In January 1848, carpenter and sawmill operator James W. Marshall discovered gold in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountains, in California. Prospectors flocked to the Golden State from across the United States, and abroad. The California Gold Rush had begun.

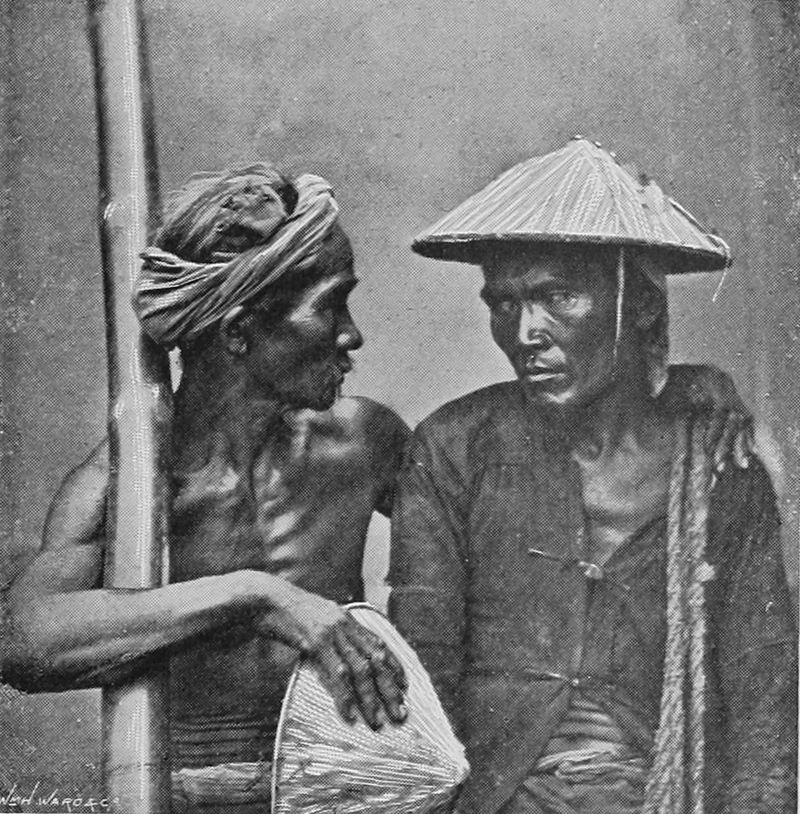

While not exactly welcoming, prospectors tolerated Chinese immigrants in the early period. Surface gold was plentiful in those days. Some even found the chopsticks and the broad conical hats of the Chinese mining camps, amusing. As competition increased, resentment began to build. Meanwhile in southern China, crop failures and rumors of the Golden Mountain, the Gam Saan, brought with it a tide of Chinese immigration. San Francisco saw a tenfold increase in 1852, alone. Now anything but amused, California lawmakers imposed a $3 per month tax on foreigners, explicitly aimed at Chinese miners.

Large labor projects like the trans-continental railroad and Canadian Pacific Railway fed the influx of Chinese “coolie” labor, eager to work for wages too small to be of interest to American laborers.

By 1870, a full 25% of the California state budget came from that single tax on Chinese miners. In 1882, President Chester A. Arthur signed the Chinese Exclusion Act, prohibiting the further immigration of Chinese laborers. It was the first and remains to this day the only law specifically targeted at one ethnic group.

Meanwhile, the “gunboat diplomacy” of President Millard Fillmore determined to open Japanese ports to trade, with the west. By force, if necessary. By 1868, internal Japanese issues and the growing pressure of western encroachment had brought about the end of the Tokugawa Shōgunate and restoration of the Meiji Emperor.

The social changes wrought by the “Meiji Restoration” combined with abrupt opening to world trade plunged the Japanese economy, into recession. Japanese emigrants had left the home islands since the 15th century, in pursuit of new opportunities. That was nothing compared with the new “Japanese diaspora” begun in 1868. 3.8 million “Nikkei” emigrated between 1868 and 1912, bound for destinations from Brazil to mainland China, the United States, Australia, Peru, Germany and others. Even Finland.

These were the Issei, first generation immigrants, ineligible for citizenship under US law. The immigrant generation kept to the ways of the land they had left behind forming kenjin-kai, social and aid organizations built around the prefecture, from which they had come. Not so, the second generation. These were the Nisei, American-born US citizens, thoroughly assimilated to the culture to which their parents had arrived.

As with the earlier wave of Chinese immigrants, west coast European Americans became alarmed at the tide of Japanese immigration. Laws were passed and treaties signed, attempting to slow their number.

In 1908, an informal “Gentleman’s agreement” between the US and Japan prohibited further immigration of unskilled migrants. A loophole allowed wives to join their husbands already in the United States leading to an influx of “picture brides” – marriages arranged by friends and families and executed by proxy – many happy couples meeting for the first time, upon the arrival of the blushing bride. The immigration act of 1924 followed the example of the Chinese exclusion act of 1882, outright banning further immigration from “undesirable” Asian countries.

By this time 200,000 ethnic Japanese lived in Hawaii, mostly laborers looking for work on the island’s sugar plantations. A nearly equal number settled on the west coast building farms, and small businesses.

From 1937, the rapid conquests of the Asian Pacific raised fears that the Imperial Japanese military, was unstoppable. As relations soured between Japan and America, the Roosevelt administration took to surveillance of Japanese Americans, compiling lists.

