In the 12th century, French philosopher Bernard of Chartres talked about the concept of “discovering truth by building on previous discoveries”. The idea is familiar to the reader of English as expressed by the mathematician and astronomer Isaac Newton, who observed that “If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants.”

Nowhere is there more truth to the old adage, than in the world of medicine. In 1841, the child who survived to celebrate a fifth birthday could look forward to a life of some 55 years. Today, a five-year-old can expect to live to eighty-two, fully half again that of the earlier date.

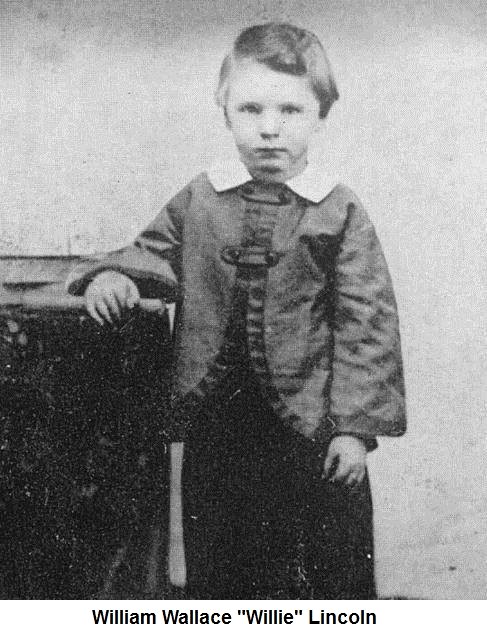

Yet, there are times when the giants who brought us here are unknown to us, as if they had never been. One such is Dr. Ignaz Semmelweis, one of the earliest pioneers in anti-septic medicine.

In the third century AD, the Greek physician Galen of Pergamon first described the “miasma” theory of illness, holding that infectious diseases such as cholera, chlamydia and the Black Death were caused by noxious clouds of “bad air”. The theory is discredited today, but such ideas die hard.

The germ theory of disease was first proposed by Girolamo Fracastoro in 1546 and expanded by Marcus von Plenciz in 1762. Single-cell organisms – bacteria – were known to exist in human dental plaque as early as 1683, yet their functions were imperfectly understood. Today, the idea that microorganisms such as fungi, viruses and other pathogens cause infectious disease is common knowledge, but such ideas were held in disdain among scientists and doctors, well into the 19th century.

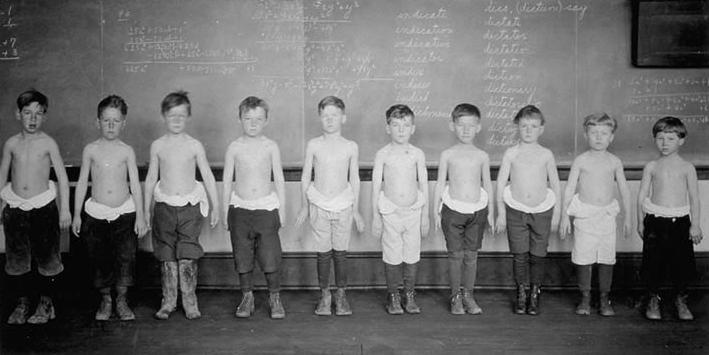

In the mid-19th century, birthing centers were set up all over Europe, for the care of poor and underprivileged mothers and their illegitimate infants. Care was provided free of charge, in exchange for which young mothers agreed to become training subjects for doctors and midwives.

