On September 13, 1987, Roberto dos Santos Alves and Wagner Mota Pereira entered the Instituto Goiano de Radioterapia (IGR), bent on theft. The private hospital was permanently closed at the time, and partly demolished. Alves and Pereira were looking for anything they might sell, for scrap.

On September 13, 1987, Roberto dos Santos Alves and Wagner Mota Pereira entered the Instituto Goiano de Radioterapia (IGR), bent on theft. The private hospital was permanently closed at the time, and partly demolished. Alves and Pereira were looking for anything they might sell, for scrap.

What they found, was more than either man had bargained for.

At one time, the radiotherapy unit in the central Brazilian city of Goiânia had served untold numbers of oncology patients, using ionizing radiation to control cell growth and even kill off any number of cancers, following surgical removal of the tumor.

Now, the abandoned machine was little more than a radiological time bomb.

Four months earlier, the IGR had attempted to remove their equipment, in the midst of a legal dispute with then-owner of the property, the Society of Saint Vincent de Paul. A court order prevented the removal, as owners of the company wrote letters to the National Nuclear Energy Commission, warning that someone needed to take responsibility “for what would happen with the caesium bomb”.

The radioactive source within the “external beam radio therapy” unit is a “wheel type” canister, with shielding walls of lead and steel and designed to rotate the source material when in use, between storage and irradiation positions.

Alves and Pereira removed the capsule from the heart of the machine, the stainless steel canister containing just over 3-ounces of highly radioactive caesium chloride, an inorganic salt derived from the radioisotope, caesium-137.

The court had posted a security guard, but he or she must have been snoozing, at the time. The two scavengers placed the canister in a wheel barrow, and brought it to Alves’ home to see what they had found.

The pair experienced the dizziness and diarrhea of radiation poisoning, but attributed symptoms to something they ate. Pereira developed burns on his fingers, the size and shape of the canister’s aperture. Meanwhile, Alves continued to tinker with the thing, finally freeing the capsule from its protective rotating head. Poking the capsule with a screwdriver, a dark blue light could be seen from within, the florescence of electromagnetic radiation.

Radiation burns would cost Pereira his fingers and Alves his right arm, but the two would survive the exposure. The owner of the scrapyard they sold the thing to, wasn’t so lucky.

Five days after the theft, Alves sold the items he had pilfered, to a nearby scrapyard. Noticing the blue glow from the punctured capsule, the scrapyard owner thought the object might be valuable or even supernatural, and took the thing inside. Several rice-sized grains of the glowing material were pried from inside the capsule, as Devair Ferreira (the owner of the scrapyard) invited friends and family to come and see the strange, glowing substance. Ferreira’s brother Ivo brought some of the stuff home to his six-year-old daughter, about the time when Devair’s 37-year-old wife Gabriela, became ill.

Five days after the theft, Alves sold the items he had pilfered, to a nearby scrapyard. Noticing the blue glow from the punctured capsule, the scrapyard owner thought the object might be valuable or even supernatural, and took the thing inside. Several rice-sized grains of the glowing material were pried from inside the capsule, as Devair Ferreira (the owner of the scrapyard) invited friends and family to come and see the strange, glowing substance. Ferreira’s brother Ivo brought some of the stuff home to his six-year-old daughter, about the time when Devair’s 37-year-old wife Gabriela, became ill.

It was she who first noticed how many and how quickly, the people around her were getting sick. Too late for Ivo’s daughter Leide, who couldn’t resist rubbing the glowing blue powder on her skin, and showing it to her mother. Anyone who ever raised a six-year-old daughter, knows what that must have looked like.

By the time the presence of nuclear radiation was discovered on the 29th, the Goiânia nuclear disaster qualified as a Five on the International Scale of Nuclear Events, the INES. Tons of topsoil had to be removed from a number of sites, and several houses, demolished.

The incident was broadcast all over Brazil, and 130,000 people people flooded into area hospitals, afraid they had been exposed. One thousand individuals showed greater than background levels of radiation, 249 showed significant signs of contamination.

The incident was broadcast all over Brazil, and 130,000 people people flooded into area hospitals, afraid they had been exposed. One thousand individuals showed greater than background levels of radiation, 249 showed significant signs of contamination.

