The scandal started with Arnold “Chick” Gandil, the first baseman with ties to Chicago gangsters. Gandil convinced Joseph “Sport” Sullivan, a friend and professional gambler, that he could throw the upcoming World Series against the Cincinnati Reds. A New York gangster named Arnold Rothstein supplied the money through his right-hand man, the former featherweight boxing champion Abe Attell, and the “fix was in”.

Pitchers Eddie Cicotte and Claude “Lefty” Williams, along with outfielder Oscar “Hap” Felsch, and shortstop Charles “Swede” Risberg were all principally involved with fixing the series. Third baseman George “Buck” Weaver was at a meeting where the fix was discussed, but decided not to participate. Weaver handed in some of his best statistics of the year during the Series.

Pitchers Eddie Cicotte and Claude “Lefty” Williams, along with outfielder Oscar “Hap” Felsch, and shortstop Charles “Swede” Risberg were all principally involved with fixing the series. Third baseman George “Buck” Weaver was at a meeting where the fix was discussed, but decided not to participate. Weaver handed in some of his best statistics of the year during the Series.

Star outfielder “Shoeless” Joe Jackson may have been a participant, though his involvement is disputed. It seems that other players may have used his name in order to give themselves credibility. Utility infielder Fred McMullin was not involved in the planning, but he threatened to report the others unless they cut him in on the payoff.

The more “straight arrow” players on the club knew nothing about the fix. Second baseman Eddie Collins, catcher Ray Schalk, and pitcher Red Faber had nothing to do with it, though the conspiracy got an unexpected boost when Faber came down with the flu.

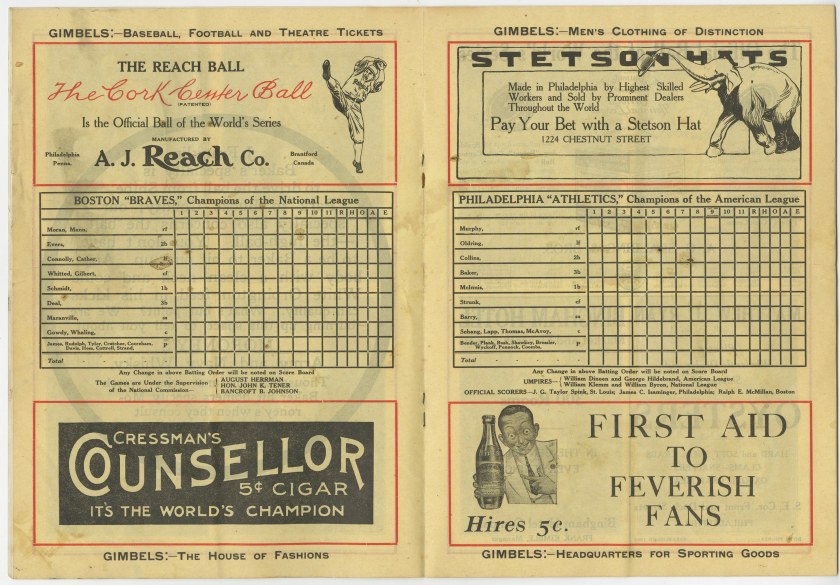

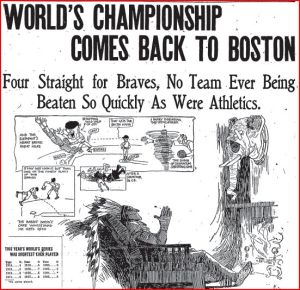

Rumors were flying when the series started on October 2. So much money was on Cincinnati that the odds were flat. Gamblers complained that nothing was left on the table. Williams lost his three games in the best-out-of nine series, which I believe stands as a World Series record to this day. Cicotte became angry, thinking that gamblers were trying to renege, and he bore down, the White Sox winning game 7.

Rumors were flying when the series started on October 2. So much money was on Cincinnati that the odds were flat. Gamblers complained that nothing was left on the table. Williams lost his three games in the best-out-of nine series, which I believe stands as a World Series record to this day. Cicotte became angry, thinking that gamblers were trying to renege, and he bore down, the White Sox winning game 7.

Williams was back on the mound in game 8. By this time he wanted out, but gangsters threatened to hurt him and his family if he didn’t lose the game. The White Sox lost Game 8 on October 9, ending the series 3 to 5.