Following the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, public sentiment came down largely on the side of Japanese Americans. The Los Angeles Times characterized them as “good Americans, born and educated as such,” but that would soon change. A member of the second attack wave on December 7, “Zero” pilot Shigenori Nishikaichi downed his crippled fighter on Ni’ihau, the westernmost island of the Hawaiian archipelago. Ignorant at first of what had taken place, Ni’hauans showed the downed pilot, hospitality. By the time it was over the whole thing turned violent, pitting the pilot and a small number of Issei and Nissei, in a deadly struggle against native Hawaiians.

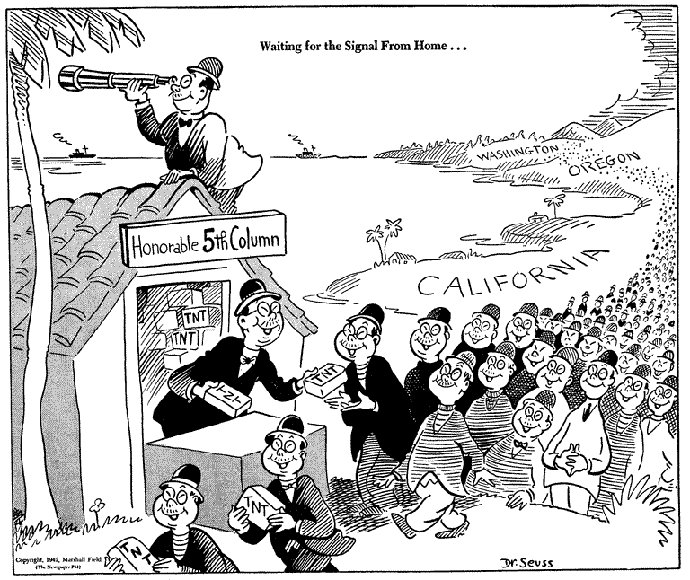

The “Ni’hau incident” combined with fears of 5th column activity to turn the tide, of public opinion.

General John Dewitt, a vocal proponent of what was about to happen, opined: “The fact that nothing has happened so far is more or less . . . ominous, in that I feel that in view of the fact that we have had no sporadic attempts at sabotage that there is a control being exercised and when we have it it will be on a mass basis”.

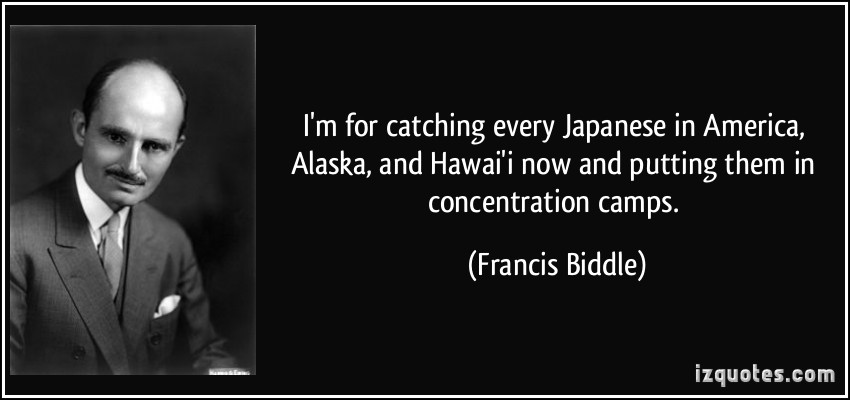

On January 2, a Joint Immigration Committee of the California legislature attacked “ethnic Japanese” citizen and non-citizen alike, as “totally unassimilable”. The presidentially appointed Roberts Committee assigned to investigate the attack on Pearl Harbor accused persons of Japanese ancestry of espionage, leading up to the attack. By February, California Attorney General and future Supreme Court Justice Earl Warren was doing everything he could to persuade the federal government, to remove all people of Japanese ancestry from the west coast.