Four died. The wife of the scrapyard owner Gabriela, who was first to figure it all out. Two employees who had worked to remove the lead for its scrap value, Israel dos Santos aged 22 and Admilson de Souza, aged 18. And that little girl, Leide, who was so happy to see her skin, glowing blue.

In the public civil suit that followed, the three doctors who owned the IGR, were ordered to pay 100,000 Brazilian Real, (equivalent to $24,000 US), for the derelict condition of the building. The two thieves who stole the stuff in the first place, were never charged.

If you enjoyed this “Today in History”, please feel free to re-blog, “like” & share on social media, so that others may find and enjoy it as well. Please click the “follow” button on the right, to receive email updates on new articles. Thank you for your interest, in the history we all share.

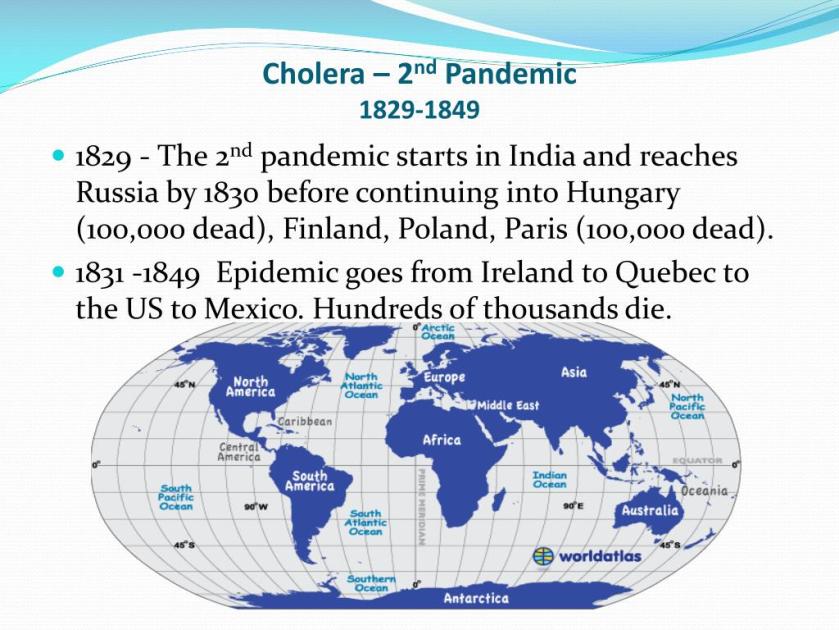

The world would see four more cholera pandemics between 1852 and 1923, with the first being by far, the deadliest. This one devastated much of Asia, North America and Africa. in 1854, the worst year of the outbreak, 23,000 died in Great Britain, alone.

The world would see four more cholera pandemics between 1852 and 1923, with the first being by far, the deadliest. This one devastated much of Asia, North America and Africa. in 1854, the worst year of the outbreak, 23,000 died in Great Britain, alone.

Several other outbreaks had occurred that year, but this one was particularly acute. Within the next three days, 127 died within a short distance of the Broad Street address. By September 10, there were five-hundred more.

Several other outbreaks had occurred that year, but this one was particularly acute. Within the next three days, 127 died within a short distance of the Broad Street address. By September 10, there were five-hundred more.

Gehrig was pitching for Columbia University against Williams College on April 18, 1923, the day that Babe Ruth hit the first home run out of the brand new Yankee Stadium. Though Columbia would lose the game, Gehrig struck out seventeen batters that day, to set a team record. The loss didn’t matter to Paul Krichell, the Yankee scout who had been following Gehrig. Krichell didn’t care about the arm either, as much as he did that powerful, left-handed bat. He had seen Gehrig hit some of the longest home runs ever seen on several Eastern campuses, including a 450′ home run at Columbia’s South Field that cleared the stands and landed at 116th Street and Broadway.

Gehrig was pitching for Columbia University against Williams College on April 18, 1923, the day that Babe Ruth hit the first home run out of the brand new Yankee Stadium. Though Columbia would lose the game, Gehrig struck out seventeen batters that day, to set a team record. The loss didn’t matter to Paul Krichell, the Yankee scout who had been following Gehrig. Krichell didn’t care about the arm either, as much as he did that powerful, left-handed bat. He had seen Gehrig hit some of the longest home runs ever seen on several Eastern campuses, including a 450′ home run at Columbia’s South Field that cleared the stands and landed at 116th Street and Broadway.

