After three years, the Great War could be likened to two evenly matched and exhausted fighters, each holding the other by the throat while attempting to beat the other to death.

Swaths of the European countryside were literally torn to pieces. Every economy on the continent tottered on the edge of destruction, or close to it. The Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empire were on the edge of extinction. The Russian Empire was dying.

No fewer than 1.7 million Russian troops lay dead at the dawn of 1917, and food shortages plagued the countryside. The Czar was forced to abdicate by February, as the largest belligerent of the war descended into civil war. By March, Imperial Russia was all but out of the war.

The United States entered WW1 relatively late, the first 14,000 Americans arriving ‘over there’ in June 1917. General John ‘Black Jack’ Pershing wanted his troops to be well trained and equipped before entering combat, and refused to disperse them, piecemeal. Desperately wanting the Americans to fill in gaps in his own lines, British Field Marshal Douglas Haig called Pershing ‘Obstinate and Stupid. Ridiculous’. French Marshall Ferdinand Foch was apoplectic, but Pershing refused to allow his people to be used as cannon fodder.

The first small-scale American action occurred that October, near the trenches of Nancy. Meanwhile, a mighty force was building at the French harbors of Bordeaux, La Pallice, Saint Nazaire and Brest. Passenger liners, seized German vessels and borrowed Allied ships poured out of New York, New Jersey, and Newport News, as American engineers built 82 new ship berths, nearly 1,000 miles of railroad track and 100,000 miles of telephone and telegraph lines across the french countryside.

By May 1918, those initial 14,000 had grown to over a million, ‘over there’.

It was imperative at this stage for the German war effort, to throw a knockout punch before the Americans entered in force. With close to 50 divisions freed up from duty in the east following the Russian surrender, Spring of 1918 was time for the ‘King’s Battle’. The Kaiserschlacht.

Operation Michael, the first of four German offensives, exploded against the British 3rd and 5th Armies at 4:40am on March 21. In the space of five hours, 1,100,000 shells were fired into an area 150 miles square. This “Storm of Steel” was followed by storm troopers: fast, elite German infantry armed with flame throwers and small arms, following a moving curtain of fire known as the ‘Feuerwalze’. Rupprecht, Crown Prince of Bavaria, was succinct. “We chop a hole. The rest follows.”

At first, Michael was so successful that German troops outran their own supply lines. The German advance began to falter as exhausted forces faced waves of fresh British and Australian troops. By April 5 the western front was returned to stalemate, at the cost of 255,000 British, British Empire and French troops. 239,000 were lost to the German side.

‘Operation Georgette‘, the Battle of Lys, opened after preliminary bombardment on April 9. The main attack all but destroyed the Portuguese Expeditionary Corps, the British 2nd Division and elements of the British 40th Division. In issuing his “Order of the Day” on April 11, Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig stated, “With our backs to the wall and believing in the justice of our cause, each one of us must fight on to the end.”

Technically a German victory insofar as they held the ground when the shooting stopped, Georgette too was a pyrrhic victory. Killed, wounded and missing stood at roughly 220,000, split evenly between both sides.

Operation Blücher–Yorck, known to history as the Third Battle of the Aisne, began with a German attack on May 27, toward Rheims. The sector was nominally held by six British divisions, badly depleted and basically ‘resting’, following the mauling suffered in earlier fighting. Making matters worse, French General Denis Auguste Duchêne was openly contemptuous of Marshall Philippe Petain’s order to maintain defense in depth, insubordinately massing his troops in forward trenches.

The results of the Feuerwalze were devastating, if not predictable. Allied lines were smashed as German armies poured through, taking 19 kilometers in three days and reaching the Marne River, 50 miles from Paris. On May 31, a dogged defense by the US 3rd Infantry Division turned the German advance at Château-Thierry, and toward Belleau Wood.

The results of the Feuerwalze were devastating, if not predictable. Allied lines were smashed as German armies poured through, taking 19 kilometers in three days and reaching the Marne River, 50 miles from Paris. On May 31, a dogged defense by the US 3rd Infantry Division turned the German advance at Château-Thierry, and toward Belleau Wood.

This and the following week’s fighting earned for the 3rd I.D. the nickname “The Rock of the Marne”. To this day, the unit out of Ft. Stewart, Georgia, is known as the “Marne Division”.