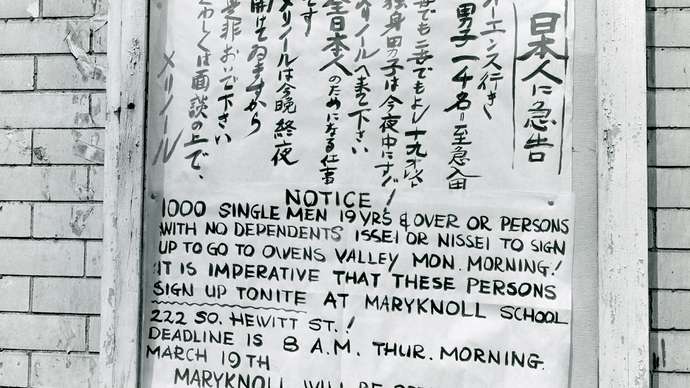

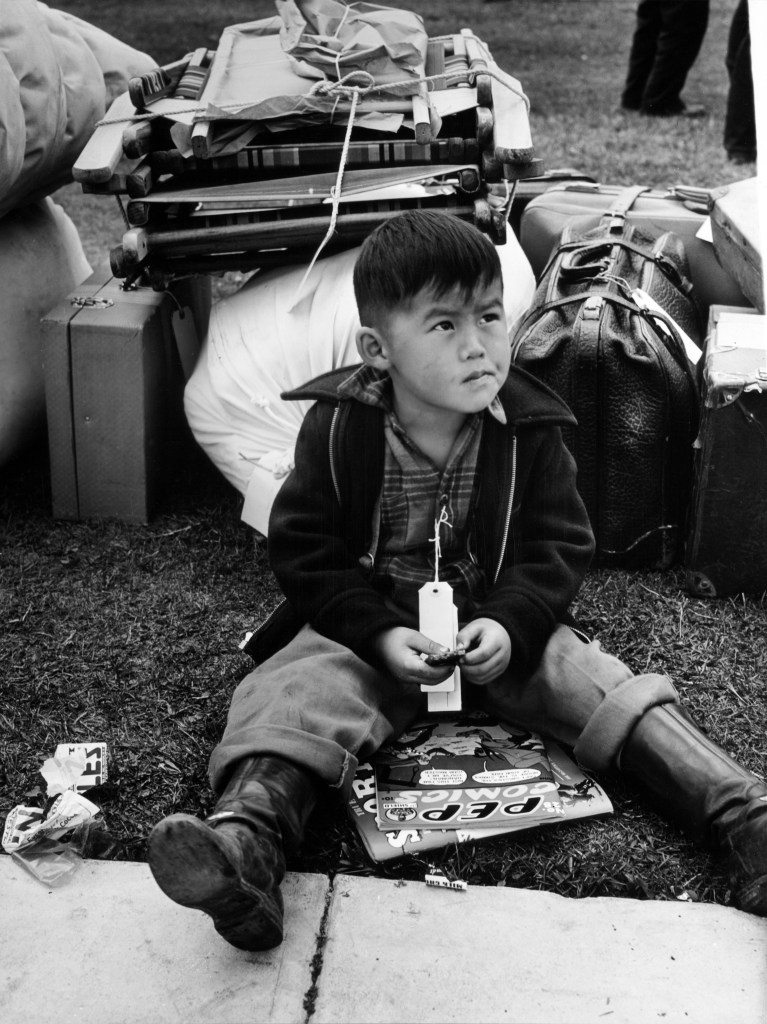

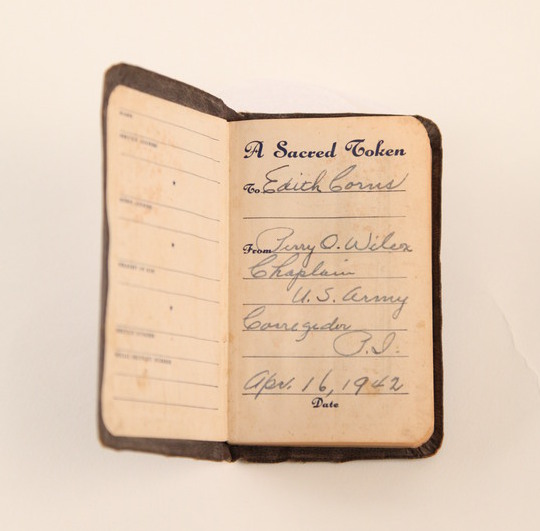

On January 14, 1942, President Roosevelt signed Proclamation 2537 requiring “enemy aliens” to procure identification and carry it with them, “at all times”. The War Department, and Department of Justice were sharply divided but, no matter. Executive order 9066 signed February 19 directed the establishment of exclusion zones.

Secret Presidential commissions were appointed in early 1941 and again in 1942, to determine the liklihood of an armed uprising among Japanese Americans. Both reported no evidence of such a thing, one reporting: “the local Japanese are loyal to the United States or, at worst, hope that by remaining quiet they can avoid concentration camps or irresponsible mobs.”

That didn’t matter, either. The Senate discussed Roosevelt’s directive for an hour and the House, for thirty minutes. The President signed Public Law 77-503 on March 21 providing for enforcement, of his earlier directive.

Roosevelt’s measure made no specific reference to ethnicity. Some 11,000 ethnic Germans and 3,000 ethnic Italians were sent away to internment camps but the vast preponderance, were of Japanese descent. Throughout the west coast some 112,000 ethnic Japanese were rounded up and held in relocation camps and other confinement areas, throughout the country. Surprisingly, only a “few thousand” were detained in Hawaii itself despite a population of nearly 40% ethnic Japanese.

Below: “A moving van being loaded with the possessions of a Japanese family on Bush Street in San Francisco’s Japantown, April 7, 1942. At right are the offices of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), the oldest Asian American civil rights organization in the United States. Shortly after this photo was taken, the Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA) took over the JACL building and repurposed it as a Civil Control Station for the collection and processing of “people of Japanese descent” prior to their transport to detention camps”.

H/T Encyclopedia Britannica

Following the events at Peal harbor, Oakland California-born Fred Korematsu attempted to enlist, in the Navy. Ostensibly rejected due to stomach ulcers, Korematsu believed the real reason was his Japanese ancestry. Korematsu refused deportation orders and went into hiding. The ACLU’s northern California director Ernest Besig brought Korematsu’s case before the courts despite opposition from Roosevelt allies in the national ACLU. Korematsu lost in federal court and the US court of appeals, becoming a pariah even among fellow detainees who felt he was nothing but a troublemaker. The US Supreme Court agreed to take the case and, on December 18, 1944, upheld the lower court verdict. A 6-3 opinion penned by Justice Hugo Black opined that, though suspect, internment was justified due to national circumstances of “emergency and peril”.

