The Nazi conquest of Europe began with the Sudetenland in 1938, the border districts of Bohemia, Moravia, and German speaking parts of Czechoslovakia. Within two years, every major power on the European mainland was either neutral, or under Nazi occupation.

The island nation of Great Britain alone escaped occupation, but its armed forces were shattered and defenseless in the face of the German war machine.

In May of 1940 the British Expeditionary Force and what remained of French forces occupied a sliver of land along the English Channel. Field Marshall Gerd von Rundstedt called a halt of the German armored advance on May 24, while Hermann Göring urged Hitler to stop the ground assault, let the Luftwaffe finish the destruction of Allied forces. On the other side of the channel, Admiralty officials combed every boatyard they could find for boats to ferry their people off of the beach.

In May of 1940 the British Expeditionary Force and what remained of French forces occupied a sliver of land along the English Channel. Field Marshall Gerd von Rundstedt called a halt of the German armored advance on May 24, while Hermann Göring urged Hitler to stop the ground assault, let the Luftwaffe finish the destruction of Allied forces. On the other side of the channel, Admiralty officials combed every boatyard they could find for boats to ferry their people off of the beach.

Hitler ordered his Panzer groups to resume their advance on May 26, while a National Day of Prayer was declared at Westminster Abbey. That night Winston Churchill ordered “Operation Dynamo”. One of the most miraculous evacuations in military history had begun from the beaches of Dunkirk.

The battered remnants of the French 1st Army fought a desperate delaying action against the advancing Germans. They were 40,000 men against seven full divisions, 3 of them armored. They held out until May 31 when, having run out of food and ammunition, the last 35,000 finally surrendered. Meanwhile, a hastily assembled fleet of 933 vessels large and small began to withdraw the broken army from the beaches.

Larger ships were boarded from piers, while thousands waded into the surf and waited in shoulder deep water for smaller vessels. They came from everywhere: merchant marine boats, fishing boats, pleasure craft, lifeboats and tugs. The smallest among them was the 14’7″ fishing boat “Tamzine”, now in the Imperial War Museum.

A thousand copies of navigational charts helped organize shipping in and out of Dunkirk, as buoys were laid around Goodwin Sands to prevent strandings. Abandoned vehicles were driven into the water at low tide, weighted down with sand bags and connected by wooden planks, forming makeshift jetties.

7,669 were evacuated on May 27, the first full day of the evacuation. By day 9 a total of 338,226 soldiers had been rescued from the beach. The “Miracle of Dunkirk” would remain the largest such waterborne evacuation in history, until September 11, 2001.

It all came to an end on June 4. Most of the light equipment and virtually all the heavy stuff had to be left behind, just to get what remained of the allied armies out alive. But now, with the United States still the better part of a year away from entering the war, the allies had a fighting force that would live to fight on. Winston Churchill delivered a speech that night to the House of Commons, calling the events in France “a colossal military disaster”. “[T]he whole root and core and brain of the British Army”, he said, had been stranded at Dunkirk and seemed about to perish or be captured. In his “We shall fight on the beaches” speech of June 4, Churchill hailed the rescue as a “miracle of deliverance”.

On the home front, thousands of volunteers signed up for a “stay behind” mission in the weeks that followed. With German invasion all but imminent, their mission was to go underground and to disrupt and destabilize the invaders in any way they could. They were to be the British Resistance, a guerrilla force reportedly vetted by a senior Police Chief so secret, that he was to be assassinated in case of invasion to prevent membership in the units from being revealed.

Participants of these auxiliaries were not allowed to tell their families, what they were doing or where they were. Bob Millard, who passed in 2014 at the age of 91, said that they were given 3 weeks’ rations, and that many were issued suicide pills in case of capture. Even Josephine, his wife of 67 years, didn’t know a thing about it until the auxiliaries’ reunion in 1994. “You just didn’t talk about it, really”, he said. “As far as my family were aware I was still in the Home Guard. It was all very hush hush. After the war, it was water under the bridge”.

