Margaretha Geertruida Zelle was born in the Netherlands on August 7, 1876, the eldest of four children. “M’greet” to family and friends, she answered a newspaper ad placed by Dutch Colonial Army Captain Rudolf MacLeod, then stationed in the Dutch East Indies, in modern day Indonesia.

She’d come from a broken home. Being a “mail order bride” must have seemed like the way to financial security. The marriage was a disappointment, MacLeod was a drunk and openly kept a mistress. Margaretha moved in with another Dutch officer some time in 1897.

Despite problems at home, the Dutch mail order bride found herself moving among the upper classes. She immersed herself in Indonesian culture and traditions, even joining a local dance company. It was around this time that she revealed her “artistic” name in letters home: “Mata Hari”, Indonesian for “sun” (literally, “eye of the day”), in Sanskrit.

Despite problems at home, the Dutch mail order bride found herself moving among the upper classes. She immersed herself in Indonesian culture and traditions, even joining a local dance company. It was around this time that she revealed her “artistic” name in letters home: “Mata Hari”, Indonesian for “sun” (literally, “eye of the day”), in Sanskrit.

Margaretha Zelle was divorced by 1905, and becoming known as an exotic dancer. She was a contemporary of dancers Isadora Duncan and Ruth St. Denis, leaders in the early modern dance movement. As Mata Hari, she played the more exotic aspects of her background to the hilt, projecting a bold and in-your-face sexuality that was unique and provocative for her time.

She claimed to be a Java princess of priestly Hindu birth, immersed since childhood in the sacred art of Indian dance. Carefree and thoroughly uninhibited, she was photographed in the nude or the next thing to it on many occasions during this period, becoming the long-time mistress of the millionaire Lyon industrialist Émile Étienne Guimet.

The world stood still at the beginning of World War I, but not Margaretha Zelle. By 1914 her dancing days were over, but she was a famous courtesan, moving among the highest social and economic levels of her time. Her neutral Dutch citizenship allowed her to move about without restriction, but not without a price. Zelle’s movements brought her under suspicion of being a German Agent, and she was arrested in the English port of Falmouth. She was taken to Scotland Yard for interrogation in 1916, but later released.

French authorities arrested her on February 13, 1917, in her room at the Hotel Elysee Palace, in what is now the banking giant HSBC’s French headquarters. She was kept in prison as the case was prepared against her, all the while writing to the Dutch Consul in Paris, proclaiming her innocence. “My international connections are due to my work as a dancer, nothing else”, she wrote. “I really did not spy, it is terrible that I cannot defend myself”.

Her defense attorney, Edouard Clunet, never really had a chance. He couldn’t cross examine the prosecution’s witnesses or even directly question his own. Her conviction was a foregone conclusion.

Margaretha Geertruida Zelle was executed by a French firing squad on October 15, 1917. She was 41.

British reporter Henry Wales described the execution, based on an eyewitness account. Unbound and refusing a blindfold, Mata Hari stood alone to face her firing squad. After the shots rang out, Wales reported that “Slowly, inertly, she settled to her knees, her head up always, and without the slightest change of expression on her face. For the fraction of a second it seemed she tottered there, on her knees, gazing directly at those who had taken her life. Then she fell backward, bending at the waist, with her legs doubled up beneath her.”

British reporter Henry Wales described the execution, based on an eyewitness account. Unbound and refusing a blindfold, Mata Hari stood alone to face her firing squad. After the shots rang out, Wales reported that “Slowly, inertly, she settled to her knees, her head up always, and without the slightest change of expression on her face. For the fraction of a second it seemed she tottered there, on her knees, gazing directly at those who had taken her life. Then she fell backward, bending at the waist, with her legs doubled up beneath her.”

An NCO walked up to her body, pulled out his revolver, and shot her in the head to make sure she was dead.

German documents unsealed in the 1970s indicate that Mata Hari did, in fact, provide information to German authorities, though it seems to have been of limited use. It is possible to believe that she was little more than a young woman, with a fondness for men in uniform. French authorities built her up as “the greatest woman spy of the century”, though that may have been little more than covering up for their own disastrous performance in the Nivelle offensive.

French officers from whom she ostensibly got all that information, seem not to have been questioned.

The whole truth may never be known, but the tale of the real-life exotic dancer working as a lethal double agent, is a story that’s hard to resist.

