In 1944, Texas political Boss George Berham Parr and Webb County Judge Manuel “Black  Hawk” Raymond had a favor to ask of then-Governor Coke Robert Stevenson. They wanted the Governor to appoint a Raymond relative, E. James Kazen, as Laredo district attorney.

Hawk” Raymond had a favor to ask of then-Governor Coke Robert Stevenson. They wanted the Governor to appoint a Raymond relative, E. James Kazen, as Laredo district attorney.

The Governor wasn’t playing ball. The United States was at war at that time, and the commander at the local Army Air Force Base opposed the appointment, saying that half his men were down with VD. A district attorney from the local political machine, he argued, would mean lax enforcement of prostitution laws, and his high sick rate was adversely effecting the war effort.

Stevenson was persuaded, and he appointed another man to the job. George Parr would not forget the slight.

Four years later, Coke Stevenson was running for the United States Senate. Parr had a debt to repay to Stevenson’s opponent, Congressman Lyndon Baynes Johnson, who had helped him obtain a Presidential Pardon back in 1946. He had some payback to do on Stevenson’s account as well, but that would be payback of a different sort.

Texas had only a weak Republican party in 1948. The winner of the Democrat’s three-way primary was sure to be the next Senator.

Texas had only a weak Republican party in 1948. The winner of the Democrat’s three-way primary was sure to be the next Senator.

When the votes were counted on August 28, Stevenson was the top vote getter with 37.3%, edging out Johnson at #2, by 112 votes out of 988,295 cast.

Texas state law requires an absolute majority to determine a primary winner, so a runoff was held between the top two finishers.

Stevenson held the lead at the end of counting. Five days later, Jim Wells County amended its return. 202 additional votes had been “found”, hidden away in Box #13 from the town of Alice.

200 of the 202 had voted for Johnson. By a miraculous coincidence, each had signed their names in alphabetical order, in the same penmanship, each apparently using the same pen.

An investigation was called, and the executive committee of the Texas Democratic Party upheld Johnson’s victory, 29-to-28. Stevenson sued.

A Federal court ordered Johnson’s name off the ballot pending the results of an investigation, but the matter was settled in Johnson’s favor when Associate Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black voided the order on the urging of Johnson lawyer, Abe Fortas.

Purely coincidentally I’m sure, the very same Abe Fortas would himself be appointed to the Supreme Court by then-President Lyndon Johnson, in 1965.

Johnson went on to defeat the Republican candidate in the general election. The primary ballots were “accidentally” burned some time later.

‘Means of Ascent’ author Robert A. Caro, the second volume of a projected four-volume Johnson study entitled ‘The Years of Lyndon Johnson’, told the New York Times in a 1990 interview: ‘People have been saying for 40 years, ‘No one knows what really happened in that election,’ and ‘Everybody does it.’ Neither of those statements is true. I don’t think that this is the only election that was ever stolen, but there was never such brazen thievery”.

LBJ had “won” his primary by 87 votes, August 28 forever marking the day on which he would be known as “landslide Lyndon”. Johnson easily defeated Republican Jack Porter for the Senate seat, later becoming Vice President and then President after the  assassination of John F Kennedy, a man whom many believe stole his own election from Richard Nixon in 1960, with the help of Chicago’s Daley machine and a little creative vote counting in Cook County.

assassination of John F Kennedy, a man whom many believe stole his own election from Richard Nixon in 1960, with the help of Chicago’s Daley machine and a little creative vote counting in Cook County.

Johnson never acknowledged stealing the election, but Ronnie Dugger, editor of the Texas Observer, once visited him in the White House. Then-President Johnson pulled out a photo of five “ol’ boys” from Alice, grinning back at the camera with the infamous Box 13 between them. Dugger asked LBJ if he had stolen the election. President Johnson’s only response, was to laugh.

104 years ago today, 1,700 seasonal hops pickers gathered in the field of the Durst Hop Farm. They demanded an increase from their $1.00/100 lbs of hops picked, and they wanted better working conditions. Durst agreed to some changes, but Ford and Suhr stuck to their full list of demands and called a strike.

104 years ago today, 1,700 seasonal hops pickers gathered in the field of the Durst Hop Farm. They demanded an increase from their $1.00/100 lbs of hops picked, and they wanted better working conditions. Durst agreed to some changes, but Ford and Suhr stuck to their full list of demands and called a strike.

More shooting incidents occurred in the days that followed. Objections to the whiskey tax gave way to a long list of economic grievances, as over 7,000 gathered in Braddock’s Field on August 1. They talked of secession and carried their own flag, each of its six stripes representing one of 6 Pennsylvania or eastern Ohio counties.

More shooting incidents occurred in the days that followed. Objections to the whiskey tax gave way to a long list of economic grievances, as over 7,000 gathered in Braddock’s Field on August 1. They talked of secession and carried their own flag, each of its six stripes representing one of 6 Pennsylvania or eastern Ohio counties. The whiskey rebellion collapsed in the face of what was then an overwhelming army, with 10 of their leaders brought to Philadelphia to stand trial. Two were sentenced to hang for their role in the rebellion, but President Washington pardoned them both. The whiskey rebellion was over.

