During the early colonial period, American newspapers were “wretched little” sheets in the words of America’s “1st newsboy”, Benjamin Franklin. Scarcely more than sidelines to keep presses occupied.

Newspapers were distributed by mail in the early years, thanks to generous subsidies from the Postal Act of 1792. In 1800, the United States could boast somewhere between 150 – 200 newspapers. Thirty-five years later, some 1,200 were competing for readership.

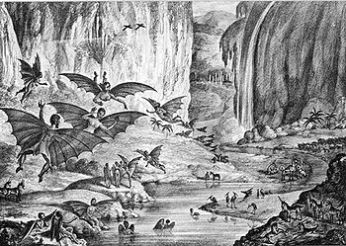

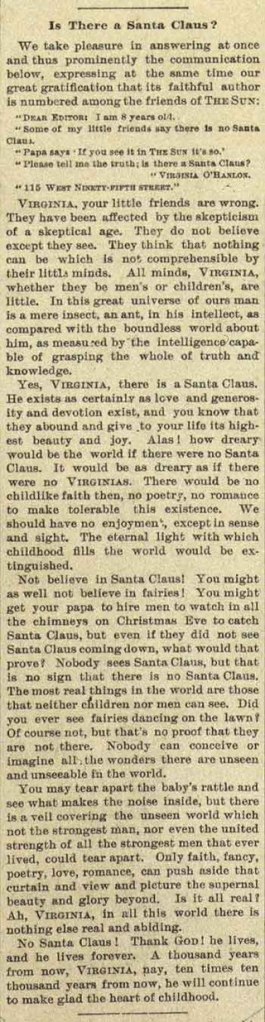

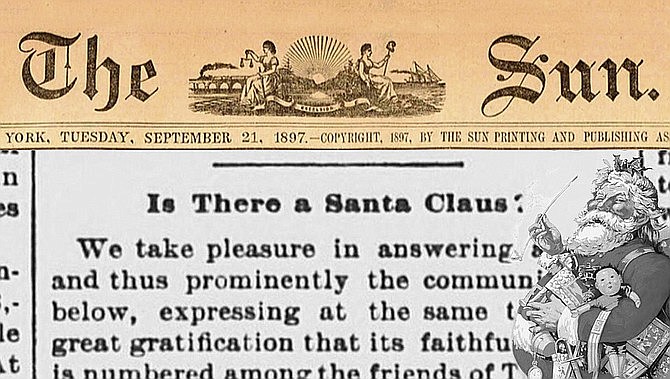

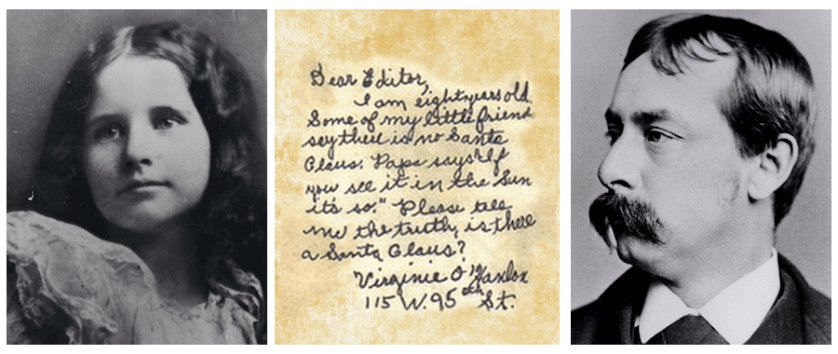

We hear a lot today about “fake news”, but that’s nothing new. In 1835, the New York Sun published a six-part series, about civilization on the moon.

The “Great Moon Hoax”, ostensibly reprinted from the Edinburgh Courant, was falsely attributed to the work of Sir John Herschel, one of the best known astronomers of the time.

Whatever it took, to sell newspapers.

Two years earlier, Sun publisher Benjamin Day ran a Help-Wanted advertisement, looking for adults to help expand circulation. “To the unemployed — A number of steady men can find employment by vending this paper. A liberal discount is allowed to those who buy and sell again“. To Day’s surprise, his ad didn’t produce adult applicants as expected. Instead, the notice attracted children.

