Discussions of a road to Alaska began as early as 1865, when Western Union contemplated plans to install a telegraph wire from the United States to Siberia. The idea picked up steam with the proliferation of automobiles in the 1920s, but it was a hard sell for Canadian authorities. Such a road would necessarily pass through their territory, but the Canadian government felt the project would have little impact, benefiting no more than a few thousand people in the Yukon.

In the days following the attack on Pearl Harbor, Guam and Wake Island fell to Imperial Japanese forces , making it clear that parts of the Pacific coast were vulnerable.

Priorities were changing for both the United States and Canada.

The Alaska Territory was particularly exposed. Situated only 750 miles from the nearest Japanese base, the Aleutian Island chain had only 12 medium bombers, 20 pursuit planes, and fewer than 22,000 troops in the entire territory, an area four times the size of Texas. Colonel Simon Bolivar Buckner Jr., the officer in charge of the Alaska Defense Command, made the point succinctly. “If the Japanese come here, I can’t defend Alaska. I don’t have the resources.”

The US Army approved construction of the Alaska Highway in February, the project receiving the blessing of Congress and President Roosevelt within the week. Canada agreed to allow the project, provided that the US pay the full cost, and the roadway and other facilities be turned over to Canadian authorities at the end of the war.

Construction began in March as trains moved hundreds of pieces of construction equipment to Dawson Creek, the last stop on the Northern Alberta Railway. At the other end, 10,670 American troops arrived in Alaska that spring, to begin what their officers called “the biggest and hardest job since the Panama Canal.”

Construction began in March as trains moved hundreds of pieces of construction equipment to Dawson Creek, the last stop on the Northern Alberta Railway. At the other end, 10,670 American troops arrived in Alaska that spring, to begin what their officers called “the biggest and hardest job since the Panama Canal.”

In-between lay over 1,500 miles of unmapped, inhospitable wilderness.

The project had a new sense of urgency in June, when Japanese forces landed on Kiska and Attu Islands, in the Aleutian chain. Adding to that urgency was that there is no more than an eight month construction window, before the return of the deadly Alaskan winter.

The project had a new sense of urgency in June, when Japanese forces landed on Kiska and Attu Islands, in the Aleutian chain. Adding to that urgency was that there is no more than an eight month construction window, before the return of the deadly Alaskan winter.

Construction began at both ends and the middle at once, with nothing but the most rudimentary engineering sketches. A route through the Rockies had not even been identified yet.

Radios didn’t work across the Rockies and there was only erratic mail and passenger service on the Yukon Southern airline, a run that locals called the “Yukon Seldom”. It was faster for construction battalions at Dawson Creek, Delta Junction and Whitehorse to talk to each other through military officials in Washington, DC.

Moving men to their assigned locations was one thing, moving 11,000 pieces of construction equipment, to say nothing of the supplies needed by man and machine, was another.

Tent pegs were useless in the permafrost, while the body heat of sleeping soldiers meant they woke up in mud. Partially thawed lakes meant that supply planes could use neither pontoon nor ski, as Black flies swarmed the troops by day, and bears raided camps at night, looking for food.

Engines had to run around the clock, as it was impossible to restart them in the cold. Engineers waded up to their chests building pontoons across freezing lakes, battling mosquitoes in the mud and the moss laden arctic bog. Ground that had been frozen for thousands of years was scraped bare and exposed to sunlight, creating a deadly layer of muddy quicksand in which bulldozers sank in what seemed like stable roadbed.

Engines had to run around the clock, as it was impossible to restart them in the cold. Engineers waded up to their chests building pontoons across freezing lakes, battling mosquitoes in the mud and the moss laden arctic bog. Ground that had been frozen for thousands of years was scraped bare and exposed to sunlight, creating a deadly layer of muddy quicksand in which bulldozers sank in what seemed like stable roadbed.

