his deadly fire killed dozens of Germans and caused their infantry attack to waver. The enemy tanks, losing infantry support, began to fall back. For an hour the Germans tried every available weapon to eliminate Lieutenant Murphy, but he continued to hold his position and wiped out a squad which was trying to creep up unnoticed on his right flank. Germans reached as close as 10 yards only to be mowed down by his fire. He received a leg wound but ignored it and continued the single-handed fight until his ammunition was exhausted. He then made his way to his company, refused medical attention, and organized the company in a counterattack which forced the Germans to withdraw. His directing of artillery fire wiped out many of the enemy; he personally killed or wounded about 50. Lieutenant Murphy’s indomitable courage and his refusal to give an inch of ground saved his company from possible encirclement and destruction and enabled it to hold the woods which had been the enemy’s objective”.

Let Murphy’s Medal of Honor Citation describe what happened next: “Second Lieutenant Audie L. Murphy, 01692509, 15th Infantry, Army of the United States, on 26 January 1945, near Holtzwihr, France, commanded Company B, which was attacked by six tanks and waves of infantry. Lieutenant Murphy ordered his men to withdraw to a prepared position in a woods while he remained forward at his command post and continued to give fire directions to the artillery by telephone. Behind him to his right one of our tank destroyers received a direct hit and began to burn. Its crew withdrew to the woods. Lieutenant Murphy continued to direct artillery fire which killed large numbers of the advancing enemy infantry. With the enemy tanks abreast of his position, Lieutenant Murphy climbed on the burning tank destroyer which was in danger of blowing up any instant and employed its .50 caliber machine gun against the enemy. He was alone and exposed to the German fire from three sides, but his deadly fire killed dozens of Germans and caused their infantry attack to waver. The enemy tanks, losing infantry support, began to fall back. For an hour the Germans tried every available weapon to eliminate Lieutenant Murphy, but he continued to hold his position and wiped out a squad which was trying to creep up unnoticed on his right flank. Germans reached as close as 10 yards only to be mowed down by his fire. He received a leg wound but ignored it and continued the single-handed fight until his ammunition was exhausted. He then made his way to his company, refused medical attention, and organized the company in a counterattack which forced the Germans to withdraw. His directing of artillery fire wiped out many of the enemy; he personally killed or wounded about 50. Lieutenant Murphy’s indomitable courage and his refusal to give an inch of ground saved his company from possible encirclement and destruction and enabled it to hold the woods which had been the enemy’s objective”. Hollywood and, until his death in a plane crash in 1971, his post-war life was never free of it.

Hollywood and, until his death in a plane crash in 1971, his post-war life was never free of it.

In all the annals of warfare, there may be nothing more ironic, than the time a naval force was defeated by men mounted on horseback.

In all the annals of warfare, there may be nothing more ironic, than the time a naval force was defeated by men mounted on horseback.

At least one source will tell you that this event never occurred, or at least it’s an embellished version, as retold by the hussars themselves. I guess you can take your pick. A number of 19th century authors have portrayed the episode as unvarnished history, as have a number of paintings and sketches.

At least one source will tell you that this event never occurred, or at least it’s an embellished version, as retold by the hussars themselves. I guess you can take your pick. A number of 19th century authors have portrayed the episode as unvarnished history, as have a number of paintings and sketches.

Lieutenant Trung to be particularly hard core, a tough guy in a world of tough guys. A US Marine Corps Lieutenant of Korean ancestry, dressed in the uniform of the Blue Dragon Marines, and paid a visit to Lt. Trung’s cell. Not a word or gesture passed between the two, the mere presence of a Blue Dragon was enough to get this guy talking. Korean fighters are no joke.

Lieutenant Trung to be particularly hard core, a tough guy in a world of tough guys. A US Marine Corps Lieutenant of Korean ancestry, dressed in the uniform of the Blue Dragon Marines, and paid a visit to Lt. Trung’s cell. Not a word or gesture passed between the two, the mere presence of a Blue Dragon was enough to get this guy talking. Korean fighters are no joke. brained political calculations of DPRK leadership. Somehow it made sense to these guys, that to assassinate the South Korean President and hurl his head out of the official residence, would start a popular uprising leading to the re-unification of the Korean peninsula under DPRK government.

brained political calculations of DPRK leadership. Somehow it made sense to these guys, that to assassinate the South Korean President and hurl his head out of the official residence, would start a popular uprising leading to the re-unification of the Korean peninsula under DPRK government. Korean military and police personnel were killed along with two dozen civilians, and 66 wounded. Four Americans were killed in efforts to prevent Unit 124 members from re-crossing the DMZ.

