The “War to end all Wars” exploded across the European continent in the summer of 1914, devolving into the stalemate of trench warfare, by October.

The ‘Great War’ became Total War, the following year. 1915 saw the first use of asphyxiating gas, first at Bolimow in Poland, and later (and more famously) near the Belgian village of Ypres. Ottoman deportation of its Armenian minority led to the systematic extermination of an ethnic minority, resulting in the death of ¾ of an estimated 2 million Armenians living in the Empire at that time, and coining the term ‘genocide‘.

Kaiser Wilhelm responded to the Royal Navy’s near-stranglehold of surface shipping with a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare, as the first zeppelin raids were carried out against the British mainland. German forces adopted a defensive strategy on the western front, developing the most sophisticated defensive capabilities of the war and determined to “bleed France white”, while concentrating on the defeat of Czarist Russia.

Russian Czar Nicholas II took personal command that September, following catastrophic losses in Galicia and Poland. Austro-German offensives resulted in 1.4 million Russian casualties by September with another 750,000 captured, spurring a “Great Retreat” of Russian forces in the east, and resulting in political and social unrest which would topple the Imperial government, fewer than two years later. In December, British and ANZAC forces broke off a meaningless stalemate on the Gallipoli peninsula, beginning the evacuation of some 83,000 survivors. The disastrous offensive had produced some 250,000 casualties. The Gallipoli campaign was remembered as a great Ottoman victory, a defining moment in Turkish history. For now, Turkish troops held their fire in the face of the allied withdrawal, happy to see them leave.

A single day’s fighting in the great battles of 1916 could produce more casualties than every European war of the preceding 100 years, civilian and military, combined. Over 16 million were killed and another 20 million wounded, while vast stretches of the Western European countryside were literally torn apart.

1917 saw the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare, and a German invitation to bring Mexico into the war, against the United States. As expected, these policies brought America into the war on the allied side. The President who won re-election for being ‘too proud to fight’ asked for a congressional declaration of war, that April.

Massive French losses stemming from the failed Nivelle offensive of that same month (French casualties were fully ten times what was expected) combined with irrational expectations that American forces would materialize on the western front led to massive unrest in the French lines. Fully one-half of all French forces on the western front mutinied. It’s one of the great miracles of WW1 that the German side never knew, else the conflict may have ended, very differently.

Massive French losses stemming from the failed Nivelle offensive of that same month (French casualties were fully ten times what was expected) combined with irrational expectations that American forces would materialize on the western front led to massive unrest in the French lines. Fully one-half of all French forces on the western front mutinied. It’s one of the great miracles of WW1 that the German side never knew, else the conflict may have ended, very differently.

The “sealed train‘ carrying the plague bacillus of communism had already entered the Russian body politic. Nicholas II, Emperor of all Russia, was overthrown and murdered that July, along with his wife, children, servants and a few loyal friends, and their dogs.

This was the situation in July 1917.

For eighteen months, British miners worked to dig tunnels under Messines Ridge, the German defensive works laid out around the Belgian town of Ypres. Nearly a million pounds of high explosive were placed in some 2,000′ of tunnels, dug 100′ deep. 10,000 German soldiers ceased to exist at 3:10am local time on June 7, in a blast that could be heard as far away, as London.

For eighteen months, British miners worked to dig tunnels under Messines Ridge, the German defensive works laid out around the Belgian town of Ypres. Nearly a million pounds of high explosive were placed in some 2,000′ of tunnels, dug 100′ deep. 10,000 German soldiers ceased to exist at 3:10am local time on June 7, in a blast that could be heard as far away, as London.

Buoyed by this success and eager to destroy the German submarine bases on the Belgian coast, General Sir Douglas Haig planned an assault from the British-held Ypres salient, near the village of Passchendaele.

British Prime Minister David Lloyd George opposed the offensive, as did the French Chief of the General Staff, General Ferdinand Foch, both preferring to await the arrival of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF). Historians have argued the wisdom of the move, ever since.

