Yonaguni Island, the westernmost inhabited island of the Japanese archipelago, lies about 60 miles across the straits of Taiwan. The place is a popular dive destination, due to (or possibly despite) a large population of hammerhead sharks.

In 1987, divers discovered an enormous stone formation, with angles and straight lines seemingly too perfect to have been formed by nature. If this “Yonaguni Monument” is in fact a prehistoric stone megalith, it would have to have been carved 8,000 to 10,000 years ago when the area was last dry, radically changing current ideas about prehistoric construction.

A map of the world is dotted with such ancient stone megaliths, from Easter Island in the South Pacific to the Carnac Stones of France, and the stone spheres of Costa Rica. Among all of them, there is no story more mysterious, or more tragic, than the Plain of Jars.

Deep in the heart of the Indochinese peninsula of mainland Southeast Asia lies the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, (LPDR), informally known as Muang Lao or just Laos. To the north of the country lies the Xiangkhouang Plateau, known in French as Plateau du Tran-Ninh, situated between the Luang Prabang mountain range separating Laos from Thailand, and the Annamite Range along the Vietnamese border.

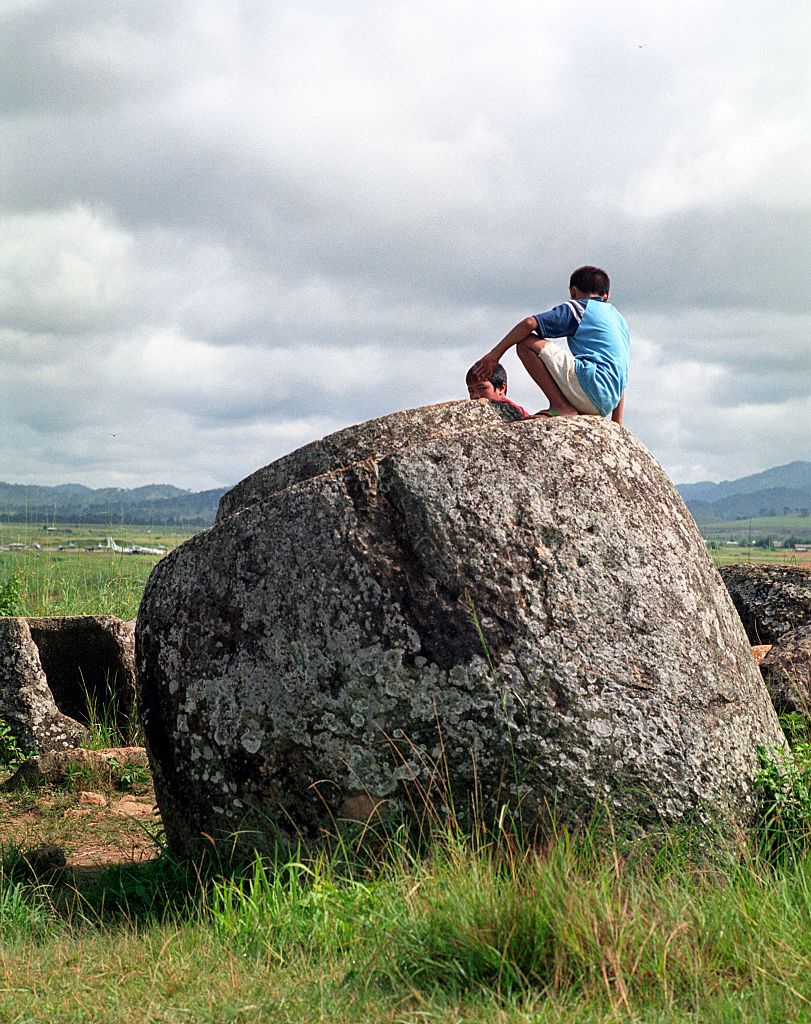

Fifteen-hundred to twenty-five hundred years ago, a now-vanished race of bronze and iron age craftsmen carved stone jars out of solid rock, ranging in size from 3 to 9-feet or more. There are thousands of these jars, located at 90 separate sites containing just a single to four hundred apiece.

Most of these jars have carved rims but few have lids, leading researchers to speculate that lids were formed from organic material such as wood or leather.

Lao legend has it that the jars belonged to a race of giants, who chiseled them out of sandstone, granite, conglomerate, limestone and breccia to hold “lau hai”, or rice beer. More likely they were part of some ancient funerary rite, where the dead and the about-to-die were inserted along with personal goods and ornaments such as beads made of glass and carnelian, cowrie shells and bronze bracelets and bells. There the deceased were “distilled” in a sitting position, later to be removed and cremated with remains then going through a secondary burial.

These “Plain of Jars” sites might be some of the oldest burial grounds in the world, but be careful if you go there. It’s the most dangerous archaeological site on earth.

With the final French stand at Dien Bien Phu a short five months in the future, France signed the Franco–Lao Treaty of Amity and Association in 1953, establishing Laos as an independent member of the French Union. The Laotian Civil War broke out that same year between the Communist Pathet Lao and the Royal Lao Government, becoming a “proxy war” where both sides received heavy support from the global Cold War superpowers.

Concerned about a “domino effect” in Southeast Asia, US direct foreign aid to Laos began as early as 1950. Five years later the country suffered a catastrophic failure of the rice crop. The CIA-operated Civil Air Transport (CAT) flew over 200 missions to 25 drop zones, delivering 1,000 tons of emergency food. By 1959, the CIA “air proprietary” was operating fixed and rotary wing aircraft in Laos, under the renamed “Air America”.

The Geneva Convention of 1954 partitioned Vietnam at the 17th parallel, and guaranteed Laotian neutrality. North Vietnamese communists had no intention of withdrawing from the country or abandoning Laotian communist allies, any more than they were going to abandon the drive for military reunification, with the south.

Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Arleigh Burke warned the Joint Chiefs of Staff, “If we lose Laos, we will probably lose Thailand and the rest of Southeast Asia. We will have demonstrated to the world that we cannot or will not stand when challenged”.