“Fourteen Days to Flatten the Curve, “ right?

A second decision released that same day in the case, Ex Parte Endo, unanimously declared it illegal to detain Americans, regardless of ethnicity. In effect the two rulings established that, while eviction was legal in the name of military necessity internment was not, thus paving the way to their release.

“There is but one way in which to regard the Presidential order empowering the Army to establish “military areas” from which citizens or aliens may be excluded. That is to accept the order as a necessary accompaniment of total defense”.

Washington Post, February 22, 1942

The Japs in these centers in the United States have been afforded the very best of treatment, together with food and living quarters far better than many of them ever knew before, and a minimum amount of restraint. They have been as well fed as the Army and as well as or better housed. . . . The American people can go without milk and butter, but the Japs will be supplied.

Los Angeles Times, December 8, 1942

Among internment camps many were eager to prove themselves, loyal Americans. Some were recruited for service in the armed forces. Many, volunteered. In April 1943 some 2,686 Japanese-Americans from Hawaii and 1,500 incarcerated in mainland camps, reported for duty at camp Shelby, in Mississippi. While many still had families in internment facilities, graduates were assigned to the segregated 442nd Regimental Combat team and sent off to fight the war, in Europe.

With something to prove every one of these guys, fought like tigers. From Naples to Rome to the south of France, to central Europe and the Po Valley, the all-Nisei 442nd infantry lived up to its own motto’ “Go for Broke”. 14,000 men served in the 442nd earning over 4,000 Purple Hearts, 4,000 Silver Stars, 4,000 Bronze Medals and 21 Medals of Honor.

With 275 Texas National Guardsmen hopelessly cut off by German forces in the Vosges Mountains of France, ‘The Lost Battalion”, the 442nd infantry was sent in to get them out. In five days of savage combat, 211 of the Texas men were rescued. The Nisei of the 442nd suffered 800 casualties. Of 185 men who entered the fray from I Company only 8 emerged, unhurt. Company K sent 186 men against the Germans 169 of whom were either killed, or wounded.

For its size and length of service the 442nd became the most highly decorated unit, in US military history.

Fun fact: Ralph Lazo was so angry at the forcible relocation of his friends he voluntarily joined them, on the train. Deported to the Manzanar concentration camp in the foot of California’s Sierra Nevada mountains, he stayed there, for two years. The only non-spouse, non-Japanese-American, so detained. Nobody ever asked the man about his ethnicity (half Mexican, half Irish). Lazo was inducted into the US Army in 1944 and served as a Staff Sergeant in the South Pacific where he earned a Bronze Star for valor, in combat.

By this time, many younger Nisei had left to pursue new lives, east of the Rockies. Seven others were shot and killed, by sentries. Older internees had little to return to with former homes and business, gone. Many were repatriated to Japan, at least some, against their will. By the end of 1945, nine of the top ten War Relocation Authority ( WRA) camps were shut down. Congress passed the Japanese-American claims Act in 1948 but, with the IRS having destroyed most of the detainees 1939-’42 tax records, only a fraction of claims were ever paid out.

By the late 1980s, powerful Japanese-American members of the United States Congress such as Bob Matsui, Norm Mineta and Spark Matsunaga spearheaded a measure, for reparations. $20,000 paid to every surviving internee. President Ronald Reagan signed the measure into law on August 10, 1988. Over 81,800 qualified, receiving a total of $1.6 Billion.

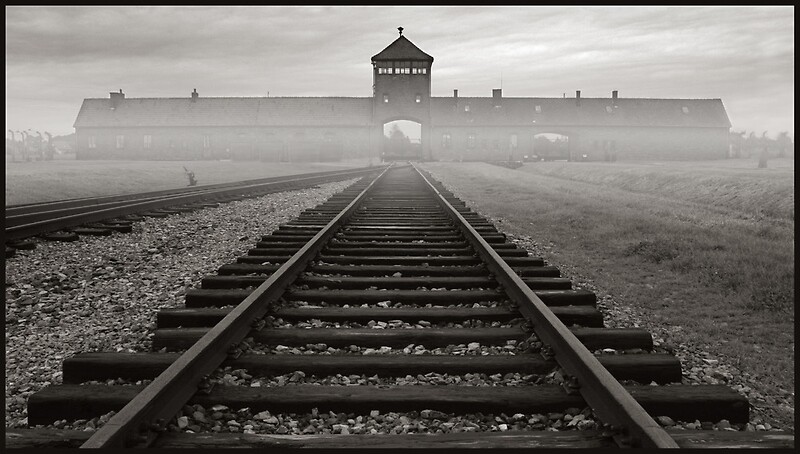

Circus-like performing dwarves were common enough at this time but the Ovitz siblings were different. These were talented musicians playing quarter-sized instruments, performing a variety show throughout the 1930s and early ’40s as the “Lilliput Troupe”. The family performed throughout Romania, Hungary and Czechoslovakia, with their normal height siblings serving as “roadies”. And then came the day. The whole lot of them were swept up by the Nazis and deported to the concentration camp and extermination center, at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Circus-like performing dwarves were common enough at this time but the Ovitz siblings were different. These were talented musicians playing quarter-sized instruments, performing a variety show throughout the 1930s and early ’40s as the “Lilliput Troupe”. The family performed throughout Romania, Hungary and Czechoslovakia, with their normal height siblings serving as “roadies”. And then came the day. The whole lot of them were swept up by the Nazis and deported to the concentration camp and extermination center, at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

On one occasion, the Angel of Death told the family they were “going to a beautiful place”. Terrified, the siblings were given makeup, and told to dress themselves. Brought to a nearby theater and placed onstage, the family must have thought they’d be asked to perform. Instead, Mengele ordered them to undress, leaving all seven naked before a room full of SS men. Mengele then gave a speech and invited the audience onstage, to poke and prod at the humiliated family.