The third Battle of Ypres, also known as the Battle of Passchendaele, began in the early morning hours of July 31, 1917. The next 105 days would be fought under some of the most hideous conditions, of the entire war.

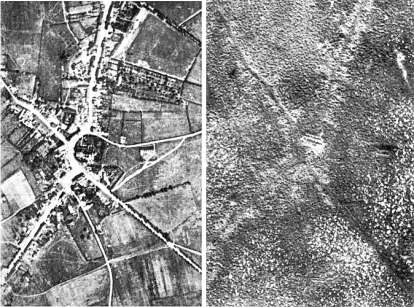

In the ten days leading up to the attack, some 3,000 guns fired an estimated 4½ million shells into German lines, pulverizing whole forests and smashing water control structures in the lowland plains. Several days into the attack, Ypres suffered the heaviest rainfall, in thirty years.

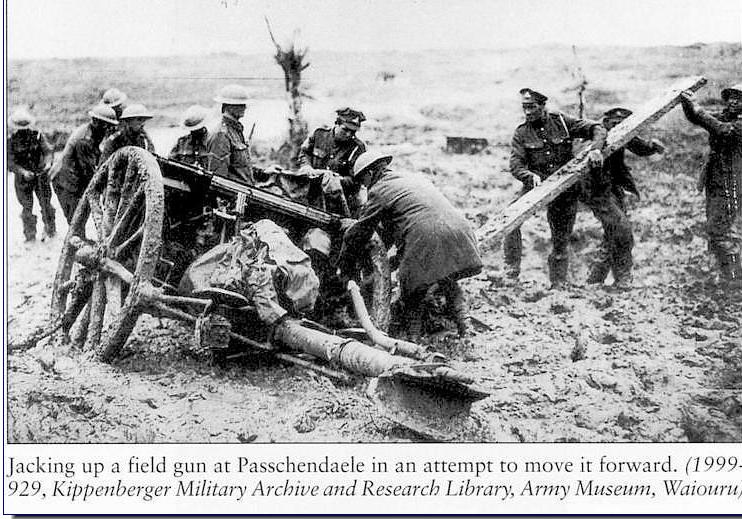

Conditions defy description. Time and again the clay soil, the water, the shattered remnants of once-great forests and the bodies of the slain were churned up and pulverized, by shellfire. You couldn’t call the stuff these people lived and fought in mud – it was more like a thick slime, a clinging, sucking ooze, capable of claiming grown men, even horses and mules. Most of the offensive took place across a broad plain formerly crisscrossed with canals, but now a great, sucking mire in which the only solid ground seemed to be German positions, from which machine guns cut down sodden commonwealth soldiers, as with a scythe.

Soldiers begged for their friends to shoot them, rather than being left to sink in that muck. One sank up to his neck and slowly went stark raving mad, as he died of thirst. British soldier Charles Miles wrote “It was worse when the mud didn’t suck you down; when it yielded under your feet you knew that it was a body you were treading on.”

In 105 days of this hell, Commonwealth forces lost 275,000 killed, wounded and missing. The German side another 200,000. 90,000 bodies were never identified. 42,000 were never recovered and remain there, to this day. All for five miles of mud, and a village barely recognizable, after its capture.

Following the battle of Passchendaele, staff officer Sir Launcelot Kiggell is said to have broken down in tears. “Good God”, he said, “Did we really send men to fight in That”?! The soldier turned war poet Siegfried Sassoon reveals the bitterness of the average “Joe Squaddy” whom his government had sent sent to fight and die, at Passchendaele. The story is told in the first person by a dead man, in all the bitterness of which the poet is capable. It’s called:

Memorial Tablet – by Siegfried Sassoon

“Squire nagged and bullied till I went to fight,

“Squire nagged and bullied till I went to fight,

(Under Lord Derby’s Scheme). I died in hell (They called it Passchendaele). My wound was slight,

And I was hobbling back; and then a shell

Burst slick upon the duck-boards: so I fell

Into the bottomless mud, and lost the light.