Korean military and police personnel were killed along with two dozen civilians, and 66 wounded. Four Americans were killed in efforts to prevent Unit 124 members from re-crossing the DMZ. and other hardened prisoners, possibly due to the suicidal nature of their mission. The “training” they were subjected to on Silmido Island, off the coast of Inchon, was beyond brutal. Seven of them would not survive it.

and other hardened prisoners, possibly due to the suicidal nature of their mission. The “training” they were subjected to on Silmido Island, off the coast of Inchon, was beyond brutal. Seven of them would not survive it.

“Zero Hour” program, part of a Japanese psychological warfare campaign designed to lower the morale of US Armed Forces. The name “Tokyo Rose” was in common use by this time, applied to as many as 12 different women broadcasting Japanese propaganda in English. Toguri DJ’d a program with American music punctuated by Japanese slanted news articles for 1¼ hours, six days a week, starting at 6:00pm Tokyo time. Altogether, her on-air speaking time averaged 15-20 minutes for most broadcasts.

“Zero Hour” program, part of a Japanese psychological warfare campaign designed to lower the morale of US Armed Forces. The name “Tokyo Rose” was in common use by this time, applied to as many as 12 different women broadcasting Japanese propaganda in English. Toguri DJ’d a program with American music punctuated by Japanese slanted news articles for 1¼ hours, six days a week, starting at 6:00pm Tokyo time. Altogether, her on-air speaking time averaged 15-20 minutes for most broadcasts. After the war, a number of reporters were looking for the mythical “Tokyo Rose”, and two of them found Iva Aquino. They were Henry Brundidge and Clark Lee, and they offered her a significant sum for her story. The money never materialized, but she signed a contract giving the two rights to her story, and identifying herself as Tokyo Rose.

After the war, a number of reporters were looking for the mythical “Tokyo Rose”, and two of them found Iva Aquino. They were Henry Brundidge and Clark Lee, and they offered her a significant sum for her story. The money never materialized, but she signed a contract giving the two rights to her story, and identifying herself as Tokyo Rose.

Reformatory for Women at Alderson, West Virginia in 1956, having served six years and two months of her sentence.

Reformatory for Women at Alderson, West Virginia in 1956, having served six years and two months of her sentence.

Later in the same conflict, an Iraqi Hughes 500 helicopter was taken out by bombs dropped from an American Air Force F-15E bomber. At least one Iraqi PC-7 Turboprop pilot got spooked, bailing out of a perfectly good aircraft before a shot was fired in his direction.

Later in the same conflict, an Iraqi Hughes 500 helicopter was taken out by bombs dropped from an American Air Force F-15E bomber. At least one Iraqi PC-7 Turboprop pilot got spooked, bailing out of a perfectly good aircraft before a shot was fired in his direction.

As the army began the famous crossing of the Delaware that Christmas night, the

As the army began the famous crossing of the Delaware that Christmas night, the many of them lacked boots, the soaked and freezing rags wrapped around their feet not enough to keep them from leaving bloody footprints in the snow.

many of them lacked boots, the soaked and freezing rags wrapped around their feet not enough to keep them from leaving bloody footprints in the snow. The Patriot force arrived at Trenton at 8am December 26, completely surprising the Hessian garrison. There is a story about the Hessians being drunk or hungover after Christmas celebrations, but the story is almost certainly untrue. Unaware of Washington’s march on Trenton, 50 Americans had attacked a Hessian outpost earlier that morning. While Washington worried that his surprise was blown, Colonel Rall apparently believed that this was the attack he’d been warned about. He expected no further action that day.

The Patriot force arrived at Trenton at 8am December 26, completely surprising the Hessian garrison. There is a story about the Hessians being drunk or hungover after Christmas celebrations, but the story is almost certainly untrue. Unaware of Washington’s march on Trenton, 50 Americans had attacked a Hessian outpost earlier that morning. While Washington worried that his surprise was blown, Colonel Rall apparently believed that this was the attack he’d been warned about. He expected no further action that day. under Generals Cornwallis and Grant, proving on January 3rd at a place called Princeton, that they could defeat a regular British army in the field.

under Generals Cornwallis and Grant, proving on January 3rd at a place called Princeton, that they could defeat a regular British army in the field.

You must be logged in to post a comment.