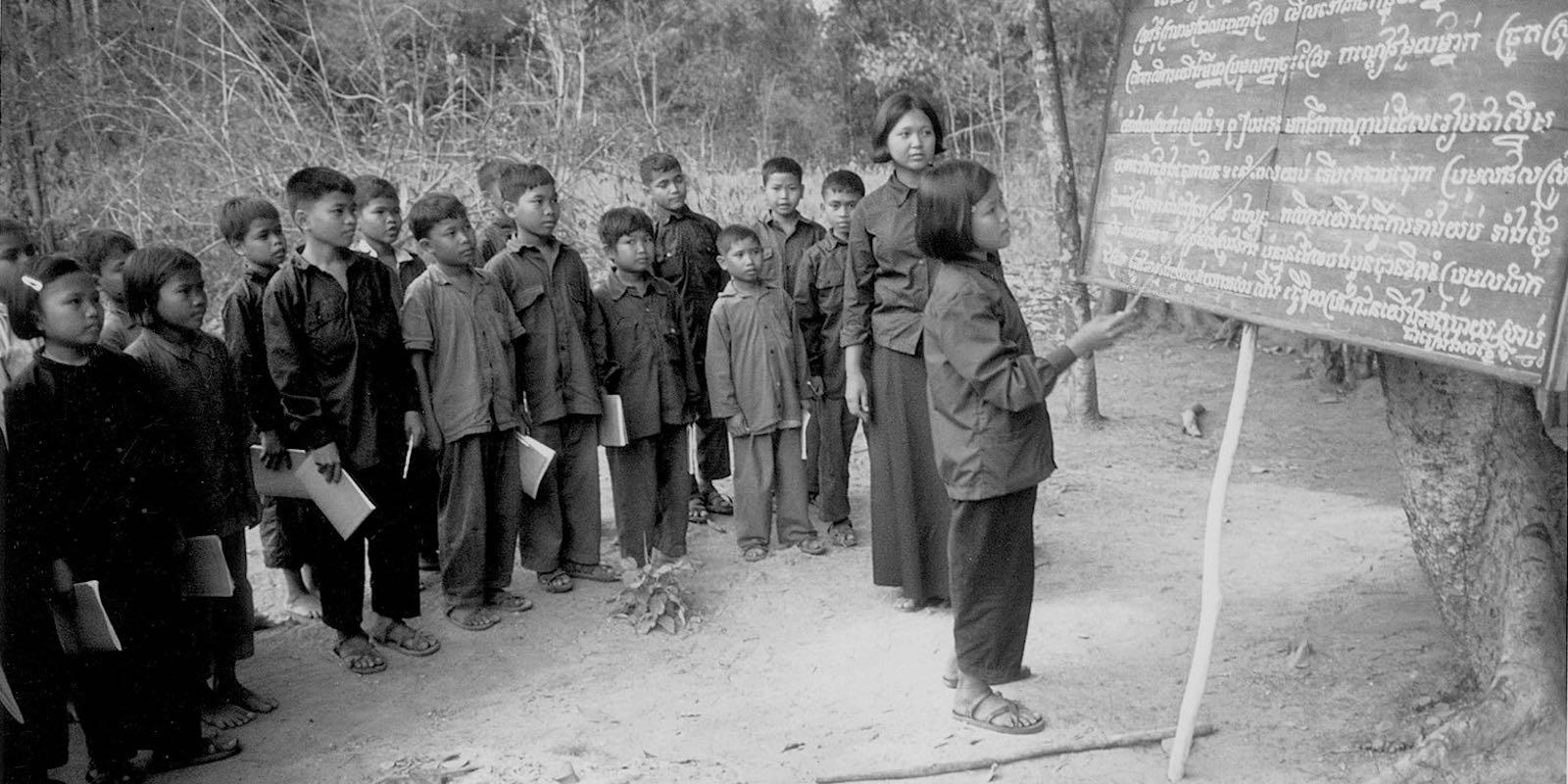

As the American war ramped up in Vietnam, the CIA fought a “Secret War” in Laos, in support of a growing force of Laotian highland tribesmen called the Hmong, fighting the leftist Pathet Lao and North Vietnamese communists.

Primitive footpaths had existed for centuries along the Laotian border with Vietnam, facilitating trade and travel. In 1959, Hanoi established the 559th Transportation Group under Colonel Võ Bẩm, improving these trails into a logistical system connecting the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in the north, to the Republic of Vietnam in the south. At first just a means of infiltrating manpower, this “Hồ Chí Minh trail” through Laos and Cambodia soon morphed into a major logistical supply line.

In the last months of his life, President John F. Kennedy authorized the CIA to increase the size of the Hmong army. As many as 20,000 Highlanders took arms against far larger communist forces, acting as guerrillas, blowing up NVA supply depots, ambushing trucks and mining roads. The response was genocidal. As many as 18,000 – 20,000 Hmong tribesman were hunted down and murdered by Vietnamese and Laotian communists.

Air America helicopter pilot Dick Casterlin wrote to his parents that November, “The war is going great guns now. Don’t be misled [by reports] that I am only carrying rice on my missions as wars aren’t won by rice.”