At sermon-time, while Squire is in his pew,

He gives my gilded name a thoughtful stare;

For, though low down upon the list, I’m there;

‘In proud and glorious memory’…that’s my due.

Two bleeding years I fought in France, for Squire:

I suffered anguish that he’s never guessed.

Once I came home on leave: and then went west…

What greater glory could a man desire?”

If you enjoyed this “Today in History”, please feel free to re-blog, “like” & share on social media, so that others may find and enjoy it as well. Please click the “follow” button on the right, to receive email updates on new articles. Thank you for your interest, in the history we all share.

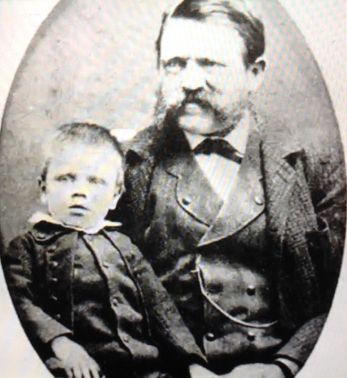

There are plenty of tales regarding the man’s paternity, but none are any more than that. Alois Schicklgruber ‘legitimized’ himself in 1877, adopting a variant on the name of his stepfather and calling himself ‘Hitler”.

There are plenty of tales regarding the man’s paternity, but none are any more than that. Alois Schicklgruber ‘legitimized’ himself in 1877, adopting a variant on the name of his stepfather and calling himself ‘Hitler”.

Following four months of training, Richtofen began his flying career as an observer, taking photographs of Russian troop positions on the eastern front.

Following four months of training, Richtofen began his flying career as an observer, taking photographs of Russian troop positions on the eastern front. Ever aware of his own celebrity, von Richtofen took to painting the wings of his aircraft a brilliant shade of red, after the colors of his old Uhlan regiment. It was only later that he had the whole thing painted. Friend and foe alike knew him as “the Red Knight”, “the Red Devil”, or “’Le Petit Rouge’” and finally, the name that stuck: “the Red Baron”.

Ever aware of his own celebrity, von Richtofen took to painting the wings of his aircraft a brilliant shade of red, after the colors of his old Uhlan regiment. It was only later that he had the whole thing painted. Friend and foe alike knew him as “the Red Knight”, “the Red Devil”, or “’Le Petit Rouge’” and finally, the name that stuck: “the Red Baron”.

The RAF credited Canadian Pilot Captain Roy Brown with shooting Richthofen down, but the angle of the wound suggests that the bullet was fired from the ground. A 2003 PBS documentary demonstrated that Sergeant Cedric Popkin was the person most likely to have killed him, while a 2002 Discovery Channel documentary suggests that it was Gunner W. J. “Snowy” Evans, a Lewis machine gunner with the 53rd Battery, 14th Field Artillery Brigade, Royal Australian Artillery. Just who killed the Red Baron, may never be known with absolute certainty.

The RAF credited Canadian Pilot Captain Roy Brown with shooting Richthofen down, but the angle of the wound suggests that the bullet was fired from the ground. A 2003 PBS documentary demonstrated that Sergeant Cedric Popkin was the person most likely to have killed him, while a 2002 Discovery Channel documentary suggests that it was Gunner W. J. “Snowy” Evans, a Lewis machine gunner with the 53rd Battery, 14th Field Artillery Brigade, Royal Australian Artillery. Just who killed the Red Baron, may never be known with absolute certainty.

Stationed in Deutsch-Ostafrika (German East Africa) and knowing that his sector would be little more than a side show to the greater war effort, Lettow-Vorbeck determined to tie up as many of his adversaries as possible.

Stationed in Deutsch-Ostafrika (German East Africa) and knowing that his sector would be little more than a side show to the greater war effort, Lettow-Vorbeck determined to tie up as many of his adversaries as possible. To his adversaries, disease and parasites were often more dangerous than enemy action. In July 1916, Allied non-battle casualties ran 31 to 1, compared with battle casualties.

