It’s one of the oldest diseases in recorded history, the first written reference coming down to us, from 600BC. Ancient Greeks, Chinese, Indians and Middle Eastern sources wrote about the condition as did the Roman naturalist Pliny the elder, in the first century.

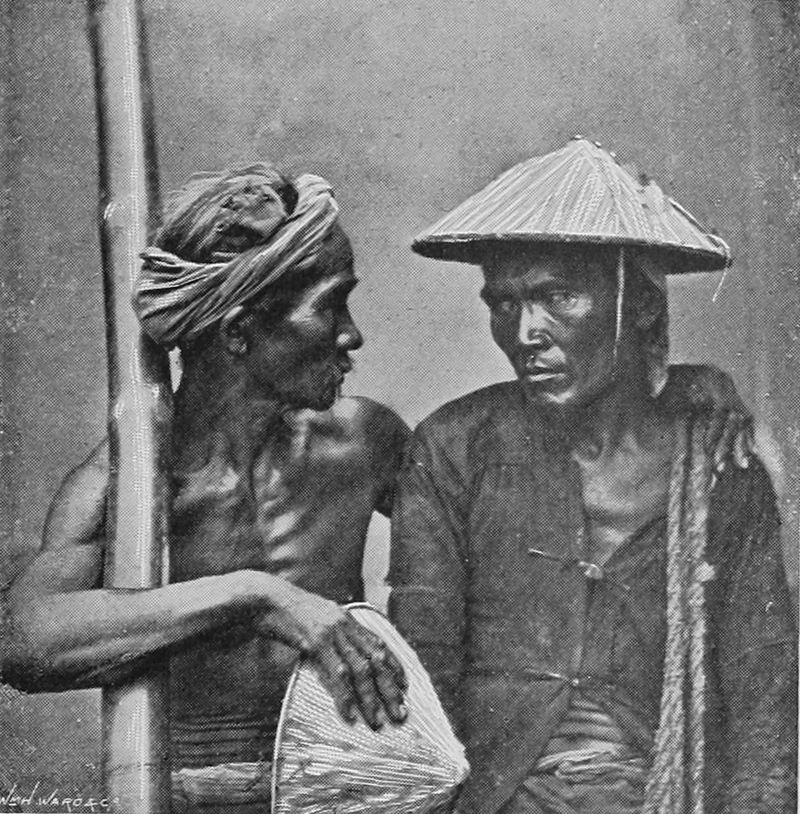

Leprosy is a chronic disease caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium leprae. Left untreated the condition produces skin ulcers, damage to peripheral nerves & upper respiratory tract, and muscular weakness. Everyday injuries go unnoticed due to numbness and lead to infection. Advanced cases result in severe disfigurement, crippling and/or the physical loss of hands, feet & facial features, and, finally, blindness.

The World Health Organization (WHO) reports a death rate among leprosy sufferers four times that of the general population.

First discovered by Norwegian physician G.H. Armauer Hansen in 1873, M. leprae is the first bacterium identified as the causative agent of disease, in humans. Today, Leprosy is curable with multidrug therapy (MDT). The world saw 208,619 new cases in 2018, 185 of which occurred, in the United States.

The horrors of the condition and resulting social stigmas, are plain for anyone to see. Today, sufferers fear loss of jobs, separation of familial and other connections and social isolation. Though not as widespread as commonly believed, victims of “Hansen’s disease” were historically sent off to quarantine in asylums and “leper colonies” from which few, ever returned.

In the 19th century, Mycobacterium leprae came to the Hawaiian islands.

According to research, long-distance explorers first came to the Hawaiian islands around the year 300. For the next 500 years, settlers arrived from French Polynesia, Tahiti, Tuamotus and the Samoan Islands. Other research indicates a shorter timeframe, settlement occurring between 1219 and 1266. Be that as it may the Hawaiian islands were first unified in 1810 to become the Kingdom of Hawai’i, under King Kamehameha the Great. Captain James Cook made the first known European contact in 1778 followed by waves of others both European, and American.