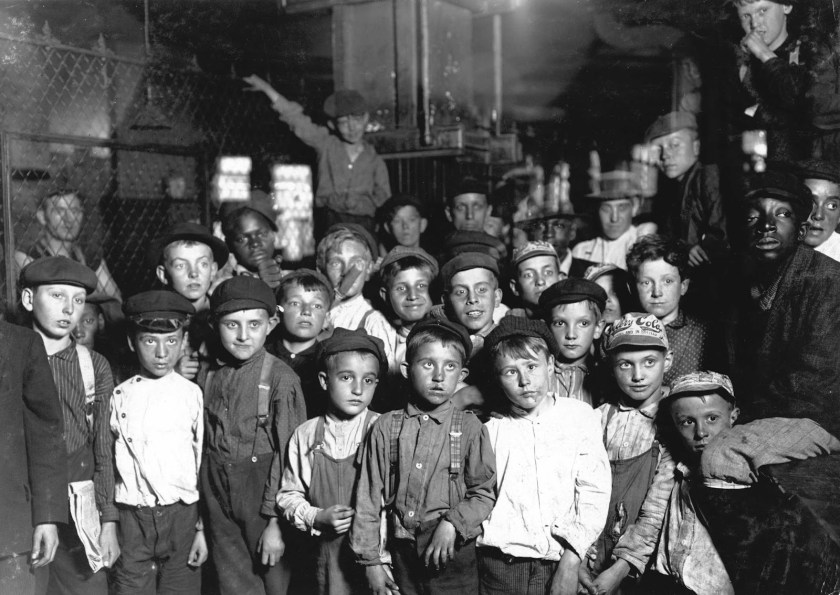

Today, kids make up a minimal part of the American workforce, but that wasn’t always so. Child labor played an integral part in the agricultural and handicraft economy, working on family farms or hiring out to other farmers. Boys customarily apprenticed to the trades, at 10 – 14. Girls went into domestic work. As late as 1900, fully 18% of the American workforce was under the age of sixteen.

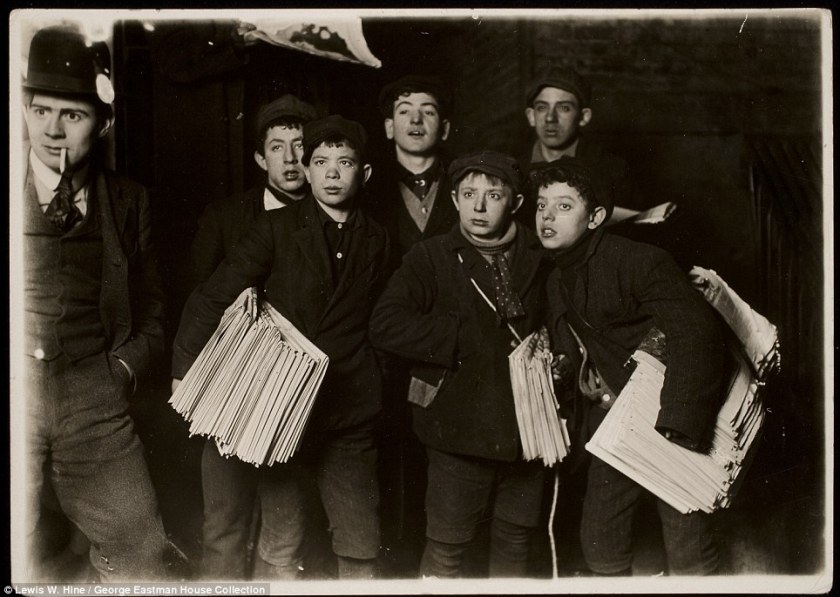

Benjamin Day’s first newspaper “hawker” was Bernard Flaherty, a ten-year-old Irish immigrant. The kid was good at it too, crying out lurid headlines, to passers-by: “Double Distilled Villainy!” “Cursed Effects of Drunkenness!” “Awful Occurrence!” “Infamous Affair!” “Extra! Extra! Read all about it!”

Hordes of street urchins swarmed the tenements and alleyways of American cities. During the 1870s, homeless children were estimated at 20,000 – 30,000 in New York alone, as much as 12% of school-age children in the city.

For thousands of them, newspapers were all that stood in the way of an empty belly.