The word “Cenotaph” literally translates as “Empty Tomb”, in Greek. Every year since 1919 and always taking place on the Sunday closest to the 11th day of the 11th month, the Cenotaph at Whitehall is the site of a remembrance service, commemorating British and Commonwealth servicemen and women who died in 20th century conflicts. Since WWII, the march on the Cenotaph includes members of the Home Guard and the “Bevin Boys”, the 18-25 year old males conscripted to serve in England’s coal mines. In 2013, the last surviving auxiliers joined their colleagues, proudly marching past the Cenotaph for the very first time.

Historians from the Coleshill Auxiliary Research Team (CART) had been trying to do this for years.

CART founder Tom Sykes said: “After over 70 years of silence, the veterans of the Auxiliary Units and Special Duties Section, now more than ever, deserve to get the official recognition that has for so long been lacking. ‘They were, in this country’s hour of need, willing to give up everything, families, friends and ultimately their lives in order to give us a fighting chance of surviving”.

Escadrille N.124 changed its name in December 1916, adopting that of a French hero of the American Revolution. Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette. Five French officers commanded a core group of 38 American volunteers, supported by all-French mechanics and ground crew. Rounding out the Escadrille were the unit mascots, the African lions Whiskey and Soda.

Escadrille N.124 changed its name in December 1916, adopting that of a French hero of the American Revolution. Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette. Five French officers commanded a core group of 38 American volunteers, supported by all-French mechanics and ground crew. Rounding out the Escadrille were the unit mascots, the African lions Whiskey and Soda.

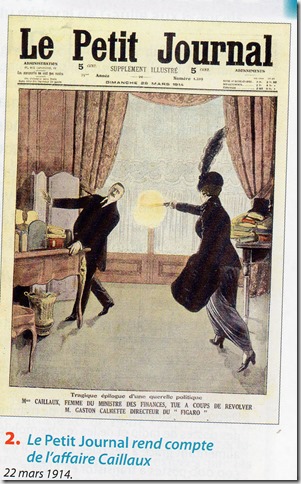

Right, the fall of the powerful, and all the salacious details anyone could ask for. Most of France was riveted by the Caillaux affair in July 1914, ignorant of the European crisis barreling down on them like the four horsemen of the apocalypse. Madame Caillaux’s trial for the murder of Gaston Calmette began on July 20.

Right, the fall of the powerful, and all the salacious details anyone could ask for. Most of France was riveted by the Caillaux affair in July 1914, ignorant of the European crisis barreling down on them like the four horsemen of the apocalypse. Madame Caillaux’s trial for the murder of Gaston Calmette began on July 20.

For the 14-year-old boy-king, even listening to her was an act of desperation, borne of years of humiliating defeats at the hands of the English army. Yet this illiterate peasant girl had made some uncanny predictions concerning battlefield successes. Now she claimed to have had visions from God and the Saints, commanding her to help him gain the throne. Her name was Jeanne d’Arc.

For the 14-year-old boy-king, even listening to her was an act of desperation, borne of years of humiliating defeats at the hands of the English army. Yet this illiterate peasant girl had made some uncanny predictions concerning battlefield successes. Now she claimed to have had visions from God and the Saints, commanding her to help him gain the throne. Her name was Jeanne d’Arc. Compiègne in May, 1430, and her allies failed to come to her aid. Left outside the town’s gates when they closed, she was captured and taken to the castle of Bouvreuil.

Compiègne in May, 1430, and her allies failed to come to her aid. Left outside the town’s gates when they closed, she was captured and taken to the castle of Bouvreuil. The death sentence was carried out on May 30, 1431, in the old marketplace at Rouen. She was 19. After she died, the coals were raked back to expose her charred body. No one would be able to claim she’d escaped alive. Her body was then burned twice more, so no one could collect the relics. Her ashes were then cast into a river.

The death sentence was carried out on May 30, 1431, in the old marketplace at Rouen. She was 19. After she died, the coals were raked back to expose her charred body. No one would be able to claim she’d escaped alive. Her body was then burned twice more, so no one could collect the relics. Her ashes were then cast into a river.

You must be logged in to post a comment.