Rumors of the thrown series followed the White Sox through the 1920 season and a grand jury was convened that September. Two players, Eddie Cicotte and Shoeless Joe Jackson, testified on September 28, 1920, both confessing to participating in the scheme. Despite a virtual tie for first place at the time, club owner Chuck Comiskey pulled the seven players then in the majors (Gandil was back in the minors at the time). The damage to the sport’s reputation prior to the 1921 season was profound.

Franchise owners appointed a man with the best “baseball name” in history to help straighten out the mess. He was Major League Baseball’s first Commissioner, federal judge Kennesaw Mountain Landis.

Key evidence went missing from the Cook County courthouse before the trial, including Cicotte’s and Jackson’s signed confessions. Both recanted and, in the end, all players were acquitted. The missing confessions reappeared several years later in the possession of Comiskey’s lawyer. It’s funny how that works.

Key evidence went missing from the Cook County courthouse before the trial, including Cicotte’s and Jackson’s signed confessions. Both recanted and, in the end, all players were acquitted. The missing confessions reappeared several years later in the possession of Comiskey’s lawyer. It’s funny how that works.

According to legend, a young boy approached Shoeless Joe Jackson one day as he came out of the courthouse. “Say it ain’t so, Joe”. There was no response.

The Commissioner was unforgiving, irrespective of the verdict. The day after the acquittal, Landis issued a statement: “Regardless of the verdict of juries, no player who throws a ball game, no player who undertakes or promises to throw a ball game, no player who sits in confidence with a bunch of crooked ballplayers and gamblers, where the ways and means of throwing a game are discussed and does not promptly tell his club about it, will ever play professional baseball”.

Jackson, Cicotte, Gandil, Felsch, Weaver, Williams, Risberg, and McMullin are long dead now, but every one remains Banned from Baseball.

Ironically, the 1919 scandal would lead to a White Sox crash in the 1921 season, beginning the “Curse of the Black Sox”. It was a World Series championship drought that lasted 88 years, ending only in 2005, with a sweep of the Houston Astros. Exactly one year after the Boston Red Sox ended their own 86-year drought, the “Curse of the Bambino”.

Ironically, the 1919 scandal would lead to a White Sox crash in the 1921 season, beginning the “Curse of the Black Sox”. It was a World Series championship drought that lasted 88 years, ending only in 2005, with a sweep of the Houston Astros. Exactly one year after the Boston Red Sox ended their own 86-year drought, the “Curse of the Bambino”.

The Philadelphia Bulletin newspaper published a poem back on opening day for the 1919 series. They would probably have taken it back, if only they could.

“Still, it really doesn’t matter, After all, who wins the flag.

Good clean sport is what we’re after, And we aim to make our brag.

To each near or distant nation, Whereon shines the sporting sun.

That of all our games gymnastic, Base ball is the cleanest one!”

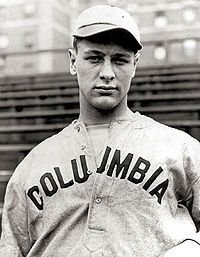

Gehrig was pitching for Columbia University against Williams College on April 18, 1923, the day that Babe Ruth hit the first home run out of the brand new Yankee Stadium. Though Columbia would lose the game, Gehrig struck out seventeen batters to set a team record. The loss didn’t matter to Paul Krichell, the Yankee scout who had been following Gehrig. Krichell didn’t care about the arm either, as much as he did that powerful left-handed bat. He had seen Gehrig hit some of the longest home runs ever seen on several Eastern campuses, including a 450′ home run at Columbia’s South Field that cleared the stands, landing at 116th Street and Broadway.

Gehrig was pitching for Columbia University against Williams College on April 18, 1923, the day that Babe Ruth hit the first home run out of the brand new Yankee Stadium. Though Columbia would lose the game, Gehrig struck out seventeen batters to set a team record. The loss didn’t matter to Paul Krichell, the Yankee scout who had been following Gehrig. Krichell didn’t care about the arm either, as much as he did that powerful left-handed bat. He had seen Gehrig hit some of the longest home runs ever seen on several Eastern campuses, including a 450′ home run at Columbia’s South Field that cleared the stands, landing at 116th Street and Broadway.

Gehrig left the team in June, arriving at the Mayo Clinic on the 13th. The diagnosis of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) was confirmed six days later, on June 19. It was his 36th birthday. It was a cruel prognosis: rapidly increasing paralysis, difficulty in swallowing and speaking, and a life expectancy of fewer than three years.