Great believers in the perfectibility of the public sphere, Progressives eschewed old methods as wasteful and inefficient, leaning instead toward the advice of academics and “experts”, looking for that “one best way” to get things done.

Great believers in the perfectibility of the public sphere, Progressives eschewed old methods as wasteful and inefficient, leaning instead toward the advice of academics and “experts”, looking for that “one best way” to get things done. Roosevelt retired from politics after two terms to go on African safari, backing William Howard Taft for the Republican nomination.

Roosevelt retired from politics after two terms to go on African safari, backing William Howard Taft for the Republican nomination.

For a time, Norton disappeared from the public eye. In September 1859, he proclaimed himself Emperor of the United States, his Royal Ascension announced to the public in a letter to the editor of the San Francisco Bulletin. “At the peremptory request and desire of a large majority of the citizens”, it read, “I, Joshua Norton…declare and proclaim myself Emperor of these United States.” The letter went on to command representatives from all the states to convene in San Francisco, “to make such alterations in the existing laws of the Union as may ameliorate the evils under which the country is laboring.”

For a time, Norton disappeared from the public eye. In September 1859, he proclaimed himself Emperor of the United States, his Royal Ascension announced to the public in a letter to the editor of the San Francisco Bulletin. “At the peremptory request and desire of a large majority of the citizens”, it read, “I, Joshua Norton…declare and proclaim myself Emperor of these United States.” The letter went on to command representatives from all the states to convene in San Francisco, “to make such alterations in the existing laws of the Union as may ameliorate the evils under which the country is laboring.” That December, Norton fired Virginia Governor Henry Wise for hanging abolitionist John Brown, appointing then-vice President John C. Breckinridge in his stead.

That December, Norton fired Virginia Governor Henry Wise for hanging abolitionist John Brown, appointing then-vice President John C. Breckinridge in his stead. Norton wore an elaborate blue uniform with gold epaulettes, carrying a cane or saber and topped off with beaver hat with peacock feather. By day he “inspected” the streets and public works of San Francisco, by night he would dine in the city’s finest establishments. No play or musical performance would dare open in the city, without reserved balcony seats for Emperor Norton.

Norton wore an elaborate blue uniform with gold epaulettes, carrying a cane or saber and topped off with beaver hat with peacock feather. By day he “inspected” the streets and public works of San Francisco, by night he would dine in the city’s finest establishments. No play or musical performance would dare open in the city, without reserved balcony seats for Emperor Norton. In 1867, police officer Armand Barbier arrested Norton, attempting to have him involuntarily committed to an insane asylum. The public backlash was so vehement that Police Chief Patrick Crowley ordered Norton’s release and issued a public apology. The episode ended well, when Emperor Norton magnanimously pardoned the police department. After that, San Francisco cops saluted Emperor Norton whenever meeting him in the street.

In 1867, police officer Armand Barbier arrested Norton, attempting to have him involuntarily committed to an insane asylum. The public backlash was so vehement that Police Chief Patrick Crowley ordered Norton’s release and issued a public apology. The episode ended well, when Emperor Norton magnanimously pardoned the police department. After that, San Francisco cops saluted Emperor Norton whenever meeting him in the street. The San Francisco Board of Supervisors once bought him a new uniform, when the old one got too shabby. Norton responded with a very nice thank you note, issuing each of them a “Patent of Nobility in Perpetuity”.

The San Francisco Board of Supervisors once bought him a new uniform, when the old one got too shabby. Norton responded with a very nice thank you note, issuing each of them a “Patent of Nobility in Perpetuity”.