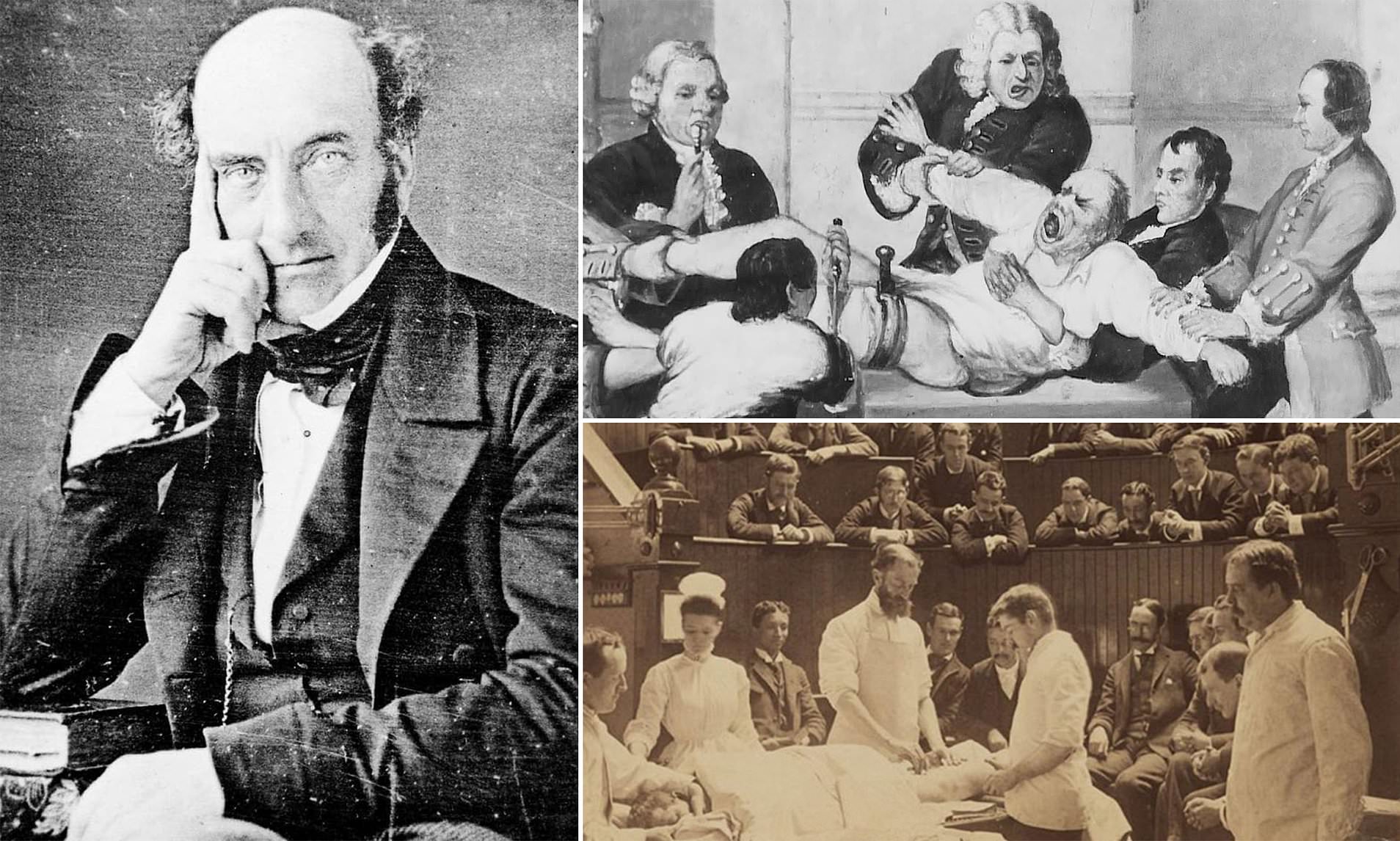

In 1846, Semmelweis was appointed assistant to Professor Johann Klein in the First Obstetrical Clinic of the Vienna General Hospital, a position similar to a “chief resident,” of today.

At the time, Vienna General Hospital ran two such clinics, the 1st a “teaching hospital” for undergraduate medical students, the 2nd for student midwives.