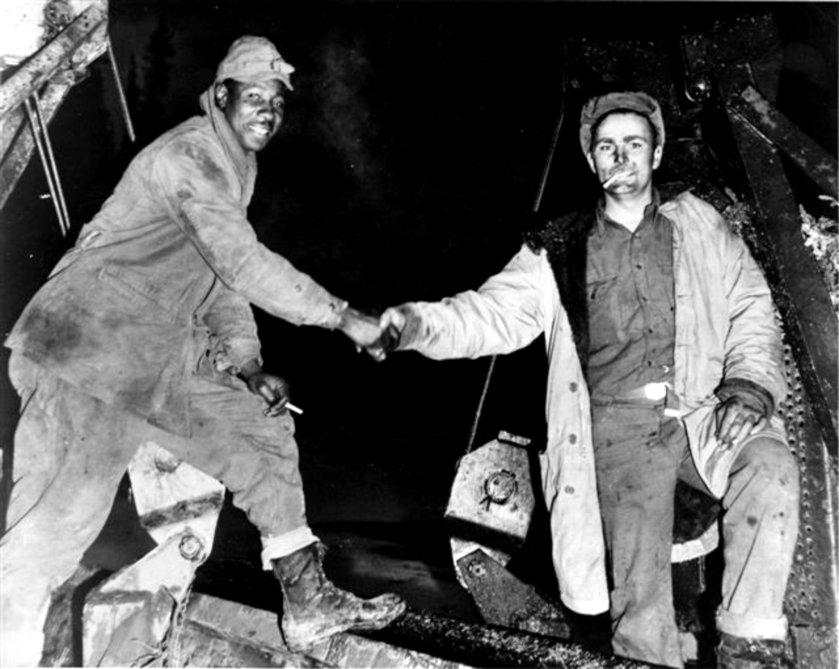

On October 25, Refines Sims Jr. of Philadelphia, with the all-black 97th Engineers was driving a bulldozer 20 miles east of the Alaska-Yukon line, when the trees in front of him toppled to the ground. He slammed his machine into reverse as a second bulldozer came into view, driven by Kennedy, Texas Private Alfred Jalufka. North had met south, and the two men jumped off their machines, grinning. Their triumphant handshake was photographed by a fellow soldier and published in newspapers across the country, becoming an unintended first step toward desegregating the US military.

They celebrated the route’s completion at Soldier’s Summit on November 21, 1942, though the “highway” remained unusable by most vehicles, until 1943.

NPR ran an interview about this story back in the eighties, in which an Inupiaq elder was recounting his memories. He had grown up in a world as it existed for hundreds of years, without so much as an idea of internal combustion. He spoke of the day that he first heard the sound of an engine, and went out to see a giant bulldozer making its way over the permafrost. The bulldozer was being driven by a black operator, probably one of the 97th Engineers Battalion soldiers. I thought the old man’s comment was a classic. “It turned out”, he said, “that the first white person I ever saw, was a black man”.

This was a time of big hair, when hair was piled high on top of the head, powdered, and augmented with the hair of servants and pets. The do was often adorned with fabric, ribbons or fruit, sometimes holding props like birdcages complete with stuffed birds, and even miniature frigates, under sail.

This was a time of big hair, when hair was piled high on top of the head, powdered, and augmented with the hair of servants and pets. The do was often adorned with fabric, ribbons or fruit, sometimes holding props like birdcages complete with stuffed birds, and even miniature frigates, under sail.

“Mainstream” white artists of the fifties and sixties often covered songs written by black artists. On April 6, 1963, an obscure rock & roll group out of Portland, Oregon covered the song, renting a recording studio for $50. They were The Kingsmen.

“Mainstream” white artists of the fifties and sixties often covered songs written by black artists. On April 6, 1963, an obscure rock & roll group out of Portland, Oregon covered the song, renting a recording studio for $50. They were The Kingsmen.

Strangely, the feds never interviewed Kingsmen lead singer Jack Ely, who probably could have saved them a lot of time.

Strangely, the feds never interviewed Kingsmen lead singer Jack Ely, who probably could have saved them a lot of time.