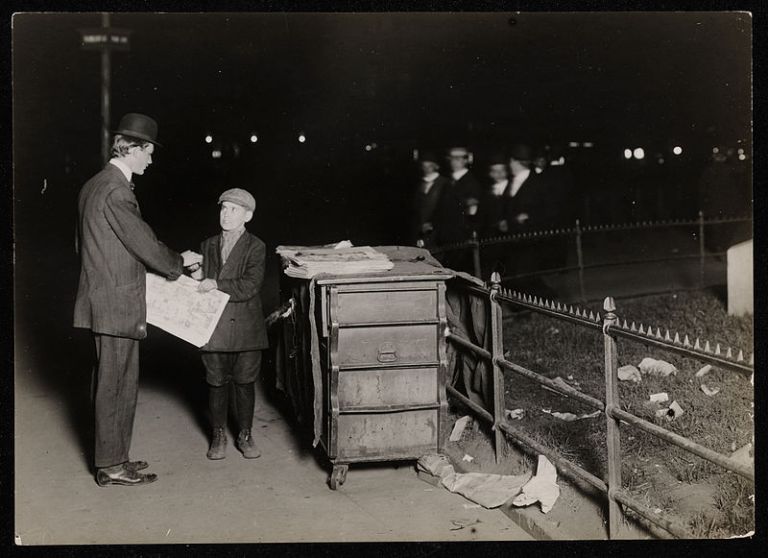

Adults had no interest in the minuscule income, and left the newsboys (and girls) to their own devices. “Newsies” bought papers at discounted prices and peddled them on the street. Others worked saloons and houses of prostitution. They weren’t allowed to return any left unsold, and worked well into the night to sell every paper.

Adults had no interest in the minuscule income, and left the newsboys (and girls) to their own devices. “Newsies” bought papers at discounted prices and peddled them on the street. Others worked saloons and houses of prostitution. They weren’t allowed to return any left unsold, and worked well into the night to sell every paper.

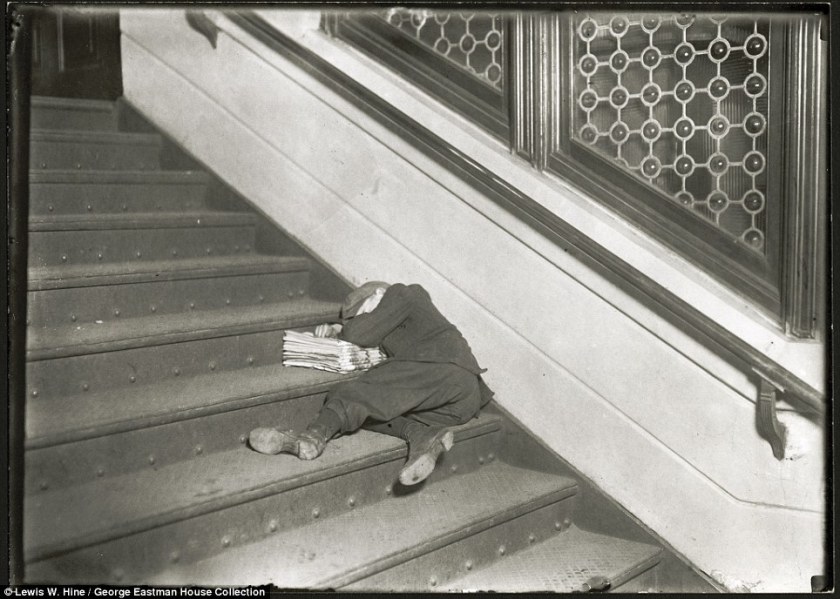

For all that, newsies earned about 30¢ a day. Enough for a bite to eat, to afford enough papers to do it again the following day, and maybe a 5¢ bed in the newsboy’s home.

For all that, newsies earned about 30¢ a day. Enough for a bite to eat, to afford enough papers to do it again the following day, and maybe a 5¢ bed in the newsboy’s home.

Competition was ferocious among hundreds of papers, and business practices were lamentable. In 1886, the Brooklyn Times tried a new idea. The city was expanding rapidly, swallowing up previously independent townships along the Long Island shore. The Times charged Western District newsboys a penny a paper, while Eastern District kids paid 1 1/5¢.