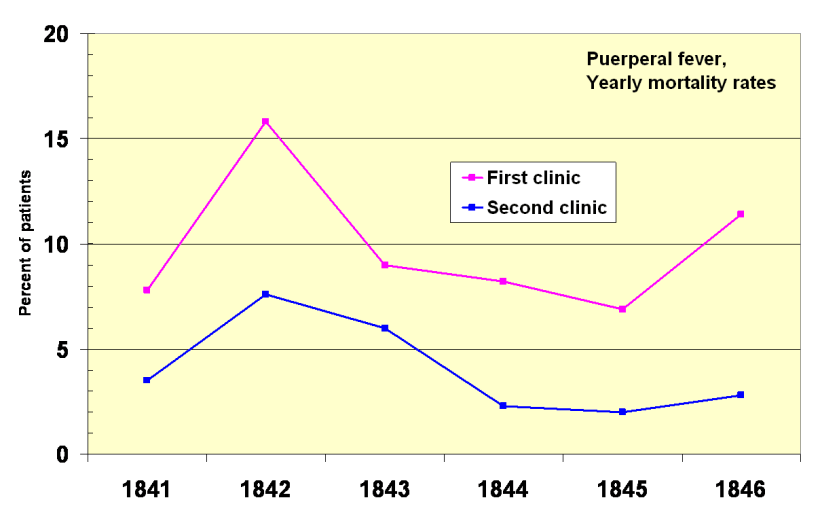

Semmelweis quickly noticed that one in ten women and sometimes one in five, were dying in the First Clinic of postpartum infection known as “childbed fever”, compared with less than 4% that of the Second Clinic.

The difference was well known, even outside of the hospital. Expectant mothers were admitted on alternate days into the First or Second Clinic. Desperate women begged on their knees not to be admitted into the First, some preferring even to give birth in the streets, over delivery in that place. The disparity between the two clinics “made me so miserable”, Semmelweis said, “that life seemed worthless”.

He had to know why this was happening.

Childbed or “puerperal” fever was rare among these “street births”, and far more prevalent in the First Clinic, than the Second. Semmelweis carefully eliminated every difference between the two, even including religious practices. In the end, the only difference was the people who worked there.

The breakthrough came in 1847, following the death of Semmelweis’ friend and colleague, Dr. Jakob Kolletschka. Kolletschka was accidentally cut by a student’s scalpel, during a post-mortem examination. The doctor’s own autopsy showed a pathology very similar to those women, dying of childbed fever. Medical students were going from post-mortem examinations of the dead to obstetrical examinations of the living, without washing their hands.

Midwife students had no such contact with the dead. This had to be it. Some unknown “cadaverous material” had to be responsible for the difference.

Semmelweis instituted a mandatory handwashing policy, using a chlorinated lime solution between autopsies and live patient examinations.

Mortality rates in the First Clinic dropped by 90 percent, to rates comparable with the Second. In April 1847, First Clinic mortality rates were 18.3% – nearly one in five. Hand washing was instituted in mid-May, and June rates dropped to 2.2%. July was 1.2%. For two months, the rate actually stood at zero.

The European medical establishment celebrated the doctor’s findings. Semmelweis was feted as the Savior of Mothers, a giant of modern medicine.

No, just kidding. He wasn’t.

The imbecility of the response to Semmelweis’ findings is hard to get your head around and the doctor’s own personality, didn’t help. The medical establishment took offense at the idea that they themselves were the cause of the mortality problem, and that the answer lay in personal hygiene.

Semmelweis himself was anything but tactful, publicly berating those who disagreed with his hypothesis and gaining powerful enemies. For many, the doctor’s ideas were extreme and offensive, ignored or rejected and even ridiculed. Are we not Gentlemen!? Semmelweis was fired from his hospital position and harassed by the Vienna medical establishment, finally forced to move to Budapest.

Dr. Semmelweis was outraged by the indifference of the medical community, and began to write open and increasingly angry letters to prominent European obstetricians. He went so far as to denounce such people as “irresponsible murderers”, leading contemporaries and even his wife, to question his mental stability.

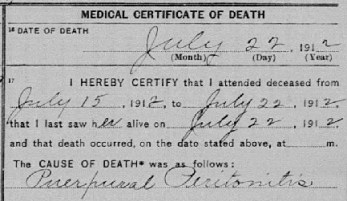

Dr. Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis was committed to an insane asylum on July 31, 1865, twenty-three years before Dr. Louis Pasteur opened his institute for the study of microbiology.

Barely two weeks later, August 12, 1865, British surgeon and scientist Dr. Joseph Lister performed the first anti-septic surgery, in medical history. Dr. Semmelweis died the following day at the age of 47, the victim of a blood infection resulting from a gangrenous wound sustained in a severe beating, by asylum guards.