On one occasion, the Angel of Death told the family they were “going to a beautiful place”. Terrified, the siblings were given makeup, and told to dress themselves. Brought to a nearby theater and placed onstage, the family must have thought they’d be asked to perform. Instead, Mengele ordered them to undress, leaving all seven naked before a room full of SS men. Mengele then gave a speech and invited the audience onstage, to poke and prod at the humiliated family.

Only 50 of the 650 Jewish inhabitants of the village ever returned. In 1949, the family emigrated to Israel and resumed their musical tour, performing until the group retired in 1955.

Only 50 of the 650 Jewish inhabitants of the village ever returned. In 1949, the family emigrated to Israel and resumed their musical tour, performing until the group retired in 1955.

The United States was grossly unprepared to fight a World War in 1942. The latest iteration of “War Plan Orange” (WPO-3) called for delaying tactics in the event of war with Japan, buying time to gather US Naval assets to sail for the Philippines. The problem was, there was no fleet to gather. The flower of American pacific power in the pacific, lay at the bottom of Pearl Harbor. Allied war planners turned their attention to defeating Adolf Hitler.

The United States was grossly unprepared to fight a World War in 1942. The latest iteration of “War Plan Orange” (WPO-3) called for delaying tactics in the event of war with Japan, buying time to gather US Naval assets to sail for the Philippines. The problem was, there was no fleet to gather. The flower of American pacific power in the pacific, lay at the bottom of Pearl Harbor. Allied war planners turned their attention to defeating Adolf Hitler. Japanese guards were sadistic. They would beat marchers and bayonet those too weak to walk. Tormented by a thirst few among us can so much as imagine, men were made to stand for hours under a relentless sun, standing by a stream from which none were permitted to drink. The man who broke ranks and dove for the water was clubbed or bayoneted to death, on the spot. Japanese tanks would swerve out of their way to run over anyone who had fallen and was too slow in getting up. Some were burned alive, others buried alive. Already crippled from tropical disease and starving from the long siege of Luzon, w

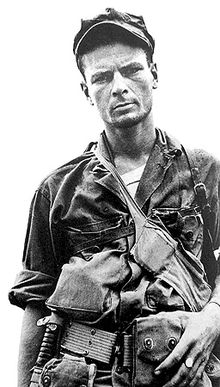

Japanese guards were sadistic. They would beat marchers and bayonet those too weak to walk. Tormented by a thirst few among us can so much as imagine, men were made to stand for hours under a relentless sun, standing by a stream from which none were permitted to drink. The man who broke ranks and dove for the water was clubbed or bayoneted to death, on the spot. Japanese tanks would swerve out of their way to run over anyone who had fallen and was too slow in getting up. Some were burned alive, others buried alive. Already crippled from tropical disease and starving from the long siege of Luzon, w United States Marine Corps 1st Lieutenant Austin Shofner came ashore back in November, with the 4th Marines. Shofner and his fellow leathernecks engaged the Japanese as early as December 12 and received their first taste of aerial bombardment, on December 29. Promoted to Captain and placed in command of Headquarters Company, Shofner received two Silver Stars by April 15 in near-constant defense against aerial attack.

United States Marine Corps 1st Lieutenant Austin Shofner came ashore back in November, with the 4th Marines. Shofner and his fellow leathernecks engaged the Japanese as early as December 12 and received their first taste of aerial bombardment, on December 29. Promoted to Captain and placed in command of Headquarters Company, Shofner received two Silver Stars by April 15 in near-constant defense against aerial attack.

Nearly 150,000 Allied soldiers were taken captive by the Japanese Empire, during World War 2. Clad in unspeakably filthy rags they were fed a mere 600 calories per day of fouled rice, supplemented only by the occasional insect or bird or rodent unlucky enough to fall into desperate hands. Disease such as malaria was all but universal as gross malnutrition led to loss of vision and unrelenting nerve pain. Dysentery, a hideously infectious disease of the large intestine reduced grown men to animated skeletons. Mere scratches resulted in grotesque tropical ulcers up to a foot in length exposing living bone and rotting flesh to swarms of ravenous insects.