The plan was expected to “push sales vigorously in new directions.” It took about a hot minute for newsies to get wise, when hundreds descended on the Times’ offices with sticks and rocks. On March 29, several police officers and a driver’s bullwhip were needed to get the wagons out of the South 8th Street distribution offices. One of the trucks was overturned, later that day.

That time, the newsboy strike lasted a couple of days, enforced by roving gangs of street kids and “backed by a number of roughs”. In the end, the Times agreed to lower its price to a penny apiece, in all districts. Other such strikes would not be ended so quickly, or so easily.

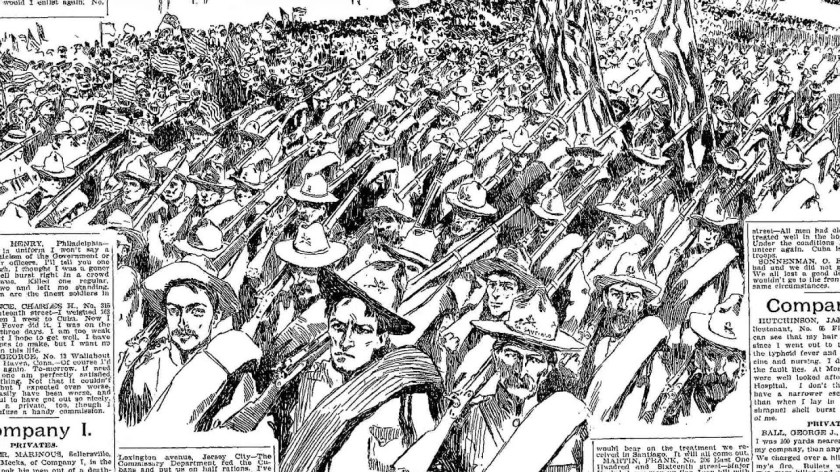

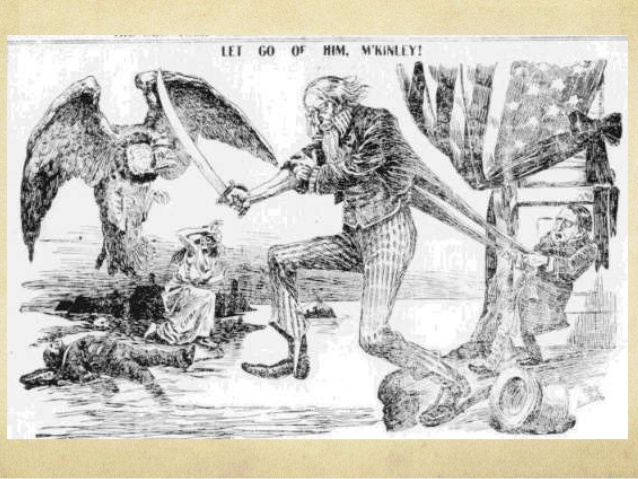

In those days, the Caribbean island of Cuba was ruled from Spain. After decades spent in the struggle for independence, many saw parallels between the “Cuba Libre” movement, and America’s own Revolution of the previous century. In 1897-’98, few wanted war with Spain over Cuban interests more than Assistant Naval Secretary Theodore Roosevelt, and New York publishers Joseph Pulitzer & William Randolph Hearst.

This was the height of the Yellow Journalism period, and newspapers clamored for war. Hearst illustrator Frederic Remington was sent to Cuba, to document “atrocities”. On finding none, Remington wired: “There will be no war. I wish to return”. Hearst wired back: “Please remain. You furnish the pictures, and I’ll furnish the war.” President McKinley urged calm, but agreed to send the armored cruiser USS Maine, to protect US “interests”.

The explosion that sank the Maine on February 15 killing 268 Americans was almost certainly accidental, but that wouldn’t be known for decades. Events quickly spun out of control and, on April 21, 1898, the US blockaded the Caribbean island. Spain gave notice two days later, that it would declare war if US forces invaded its territory. Congress declared on April 25 that a state of war had existed between Spain and the United States, since the 21st. Soon, newsboys were shouting the headline: “How do you like the Journal’s war?

The Spanish-American War was over in 3 months, 3 weeks and 2 days, but circulation was great while it lasted. Publishers cashed in, raising the cost of newsboy bundles from 50¢ to 60¢ – the increase temporarily offset by higher sales. Publishers reverted to 50¢ per 100 after the war, with the notable exceptions of Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World, and William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal.