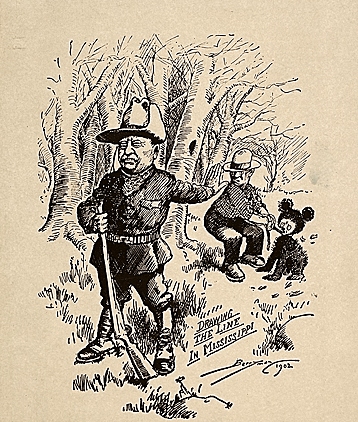

Roosevelt declined to shoot the animal, calling it “unsportsmanlike” to shoot a bound and wounded animal. Instead, he ordered the bear put down, putting an end to its pain.

Roosevelt declined to shoot the animal, calling it “unsportsmanlike” to shoot a bound and wounded animal. Instead, he ordered the bear put down, putting an end to its pain.

Officials discussed the matter with the Navy (it wasn’t every day that they had to remove 16,000 lbs of rotting whale meat) and someone came up with a bright idea. They would remove the carcass the same way they’d remove a huge boulder. They’d blow it up.

Officials discussed the matter with the Navy (it wasn’t every day that they had to remove 16,000 lbs of rotting whale meat) and someone came up with a bright idea. They would remove the carcass the same way they’d remove a huge boulder. They’d blow it up. The detonation tore through the whale, like a bullet passes through a pane of glass. Thousands of chunks of dead whale, large and small, soared through the air, landing on nearby buildings, houses and streets.

The detonation tore through the whale, like a bullet passes through a pane of glass. Thousands of chunks of dead whale, large and small, soared through the air, landing on nearby buildings, houses and streets.

Born on October 29, 1921 in New Mexico and brought up in Arizona, William Henry “Bill” Mauldin was part of what Tom Brokaw called, the “Greatest Generation”.

Born on October 29, 1921 in New Mexico and brought up in Arizona, William Henry “Bill” Mauldin was part of what Tom Brokaw called, the “Greatest Generation”. Mauldin developed two cartoon infantrymen, calling them “Willie and Joe”. He told the story of the war through their eyes. He became extremely popular within the enlisted ranks, while his humor tended to poke fun at the “spit & polish” of the officer corps. He even lampooned General George Patton one time, for insisting that his men to be clean shaven all the time. Even in combat.

Mauldin developed two cartoon infantrymen, calling them “Willie and Joe”. He told the story of the war through their eyes. He became extremely popular within the enlisted ranks, while his humor tended to poke fun at the “spit & polish” of the officer corps. He even lampooned General George Patton one time, for insisting that his men to be clean shaven all the time. Even in combat. Mauldin later told an interviewer, “I always admired Patton. Oh, sure, the stupid bastard was crazy. He was insane. He thought he was living in the Dark Ages. Soldiers were peasants to him. I didn’t like that attitude, but I certainly respected his theories and the techniques he used to get his men out of their foxholes”.

Mauldin later told an interviewer, “I always admired Patton. Oh, sure, the stupid bastard was crazy. He was insane. He thought he was living in the Dark Ages. Soldiers were peasants to him. I didn’t like that attitude, but I certainly respected his theories and the techniques he used to get his men out of their foxholes”. Bill Mauldin drew Willie & Joe for last time in 1998, for inclusion in Schulz’ Veteran’s Day Peanuts strip. Schulz had long described Mauldin as his hero. He signed that final strip Schulz, as always, and added “and my Hero“. Bill Mauldin’s signature, appears underneath.

Bill Mauldin drew Willie & Joe for last time in 1998, for inclusion in Schulz’ Veteran’s Day Peanuts strip. Schulz had long described Mauldin as his hero. He signed that final strip Schulz, as always, and added “and my Hero“. Bill Mauldin’s signature, appears underneath.

In New York city and “upstate” alike, economic ties with the south ran deep. 40¢ of every dollar paid for southern cotton stayed in New York, in the form of insurance, shipping, warehouse fees and profits.

In New York city and “upstate” alike, economic ties with the south ran deep. 40¢ of every dollar paid for southern cotton stayed in New York, in the form of insurance, shipping, warehouse fees and profits. “Town Line”, a hamlet on the village’s eastern boundary, put it to a vote. In the fall of 1861, residents gathered in the old schoolhouse-turned blacksmith’s shop. By a margin of 85 to 40, Town Line, New York voted to secede from the Union.