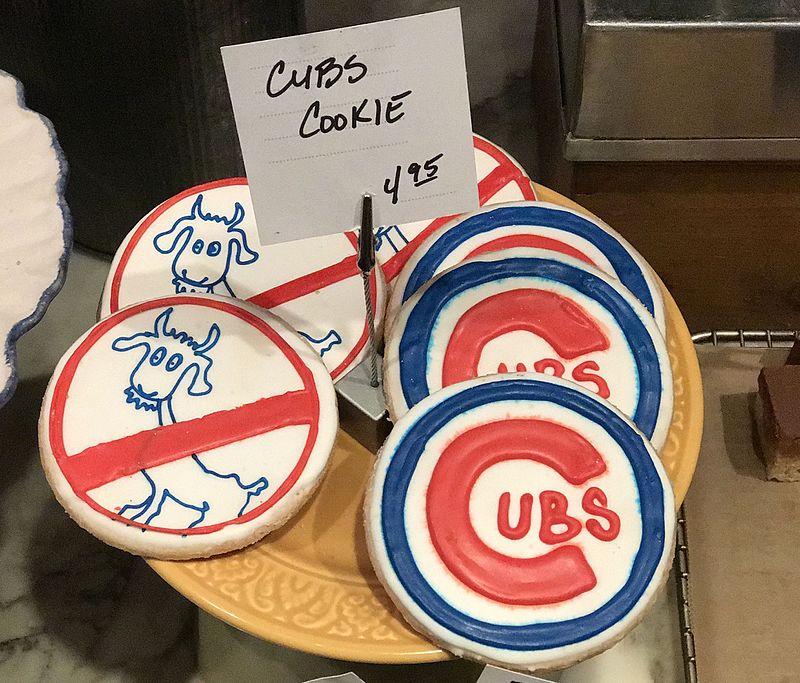

It was game four of the World Series between the Cubbies and the Detroit Tigers, October 6, 1945, with Chicago home at Wrigley Field. Billy Sianis, owner of the Billy Goat Tavern in Chicago, bought tickets for himself and his pet goat “Murphy”. Anyone who’s ever found himself in the company of a goat understands the problem. Right?

It was game four of the World Series between the Cubbies and the Detroit Tigers, October 6, 1945, with Chicago home at Wrigley Field. Billy Sianis, owner of the Billy Goat Tavern in Chicago, bought tickets for himself and his pet goat “Murphy”. Anyone who’s ever found himself in the company of a goat understands the problem. Right? Billy Sianis was right. The Cubs were up two games to one at the time, but they went on to lose the series. They’ve been losing ever since.

Billy Sianis was right. The Cubs were up two games to one at the time, but they went on to lose the series. They’ve been losing ever since. Alou slammed his glove down in anger and frustration. Pitcher Mark Prior glared at the stands, crying “fan interference”. The Marlins came back with 8 unanswered runs in the inning. Steve Bartman required a police escort to get out of the field alive.

Alou slammed his glove down in anger and frustration. Pitcher Mark Prior glared at the stands, crying “fan interference”. The Marlins came back with 8 unanswered runs in the inning. Steve Bartman required a police escort to get out of the field alive.

The mother of all droughts came to a halt on November 2 in a ten-inning cardiac arrest that had us all up Way past midnight, on a school night. I even watched that 17-minute rain delay, and I’m a Red Sox guy.

The mother of all droughts came to a halt on November 2 in a ten-inning cardiac arrest that had us all up Way past midnight, on a school night. I even watched that 17-minute rain delay, and I’m a Red Sox guy.

Pitchers Eddie Cicotte and Claude “Lefty” Williams, along with outfielder Oscar “Hap” Felsch, and shortstop Charles “Swede” Risberg were all principally involved with fixing the series. Third baseman George “Buck” Weaver was at a meeting where the fix was discussed, but decided not to participate. Weaver handed in some of his best statistics of the year during the Series.

Pitchers Eddie Cicotte and Claude “Lefty” Williams, along with outfielder Oscar “Hap” Felsch, and shortstop Charles “Swede” Risberg were all principally involved with fixing the series. Third baseman George “Buck” Weaver was at a meeting where the fix was discussed, but decided not to participate. Weaver handed in some of his best statistics of the year during the Series. Rumors were flying when the series started on October 2. So much money was on Cincinnati that the odds were flat. Gamblers complained that nothing was left on the table. Williams lost his three games in the best-out-of nine series, which I believe stands as a World Series record to this day. Cicotte became angry, thinking that gamblers were trying to renege, and he bore down, the White Sox winning game 7.

Rumors were flying when the series started on October 2. So much money was on Cincinnati that the odds were flat. Gamblers complained that nothing was left on the table. Williams lost his three games in the best-out-of nine series, which I believe stands as a World Series record to this day. Cicotte became angry, thinking that gamblers were trying to renege, and he bore down, the White Sox winning game 7. Ironically, the 1919 scandal would lead to a White Sox crash in the 1921 season, beginning the “Curse of the Black Sox”. It was a World Series championship drought that lasted 88 years, ending only in 2005, with a sweep of the Houston Astros. Exactly one year after the Boston Red Sox ended their own 86-year drought, the “Curse of the Bambino”.