The team was in Detroit on May 2 when he told manager Joe McCarthy “I’m benching myself, Joe”. It’s “for the good of the team”. McCarthy put Babe Dahlgren in at first and the Yankees won 22-2, but that was it. The Iron Horse’s streak of 2,130 consecutive games, had come to an end.

The team was in Detroit on May 2 when he told manager Joe McCarthy “I’m benching myself, Joe”. It’s “for the good of the team”. McCarthy put Babe Dahlgren in at first and the Yankees won 22-2, but that was it. The Iron Horse’s streak of 2,130 consecutive games, had come to an end. Gehrig left the team in June, arriving at the Mayo Clinic on the 13th. The diagnosis of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) was confirmed six days later, on June 19. It was his 36th birthday. It was a cruel prognosis: rapidly increasing paralysis, difficulty in swallowing and speaking, and a life expectancy of fewer than three years.

Gehrig left the team in June, arriving at the Mayo Clinic on the 13th. The diagnosis of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) was confirmed six days later, on June 19. It was his 36th birthday. It was a cruel prognosis: rapidly increasing paralysis, difficulty in swallowing and speaking, and a life expectancy of fewer than three years.

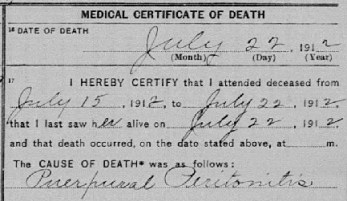

In the mid-19th century, birthing centers were set up all over Europe, for the care of poor and underprivileged mothers and their illegitimate infants. Care was provided free of charge, in exchange for which young mothers agreed to become training subjects for doctors and midwives.

In the mid-19th century, birthing centers were set up all over Europe, for the care of poor and underprivileged mothers and their illegitimate infants. Care was provided free of charge, in exchange for which young mothers agreed to become training subjects for doctors and midwives. At the time, Vienna General Hospital ran two such clinics, the 1st a “teaching hospital” for undergraduate medical students, the 2nd for student midwives.

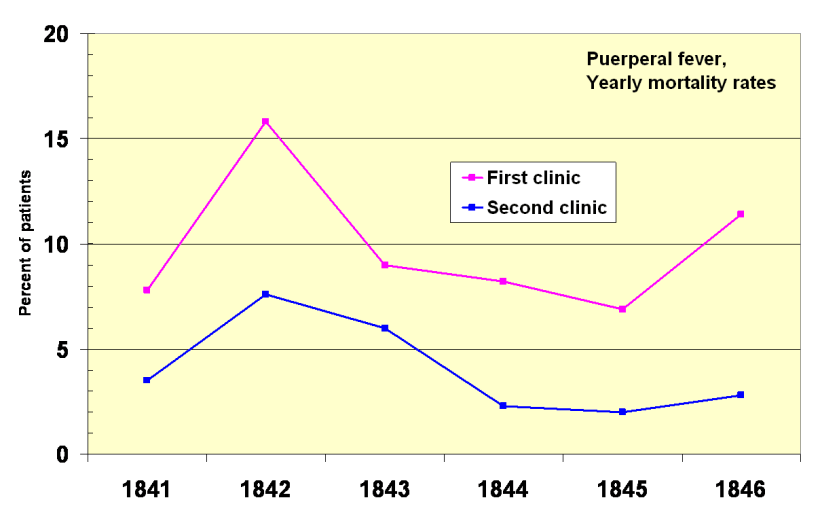

At the time, Vienna General Hospital ran two such clinics, the 1st a “teaching hospital” for undergraduate medical students, the 2nd for student midwives. Childbed or “puerperal” fever was rare among these “street births”, and far more prevalent in the First Clinic, than the Second. Semmelweis carefully eliminated every difference between the two, even including religious practices. In the end, the only difference was the people who worked there.

Childbed or “puerperal” fever was rare among these “street births”, and far more prevalent in the First Clinic, than the Second. Semmelweis carefully eliminated every difference between the two, even including religious practices. In the end, the only difference was the people who worked there. Mortality rates in the First Clinic dropped by 90%, to rates comparable with the Second. In April 1847, First Clinic mortality rates were 18.3% – nearly one in five. Hand washing was instituted in mid-May, and June rates dropped to 2.2%. July was 1.2%. For two months, the rate was zero.