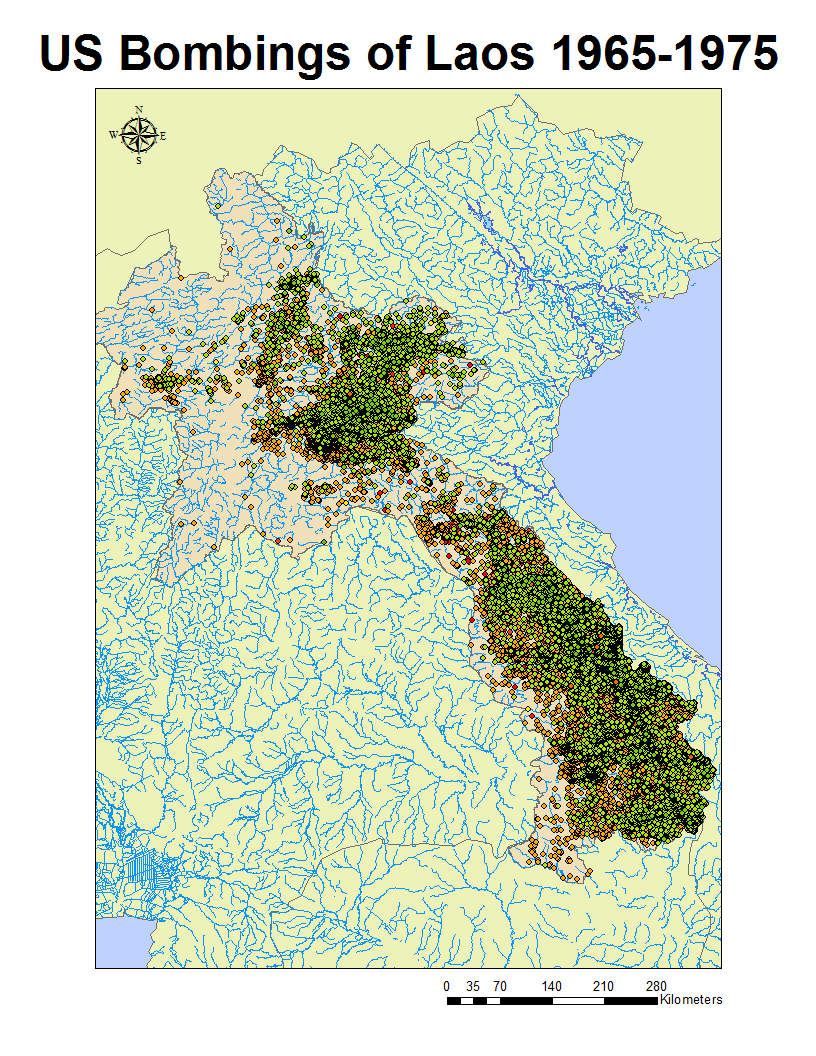

The proxy war in Laos reached a new high in 1964, in what the agency itself calls “the largest paramilitary operations ever undertaken by the CIA.” In the period 1964-’73, the US flew some 580,344 bombing missions over the Hồ Chí Minh trail and Plain of Jars, dropping an estimated 262 million bomb. Two million tons, equivalent to a B-52 bomber full of bombs every eight minutes, 24 hours a day, for nine years. More bombs than US Army Air Forces dropped in all of WW2, making Laos the most heavily bombed country, per capita, in history.

Most were “cluster munitions”, bomb shells designed to open in flight, showering the earth with hundreds of “bomblets” intended to kill people and destroy vehicles. It’s been estimated that 30% of these munitions failed to explode, 80 million of them, (the locals call them “bombies”), set to go off with the weight of a foot, or a wheel, or the touch of a garden hoe.

Since the end of the war, some 20,000 civilians have been killed or maimed by unexploded ordnance, called “UXO”. Four in ten of those, are children.

Removal of such vast quantities of UXO is an effort requiring considerable time and money and no small amount of personal risk. The American Mennonite community became pioneers in the effort in the years following the war, one of the few international Non-Governmental Organizations (NGO’s) trusted by the habitually suspicious communist leadership of the LPDR.

On February 18, 1977, Murray Hiebert, now senior associate of the Southeast Asia Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C. summed up the situation in a letter to the Mennonite Central Committee, US: “…a formerly prosperous people still stunned and demoralized by the destruction of their villages, the annihilation of their livestock, the cratering of their fields, and the realization that every stroke of their hoes is potentially fatal.

Years later, Unesco archaeologists worked to unlock the secrets of the Plain of Jars, working side by side with ordnance removal teams.

In 1996, United States Special Forces began a “train the trainer” program in UXO removal, at the invitation of the LPDR government. Even so, Western Embassy officials in the Laotian capitol of Vientiane believed that, at the current pace, total removal will take “several hundred years”.

In 2004, bomb metal fetched 7.5 Pence Sterling, per kilogram. That’s eleven cents, for just over two pounds. Unexploded ordnance brought in 50 Pence per kilogram in the communist state, inviting young and old alike to attempt the dismantling of an endless supply of BLU-26 cluster bomblets. For seventy cents apiece.

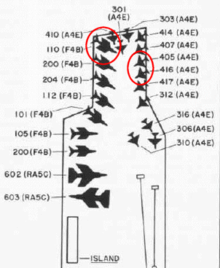

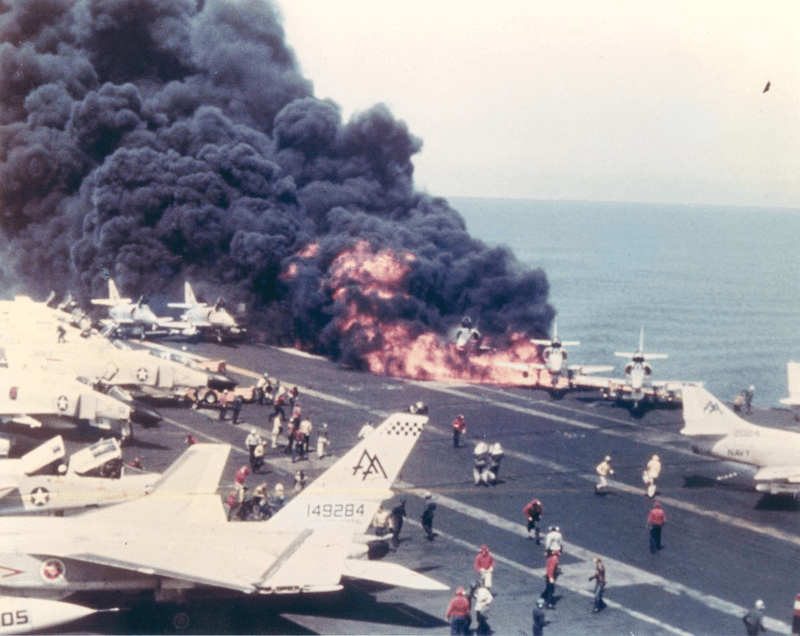

These older bombs were way past their “sell-by” date, having spent the better part of the last ten years in the heat and humidity of Subic Bay depots. Ordnance officers wanted nothing to do with the Fat Boys, with their rusting shells leaking paraffin, and rotted packaging. Some had production date stamps as early as 1953.

These older bombs were way past their “sell-by” date, having spent the better part of the last ten years in the heat and humidity of Subic Bay depots. Ordnance officers wanted nothing to do with the Fat Boys, with their rusting shells leaking paraffin, and rotted packaging. Some had production date stamps as early as 1953. In addition to the bombs, ground attack aircraft were armed with 5″ “Zuni” unguided rockets, carried four at a time in under-wing rocket packs. Known for electrical malfunctions and accidental firing, standard Naval procedure required electrical pigtails to be connected, at the catapult.

In addition to the bombs, ground attack aircraft were armed with 5″ “Zuni” unguided rockets, carried four at a time in under-wing rocket packs. Known for electrical malfunctions and accidental firing, standard Naval procedure required electrical pigtails to be connected, at the catapult.

Gary Childs of Paxton Massachusetts, my uncle, was among the hundreds of sailors and marines who fought to bring the fire under control. Gary was below decks when the fire broke out, leaving moments before his quarters were engulfed in flames. Only by that slimmest of margins did any number of sailors aboard the USS Forrestal, escape being #135.

Gary Childs of Paxton Massachusetts, my uncle, was among the hundreds of sailors and marines who fought to bring the fire under control. Gary was below decks when the fire broke out, leaving moments before his quarters were engulfed in flames. Only by that slimmest of margins did any number of sailors aboard the USS Forrestal, escape being #135.

France re-occupied the region following the Japanese defeat which ended World War 2, but soon faced the same opposition from the army of Ho Chi Minh and Vo Nguyen Giap.