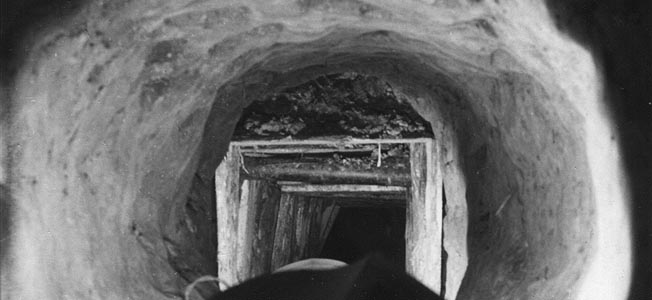

Nearly 150,000 Allied soldiers were taken captive by the Japanese Empire, during World War 2. Clad in unspeakably filthy rags they were fed a mere 600 calories per day of fouled rice, supplemented only by the occasional insect or bird or rodent unlucky enough to fall into desperate hands. Disease such as malaria was all but universal as gross malnutrition led to loss of vision and unrelenting nerve pain. Dysentery, a hideously infectious disease of the large intestine reduced grown men to animated skeletons. Mere scratches resulted in grotesque tropical ulcers up to a foot in length exposing living bone and rotting flesh to swarms of ravenous insects. Given such cruel conditions it’s a wonder anyone escaped at all but it did happen. Once.

Given such cruel conditions it’s a wonder anyone escaped at all but it did happen. Once.

Now-Colonel Shofner volunteered to return to the Pacific where his experience helped with the rescue of 500 prisoners of the infamous POW camp at Cabanatuan on January 30, 1945.

Now-Colonel Shofner volunteered to return to the Pacific where his experience helped with the rescue of 500 prisoners of the infamous POW camp at Cabanatuan on January 30, 1945.

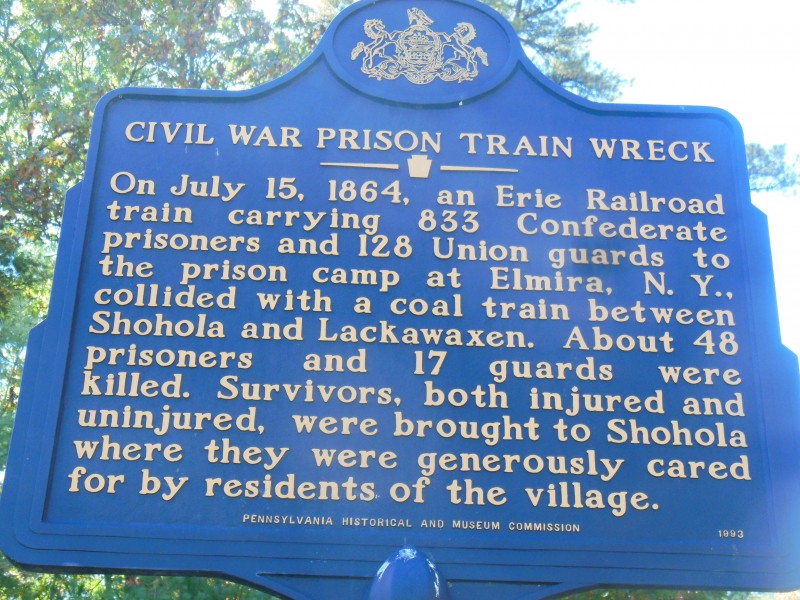

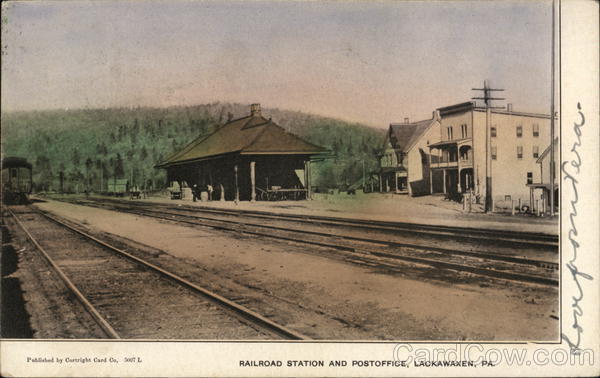

Erie Engine #237 arrived at Lackawaxen at 2:30 pm pulling 50 coal cars, loaded for Jersey City. Kent gave the all clear at 2:45. The main switch was opened, and Erie #237 joined the single track heading east out of Shohola.

Erie Engine #237 arrived at Lackawaxen at 2:30 pm pulling 50 coal cars, loaded for Jersey City. Kent gave the all clear at 2:45. The main switch was opened, and Erie #237 joined the single track heading east out of Shohola. “[T]he wooden coaches telescoped into one another, some splitting open and strewing their human contents onto the berm, where flying glass, splintered wood, and jagged metal killed or injured them as they rolled. Other occupants were hurled through windows or pitched to the track as the car floors buckled and opened. The two ruptured engine tenders towered over the wreckage, their massive floor timbers snapped like matchsticks. Driving rods were bent like wire. Wheels and axles lay broken. The troop train’s forward boxcar had been compacted and within the remaining mass were the remains of 37 men”. Witnesses saw “headless trunks, mangled between the telescoped cars” and “bodies impaled on iron rods and splintered beams.”

“[T]he wooden coaches telescoped into one another, some splitting open and strewing their human contents onto the berm, where flying glass, splintered wood, and jagged metal killed or injured them as they rolled. Other occupants were hurled through windows or pitched to the track as the car floors buckled and opened. The two ruptured engine tenders towered over the wreckage, their massive floor timbers snapped like matchsticks. Driving rods were bent like wire. Wheels and axles lay broken. The troop train’s forward boxcar had been compacted and within the remaining mass were the remains of 37 men”. Witnesses saw “headless trunks, mangled between the telescoped cars” and “bodies impaled on iron rods and splintered beams.”

As the years went by, signs of all those graves were erased. Hundreds of trains carried thousands of passengers up and down the Erie Railroad, ignorant of the burial ground through which they passed.