To his adversaries, disease and parasites were often more dangerous than enemy action. In July 1916, Allied non-battle casualties ran 31 to 1, compared with battle casualties. At one point in the

At one point in the

Such a blunt refusal was guaranteed to bring unwanted attention from the Nazi regime. Vorbeck’s home and office were searched, his person subject to constant harassment and surveillance. By the end of WWII, the Lion of Africa was destitute. Both of his sons were killed serving in the Wehrmacht, his home in Bremen destroyed by Allied bombs.

Such a blunt refusal was guaranteed to bring unwanted attention from the Nazi regime. Vorbeck’s home and office were searched, his person subject to constant harassment and surveillance. By the end of WWII, the Lion of Africa was destitute. Both of his sons were killed serving in the Wehrmacht, his home in Bremen destroyed by Allied bombs.

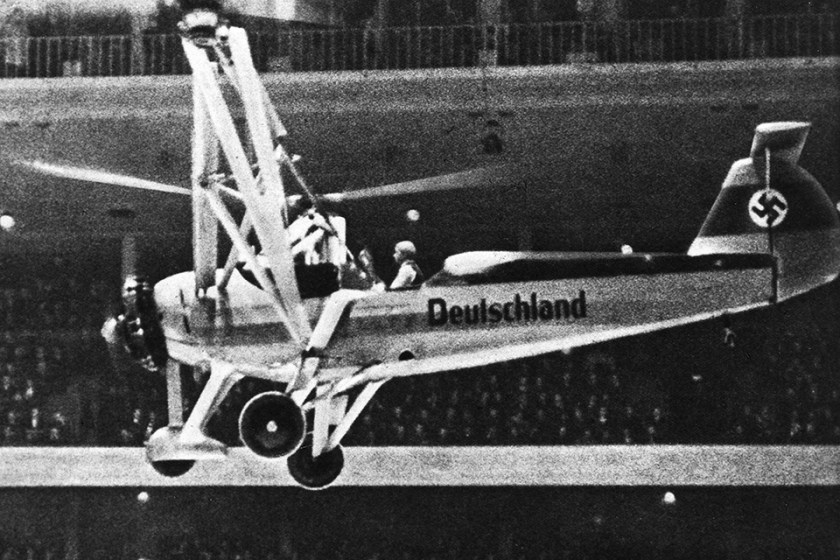

Reitsch began flying gliders in 1932, as the treaty of Versailles prohibited anyone flying “war planes” in Germany. In 1934, she broke the world’s altitude record for women (9,184 feet). In 1936, Reitsch was working on developing dive brakes for gliders, when she was awarded the honorary rank of Flugkapitän, the first woman ever so honored. In 1937 she became a Luftwaffe civilian test pilot. She would hold the position until the end of WW2.

Reitsch began flying gliders in 1932, as the treaty of Versailles prohibited anyone flying “war planes” in Germany. In 1934, she broke the world’s altitude record for women (9,184 feet). In 1936, Reitsch was working on developing dive brakes for gliders, when she was awarded the honorary rank of Flugkapitän, the first woman ever so honored. In 1937 she became a Luftwaffe civilian test pilot. She would hold the position until the end of WW2.

Doctors did not expect her to live, let alone fly again. She spent five months in hospital, and suffered from debilitating dizzy spells. She put herself on a program of climbing trees and rooftops, to regain her sense of balance. Soon, she was test flying again.

Doctors did not expect her to live, let alone fly again. She spent five months in hospital, and suffered from debilitating dizzy spells. She put herself on a program of climbing trees and rooftops, to regain her sense of balance. Soon, she was test flying again. Hitler was initially put off by the idea, though she finally persuaded him to look into modifying a Messerschmitt Me-328B fighter for the purpose. Reitsch put together a suicide group, becoming the first to take the pledge, though the idea would never take shape. The pledge read, in part: “I hereby voluntarily apply to be enrolled in the suicide group as a pilot of a human glider-bomb. I fully understand that employment in this capacity will entail my own death.”