Newsboys of the era weren’t the ambitious kids of a later age, hustling to make a buck after school. These were orphans and runaways, with little to count on but themselves. The half-cent profit on each paper was all these kids had to get through the day, with a little held back to buy more papers.

50¢ to 60¢ for the same bundle was an insurmountable increase. On July 18, 1899, a group of Long Island newsboys overturned a distribution wagon, refusing to sell Hearst or Pulitzer newspapers until prices were returned to 50¢. Newsboys from Manhattan and Brooklyn joined the strike, the following day.

Boys and men who tried to break the strike were mobbed and beaten, their papers destroyed.

Competing publishers such as the New York Tribune couldn’t get enough of the likes of strike “President” Dave Simmons, the boy “prize-fighter”, Barney “Peanuts”, “Crutch” Morris, and others.

The charismatic, one-eyed strike leader “Kid Blink”, was a favorite:

“Friens and feller workers. This is a time which tries de hearts of men. Dis is de time when we’se got to stick together like glue…. We know wot we wants and we’ll git it even if we is blind”.

The newsboy strike of 1899 lasted two weeks, in which Pulitzer’s New York World plummeted from 360,000 papers a day, to 125,000. Women and girls had more success as strike breakers than boys and men. As Kid Blink put it, “A feller can’t soak a lady.” In the end, it didn’t matter. Most news readers took the side of the strikers. Neither Hearst nor Pulitzer ever dropped their price, but both agreed to buy back unsold papers.

The New York newsboys’ strike of 1899 inspired later strikes including Butte, Montana in 1914, and a 1920s strike in Louisville, Kentucky. In time, changing notions of urban child-welfare led to improvements in the newsboys’ quality of life. For now, street kids had precious few to look out for them, beyond themselves.

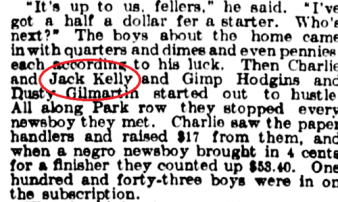

Brooklyn’s “Racetrack Newsie” “Dutch” Johnson caught cold, in 1905. The illness soon turned more serious. He was found unconscious on a pile of catalogs. Brought to Bellevue Hospital by the East River, the 16-year-old was informed it was pneumonia. This was before the age of antibiotics. There was no hope.

“It goes”, Dutch said, in a voice so soft as to be barely audible. “Only I ain’t got no money and I’d like to be put away decent”.

Bookmaker “Con” Shannon offered to take up a collection for the burial. He could’ve easily produced hundreds from bookies and gamblers, but Dutch’s diminutive successor “Boston”, spoke up. “Naw”, he said “we’re on de job and nobody else”.

So it was that “Gimpy”, “Dusty”, and the other urchins of Sheepshead Bay pitched in with their pennies, their nickels and dimes. $53.40 bought a plot in the Linden Hill Cemetery, with a little stone marker. Dutch Johnson would be spared the plain black wagon and the nameless grave, in some anonymous Potter’s Field.