Mortality rates in the First Clinic dropped by 90%, to rates comparable with the Second. In April 1847, First Clinic mortality rates were 18.3% – nearly one in five. Hand washing was instituted in mid-May, and June rates dropped to 2.2%. July was 1.2%. For two months, the rate was zero. Dr. Semmelweis was outraged by the indifference of the medical community, and began to write open and increasingly angry letters to prominent European obstetricians. He went so far as to denounce such people as “irresponsible murderers”, leading contemporaries and even his wife, to doubt his mental stability.

Dr. Semmelweis was outraged by the indifference of the medical community, and began to write open and increasingly angry letters to prominent European obstetricians. He went so far as to denounce such people as “irresponsible murderers”, leading contemporaries and even his wife, to doubt his mental stability.

Most such outbreaks coincided with periods of extreme hardship such as crop failure, famine and floods, and involved between dozens and tens of thousands of individuals.

Most such outbreaks coincided with periods of extreme hardship such as crop failure, famine and floods, and involved between dozens and tens of thousands of individuals. Even today there is little consensus about what caused the phenomenon. Some have blamed “St Anthony’s Fire”, a toxic and psychoactive fungus of the Claviceps genus, also known as ergot. Often ingested with infected rye bread, symptoms of ergot poisoning are not unlike those of LSD, and include nervous spasms, psychotic delusions, spontaneous abortion, convulsions and gangrene resulting from severe vasoconstriction.

Even today there is little consensus about what caused the phenomenon. Some have blamed “St Anthony’s Fire”, a toxic and psychoactive fungus of the Claviceps genus, also known as ergot. Often ingested with infected rye bread, symptoms of ergot poisoning are not unlike those of LSD, and include nervous spasms, psychotic delusions, spontaneous abortion, convulsions and gangrene resulting from severe vasoconstriction.

Gehrig was pitching for Columbia University against Williams College on April 18, 1923, the day that Babe Ruth hit the first home run out of the brand new Yankee Stadium. Though Columbia would lose the game, Gehrig struck out seventeen batters to set a team record.

Gehrig was pitching for Columbia University against Williams College on April 18, 1923, the day that Babe Ruth hit the first home run out of the brand new Yankee Stadium. Though Columbia would lose the game, Gehrig struck out seventeen batters to set a team record.

Lou Gehrig collapsed in 1939 spring training, going into an abrupt decline early in the season. The Yankees were in Detroit on May 2 when Gehrig told manager Joe McCarthy “I’m benching myself, Joe”. It’s “for the good of the team”. McCarthy put Babe Dahlgren in at first and the Yankees won 22-2, but that was it. The Iron Horse’s streak of 2,130 consecutive games, had come to an end.

Lou Gehrig collapsed in 1939 spring training, going into an abrupt decline early in the season. The Yankees were in Detroit on May 2 when Gehrig told manager Joe McCarthy “I’m benching myself, Joe”. It’s “for the good of the team”. McCarthy put Babe Dahlgren in at first and the Yankees won 22-2, but that was it. The Iron Horse’s streak of 2,130 consecutive games, had come to an end.