On June 1, German Forces penetrated French lines to the left the US Reserve. The US Army 23rd Infantry Regiment, the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, and an element of the Marine Corps 6th Machine Gun Battalion conducted a forced march overnight, covering over 6 miles to plug the gap and oppose the German line.

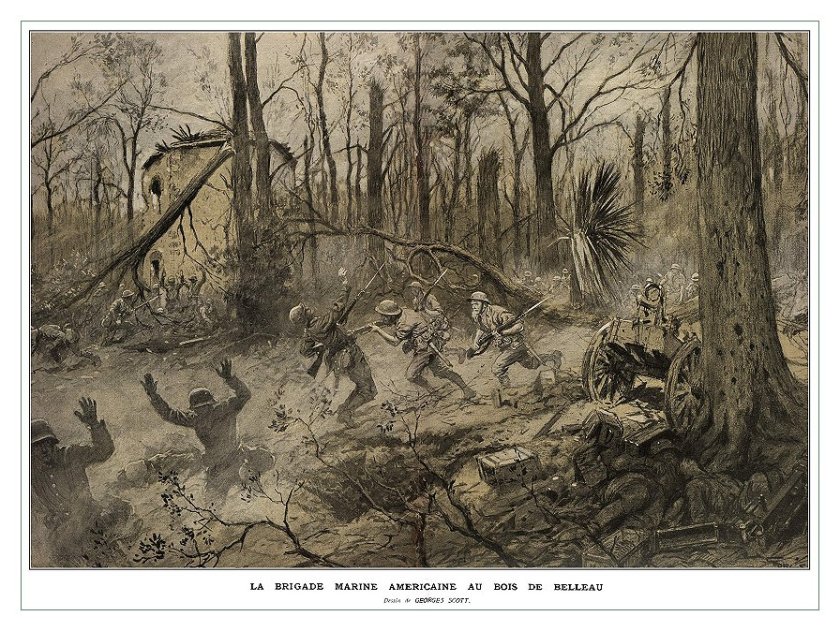

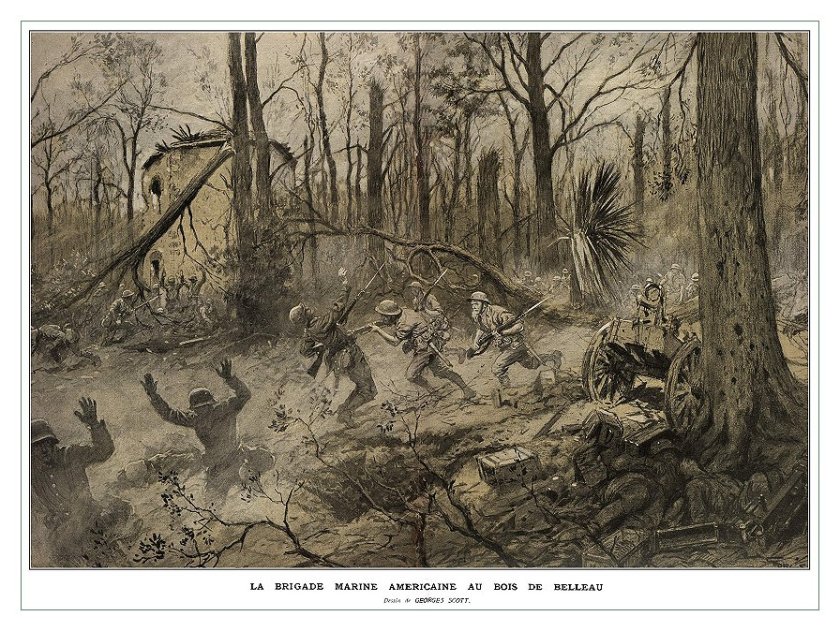

Arriving to find French forces retreating, Marines were urged to turn back. 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines Captain Lloyd Williams’ response would go down in Marine Corps History. “Retreat? Hell, we just got here”. Belleau Wood was one of the bloodiest battles US forces would fight in WW1. Six times over the following days, 5th & 6th Battalion Marines attacked the better part of five German divisions in Belleau Wood. The once-beautiful hunting preserve was reduced to a jungle of shattered timber.

An overwhelmingly superior German force threw everything they had at these two brigades of Marines, a few hundred soldiers and a handful of Navy corpsmen: mustard gas, interlocking and mutually supporting fields of machine gun fire. Fighting became hand to hand with rifle, bayonet and even fists. And still they came.