France re-occupied the region following the Japanese defeat which ended World War 2, but soon faced the same opposition from the army of Ho Chi Minh and Vo Nguyen Giap. US policy makers feared a “domino” effect, and with good cause. The 15 core nations of the Soviet bloc were soon followed by Eastern Europe, as Poland, Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary and Czechoslovakia fell each in their turn, into the Soviet sphere of influence. Germany was partitioned into Communist and free-enterprise spheres after WWII, followed by China, North Korea and on across Southeast Asia.

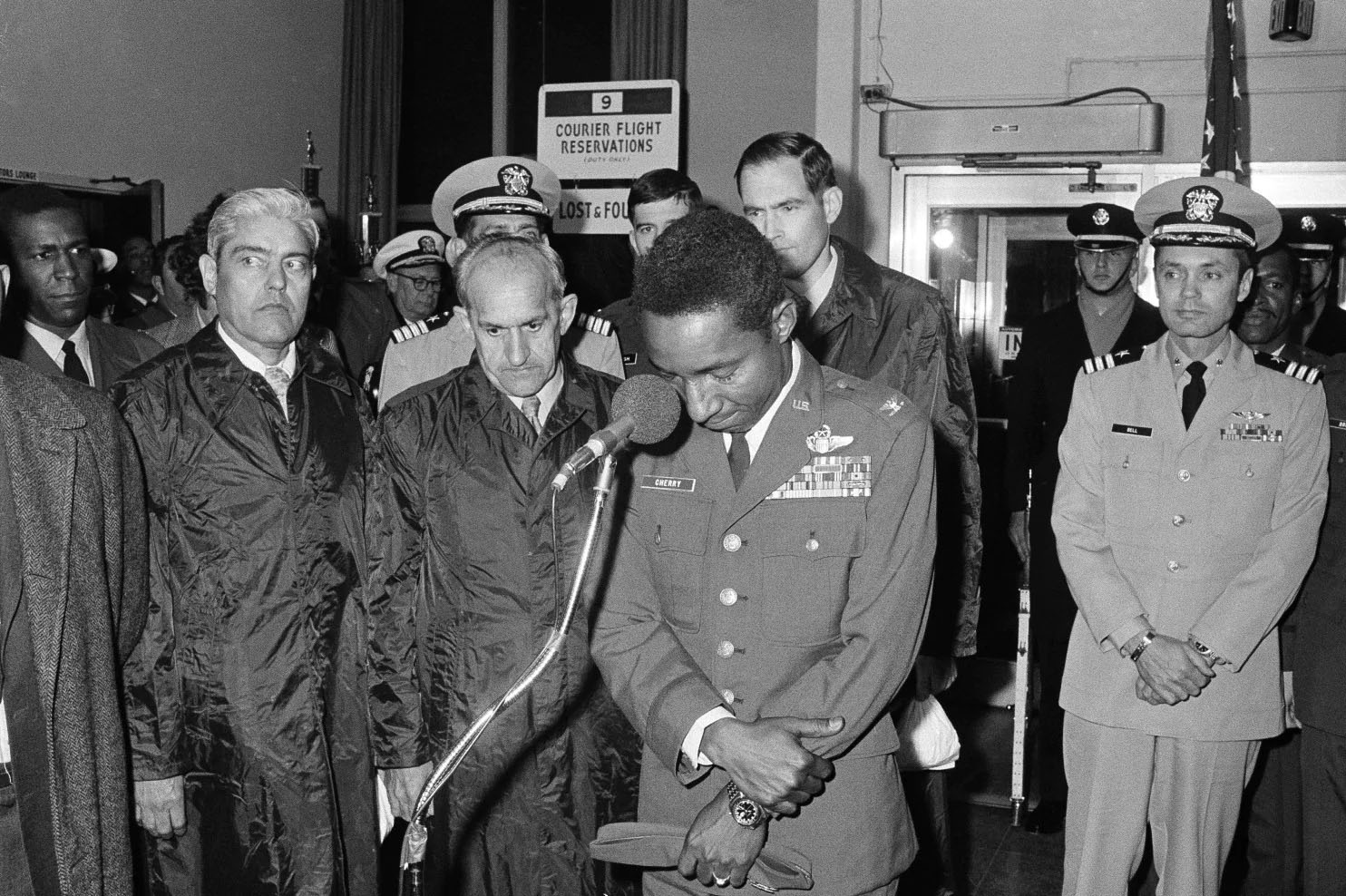

US policy makers feared a “domino” effect, and with good cause. The 15 core nations of the Soviet bloc were soon followed by Eastern Europe, as Poland, Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary and Czechoslovakia fell each in their turn, into the Soviet sphere of influence. Germany was partitioned into Communist and free-enterprise spheres after WWII, followed by China, North Korea and on across Southeast Asia. The war in Vietnam pitted as many as 1.8 million allied forces from South Vietnam, the United States, Thailand, Australia, the Philippines, Spain, South Korea and New Zealand, against about a half million from North Vietnam, China, the Soviet Union and North Korea. Begun on November 1, 1955, the conflict lasted 19 years, 5 months and a day. On March 29, 1973, two months after signing the Paris Peace accords, the last US combat troops left South Vietnam as Hanoi freed the remaining POWs held in North Vietnam.

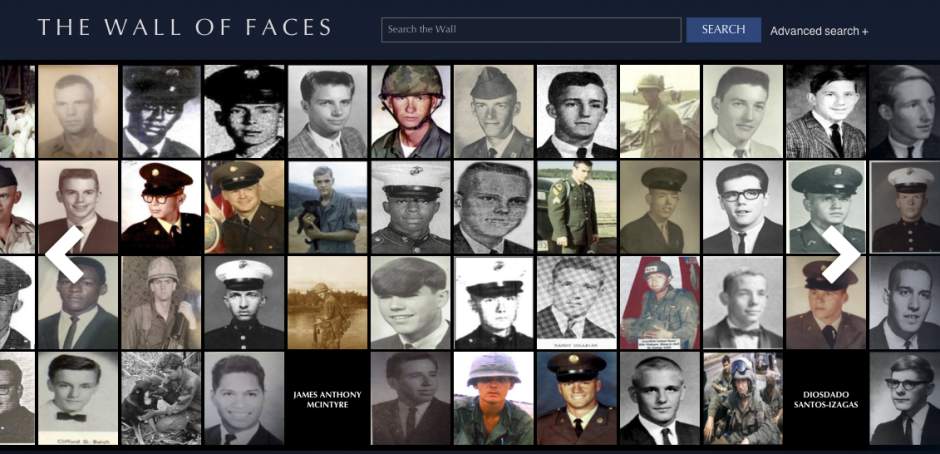

The war in Vietnam pitted as many as 1.8 million allied forces from South Vietnam, the United States, Thailand, Australia, the Philippines, Spain, South Korea and New Zealand, against about a half million from North Vietnam, China, the Soviet Union and North Korea. Begun on November 1, 1955, the conflict lasted 19 years, 5 months and a day. On March 29, 1973, two months after signing the Paris Peace accords, the last US combat troops left South Vietnam as Hanoi freed the remaining POWs held in North Vietnam. Even then it wasn’t over. Communist forces violated cease-fire agreements before they were even signed. Some 7,000 US civilian Department of Defense employees stayed behind to aid South Vietnam in conducting an ongoing and ultimately futile war against communist North Vietnam.