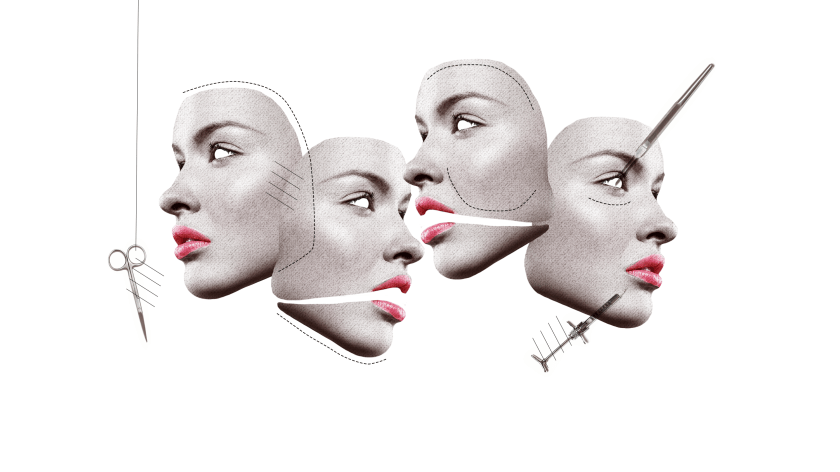

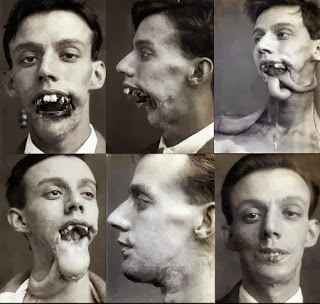

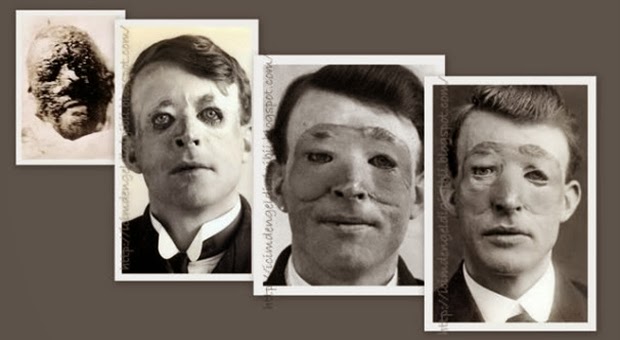

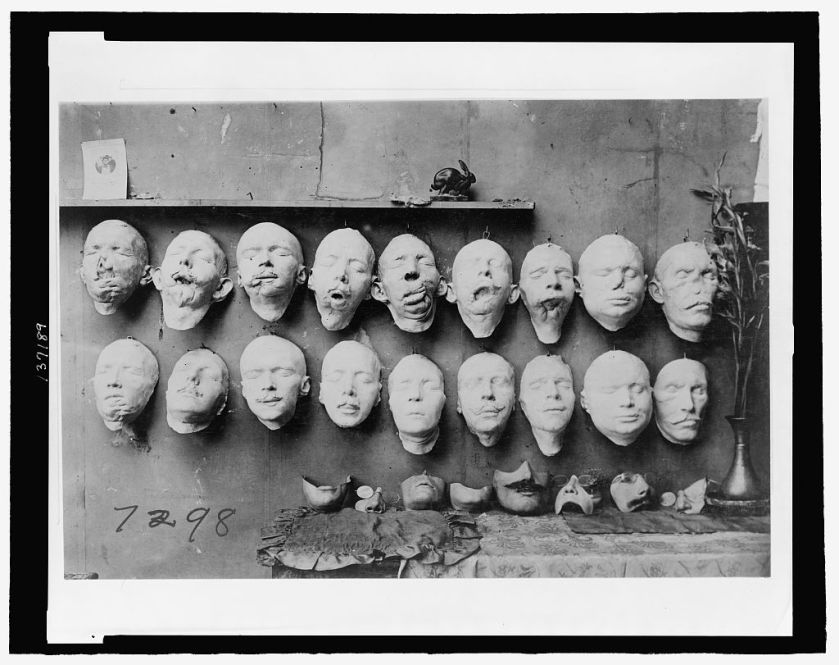

“Plastic” Surgery, the term comes to us from the Greek Plastikos and first used by the 18th century French surgeon Pierre Desault, has been with us longer than you might expect. Evidence exists of Hindu surgeons performing primitive ‘nose jobs’, as early as BC800-600. The Renaissance-era surgeon Gaspare Tagliacozzi (1545-1599) developed new methods of reconstruction, using the patient’s own arm skin to replace noses slashed off in swordplay.

“Plastic” Surgery, the term comes to us from the Greek Plastikos and first used by the 18th century French surgeon Pierre Desault, has been with us longer than you might expect. Evidence exists of Hindu surgeons performing primitive ‘nose jobs’, as early as BC800-600. The Renaissance-era surgeon Gaspare Tagliacozzi (1545-1599) developed new methods of reconstruction, using the patient’s own arm skin to replace noses slashed off in swordplay.

Ladd’s prostheses were uncomfortable to wear, but her services earned her the Légion d’Honneur Croix de Chevalier and the Serbian Order of Saint Sava.

Ladd’s prostheses were uncomfortable to wear, but her services earned her the Légion d’Honneur Croix de Chevalier and the Serbian Order of Saint Sava.

Dr. Gillies & Co. developed surgical methods in which rib cartilage is first implanted in foreheads, and then swung down to form the foundational structure of a new nose.