Childhood memories of standing in line. Smiling. Trusting. And then…the Gun. That sound. Whack! The scream. That feeling of betrayal…being shuffled along. Next!

Childhood memories of standing in line. Smiling. Trusting. And then…the Gun. That sound. Whack! The scream. That feeling of betrayal…being shuffled along. Next!

And did you know? The American Revolution was fought out, entirely in the midst of a smallpox pandemic.

And did you know? The American Revolution was fought out, entirely in the midst of a smallpox pandemic. The idea of inoculation was not new. Terrible outbreaks occurred in Colonial Boston in 1640, 1660, 1677-1680, 1690, 1702, and 1721, killing hundreds, each time. At the time, sickness was considered the act of an angry God. Religious faith frowned on experimentation on the human body.

The idea of inoculation was not new. Terrible outbreaks occurred in Colonial Boston in 1640, 1660, 1677-1680, 1690, 1702, and 1721, killing hundreds, each time. At the time, sickness was considered the act of an angry God. Religious faith frowned on experimentation on the human body. Colonists were chary of the procedure, deeply suspicious of how deliberately infecting a healthy person, could produce a desirable outcome. John Adams submitted to the procedure in 1764 and gave the following account:

Colonists were chary of the procedure, deeply suspicious of how deliberately infecting a healthy person, could produce a desirable outcome. John Adams submitted to the procedure in 1764 and gave the following account: As Supreme Commander, General Washington had a problem. An inoculated soldier would be unfit for weeks before returning to duty. Doing nothing and hoping for the best was to invite catastrophe but so was the inoculation route, as even mildly ill soldiers were contagious and could set off a major outbreak.

As Supreme Commander, General Washington had a problem. An inoculated soldier would be unfit for weeks before returning to duty. Doing nothing and hoping for the best was to invite catastrophe but so was the inoculation route, as even mildly ill soldiers were contagious and could set off a major outbreak.

So it was on December 9, 1979, smallpox was officially described, as eradicated. The only infectious disease ever so declared.

So it was on December 9, 1979, smallpox was officially described, as eradicated. The only infectious disease ever so declared.

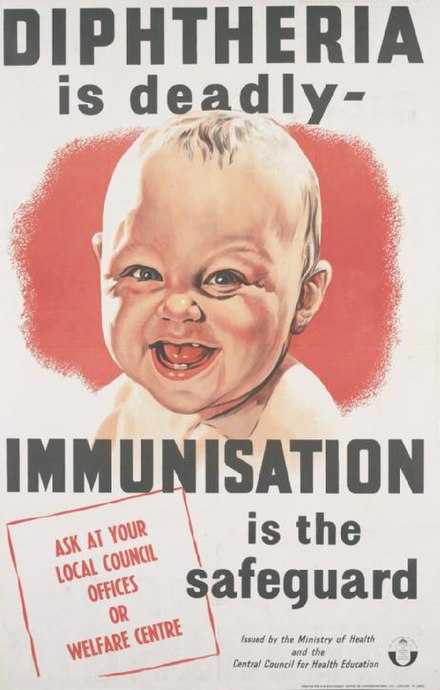

Diphtheria is a highly contagious infection caused by the bacterium Corynebacterium diphtheriae, with early symptoms resembling a cold or flu. Fever, sore throat, and chills lead to bluish skin coloration, painful swallowing, and difficulty breathing.

Diphtheria is a highly contagious infection caused by the bacterium Corynebacterium diphtheriae, with early symptoms resembling a cold or flu. Fever, sore throat, and chills lead to bluish skin coloration, painful swallowing, and difficulty breathing.

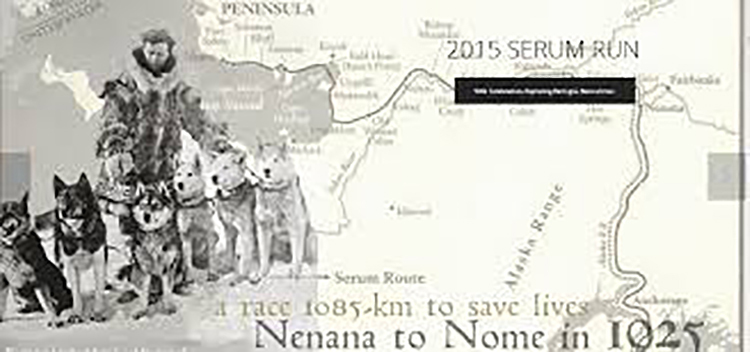

Leonhard Seppala and his dog team took their turn, departing in the face of gale force winds and zero visibility, with a wind chill of −85°F.