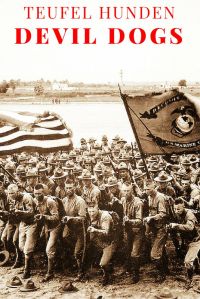

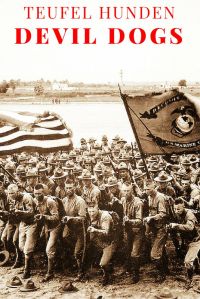

At Belleau Wood, Marines first heard the name “Höllenhunde” (“hellhound”), and the appellation that goes down in Marine Corps lore, to this day. “Teufelshunde”. “Devil Dogs.” In one attack on June 11, only 1 of the 10 Marine officers and 16 out of 250 enlisted men survived, or came out unscathed.

On June 26, Major Maurice Shearer was able to report, “Woods now U.S. Marine Corps entirely,” Belleau Wood was the first major engagement for American forces in WW1. They came out of it with nothing to prove.

On June 30, the French 6th Army Commanding General Jean Degoutte officially renamed Belleau Wood as “Bois de la Brigade de Marine” – Wood of the Marine Brigade.

A German private, one of only 30 men left out of 120, may have had the understatement of the war, when he wrote “We have Americans opposite us who are terribly reckless fellows.”

Sharing Today in History:

Bullard was assigned to the 93d Spad Squadron on August 17, 1917, flying Spad V11s and Nieuports with a mascot, a pet Rhesus Monkey he called “Jimmy”. He said, “I was treated with respect and friendship – even by those from America. Then I knew at last that there are good and bad white men just as there are good and bad black men.”

Bullard was assigned to the 93d Spad Squadron on August 17, 1917, flying Spad V11s and Nieuports with a mascot, a pet Rhesus Monkey he called “Jimmy”. He said, “I was treated with respect and friendship – even by those from America. Then I knew at last that there are good and bad white men just as there are good and bad black men.”

Finally there was no choice for the Grand Armée, but to turn about and go home. Starving and exhausted with no winter clothing, stragglers were frozen in place or picked off by villagers or pursuing Cossacks. From Moscow to the frontiers you could follow their retreat, by the bodies they left in the snow. 685,000 had crossed the Neman River on June 24. By mid-December there were fewer than 70,000 known survivors.