The whiskey rebellion collapsed in the face of what was then an overwhelming army, with 10 of their leaders brought to Philadelphia to stand trial. Two were sentenced to hang for their role in the rebellion, but President Washington pardoned them both. The whiskey rebellion was over.

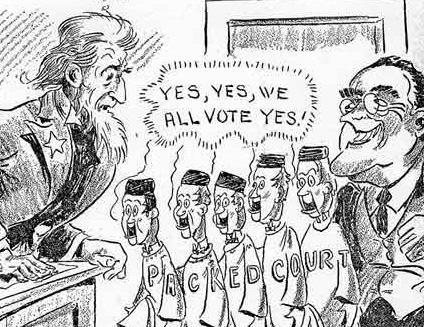

Realist” or “Liberal” legal scholars and judges argued that the constitution was a “living document”, allowing for judicial flexibility and legislative experimentation. Supreme Court justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., a leading proponent of the Realist philosophy, said of Missouri v. Holland that the “case before us must be considered in the light of our whole experience and not merely in that of what was said a hundred years ago”.

Realist” or “Liberal” legal scholars and judges argued that the constitution was a “living document”, allowing for judicial flexibility and legislative experimentation. Supreme Court justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., a leading proponent of the Realist philosophy, said of Missouri v. Holland that the “case before us must be considered in the light of our whole experience and not merely in that of what was said a hundred years ago”. To Roosevelt, that was the answer. The age 70 provision allowed him 6 more handpicked justices, effectively ending Supreme Court opposition to his policies.

To Roosevelt, that was the answer. The age 70 provision allowed him 6 more handpicked justices, effectively ending Supreme Court opposition to his policies.

The states turned over control of immigration to the Federal Government in 1890, and an immigration control office was opened on a Barge on the Battery at the tip of Manhattan.

The states turned over control of immigration to the Federal Government in 1890, and an immigration control office was opened on a Barge on the Battery at the tip of Manhattan.

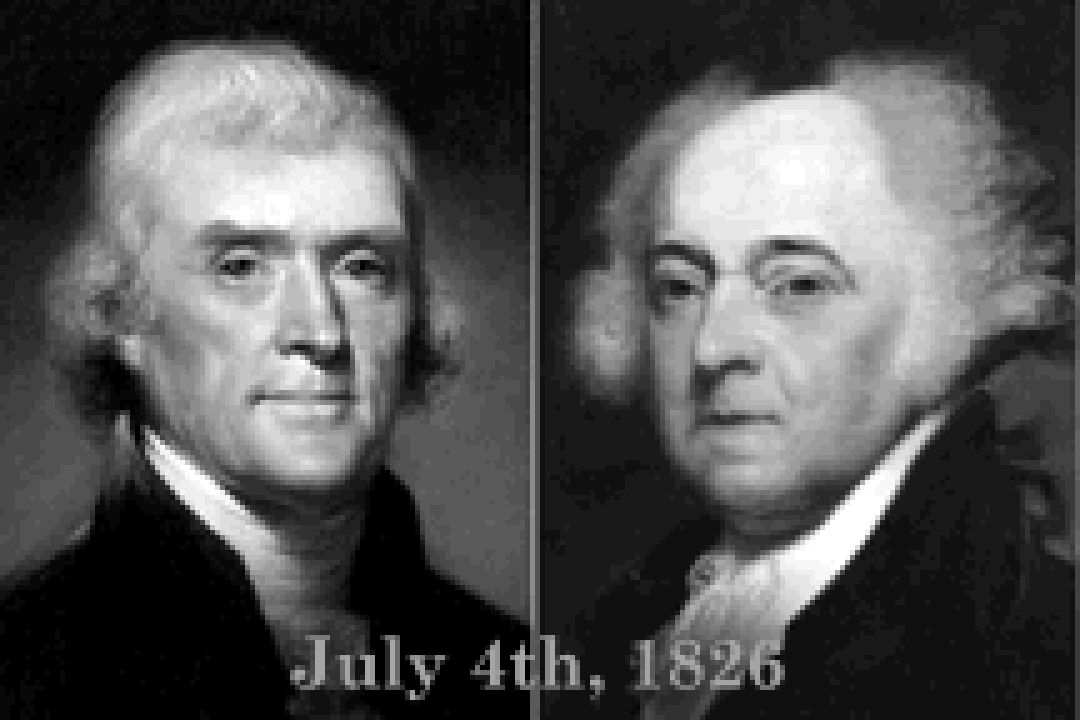

Representatives agreed to delay the vote until July 1, appointing a “Committee of Five” to draft a declaration of independence from Great Britain. Members of the committee included John Adams of Massachusetts, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Roger Sherman of Connecticut, Robert Livingston of New York and Thomas Jefferson of Virginia. The committee selected Jefferson to write the document, the draft presented to Congress for review on June 28.

Representatives agreed to delay the vote until July 1, appointing a “Committee of Five” to draft a declaration of independence from Great Britain. Members of the committee included John Adams of Massachusetts, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Roger Sherman of Connecticut, Robert Livingston of New York and Thomas Jefferson of Virginia. The committee selected Jefferson to write the document, the draft presented to Congress for review on June 28.

You must be logged in to post a comment.