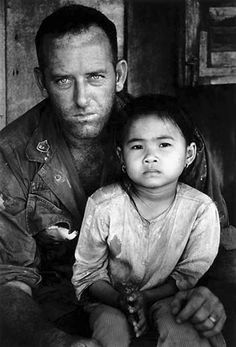

Even then it wasn’t over. Communist forces violated cease-fire agreements before they were even signed. Some 7,000 US civilian Department of Defense employees stayed behind to aid South Vietnam in conducting an ongoing and ultimately futile war against communist North Vietnam. Imagine feeling so desperate, so fearful of the alien ideology invading your country, that you convert all your worldly possessions and those of your family into a single diamond, and bite down on that stone so hard it embeds in your shattered teeth. Forced to flee for your life and those of your young ones, you take to the open ocean in a small boat. All in the faint and desperate hope, of getting out of that place.

Imagine feeling so desperate, so fearful of the alien ideology invading your country, that you convert all your worldly possessions and those of your family into a single diamond, and bite down on that stone so hard it embeds in your shattered teeth. Forced to flee for your life and those of your young ones, you take to the open ocean in a small boat. All in the faint and desperate hope, of getting out of that place. The humanitarian disaster that was the Indochina refugee crisis was particularly acute between 1979 – ’80, but reverberations continued into the 21st century.

The humanitarian disaster that was the Indochina refugee crisis was particularly acute between 1979 – ’80, but reverberations continued into the 21st century.

In the end, US public opinion would not sustain what too many saw as an endless war in Vietnam. We feel the political repercussions, to this day. I was ten at the time of the Tet Offensive in 1968. Even then I remember the searing sense of disgrace and humiliation, at the behavior of some of my fellow Americans.

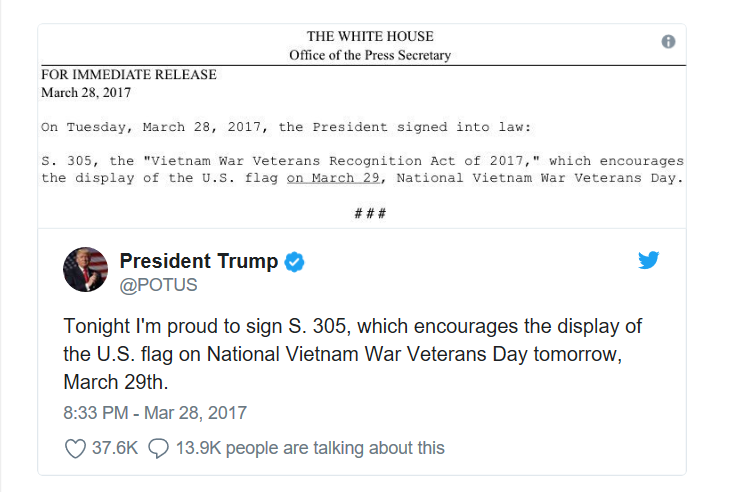

In the end, US public opinion would not sustain what too many saw as an endless war in Vietnam. We feel the political repercussions, to this day. I was ten at the time of the Tet Offensive in 1968. Even then I remember the searing sense of disgrace and humiliation, at the behavior of some of my fellow Americans. In 2012, President Barack Obama declared a one-time occasion proclaiming March 29 National Vietnam War Veterans Day and calling on “all Americans to observe this day with appropriate programs, ceremonies, and activities.”

In 2012, President Barack Obama declared a one-time occasion proclaiming March 29 National Vietnam War Veterans Day and calling on “all Americans to observe this day with appropriate programs, ceremonies, and activities.”

By 1967, the Johnson administration was coming under increasing criticism, for what many of the American public saw as an endless and pointless stalemate in Vietnam.

By 1967, the Johnson administration was coming under increasing criticism, for what many of the American public saw as an endless and pointless stalemate in Vietnam. One of the largest military operations of the war launched on January 30, 1968, coinciding with the Tết holiday, the Vietnamese New Year. In the first wave of attacks, North Vietnamese troops and Viet Cong Guerillas struck over 100 cities and towns including Saigon, the South Vietnamese capitol.

One of the largest military operations of the war launched on January 30, 1968, coinciding with the Tết holiday, the Vietnamese New Year. In the first wave of attacks, North Vietnamese troops and Viet Cong Guerillas struck over 100 cities and towns including Saigon, the South Vietnamese capitol. While the Tết offensive was a military defeat for the forces of North Vietnam, the political effects on the American public, were profound. Support for the war effort plummeted, leading to demonstrations. Jeers could be heard in the streets. “Hey! Hey! LBJ! How many kids did you kill today?”

While the Tết offensive was a military defeat for the forces of North Vietnam, the political effects on the American public, were profound. Support for the war effort plummeted, leading to demonstrations. Jeers could be heard in the streets. “Hey! Hey! LBJ! How many kids did you kill today?” Lyndon Johnson’s Presidency, was finished. The following month, Johnson appeared before the nation in a televised address, saying “I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your president.”