“Town Line”, a hamlet on the village’s eastern boundary, put it to a vote. In the fall of 1861, residents gathered in the old schoolhouse-turned blacksmith’s shop. By a margin of 85 to 40, Town Line, New York voted to secede from the Union. A rumor went around in 1864, that a

A rumor went around in 1864, that a  Even Georgians couldn’t help themselves from commenting. 97-year-old Confederate General T.W. Dowling said: “We been rather pleased with the results since we rejoined the Union. Town Line ought to give the United States another try“. Judge A.L. Townsend of Trenton Georgia commented “Town Line ought to give the United States a good second chance“.

Even Georgians couldn’t help themselves from commenting. 97-year-old Confederate General T.W. Dowling said: “We been rather pleased with the results since we rejoined the Union. Town Line ought to give the United States another try“. Judge A.L. Townsend of Trenton Georgia commented “Town Line ought to give the United States a good second chance“. Fireman’s Hall became the site of the barbecue, “The old blacksmith shop where the ruckus started” being too small for the assembled crowd. On October 28, 1945, residents adopted a resolution suspending its 1861 ordinance of secession, by a vote of 90-23. The Stars and Bars of the Lost Cause was lowered for the last time, outside the old blacksmith shop.

Fireman’s Hall became the site of the barbecue, “The old blacksmith shop where the ruckus started” being too small for the assembled crowd. On October 28, 1945, residents adopted a resolution suspending its 1861 ordinance of secession, by a vote of 90-23. The Stars and Bars of the Lost Cause was lowered for the last time, outside the old blacksmith shop.

This is a story of Independence, of Revolution. Of overthrowing a Spanish-speaking government, and creating an Independent Republic in the American South. Its banner was a single, five-pointed white star on a blue field. It was the original Lone Star Republic. The Republic of West Florida.

This is a story of Independence, of Revolution. Of overthrowing a Spanish-speaking government, and creating an Independent Republic in the American South. Its banner was a single, five-pointed white star on a blue field. It was the original Lone Star Republic. The Republic of West Florida. The French first came to America in 1524, colonizing vast expanses from Quebec to Green Bay in the north, Baton Rouge to Biloxi in the south. They sought wealth, territory and a route to the Pacific Ocean. What they got was endless conflict.

The French first came to America in 1524, colonizing vast expanses from Quebec to Green Bay in the north, Baton Rouge to Biloxi in the south. They sought wealth, territory and a route to the Pacific Ocean. What they got was endless conflict. President Jefferson bought 828,000 square miles from the French in 1803, doubling the size of the United States, but the exact borders were unclear.

President Jefferson bought 828,000 square miles from the French in 1803, doubling the size of the United States, but the exact borders were unclear. That was about it. Surviving soldados fled, as the flag of the new Republic was unfurled over the fort: a dark blue field with a single white star. The whole thing had taken about a minute.

That was about it. Surviving soldados fled, as the flag of the new Republic was unfurled over the fort: a dark blue field with a single white star. The whole thing had taken about a minute.

In April 1864, President Jefferson Davis dispatched former Secretary of the Interior Jacob Thompson, ex-Alabama Senator Clement Clay, and veteran Confederate spy Captain Thomas Henry Hines to Toronto, with the mission of raising hell in the North.

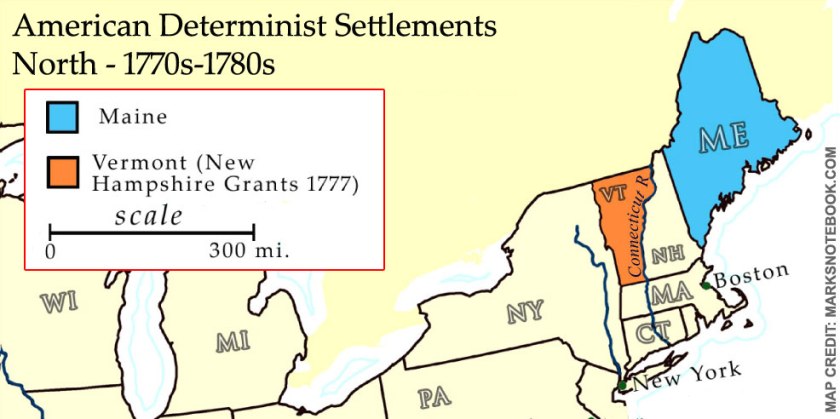

In April 1864, President Jefferson Davis dispatched former Secretary of the Interior Jacob Thompson, ex-Alabama Senator Clement Clay, and veteran Confederate spy Captain Thomas Henry Hines to Toronto, with the mission of raising hell in the North. The Confederate invasion of Maine never materialized, thanks in large measure to counter-espionage efforts by Union agents.