Hitler was initially put off by the idea, though she finally persuaded him to look into modifying a Messerschmitt Me-328B fighter for the purpose. Reitsch put together a suicide group, becoming the first to take the pledge, though the idea would never take shape. The pledge read, in part: “I hereby voluntarily apply to be enrolled in the suicide group as a pilot of a human glider-bomb. I fully understand that employment in this capacity will entail my own death.”

Toward the end of her life, she was interviewed by the Jewish-American photo-journalist, Ron Laytner. Even then she was defiant: “And what have we now in Germany? A land of bankers and car-makers. Even our great army has gone soft. Soldiers wear beards and question orders. I am not ashamed to say I believed in National Socialism. I still wear the Iron Cross with diamonds Hitler gave me. But today in all Germany you can’t find a single person who voted Adolf Hitler into power … Many Germans feel guilty about the war. But they don’t explain the real guilt we share – that we lost“.

Toward the end of her life, she was interviewed by the Jewish-American photo-journalist, Ron Laytner. Even then she was defiant: “And what have we now in Germany? A land of bankers and car-makers. Even our great army has gone soft. Soldiers wear beards and question orders. I am not ashamed to say I believed in National Socialism. I still wear the Iron Cross with diamonds Hitler gave me. But today in all Germany you can’t find a single person who voted Adolf Hitler into power … Many Germans feel guilty about the war. But they don’t explain the real guilt we share – that we lost“.

Martin Luther wrote to Archbishop Albrecht on October 31, 1517, objecting to this sale of indulgences. He enclosed a copy of his “Disputation of Martin Luther on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences”, a document which came to be known as his “95 Theses”.

Martin Luther wrote to Archbishop Albrecht on October 31, 1517, objecting to this sale of indulgences. He enclosed a copy of his “Disputation of Martin Luther on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences”, a document which came to be known as his “95 Theses”.

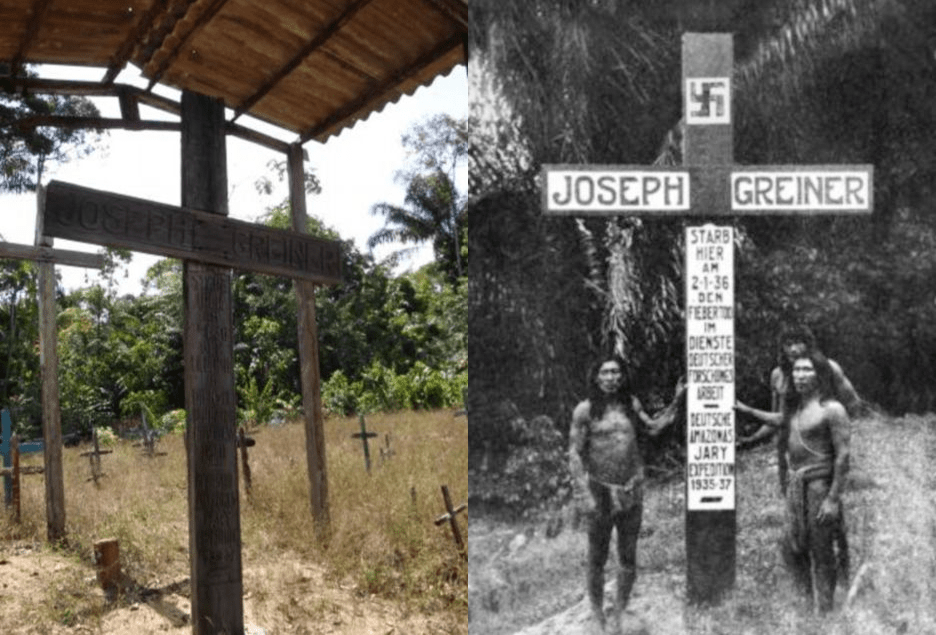

As befitting a man who completely buys into Nazi ideas of racial superiority, the SS officer wrote “For the more advanced white race it offers outstanding possibilities for exploitation”, adding that the people who lived there “cannot be measured in civilised terms as we know them in Germany”.