Leonhard Seppala and his dog team took their turn, departing in the face of gale force winds and zero visibility, with a wind chill of −85°F.

Seppala was in his old age in 1960, when he recalled “I never had a better dog than Togo. His stamina, loyalty and intelligence could not be improved upon. Togo was the best dog that ever traveled the Alaska trail.”

Seppala was in his old age in 1960, when he recalled “I never had a better dog than Togo. His stamina, loyalty and intelligence could not be improved upon. Togo was the best dog that ever traveled the Alaska trail.”

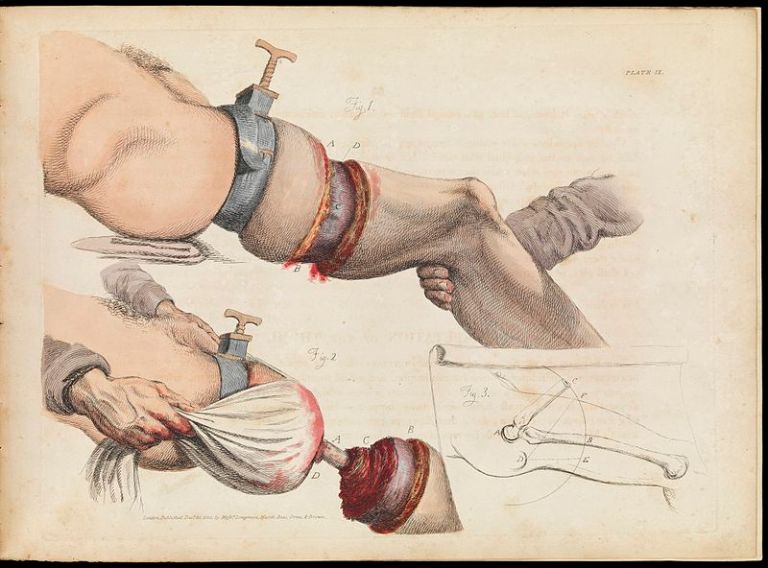

Liston once amputated a leg in 2½ minutes from incision to suture but accidentally severed the poor bastard’s testicles, in the process.

Liston once amputated a leg in 2½ minutes from incision to suture but accidentally severed the poor bastard’s testicles, in the process.

Ordinary flu strains prey most heavily on children, elderly, and those with compromised immune systems. Not this one. This flu would kick off a positive feedback loop between small proteins called cytokines, and white blood cells. This “cytokine storm” resulted in a death rate for 15 to 34-year-olds twenty times higher in 1918, than in previous years.

Ordinary flu strains prey most heavily on children, elderly, and those with compromised immune systems. Not this one. This flu would kick off a positive feedback loop between small proteins called cytokines, and white blood cells. This “cytokine storm” resulted in a death rate for 15 to 34-year-olds twenty times higher in 1918, than in previous years.