The Confederate invasion of Maine never materialized, thanks in large measure to counter-espionage efforts by Union agents.

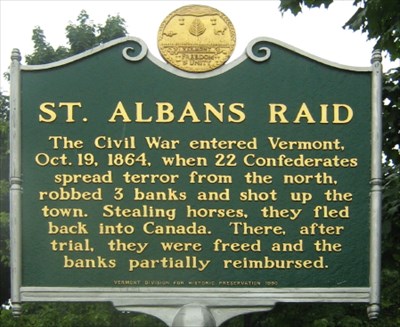

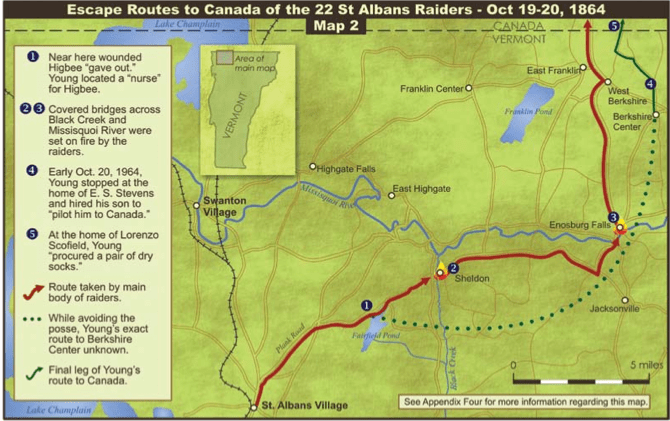

The group was arrested on returning to Canada and held in Montreal. The Lincoln administration sought extradition, but the Canadian court decided otherwise, ruling that the raiders were under military orders at the time, and neutral Canada could not extradite them to America. The $88,000 found with the raiders, was returned to Vermont.

The group was arrested on returning to Canada and held in Montreal. The Lincoln administration sought extradition, but the Canadian court decided otherwise, ruling that the raiders were under military orders at the time, and neutral Canada could not extradite them to America. The $88,000 found with the raiders, was returned to Vermont.

The Meux’s Brewery Co Ltd, established in 1764, was a London brewery owned by Sir Henry Meux. What the Times article was describing was a 22′ high monstrosity, held together by 29 iron hoops.

The Meux’s Brewery Co Ltd, established in 1764, was a London brewery owned by Sir Henry Meux. What the Times article was describing was a 22′ high monstrosity, held together by 29 iron hoops.

323,000 imperial gallons of beer smashed through the brewery’s 25′ high brick walls, gushing into the streets, homes and businesses of St. Giles. The torrent smashed two houses and the nearby Tavistock Arms pub on Great Russell Street, where a 14-year-old barmaid named Eleanor Cooper was buried under the rubble.

323,000 imperial gallons of beer smashed through the brewery’s 25′ high brick walls, gushing into the streets, homes and businesses of St. Giles. The torrent smashed two houses and the nearby Tavistock Arms pub on Great Russell Street, where a 14-year-old barmaid named Eleanor Cooper was buried under the rubble. In the days that followed, the crushing poverty of the slum led some to exhibit the corpses of their family members, charging a fee for anyone who wanted to come in and see. In one house, too many people crowded in and the floor collapsed, plunging them all into a cellar full of beer.

In the days that followed, the crushing poverty of the slum led some to exhibit the corpses of their family members, charging a fee for anyone who wanted to come in and see. In one house, too many people crowded in and the floor collapsed, plunging them all into a cellar full of beer.

You must be logged in to post a comment.