As befitting a man who completely buys into Nazi ideas of racial superiority, the SS officer wrote “For the more advanced white race it offers outstanding possibilities for exploitation”, adding that the people who lived there “cannot be measured in civilised terms as we know them in Germany”.

A few tried to replicate the event the following year, but there were explicit orders preventing it. Captain Llewelyn Wyn Griffith recorded that after a night of exchanging carols, dawn on Christmas Day 1915 saw a “rush of men from both sides … [and] a feverish exchange of souvenirs” before the men were quickly called back by their officers.

A few tried to replicate the event the following year, but there were explicit orders preventing it. Captain Llewelyn Wyn Griffith recorded that after a night of exchanging carols, dawn on Christmas Day 1915 saw a “rush of men from both sides … [and] a feverish exchange of souvenirs” before the men were quickly called back by their officers. German soldier Richard Schirrmann wrote in December 1915, “When the Christmas bells sounded in the villages of the Vosges behind the lines …. something fantastically unmilitary occurred. German and French troops spontaneously made peace and ceased hostilities; they visited each other through disused trench tunnels, and exchanged wine, cognac and cigarettes for Westphalian black bread, biscuits and ham. This suited them so well that they remained good friends even after Christmas was over”.

German soldier Richard Schirrmann wrote in December 1915, “When the Christmas bells sounded in the villages of the Vosges behind the lines …. something fantastically unmilitary occurred. German and French troops spontaneously made peace and ceased hostilities; they visited each other through disused trench tunnels, and exchanged wine, cognac and cigarettes for Westphalian black bread, biscuits and ham. This suited them so well that they remained good friends even after Christmas was over”. Even so, there is evidence of a small Christmas truce occurring in 1916, previously unknown to historians. 23-year-old Private Ronald MacKinnon of Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, wrote home about German and Canadian soldiers reaching across battle lines near Arras, sharing Christmas greetings and trading gifts. “I had quite a good Christmas considering I was in the front line”, he wrote. “Christmas Eve was pretty stiff, sentry-go up to the hips in mud of course. … We had a truce on Christmas Day and our German friends were quite friendly. They came over to see us and we traded bully beef for cigars”. The letter ends with Private MacKinnon noting that “Christmas was ‘tray bon’, which means very good.”

Even so, there is evidence of a small Christmas truce occurring in 1916, previously unknown to historians. 23-year-old Private Ronald MacKinnon of Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, wrote home about German and Canadian soldiers reaching across battle lines near Arras, sharing Christmas greetings and trading gifts. “I had quite a good Christmas considering I was in the front line”, he wrote. “Christmas Eve was pretty stiff, sentry-go up to the hips in mud of course. … We had a truce on Christmas Day and our German friends were quite friendly. They came over to see us and we traded bully beef for cigars”. The letter ends with Private MacKinnon noting that “Christmas was ‘tray bon’, which means very good.”

Germany installed a Nazi-approved French government in the south of France, headed by WW1 hero Henri Pétain. Though mostly toothless, the self-described “French state” in Vichy was left relatively free to run its own affairs, compared with the Nazi occupied regions to the west and north.

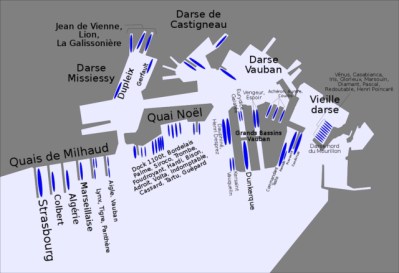

Germany installed a Nazi-approved French government in the south of France, headed by WW1 hero Henri Pétain. Though mostly toothless, the self-described “French state” in Vichy was left relatively free to run its own affairs, compared with the Nazi occupied regions to the west and north. With the armistice of June 1940, much of the French naval fleet was confined to the Mediterranean port of Toulon. Confined but not disarmed, and the French fleet possessed some of the most advanced naval technologies of the age, enough to shift the balance of military power in the Mediterranean.