Dr. Gillies & Co. developed surgical methods in which rib cartilage is first implanted in foreheads, and then swung down to form the foundational structure of a new nose.

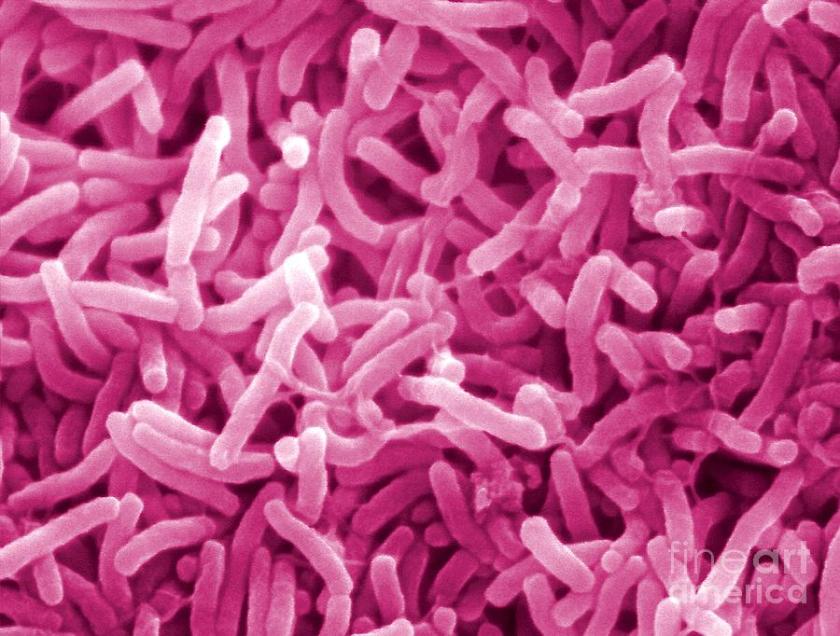

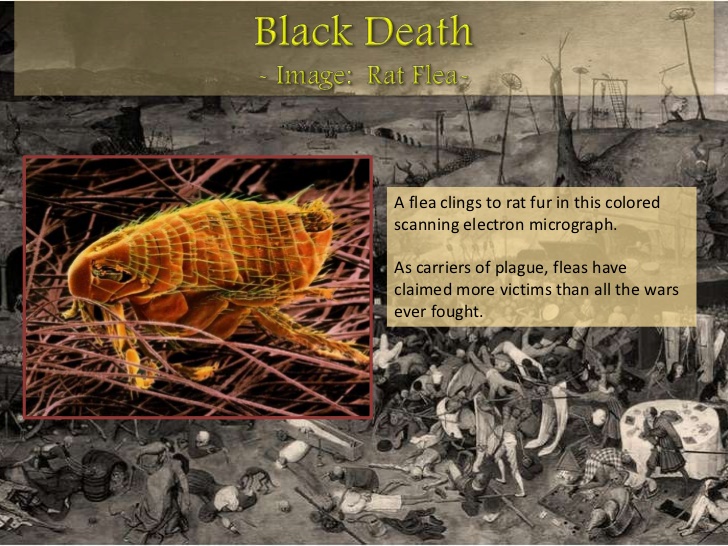

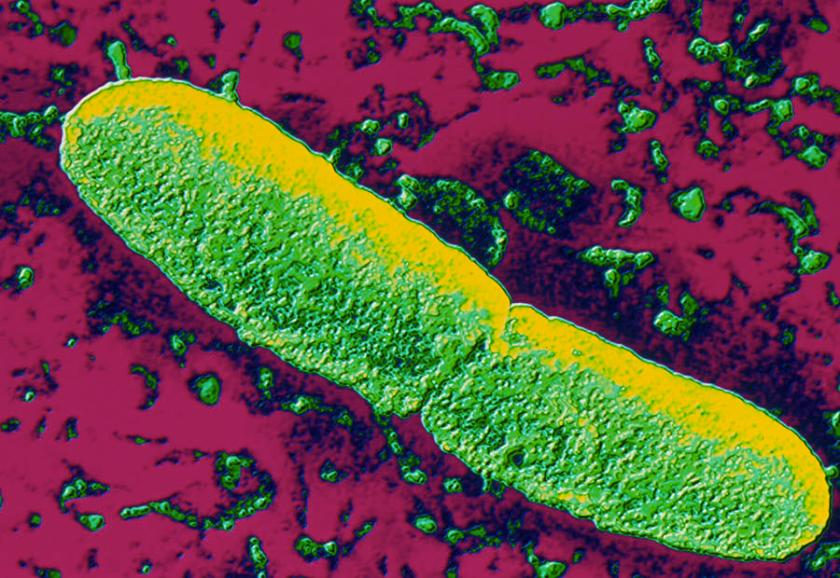

In the early 1330s, a deadly plague broke out on the steppes of Mongolia. The gram-negative bacterium Yersinia Pestis preyed heavily on rodents, the fleas from which would transmit the disease to people, the infection then rapidly spreading to others.

In the early 1330s, a deadly plague broke out on the steppes of Mongolia. The gram-negative bacterium Yersinia Pestis preyed heavily on rodents, the fleas from which would transmit the disease to people, the infection then rapidly spreading to others.

The Black death of 1346-’53 was a catastrophe unparalleled in human history, but it was by no means the last such outbreak. The Third Pandemic began in China in 1855, spreading to Hong Kong and on to British India. In China and India alone the disease killed 12 million people. It then spread to parts of Africa, Europe, Australia, and South America.

The Black death of 1346-’53 was a catastrophe unparalleled in human history, but it was by no means the last such outbreak. The Third Pandemic began in China in 1855, spreading to Hong Kong and on to British India. In China and India alone the disease killed 12 million people. It then spread to parts of Africa, Europe, Australia, and South America.

The body of an elderly Chinese man was discovered in a Chinatown basement. An autopsy found the man to have died of plague. There were more than 18,000 Chinese and another 2,000 Japanese living in the 14-block Chinatown section of the city. Many called for a quarantine of Chinatown, but Chinese citizens objected, as did then-Governor Henry Gage, who tried to sweep the whole outbreak under the carpet. Business interests likewise objected to the quarantine. Except for the Hearst Newspapers, not much was heard about it.

The body of an elderly Chinese man was discovered in a Chinatown basement. An autopsy found the man to have died of plague. There were more than 18,000 Chinese and another 2,000 Japanese living in the 14-block Chinatown section of the city. Many called for a quarantine of Chinatown, but Chinese citizens objected, as did then-Governor Henry Gage, who tried to sweep the whole outbreak