Gehrig left the team in June, arriving at the Mayo Clinic on the 13th. The diagnosis of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) was confirmed six days later, on June 19. It was his 36th birthday. It was a cruel prognosis: rapidly increasing paralysis, difficulty in swallowing and speaking, and a life expectancy of fewer than three years.

Lambeau worked for the Indian Packing Company in those days, making $250 a month as a shipping clerk. The two went to Lambeau’s employer and got a commitment for $500 for team uniforms, provided that the team use the company’s name. Today, “Green Bay Packers” is the oldest team name still in use in the NFL.

Lambeau worked for the Indian Packing Company in those days, making $250 a month as a shipping clerk. The two went to Lambeau’s employer and got a commitment for $500 for team uniforms, provided that the team use the company’s name. Today, “Green Bay Packers” is the oldest team name still in use in the NFL.

No other club in professional football history has won three consecutive championships. The Packers did it twice: 1929–1931, and 1965–1967.

No other club in professional football history has won three consecutive championships. The Packers did it twice: 1929–1931, and 1965–1967.

Gehrig was pitching for Columbia University against Williams College on April 18, 1923, the day that Babe Ruth hit the first home run out of the brand new Yankee Stadium. Though Columbia would lose the game, Gehrig struck out seventeen batters to set a team record.

Gehrig was pitching for Columbia University against Williams College on April 18, 1923, the day that Babe Ruth hit the first home run out of the brand new Yankee Stadium. Though Columbia would lose the game, Gehrig struck out seventeen batters to set a team record.

Gehrig appeared at Yankee Stadium on “Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day”, July 4, 1939. He was awarded trophies and other tokens of affection by the New York sports media, fellow players and groundskeepers. He would place each one on the ground, already too weak to hold them. Addressing his fans, Gehrig described himself as “The Luckiest Man on the Face of the Earth”.

Gehrig appeared at Yankee Stadium on “Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day”, July 4, 1939. He was awarded trophies and other tokens of affection by the New York sports media, fellow players and groundskeepers. He would place each one on the ground, already too weak to hold them. Addressing his fans, Gehrig described himself as “The Luckiest Man on the Face of the Earth”.

Rick Monday had served a tour in the Marine Corp Reserve, in fulfillment of his ROTC obligation after leaving Arizona State. “If you’re going to burn the flag”, he said, “don’t do it around me. I’ve been to too many veterans’ hospitals and seen too many broken bodies of guys who tried to protect it.”

Rick Monday had served a tour in the Marine Corp Reserve, in fulfillment of his ROTC obligation after leaving Arizona State. “If you’re going to burn the flag”, he said, “don’t do it around me. I’ve been to too many veterans’ hospitals and seen too many broken bodies of guys who tried to protect it.”

losing its National League team to Washington, DC. Only moments before, Padres’ President Buzzie Bavasi had to leave Kroc’s side to investigate concession area water in the clubhouse, when a leak was “promoted” to a flood.

losing its National League team to Washington, DC. Only moments before, Padres’ President Buzzie Bavasi had to leave Kroc’s side to investigate concession area water in the clubhouse, when a leak was “promoted” to a flood. Buzzie Bavasi did the most to defuse the situation. Taking a cue from Rader’s comments, Bavasi designated the next game in the Houston series “Short Order Cook’s Night”. Any Padres fan who came wearing a chef’s hat, would be admitted into the game for free. Rader, the Astro’s team captain, took the lineup card to home plate wearing an apron with a chef’s hat, slipping the card off a skillet with a spatula and handing it over to the home plate umpire, like a pancake.

Buzzie Bavasi did the most to defuse the situation. Taking a cue from Rader’s comments, Bavasi designated the next game in the Houston series “Short Order Cook’s Night”. Any Padres fan who came wearing a chef’s hat, would be admitted into the game for free. Rader, the Astro’s team captain, took the lineup card to home plate wearing an apron with a chef’s hat, slipping the card off a skillet with a spatula and handing it over to the home plate umpire, like a pancake.

For those of us who rooted for the New England Patriots during the losing years, the 1986 Super Bowl XX was the worst moment ever. We all had our “Berry da Bears” shirts on. Life was good when New England took the earliest lead in Super Bowl history, with a field goal at 1:19.

For those of us who rooted for the New England Patriots during the losing years, the 1986 Super Bowl XX was the worst moment ever. We all had our “Berry da Bears” shirts on. Life was good when New England took the earliest lead in Super Bowl history, with a field goal at 1:19.

You must be logged in to post a comment.