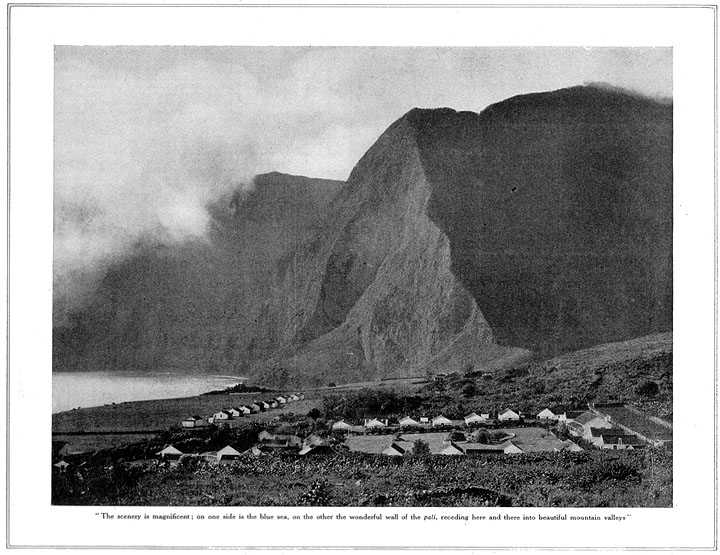

According to archaeological evidence, indigenous peoples occupied the Kalaupapa peninsula on the Hawaiian island of Moloka’i, for more than 900 years. Before first contact with Europeans their numbers are estimated, between 1,000 and 2,700, . Following the arrival of Captain Cook and others, Eurasian diseases decimated native populations. By 1853 only were 140 natives were left on the Kalaupapa peninsula.

Leprosy first arrived on the Hawaiian islands around 1830, believed to be carried by Chinese laborers. The disease was incurable at that time, the first effective treatment didn’t come around, until the1940s.

By 1865, sugar planters were concerned about the labor supply. The Kingdom passed a measure to remove the Kānaka Maoli, Native Hawaiian inhabitants occupying the peninsula, in preparation for a leper colony.

The first such isolation settlement was established at Kalawao on the windward side of the peninsula and then on Kalaupapa, itself.

Even after a year of family disruption brought about by government response to Covid-19 the catastrophe of such a policy, is hard to process. In native Hawaiian tradition, Aloha ʻĀina means not only “Love of the Land” but a deep sense of connection, to all living things. For the descendants of those forcibly removed from the ʻĀina as well as those “lost” to Kalaupapa the wounds remain open, to this day.

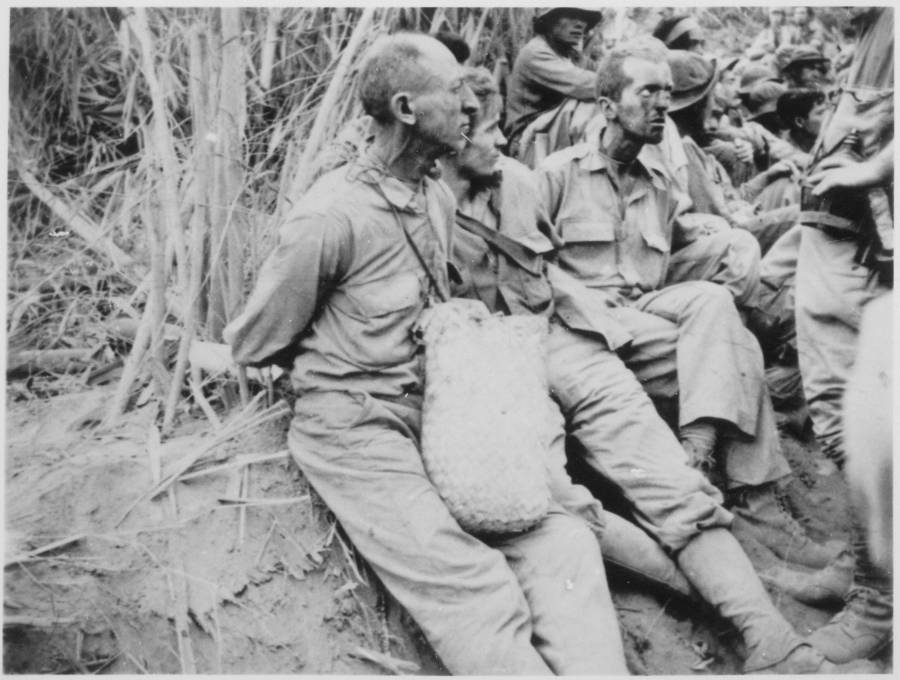

By 1890, 1,100 ‘lepers’ lived in this remote, inhospitable place, prisoners of their own deteriorating bodies and a greater culture who loathed, and feared them.

Over the years some 8,500 unfortunates would come to live in this place, the last one, in 1969.