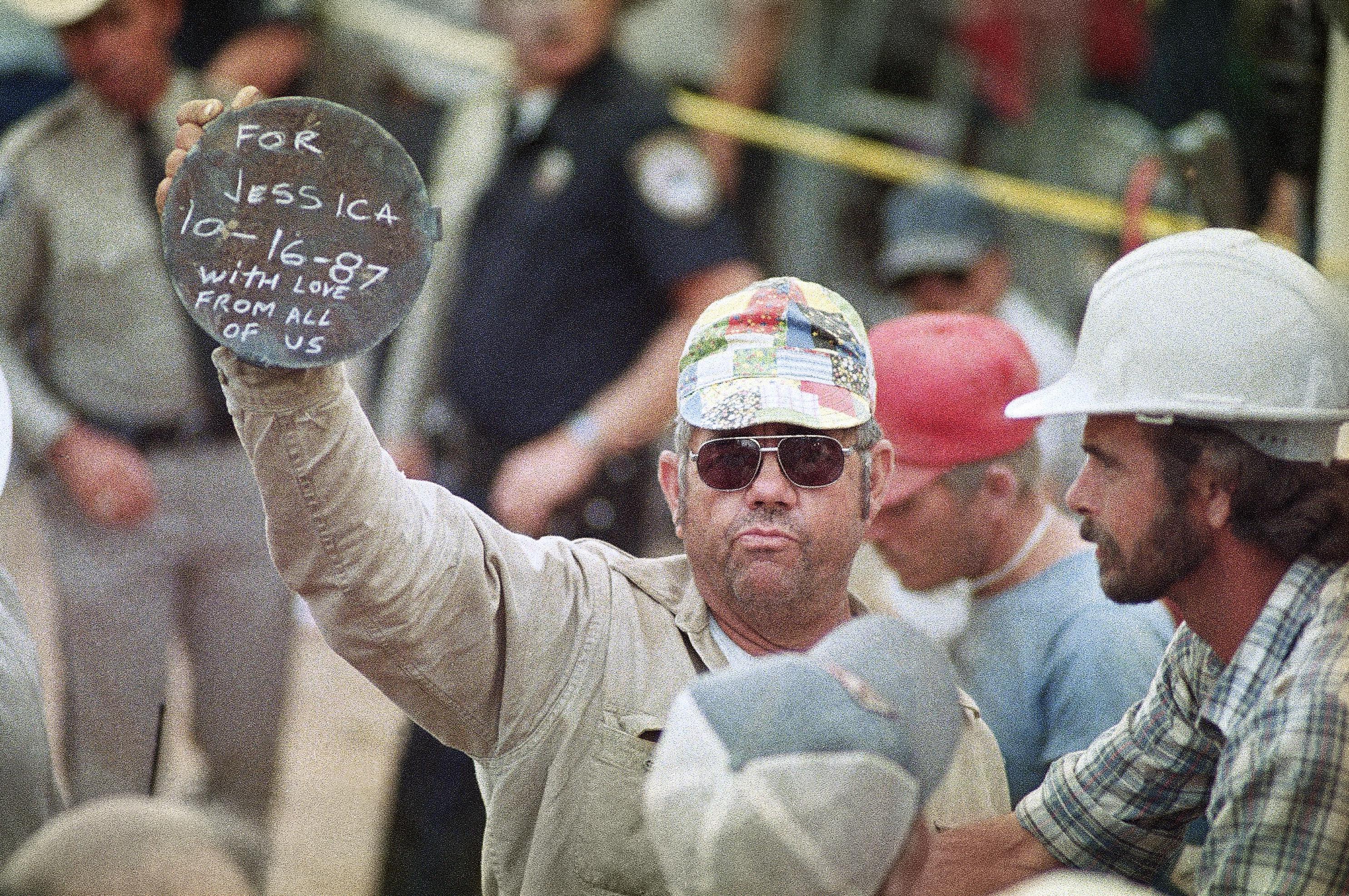

Jessica McClure Morales is 33-years old. A typical West Texas Mom, with two kids and a dog. Her life is normal in every way. She’s a teacher’s aide. Her husband Danny, works for a piping supply outfit.

Jessica McClure Morales is 33-years old. A typical West Texas Mom, with two kids and a dog. Her life is normal in every way. She’s a teacher’s aide. Her husband Danny, works for a piping supply outfit. Midland, Texas first responders quickly devised a plan. A second shaft would be dug, parallel to the well. Then it was left only to bore a tunnel, until rescuers reached the baby. The operation would be over, by dinnertime.

Midland, Texas first responders quickly devised a plan. A second shaft would be dug, parallel to the well. Then it was left only to bore a tunnel, until rescuers reached the baby. The operation would be over, by dinnertime.

These were good signs. A baby could neither sing nor cry, if she could not breathe.

These were good signs. A baby could neither sing nor cry, if she could not breathe. Baby Jessica came out of that well with her face deeply scarred and toes black with gangrene, for lack of blood flow. She required fifteen surgeries before her ordeal was over, but she was alive.