Ironically, the 1919 scandal would lead to a White Sox crash in the 1921 season, beginning the “Curse of the Black Sox”. It was a World Series championship drought that lasted 88 years, ending only in 2005, with a sweep of the Houston Astros. Exactly one year after the Boston Red Sox ended their own 86-year drought, the “Curse of the Bambino”.

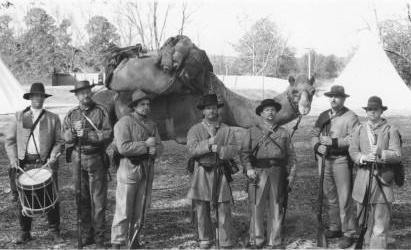

The story begins with Jefferson Davis, in the 1840s. Now we remember him as the President of the Confederate States of America. Then, he was a United States Senator from Mississippi, with a pet project of introducing camels into the United States.

The story begins with Jefferson Davis, in the 1840s. Now we remember him as the President of the Confederate States of America. Then, he was a United States Senator from Mississippi, with a pet project of introducing camels into the United States. The measure failed, but in the 1850s, then-Secretary of War Davis persuaded President Franklin Pierce that camels were the military super weapons of the future. Able to carry greater loads over longer distances than any other pack animal, Davis saw camels as the high tech weapon of the age. Hundreds of horses and mules were dying in the hot, dry conditions of Southwestern Cavalry outposts, when the government purchased 75 camels from Algeria, Tunisia and Egypt. Several camel handlers came along in the bargain, one of them a Syrian named Haji Ali, who successfully implemented a camel breeding program. Haji Ali became quite the celebrity within the West Texas outpost. The soldiers called him “Hi Jolly”.

The measure failed, but in the 1850s, then-Secretary of War Davis persuaded President Franklin Pierce that camels were the military super weapons of the future. Able to carry greater loads over longer distances than any other pack animal, Davis saw camels as the high tech weapon of the age. Hundreds of horses and mules were dying in the hot, dry conditions of Southwestern Cavalry outposts, when the government purchased 75 camels from Algeria, Tunisia and Egypt. Several camel handlers came along in the bargain, one of them a Syrian named Haji Ali, who successfully implemented a camel breeding program. Haji Ali became quite the celebrity within the West Texas outpost. The soldiers called him “Hi Jolly”.

On May 17, 1673, Father Jacques Marquette set out with the 27-year old fur trader Louis Joliet to explore the upper reaches of the Mississippi River. Their voyage established the possibility of water travel from Lake Huron to the Gulf of Mexico, helping to initiate the first white settlements in the North American interior and bestowing French names on cities from La Crosse to New Orleans.

On May 17, 1673, Father Jacques Marquette set out with the 27-year old fur trader Louis Joliet to explore the upper reaches of the Mississippi River. Their voyage established the possibility of water travel from Lake Huron to the Gulf of Mexico, helping to initiate the first white settlements in the North American interior and bestowing French names on cities from La Crosse to New Orleans.

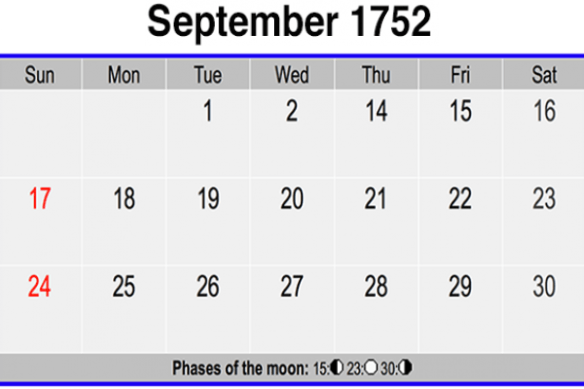

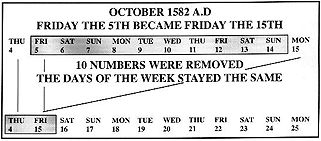

Benjamin Franklin seems to have liked the idea, writing that, “It is pleasant for an old man to be able to go to bed on September 2, and not have to get up until September 14.”

Benjamin Franklin seems to have liked the idea, writing that, “It is pleasant for an old man to be able to go to bed on September 2, and not have to get up until September 14.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.