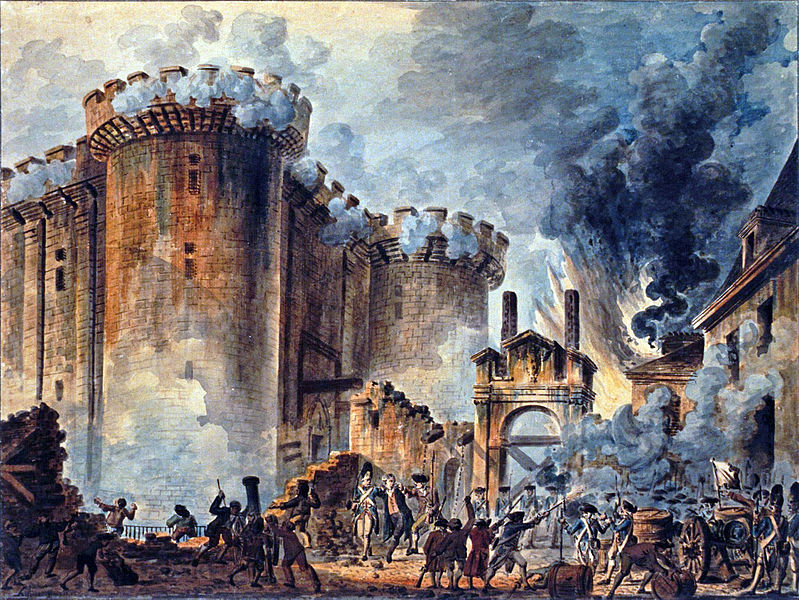

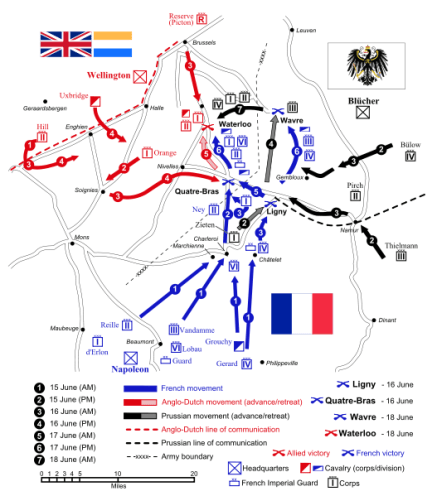

Finally there was no choice for the Grand Armée, but to turn about and go home. Starving and exhausted with no winter clothing, stragglers were frozen in place or picked off by villagers or pursuing Cossacks. From Moscow to the frontiers you could follow their retreat, by the bodies they left in the snow. 685,000 had crossed the Neman River on June 24. By mid-December there were fewer than 70,000 known survivors. The Congress of Vienna declared Napoleon an outlaw on March 13, 1815. Austria, Prussia, Russia and the UK bound themselves to put 150,000 men apiece into the field to end his rule.

The Congress of Vienna declared Napoleon an outlaw on March 13, 1815. Austria, Prussia, Russia and the UK bound themselves to put 150,000 men apiece into the field to end his rule.

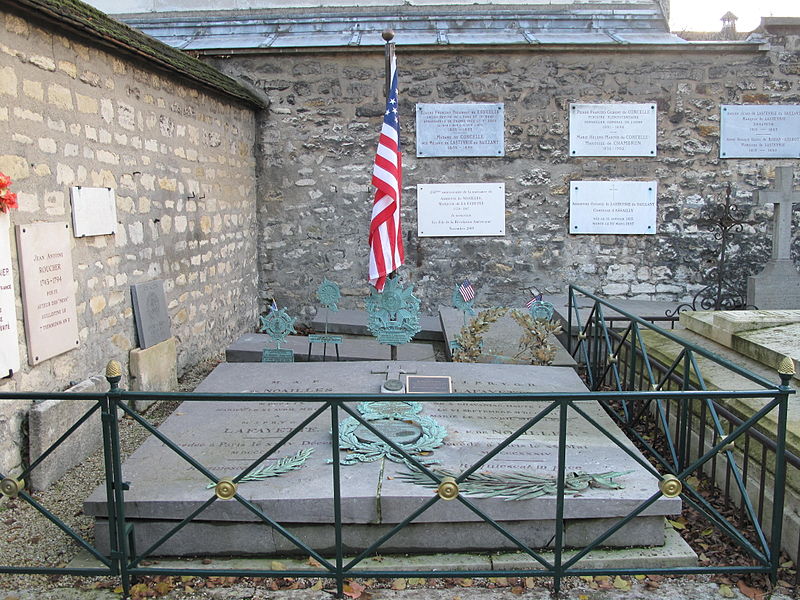

A third would arguably be Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, better known as the Marquis de Lafayette.

A third would arguably be Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, better known as the Marquis de Lafayette.

Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson found a loophole that allowed Lafayette to be paid, with interest, for his services in the late Revolution. An act was rushed through Congress and signed by President Washington, the resulting funds allowing both Lafayettes some of the few privileges permitted them, during their five years’ captivity.

Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson found a loophole that allowed Lafayette to be paid, with interest, for his services in the late Revolution. An act was rushed through Congress and signed by President Washington, the resulting funds allowing both Lafayettes some of the few privileges permitted them, during their five years’ captivity.

It was D+4 in the invasion of

It was D+4 in the invasion of

Most of the political and military establishment lined up against Dreyfus, but the public outcry became furious after writer Émile Zola published his vehement open letter “J’accuse” (I accuse) in the Paris press in January 1898.

Most of the political and military establishment lined up against Dreyfus, but the public outcry became furious after writer Émile Zola published his vehement open letter “J’accuse” (I accuse) in the Paris press in January 1898.

The results of the Feuerwalze were devastating, if not predictable. Allied lines were smashed as German armies poured through, taking 19 kilometers in three days and reaching the Marne River, 50 miles from Paris. On May 31, a dogged defense by the US 3rd Infantry Division turned the German advance at Château-Thierry, and toward Belleau Wood.

The results of the Feuerwalze were devastating, if not predictable. Allied lines were smashed as German armies poured through, taking 19 kilometers in three days and reaching the Marne River, 50 miles from Paris. On May 31, a dogged defense by the US 3rd Infantry Division turned the German advance at Château-Thierry, and toward Belleau Wood.

You must be logged in to post a comment.