Baby Jessica came out of that well with her face deeply scarred and toes black with gangrene, for lack of blood flow. She required fifteen surgeries before her ordeal was over, but she was alive. The story has a happy ending for baby Jessica. Not so, for many others. The New York Times wrote:

The story has a happy ending for baby Jessica. Not so, for many others. The New York Times wrote: President Ronald Reagan quipped, “Everybody in America became godmothers and godfathers of Jessica while this was going on.” Baby Jessica appeared with her teenage parents Reba and Chip on Live with Regis and Kathie Lee, to talk about the incident. Scott Shaw of the Odessa American won the Pulitzer prize for The photograph. ABC made a television movie: Everybody’s Baby: The Rescue of Jessica McClure. USA Today ranked her 22nd on a list of “25 lives of indelible impact.” Everyone in the story became famous. Until they weren’t.

President Ronald Reagan quipped, “Everybody in America became godmothers and godfathers of Jessica while this was going on.” Baby Jessica appeared with her teenage parents Reba and Chip on Live with Regis and Kathie Lee, to talk about the incident. Scott Shaw of the Odessa American won the Pulitzer prize for The photograph. ABC made a television movie: Everybody’s Baby: The Rescue of Jessica McClure. USA Today ranked her 22nd on a list of “25 lives of indelible impact.” Everyone in the story became famous. Until they weren’t.

In April 1995, O’Donnell’s mother noticed the missing shotgun at the family ranch, in Stanton Texas. The 410 buckshot, loaded with larger pellets intended for bigger game, or self defense. They found the body some 20-miles away, slumped over the wheel of the new Ford pickup. This was no accident. You don’t put a barrel that long into your mouth, without meaning to.

In April 1995, O’Donnell’s mother noticed the missing shotgun at the family ranch, in Stanton Texas. The 410 buckshot, loaded with larger pellets intended for bigger game, or self defense. They found the body some 20-miles away, slumped over the wheel of the new Ford pickup. This was no accident. You don’t put a barrel that long into your mouth, without meaning to.

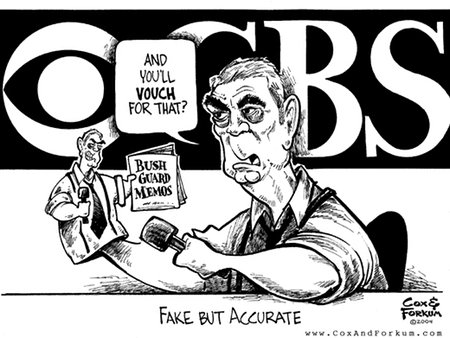

The documents came from Lt. Col. Bill Burkett, a former Texas Army National Guard officer who had received publicity back in 2000, when he claimed to have been transferred to Panama after refusing to falsify then-Governor Bush’s personnel records. Burkett later retracted the claim, but popped up again during the 2004 election cycle. Many considered the man to be an “anti-Bush zealot”.

The documents came from Lt. Col. Bill Burkett, a former Texas Army National Guard officer who had received publicity back in 2000, when he claimed to have been transferred to Panama after refusing to falsify then-Governor Bush’s personnel records. Burkett later retracted the claim, but popped up again during the 2004 election cycle. Many considered the man to be an “anti-Bush zealot”. Meanwhile, the four “experts” used in the original story were publicly repudiating the 60 Minutes piece.

Meanwhile, the four “experts” used in the original story were publicly repudiating the 60 Minutes piece. Yet Killian’s wife and son had cleared out his office after his death, and neither found anything so much as hinting at the existence of such documents. Others who claimed to know Carr well described her as a “sweet old lady”, but said they had “no idea” where those comments had come from.

Yet Killian’s wife and son had cleared out his office after his death, and neither found anything so much as hinting at the existence of such documents. Others who claimed to know Carr well described her as a “sweet old lady”, but said they had “no idea” where those comments had come from. Public confidence in the “Mainstream Media” plummeted. Many saw the episode as a news network lying, and the “Newspaper of Record” swearing by it.

Public confidence in the “Mainstream Media” plummeted. Many saw the episode as a news network lying, and the “Newspaper of Record” swearing by it.