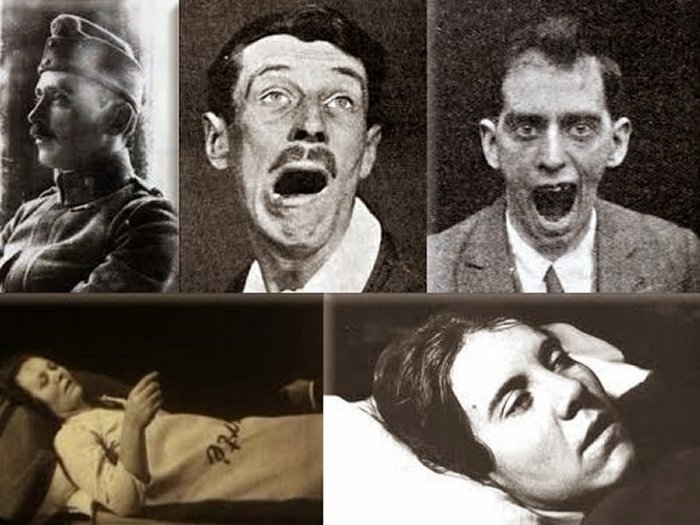

One-third of sufferers died in the acute phase, a higher mortality rate than the Spanish flu of 1918-’19. Many of those who survived never returned to pre-disease states of “aliveness” and lived out the rest of their lives institutionalized, literal prisoners of their own bodies. Living paperweights.

One-third of sufferers died in the acute phase, a higher mortality rate than the Spanish flu of 1918-’19. Many of those who survived never returned to pre-disease states of “aliveness” and lived out the rest of their lives institutionalized, literal prisoners of their own bodies. Living paperweights. Professor John Sydney Oxford is an English virologist, a leading expert on influenza, the 1918 Spanish Influenza, and HIV/AIDS. Few have done more in the modern era, to understand Encephalitis Lethargica: “I certainly do think that whatever caused it could strike again. And until we know what caused it we won’t be able to prevent it happening again.”

Professor John Sydney Oxford is an English virologist, a leading expert on influenza, the 1918 Spanish Influenza, and HIV/AIDS. Few have done more in the modern era, to understand Encephalitis Lethargica: “I certainly do think that whatever caused it could strike again. And until we know what caused it we won’t be able to prevent it happening again.”

Both sides in the battle for Troy used poisoned arrows, according to the Iliad and the Odyssey of Homer. Alexander the great encountered poison arrows and fire weapons in the Indus valley of India, in the fourth century, BC. Chinese chronicles describe an arsenic laden “soul-hunting fog”, used to disperse a peasant revolt, in AD178.

Both sides in the battle for Troy used poisoned arrows, according to the Iliad and the Odyssey of Homer. Alexander the great encountered poison arrows and fire weapons in the Indus valley of India, in the fourth century, BC. Chinese chronicles describe an arsenic laden “soul-hunting fog”, used to disperse a peasant revolt, in AD178. Imperial Germany was first to give serious study to chemical weapons of war, early experiments with irritants taking place at the battle of Neuve-Chapelle in October 1914, and with tear gas at Bolimów on January 31, 1915 and again at Nieuport, that March.

Imperial Germany was first to give serious study to chemical weapons of war, early experiments with irritants taking place at the battle of Neuve-Chapelle in October 1914, and with tear gas at Bolimów on January 31, 1915 and again at Nieuport, that March.

Great Britain possessed massive quantities of mustard, chlorine, Lewisite, Phosgene and Paris Green, awaiting retaliation should Nazi Germany resort to such weapons on the beaches of Normandy. General Alan Brooke, Commander-in-Chief of the Home Forces, “[H]ad every intention of using sprayed mustard gas on the beaches” in the event of a German landing on the British home islands.

Great Britain possessed massive quantities of mustard, chlorine, Lewisite, Phosgene and Paris Green, awaiting retaliation should Nazi Germany resort to such weapons on the beaches of Normandy. General Alan Brooke, Commander-in-Chief of the Home Forces, “[H]ad every intention of using sprayed mustard gas on the beaches” in the event of a German landing on the British home islands. The Geneva Protocols on 1925 banned the use of chemical weapons, but not their manufacture, or transport. By 1942, the U.S. Chemical Corps employed some 60,000 soldiers and civilians and controlled a $1 Billion budget.

The Geneva Protocols on 1925 banned the use of chemical weapons, but not their manufacture, or transport. By 1942, the U.S. Chemical Corps employed some 60,000 soldiers and civilians and controlled a $1 Billion budget.

Death comes in days or weeks. Survivors are likely to suffer chronic respiratory disease and infections. DNA is altered, often resulting in certain cancers and birth defects. To this day there is no antidote.

Death comes in days or weeks. Survivors are likely to suffer chronic respiratory disease and infections. DNA is altered, often resulting in certain cancers and birth defects. To this day there is no antidote.

You must be logged in to post a comment.