As the years went by, signs of all those graves were erased. Hundreds of trains carried thousands of passengers up and down the Erie Railroad, ignorant of the burial ground through which they passed.

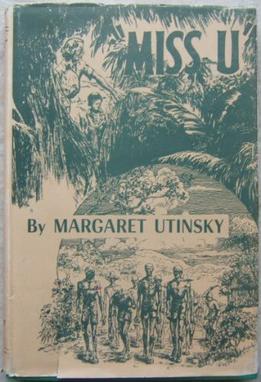

“To go into an internment camp seemed like the sensible thing to do, but for the life of me I could not see what use I would be to myself or to anyone else cooped up there. … For from the moment the inconceivable thing happened and the Japanese arrived, there was just one thought in my mind—to find Jack.”

“To go into an internment camp seemed like the sensible thing to do, but for the life of me I could not see what use I would be to myself or to anyone else cooped up there. … For from the moment the inconceivable thing happened and the Japanese arrived, there was just one thought in my mind—to find Jack.”

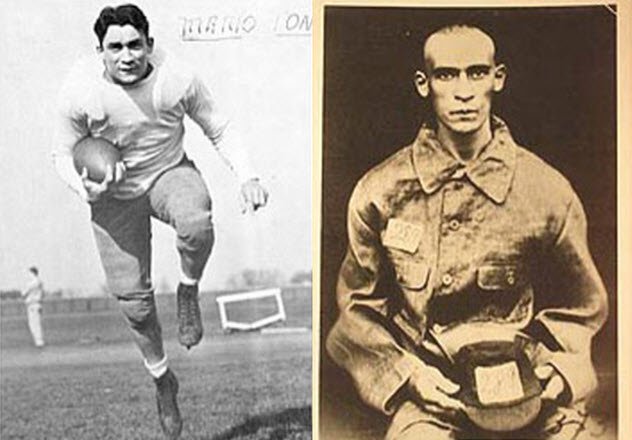

In some ways, Mario Tonelli himself was the miracle. Years earlier at the age of 6, he’d been burned over 80% of his body, when a trash compactor toppled over on him. Mario’s immigrant father Celi, a laborer from a northern Italian marble quarry, refused to believe the doctor who said his son would never walk again. Fixing four wheels to a door, the elder Tonelli taught his first American-born son to move about with his arms.

In some ways, Mario Tonelli himself was the miracle. Years earlier at the age of 6, he’d been burned over 80% of his body, when a trash compactor toppled over on him. Mario’s immigrant father Celi, a laborer from a northern Italian marble quarry, refused to believe the doctor who said his son would never walk again. Fixing four wheels to a door, the elder Tonelli taught his first American-born son to move about with his arms.