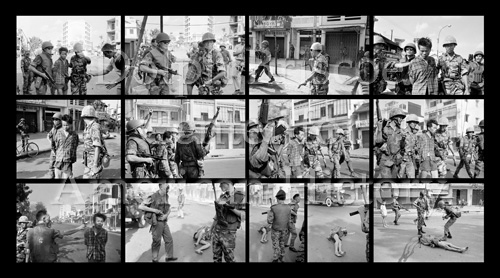

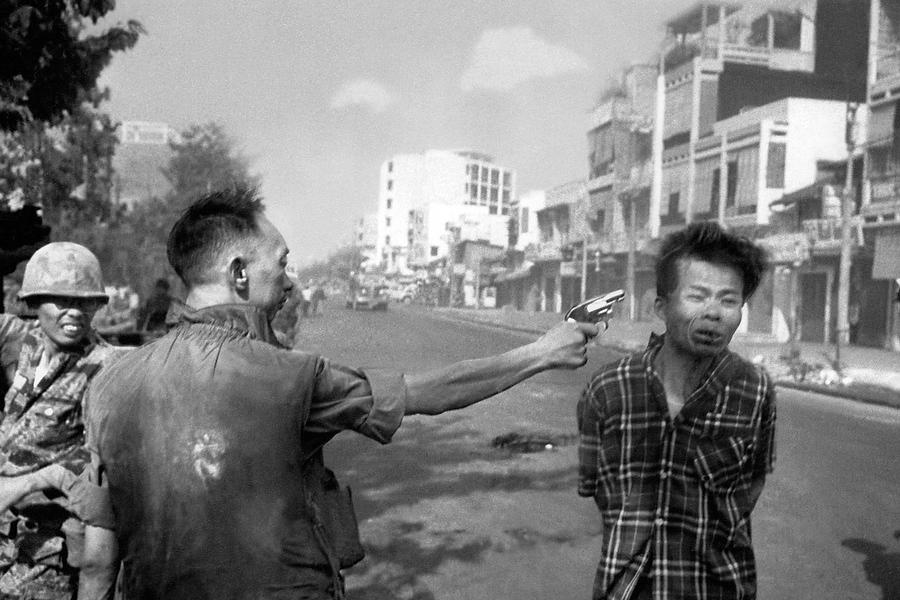

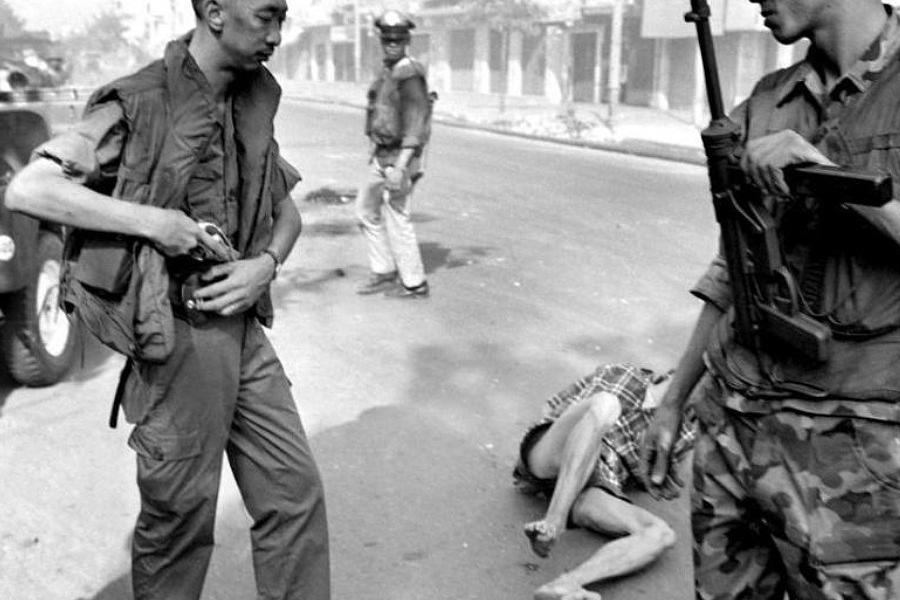

Lyndon Johnson’s Presidency, was finished. The following month, Johnson appeared before the nation in a televised address, saying “I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your president.” AP photographer Eddie Adams was out on the street with NBC News television cameraman Võ Sửu, looking for something interesting. The pair saw a group of South Vietnamese soldiers dragging what appeared to be an ordinary man into the road, and filmed the event.

AP photographer Eddie Adams was out on the street with NBC News television cameraman Võ Sửu, looking for something interesting. The pair saw a group of South Vietnamese soldiers dragging what appeared to be an ordinary man into the road, and filmed the event.

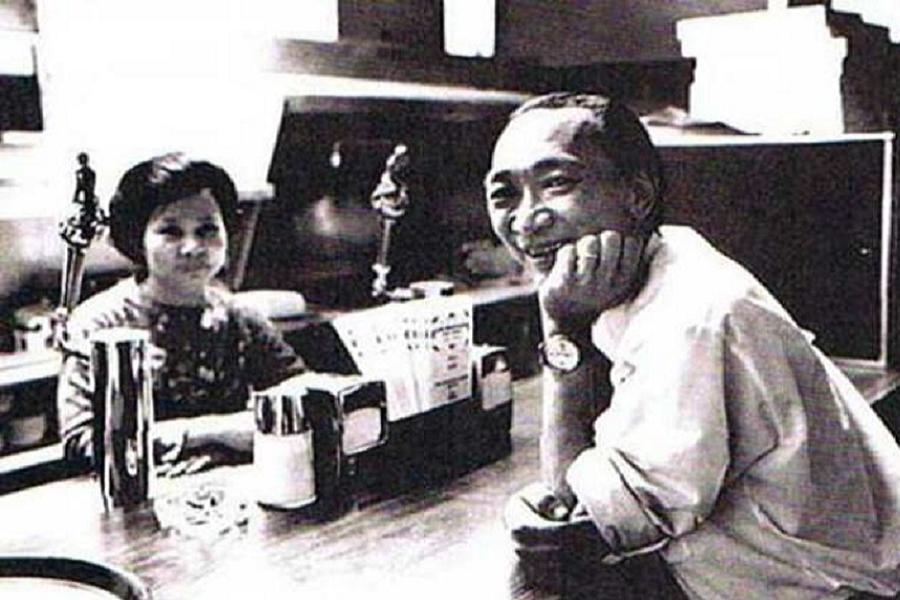

The couple was forced to close the restaurant in 1991. Nguyễn Ngọc Loan died of cancer, seven years later.

The couple was forced to close the restaurant in 1991. Nguyễn Ngọc Loan died of cancer, seven years later.