Rudolph Wilhelm Meyer set out from his native Germany in search of the California gold rush. He made it as far as Molokaʻi. By 1866, Meyer was a father and husband to Kalama Waha, settled on the steep cliffs above Kalaupapa. As the peninsula became a leper colony, Meyer became supply agent to the colony and liaison to those few healthy individuals, willing to work there.

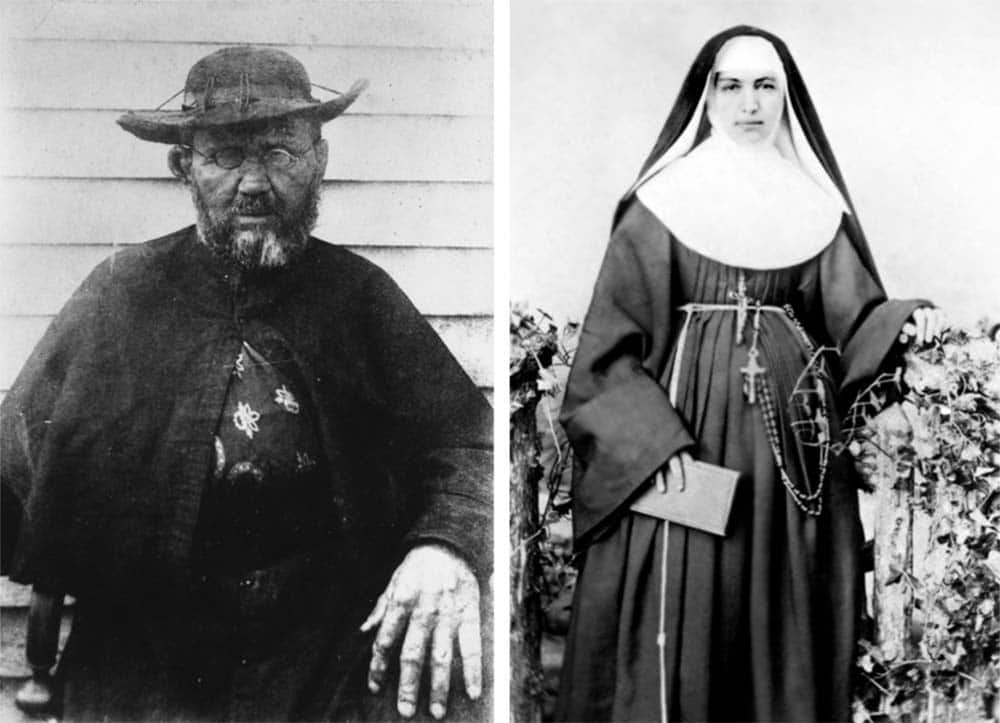

Mostly, those were Belgian missionary priests from the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary, the first of whom was Father Damien, who served there from 1873 until his death, in 1889.

Father Damien arrived at the isolated settlement at Kalaupapa on May 10, 1873. At that time there were 600 lepers. He spoke to the assembled unfortunates as “one who will be a father to you, and who loves you so much that he does not hesitate to become one of you; to live and die with you.”

After the Fr. Damien’s death of leprosy, commentators complained of contemporary accounts diminishing the work of native Hawaiians, some of whom served prominent roles on the island. While such are accounts are likely true enough there is no diminishing what the man did there.

For 16 years, father Damien lived and worked among the lepers of Molokaʻi. He ate with them, from the same bowls. He smoked with them, from the same pipe.

While the government had no desire to make this place a penal colony, outside support was slim to none. And this was no isolated population of yeoman farmers, these people were sickened and made weak by this most dreadful of medical conditions, many barely able to care for themselves.