under the carpet. Business interests likewise objected to the quarantine. Except for the Hearst Newspapers, not much was heard about it. San Francisco was hit by a massive earthquake on April 18, 1906, followed by a great fire. Thousands of San Franciscans were crowded into refugee camps with an even higher number of rats. For the first time, the disease now jumped the boundaries of Chinatown.

San Francisco was hit by a massive earthquake on April 18, 1906, followed by a great fire. Thousands of San Franciscans were crowded into refugee camps with an even higher number of rats. For the first time, the disease now jumped the boundaries of Chinatown.

Édouard Séguin, the Paris-born physician and educator best known for his work with the developmentally disabled and a major inspiration to Italian educator Maria Montessori, called the elder Bell’s work “…a greater invention than the telephone by his son, Alexander Graham Bell”.

Édouard Séguin, the Paris-born physician and educator best known for his work with the developmentally disabled and a major inspiration to Italian educator Maria Montessori, called the elder Bell’s work “…a greater invention than the telephone by his son, Alexander Graham Bell”. It was Alexander Graham Bell who first broke through to Helen Keller, a year before Anne Sullivan. The two developed a life-long relationship closely resembling that of father and daughter. Bell made it possible for Keller to attend Radcliffe and graduate in 1904, the first deaf/blind person, ever to do so.

It was Alexander Graham Bell who first broke through to Helen Keller, a year before Anne Sullivan. The two developed a life-long relationship closely resembling that of father and daughter. Bell made it possible for Keller to attend Radcliffe and graduate in 1904, the first deaf/blind person, ever to do so.

In September 1881, Alexander Graham Bell hurriedly invented the first metal detector, as President James Garfield lay dying from an assassin’s bullet. The device was unsuccessful in saving the President, but credited with saving many lives during the Boer War and WW1.

In September 1881, Alexander Graham Bell hurriedly invented the first metal detector, as President James Garfield lay dying from an assassin’s bullet. The device was unsuccessful in saving the President, but credited with saving many lives during the Boer War and WW1.

You must be logged in to post a comment.