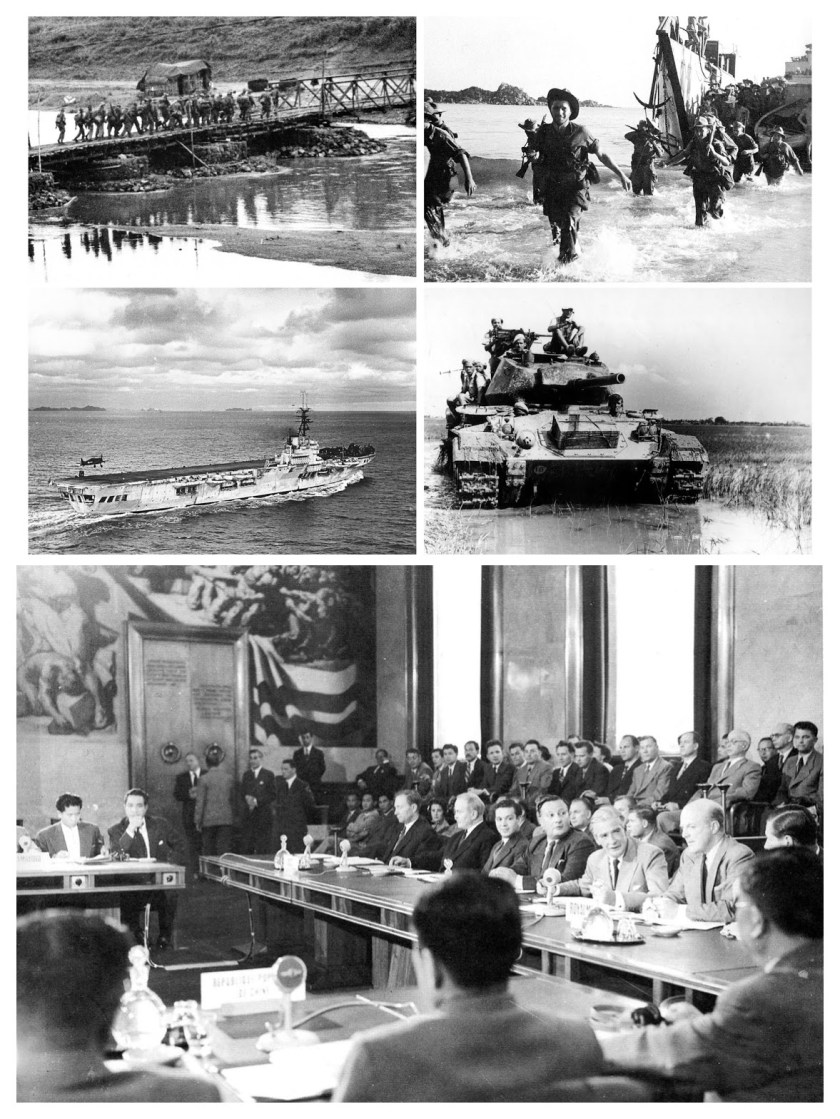

What historians call the First Indochina War, many contemporaries called “la sale guerre”, or “dirty war”. The government forbade the use of metropolitan recruits, fearing that that would make the war more unpopular than it already was. Instead, French professional soldiers and units of the French Foreign Legion were augmented with colonial troops, including Moroccan, Algerian, Tunisian, Laotian, Cambodian, and Vietnamese ethnic minorities.

What historians call the First Indochina War, many contemporaries called “la sale guerre”, or “dirty war”. The government forbade the use of metropolitan recruits, fearing that that would make the war more unpopular than it already was. Instead, French professional soldiers and units of the French Foreign Legion were augmented with colonial troops, including Moroccan, Algerian, Tunisian, Laotian, Cambodian, and Vietnamese ethnic minorities. The war went poorly for the Colonial power. By 1952 the French were looking for a way out. Premier René Mayer appointed Henri Navarre to take command of French Union Forces in May of that year with a single order. Navarre was to create military conditions which would lead to an “honorable political solution”.

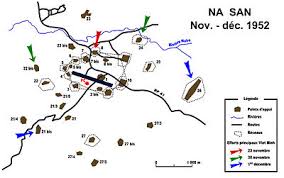

The war went poorly for the Colonial power. By 1952 the French were looking for a way out. Premier René Mayer appointed Henri Navarre to take command of French Union Forces in May of that year with a single order. Navarre was to create military conditions which would lead to an “honorable political solution”. In June, Major General René Cogny proposed a “mooring point” at Dien Bien Phu, creating a lightly defended point from which to launch raids. Navarre wanted to replicate the Na San strategy and ordered that Dien Bien Phu be taken and converted to a heavily fortified base.

In June, Major General René Cogny proposed a “mooring point” at Dien Bien Phu, creating a lightly defended point from which to launch raids. Navarre wanted to replicate the Na San strategy and ordered that Dien Bien Phu be taken and converted to a heavily fortified base. The French staff made their battle plan, based on the assumption that it was impossible for the Viet Minh to place enough artillery on the surrounding high ground, due to the rugged terrain. The communists didn’t possess enough artillery to do serious damage anyway, or so they thought.

The French staff made their battle plan, based on the assumption that it was impossible for the Viet Minh to place enough artillery on the surrounding high ground, due to the rugged terrain. The communists didn’t possess enough artillery to do serious damage anyway, or so they thought.

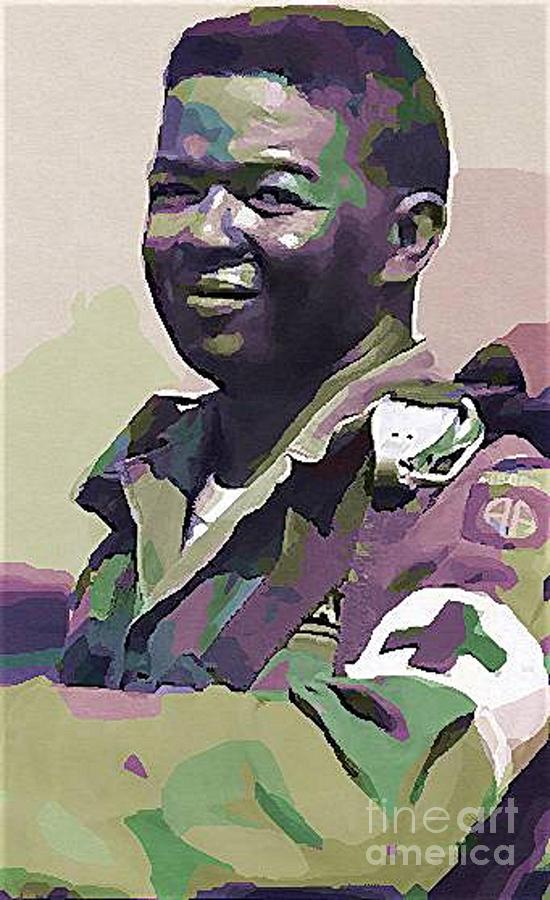

On this day in 1965, the 173rd Airborne Infantry Brigade was halfway through a one-year term of service, in Vietnam. “Operation Hump”, so named in recognition of that mid-point, was a search and destroy mission inserted by helicopter on November 5.

On this day in 1965, the 173rd Airborne Infantry Brigade was halfway through a one-year term of service, in Vietnam. “Operation Hump”, so named in recognition of that mid-point, was a search and destroy mission inserted by helicopter on November 5. There was little contact through the evening of the 7th, when B and C Companies of the 1/503rd took up a night defensive position in the triple canopied jungle near Hill 65.

There was little contact through the evening of the 7th, when B and C Companies of the 1/503rd took up a night defensive position in the triple canopied jungle near Hill 65. Outnumbered in some places six to one, it was a desperate fight for survival as parts of B and C companies were isolated in fighting that was shoulder to shoulder, hand to hand.