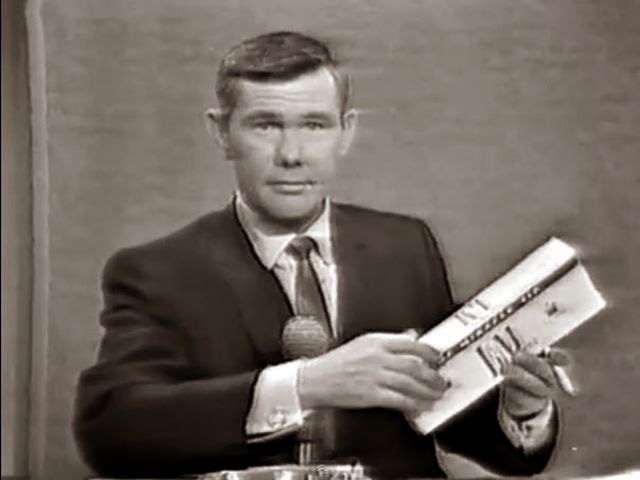

January 2, the following year. The last cigarette ad in the history of American television was a Virginia Slims ad, broadcast at 11:59p.m., January 1, 1971, on the Tonight Show, Starring Johnny Carson. Smoking on-air became a thing of the past sometime in the mid-80s, but that cigarette box remained on Carson’s desk until his final episode, in 1992. You’ve come a long way, baby.

January 2, the following year. The last cigarette ad in the history of American television was a Virginia Slims ad, broadcast at 11:59p.m., January 1, 1971, on the Tonight Show, Starring Johnny Carson. Smoking on-air became a thing of the past sometime in the mid-80s, but that cigarette box remained on Carson’s desk until his final episode, in 1992. You’ve come a long way, baby. Carson began taking Mondays off in 1972, when the show moved from New York to California. There followed a period of rotating guest hosts, including George Carlin and Joan Rivers, who became permanent guest host between 1983 and 1986.

Carson began taking Mondays off in 1972, when the show moved from New York to California. There followed a period of rotating guest hosts, including George Carlin and Joan Rivers, who became permanent guest host between 1983 and 1986. Jay Leno appeared on the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson for the first time on March 2, 1977. He would frequently guest, and served as permanent host from May 1992 to May 2009.

Jay Leno appeared on the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson for the first time on March 2, 1977. He would frequently guest, and served as permanent host from May 1992 to May 2009.

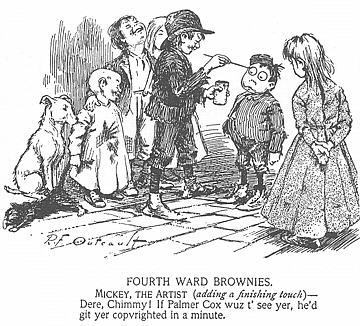

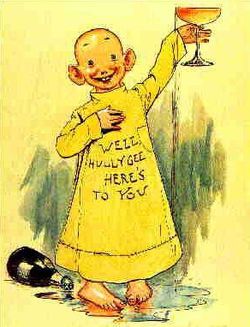

Mickey Dugan was born on February 17, 1895, on the wrong side of the tracks. A wise-cracking street urchin with a “sunny disposition”, Mickey was the kind of street kid you’d find in New York’s turn-of-the-century slums, maybe hawking newspapers. “Extra, Extra, read all about it!”

Mickey Dugan was born on February 17, 1895, on the wrong side of the tracks. A wise-cracking street urchin with a “sunny disposition”, Mickey was the kind of street kid you’d find in New York’s turn-of-the-century slums, maybe hawking newspapers. “Extra, Extra, read all about it!” Outcault’s “Hogan’s Alley” strip, one of the first regular Sunday newspaper cartoons in the country, became colorized in May of 1895. For the first time, Mickey Dugan’s oversized, hand-me-down nightshirt was depicted in yellow. Soon, the character was simply known as “the Yellow kid”.

Outcault’s “Hogan’s Alley” strip, one of the first regular Sunday newspaper cartoons in the country, became colorized in May of 1895. For the first time, Mickey Dugan’s oversized, hand-me-down nightshirt was depicted in yellow. Soon, the character was simply known as “the Yellow kid”. We hear a lot today about “fake news”, but that’s nothing new. Circulation wars were white hot in those days, competing newspapers using anything possible to get an edge. Real-life street urchins hawked lurid headlines, heavy on scandal-mongering and light on verifiable fact. Whatever it took, to increase circulation.

We hear a lot today about “fake news”, but that’s nothing new. Circulation wars were white hot in those days, competing newspapers using anything possible to get an edge. Real-life street urchins hawked lurid headlines, heavy on scandal-mongering and light on verifiable fact. Whatever it took, to increase circulation.

You must be logged in to post a comment.