With the armistice of June 1940, much of the French naval fleet was confined to the Mediterranean port of Toulon. Confined but not disarmed, and the French fleet possessed some of the most advanced naval technologies of the age, enough to shift the balance of military power in the Mediterranean. In November 1942, the Nazi government came to take control of that fleet. The motorized 7th Panzer column of German tanks, armored cars and armored personnel carriers descended on Toulon with an SS motorcycle battalion, taking over port defenses to either side of the harbor. German officers entered fleet headquarters and arrested French officers, but not before word of what was happening was relayed to French Admiral Jean de Laborde, aboard the flagship Strasbourg.

In November 1942, the Nazi government came to take control of that fleet. The motorized 7th Panzer column of German tanks, armored cars and armored personnel carriers descended on Toulon with an SS motorcycle battalion, taking over port defenses to either side of the harbor. German officers entered fleet headquarters and arrested French officers, but not before word of what was happening was relayed to French Admiral Jean de Laborde, aboard the flagship Strasbourg. Under orders to take the harbor without bloodshed, the Nazi commander was dismayed. Was he being denied access by this, his defeated adversary? Minutes seemed like hours in the tense wrangling which followed. Germans gesticulated and argued with French guards, who stalled and prevaricated at the closed gate.

Under orders to take the harbor without bloodshed, the Nazi commander was dismayed. Was he being denied access by this, his defeated adversary? Minutes seemed like hours in the tense wrangling which followed. Germans gesticulated and argued with French guards, who stalled and prevaricated at the closed gate. Finally, the Panzer column could be stalled no more. German tanks rumbled through the main gate at 5:25am, even as the order to scuttle passed throughout the fleet. Dull explosions sounded across the harbor, as fighting broke out between the German column, and French sailors pouring out of their ships in the early dawn light. Lead German tanks broke for the Strasbourg, even now pouring greasy, black smoke from its superstructure, as she settled to the bottom.

Finally, the Panzer column could be stalled no more. German tanks rumbled through the main gate at 5:25am, even as the order to scuttle passed throughout the fleet. Dull explosions sounded across the harbor, as fighting broke out between the German column, and French sailors pouring out of their ships in the early dawn light. Lead German tanks broke for the Strasbourg, even now pouring greasy, black smoke from its superstructure, as she settled to the bottom.

This invasion force, commanded by General Arthur Aitkin, spent that first day and most of the second sweeping for non-existent mines, before finally assembling an assault force on the beaches late on November 3rd. It was a welcome break for the German Commander, Colonel Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck, who had assembled and trained a force of Askari warriors around a core of white German commissioned and non-commissioned officers.

This invasion force, commanded by General Arthur Aitkin, spent that first day and most of the second sweeping for non-existent mines, before finally assembling an assault force on the beaches late on November 3rd. It was a welcome break for the German Commander, Colonel Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck, who had assembled and trained a force of Askari warriors around a core of white German commissioned and non-commissioned officers.

Colonel, and later General Lettow-Vorbeck, was called “

Colonel, and later General Lettow-Vorbeck, was called “ Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck came to loathe Adolf Hitler, and tried to establish a conservative opposition to the Nazi political machine. When offered the ambassadorship to the Court of St. James in 1935, he apparently did more than merely decline the job. He told Der Fuehrer to perform an anatomically improbable act. Years later, Charles Miller asked the nephew of a Schutztruppe officer about the exchange. “I understand that von Lettow told Hitler to go f**k himself”. “That’s right”Came the reply, “except that I don’t think he put it that politely”.

Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck came to loathe Adolf Hitler, and tried to establish a conservative opposition to the Nazi political machine. When offered the ambassadorship to the Court of St. James in 1935, he apparently did more than merely decline the job. He told Der Fuehrer to perform an anatomically improbable act. Years later, Charles Miller asked the nephew of a Schutztruppe officer about the exchange. “I understand that von Lettow told Hitler to go f**k himself”. “That’s right”Came the reply, “except that I don’t think he put it that politely”.

You must be logged in to post a comment.