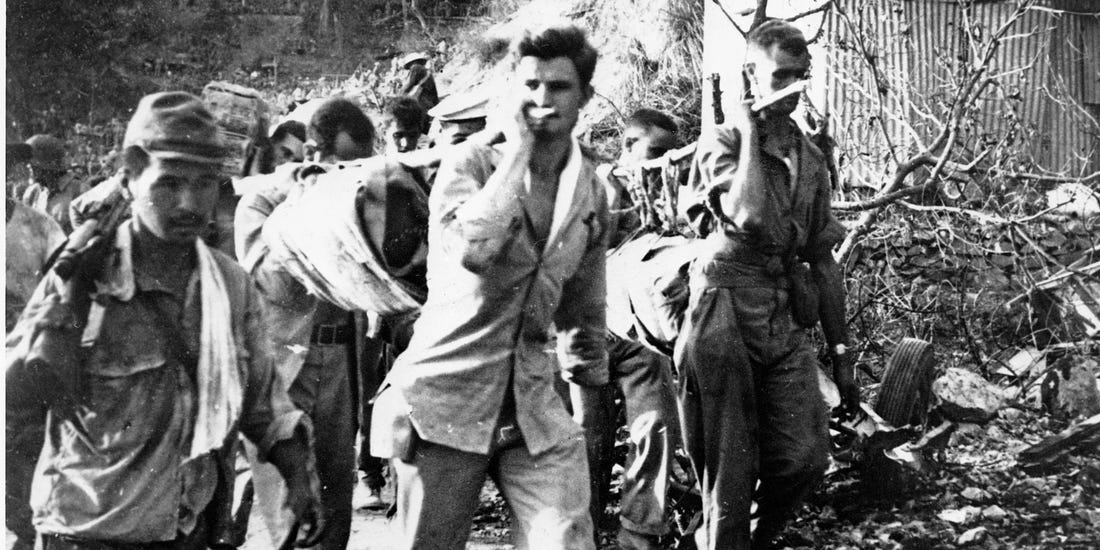

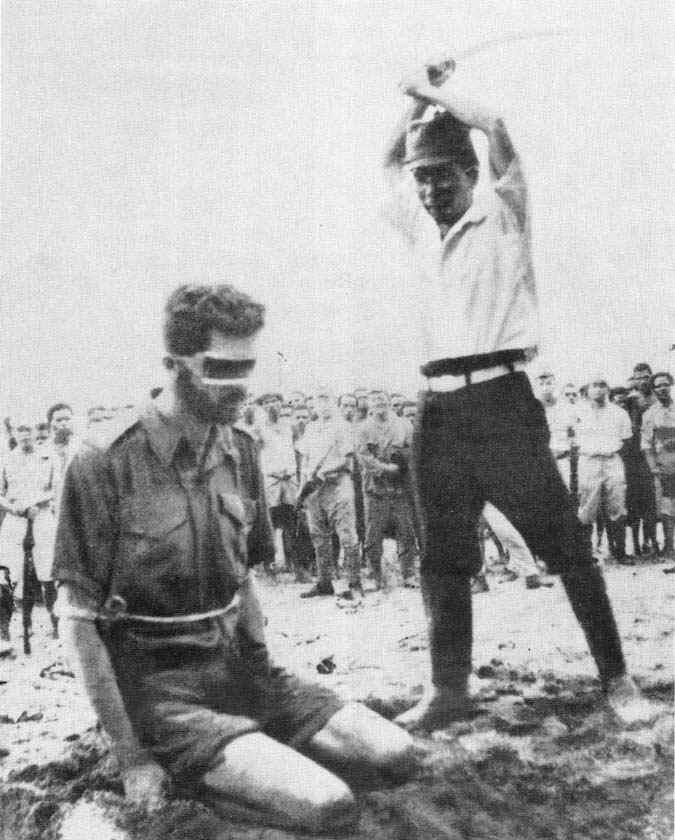

On April 9, 75,000 surrendered the Bataan peninsula, beginning a 65 mile, five-day slog into captivity through the heat of the Philippine jungle. Japanese guards were sadistic. Some would beat the marchers at random, or bayonet those too weak to walk. Japanese tanks would swerve out of the way to run over anyone who had fallen and was too slow in getting up. Some were burned alive. Already crippled from tropical disease and starving from the long siege of Luzon, thousands perished in what came to be known as the Bataan Death March.

On April 9, 75,000 surrendered the Bataan peninsula, beginning a 65 mile, five-day slog into captivity through the heat of the Philippine jungle. Japanese guards were sadistic. Some would beat the marchers at random, or bayonet those too weak to walk. Japanese tanks would swerve out of the way to run over anyone who had fallen and was too slow in getting up. Some were burned alive. Already crippled from tropical disease and starving from the long siege of Luzon, thousands perished in what came to be known as the Bataan Death March.

An American military tribunal conducted after the war held Lieutenant General Homma Masaharu, commander of the Japanese invasion forces in the Philippines, guilty of war crimes. He was executed by firing squad on April 3, 1946.

An American military tribunal conducted after the war held Lieutenant General Homma Masaharu, commander of the Japanese invasion forces in the Philippines, guilty of war crimes. He was executed by firing squad on April 3, 1946.

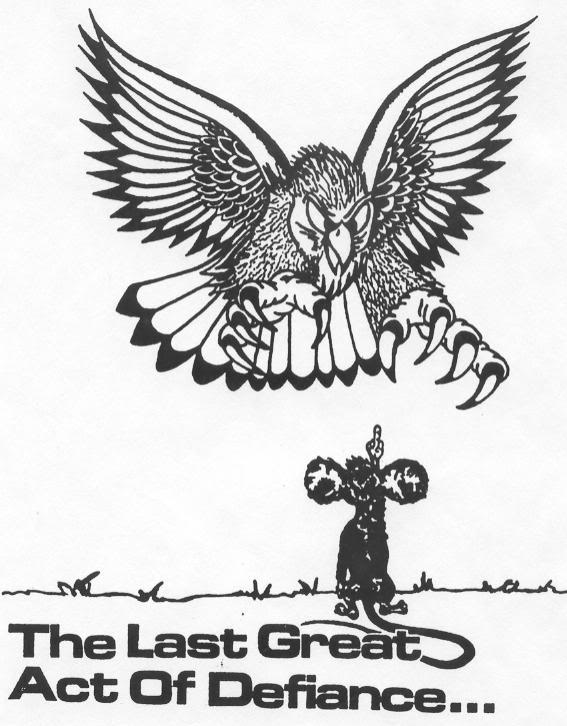

Before the age of the internet meme, office jokes and bits of folk wisdom were passed around and copied and copied again. There was one, “The Last great of Defiance“, which will live for all time as my favorite. The picture speaks for itself. I had one on the wall, for years.

Before the age of the internet meme, office jokes and bits of folk wisdom were passed around and copied and copied again. There was one, “The Last great of Defiance“, which will live for all time as my favorite. The picture speaks for itself. I had one on the wall, for years. Prisoners were swept up by the thousands, and faced an uncertain future. In Malmedy, Belgium, seventy-five captured Americans were marched into an open field and machine gunned by members of the 1st SS Panzer Division (Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler), a part of 6th Panzer Army.

Prisoners were swept up by the thousands, and faced an uncertain future. In Malmedy, Belgium, seventy-five captured Americans were marched into an open field and machine gunned by members of the 1st SS Panzer Division (Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler), a part of 6th Panzer Army.

Captured at Spotsylvania in early 1864, 52nd North Carolina Infantry private James Tyner was incarcerated at the Elmira camp at this time. Tyner’s brother William was one of the prisoners on board #171.

Captured at Spotsylvania in early 1864, 52nd North Carolina Infantry private James Tyner was incarcerated at the Elmira camp at this time. Tyner’s brother William was one of the prisoners on board #171.

You must be logged in to post a comment.