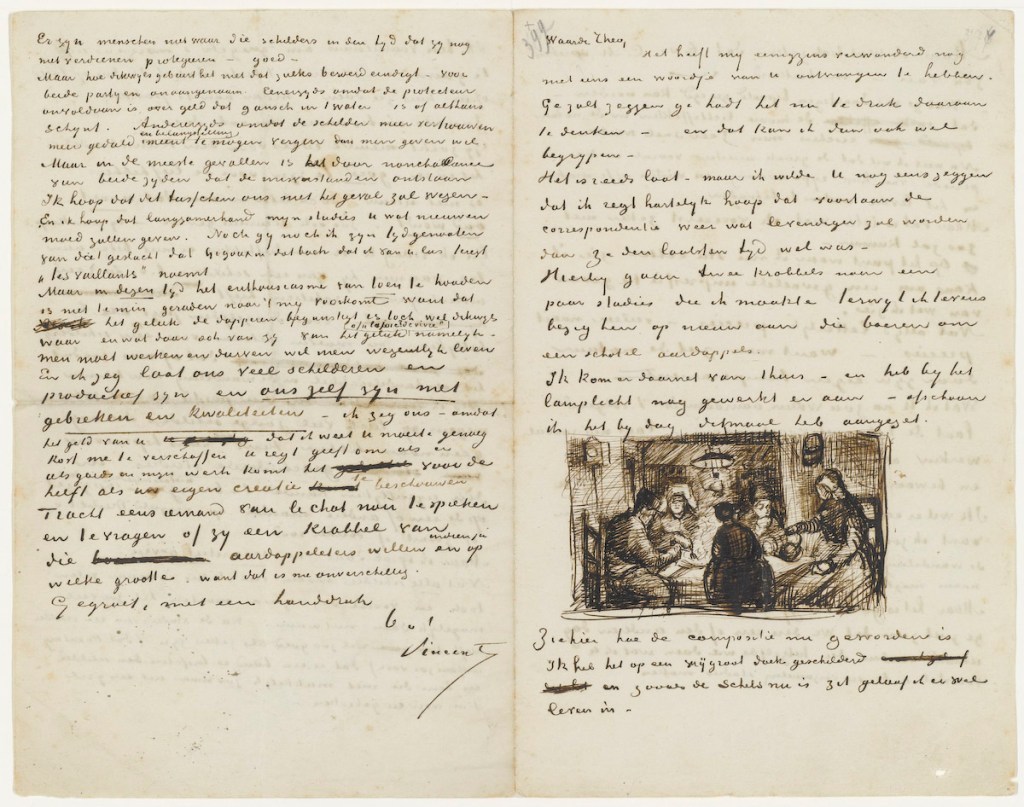

Damien was not only a priest and teacher, he pitched in painting houses, organizing farms and building roads, hospitals and churches. He dressed the wounds of the stricken, built their coffins, dug graves and lived with the lepers, as equals. Six months after his arrival at Kalawao he wrote to his brother, Pamphile, in Europe: “…I make myself a leper with the lepers to gain all to Jesus Christ.”

One day, it happened. In December 1884, he accidentally put his foot in scalding water. It was so hot that his skin blistered and peeled but he didn’t feel a thing. Father Damien was now himself, a leper.

Despite the illness destroying his body, Damien worked even harder in the last years of his life. He completed several building projects and improved orphanages, all while aiding his fellow lepers in their treatments and medical baths and spreading the Catholic faith. King David Kalākaua bestowed on the priest the honor of “Knight Commander of the Royal Order of Kalākaua.” When Crown Princess Lydia Liliʻuokalani arrived to present the medal she was said to be too distraught and heartbroken at the sight of those poor people, to even speak.

Princess Liliʻuokalani spoke of her experience bringing the plight of Father Damien and his flock, to the eyes of the world. European and American protestants sent money to help with the work. The Church of England sent food, medicine and supplies. It is believed that Fr. Damien never wore his medal but he went to his grave, with it by his side.

Japanese leprologist Masanao Goto arrived to treat the lepers of Molokaʻi with medical baths, moderate exercise and friction applied to parts, benumbed by disease. Goto’s treatments were popular with his patients but, in the end, there was little hope. Four volunteers arrived in the end to aid the ailing missionary including sister Marianne Cope, a woman who would one day join Father Damien, in Roman Catholic sainthood.

By February 1889, the end was near. With his foot in bandages and an arm in a sling, his other leg dragging uselessly behind, Damien went to his death bed on March 23. Father Damien died of leprosy at 8:00am on April 15, 1889. He was 49. The entire colony turned out the following day as the Belgian missionary was laid to rest beside the same pandamus tree under which he had slept those sixteen years earlier, on his first night in Molokaʻi.

In John 15:13, the King James Bible teaches that “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.” Today, I wonder how many know the name of Father Damien, of Molokaʻi . Or the faith which would bring a person to willingly submit to the literal rot, of such a hideous condition.

Let Mahatma Ghandi, himself no stranger to the horrors of leprosy, have the last word on that subject: “The political and journalistic world can boast of very few heroes who compare with Father Damien of Molokai. The Catholic Church, on the contrary, counts by the thousands those who, after the example of Fr. Damien, have devoted themselves to the victims of leprosy. It is worthwhile to look for the sources of such heroism“.

Feature image, top of page: Kalaupapa leper colony in 1905

You must be logged in to post a comment.