Outnumbered in some places six to one, it was a desperate fight for survival as parts of B and C companies were isolated in fighting that was shoulder to shoulder, hand to hand. “For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of life above and beyond the call of duty. Specialist 5 Joel demonstrated indomitable courage, determination, and professional skill when a numerically superior and well-concealed Viet Cong element launched a vicious attack which wounded or killed nearly every man in the lead squad of the company. After treating the men wounded by the initial burst of gunfire, he bravely moved forward to assist others who were wounded while proceeding to their objective. While moving from man to man, he was struck in the right leg by machine gun fire. Although painfully wounded his desire to aid his fellow soldiers transcended all personal feeling. He bandaged his own wound and self-administered morphine to deaden the pain enabling him to continue his dangerous undertaking. Through this period of time, he constantly shouted words of encouragement to all around him. Then, completely ignoring the warnings of others, and his pain, he continued his search for wounded, exposing himself to hostile fire; and, as bullets dug up the dirt around him, he held plasma bottles high while kneeling completely engrossed in his life saving mission. Then, after being struck a second time and with a bullet lodged in his thigh, he dragged himself over the battlefield and succeeded in treating 13 more men before his medical supplies ran out. Displaying resourcefulness, he saved the life of one man by placing a plastic bag over a severe chest wound to congeal the blood. As 1 of the platoons pursued the Viet Cong, an insurgent force in concealed positions opened fire on the platoon and wounded many more soldiers. With a new stock of medical supplies,

“For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of life above and beyond the call of duty. Specialist 5 Joel demonstrated indomitable courage, determination, and professional skill when a numerically superior and well-concealed Viet Cong element launched a vicious attack which wounded or killed nearly every man in the lead squad of the company. After treating the men wounded by the initial burst of gunfire, he bravely moved forward to assist others who were wounded while proceeding to their objective. While moving from man to man, he was struck in the right leg by machine gun fire. Although painfully wounded his desire to aid his fellow soldiers transcended all personal feeling. He bandaged his own wound and self-administered morphine to deaden the pain enabling him to continue his dangerous undertaking. Through this period of time, he constantly shouted words of encouragement to all around him. Then, completely ignoring the warnings of others, and his pain, he continued his search for wounded, exposing himself to hostile fire; and, as bullets dug up the dirt around him, he held plasma bottles high while kneeling completely engrossed in his life saving mission. Then, after being struck a second time and with a bullet lodged in his thigh, he dragged himself over the battlefield and succeeded in treating 13 more men before his medical supplies ran out. Displaying resourcefulness, he saved the life of one man by placing a plastic bag over a severe chest wound to congeal the blood. As 1 of the platoons pursued the Viet Cong, an insurgent force in concealed positions opened fire on the platoon and wounded many more soldiers. With a new stock of medical supplies,  Specialist 5 Joel again shouted words of encouragement as he crawled through an intense hail of gunfire to the wounded men. After the 24 hour battle subsided and the Viet Cong dead numbered 410, snipers continued to harass the company. Throughout the long battle, Specialist 5 Joel never lost sight of his mission as a medical aid man and continued to comfort and treat the wounded until his own evacuation was ordered. His meticulous attention to duty saved a large number of lives and his unselfish, daring example under most adverse conditions was an inspiration to all. Specialist 5. Joel’s profound concern for his fellow soldiers, at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty are in the highest traditions of the U.S. Army and reflect great credit upon himself and the Armed Forces of his country“.

Specialist 5 Joel again shouted words of encouragement as he crawled through an intense hail of gunfire to the wounded men. After the 24 hour battle subsided and the Viet Cong dead numbered 410, snipers continued to harass the company. Throughout the long battle, Specialist 5 Joel never lost sight of his mission as a medical aid man and continued to comfort and treat the wounded until his own evacuation was ordered. His meticulous attention to duty saved a large number of lives and his unselfish, daring example under most adverse conditions was an inspiration to all. Specialist 5. Joel’s profound concern for his fellow soldiers, at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty are in the highest traditions of the U.S. Army and reflect great credit upon himself and the Armed Forces of his country“.

What historians call the First Indochina War, many contemporaries called “la sale guerre”, or “dirty war”. The government forbade the use of metropolitan recruits, fearing that that would make the war more unpopular than it already was. Instead, French professional soldiers and units of the French Foreign Legion were augmented with colonial troops, including Moroccan, Algerian, Tunisian, Laotian, Cambodian, and Vietnamese ethnic minorities.

What historians call the First Indochina War, many contemporaries called “la sale guerre”, or “dirty war”. The government forbade the use of metropolitan recruits, fearing that that would make the war more unpopular than it already was. Instead, French professional soldiers and units of the French Foreign Legion were augmented with colonial troops, including Moroccan, Algerian, Tunisian, Laotian, Cambodian, and Vietnamese ethnic minorities.

The French staff formulated their battle plan, based on the assumption that it was impossible for the Viet Minh to place enough artillery on the surrounding high ground, due to the rugged terrain. Communist forces didn’t possess enough artillery to do serious damage anyway. Or so they thought.

The French staff formulated their battle plan, based on the assumption that it was impossible for the Viet Minh to place enough artillery on the surrounding high ground, due to the rugged terrain. Communist forces didn’t possess enough artillery to do serious damage anyway. Or so they thought. “Beatrice” was the first fire base to fall, then “Gabrielle” and “Anne-Marie”. Viet Minh controlled 90% of the airfield by the 22nd of April, making even parachute drops next to impossible. On May 7, Vo ordered an all-out assault of 25,000 troops against the 3,000 remaining in garrison. By nightfall it was over. The last words from the last radio man were “The enemy has overrun us. We are blowing up everything. Vive la France!”

“Beatrice” was the first fire base to fall, then “Gabrielle” and “Anne-Marie”. Viet Minh controlled 90% of the airfield by the 22nd of April, making even parachute drops next to impossible. On May 7, Vo ordered an all-out assault of 25,000 troops against the 3,000 remaining in garrison. By nightfall it was over. The last words from the last radio man were “The enemy has overrun us. We are blowing up everything. Vive la France!”

American support for the south increased as the French withdrew theirs. By the late 1950s, the United States were sending technical and financial aid in expectation of social and land reform. By 1960, the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (NLF, or “Viet Cong”) had taken to murdering Diem supported village leaders. President John Fitzgerald Kennedy responded by sending 1,364 American advisers into South Vietnam, in 1961.

American support for the south increased as the French withdrew theirs. By the late 1950s, the United States were sending technical and financial aid in expectation of social and land reform. By 1960, the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (NLF, or “Viet Cong”) had taken to murdering Diem supported village leaders. President John Fitzgerald Kennedy responded by sending 1,364 American advisers into South Vietnam, in 1961.

You must be logged in to post a comment.