There are a handful of men who were indispensable to the American Revolution, men without whom the war effort would have been doomed to failure.

One, of course is George Washington, who became commander in chief before he had an army, before there was even a country. Washington took command of a rebel army with barely enough powder for nine shots per man, knowing all the while that, if caught, the penalty at that time for high treason was to be drawn, quartered and disemboweled, before the dying eyes of the prisoner so convicted.

Another Indispensable would have to be Benjamin Franklin, whose diplomatic skills and unassuming charm elevated him to the status of a rock star among the circles of power at Versailles. It was Benjamin Franklin who transformed the French nation from mildly interested spectator to a crucially important ally.

A third would arguably be Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, better known as the Marquis de Lafayette.

Lafayette was all of nineteen when he arrived in North Island South Carolina on June 13, 1777.

The French King had forbidden him from coming to America, fearing his capture by British agents. Lafayette wanted none of it. His own father, also the Marquis de Lafayette, was killed fighting the British when the boy was only two. The man was going to take part in this contest, if he had to defy his King to do it.

Lafayette disguised himself on departure, and purchased the entire ship’s cargo with his own money, rather than landing in Barbados and thus exposing himself to capture.

Franklin had written to Washington asking him to take the young man on, in hopes of securing an increase in French aid to the American war effort.

The two men bonded almost immediately, forming a relationship closely resembling that of father and son. The fatherless young French officer, and the father of his country who went to his grave, childless.

Lafayette wrote home to his wife in 1778, from Valley Forge. “In the place he occupies, he is surrounded by flatterers and secret enemies. He finds in me a trustworthy friend in whom he can confide and who will always tell him the truth. Not a day goes by without his talking to me at length or writing long letters to me. And he is willing to consult me on most interesting points.”

Lafayette served without pay, spending the equivalent of $200,000 of his own money for the salaries and uniforms of staff, aides and junior officers. He participated in several Revolutionary War battles, including Brandywine, Monmouth Courthouse and the final siege at Yorktown.

All the while, Lafayette periodically returned to France to work with Franklin in securing thousands of additional troops and several warships to aid in the war effort.

Lafayette’s wife Adrienne gave birth to their first child on one such visit, a baby boy the couple would name Georges Washington Lafayette.

Lafayette’s wife Adrienne gave birth to their first child on one such visit, a baby boy the couple would name Georges Washington Lafayette.

It was a small force under Lafayette that took a position on Malvern Hill in 1781, hemming in much larger British forces under Lord Cornwallis at the Yorktown peninsula.

The trap was sprung that September with the arrival of the main French and American armies under the Comte de Rochambeau and General George Washington, and the French fleet’s arrival in the Chesapeake under the Comte de Grasse.

Cornwallis surrendered on October 19, 1781, after which Lafayette returned to France.

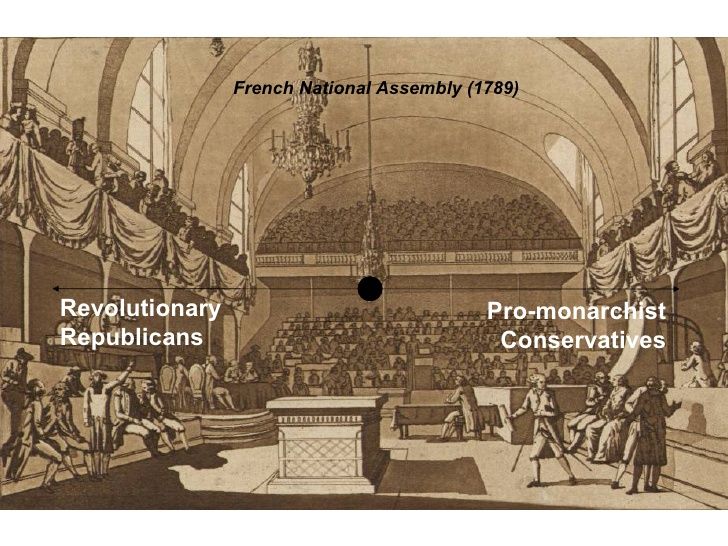

The Marquis played an important role in his own country’s revolution, becoming a Commander of the French National Guard. When the Bastille was stormed by an angry mob in 1789, Lafayette was handed the key. Lafayette later sent the key to the Bastille to George Washington, as a “token of victory by Liberty over Despotism”. Today that key hangs in the main hallway at Washington’s mansion at Mount Vernon.

When the French Marquis died in 1834, President Andrew Jackson ordered that he be accorded the same funeral honors which President John Adams bestowed on George Washington himself, back in 1799. John Quincy Adams delivered the three-hour eulogy in Congress, saying “The name of Lafayette shall stand enrolled upon the annals of our race high on the list of the pure and disinterested benefactors of mankind.”

The Marquis de Lafayette lies under several feet of earth shipped to France from Bunker Hill on the Charlestown peninsula, in obedience to one of his last wishes. He had always wanted to be buried under American soil.

In the late 19th century, Europe was embarked on yet another of its depressingly regular paroxysms of anti-Semitism, when a French Captain of Jewish Alsatian extraction by the name of Alfred Dreyfus was arrested, for selling state secrets to Imperial Germany.

In the late 19th century, Europe was embarked on yet another of its depressingly regular paroxysms of anti-Semitism, when a French Captain of Jewish Alsatian extraction by the name of Alfred Dreyfus was arrested, for selling state secrets to Imperial Germany. Chief Inspector Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Armand Auguste Ferdinand Mercier du Paty de Clam, himself no handwriting expert, agreed with Bertillon. With no file to go on and despite the feebleness of the evidence, de Clam summoned Dreyfus for interrogation on October 13, 1894.

Chief Inspector Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Armand Auguste Ferdinand Mercier du Paty de Clam, himself no handwriting expert, agreed with Bertillon. With no file to go on and despite the feebleness of the evidence, de Clam summoned Dreyfus for interrogation on October 13, 1894.

Most of the political and military establishment lined up against Dreyfus. The public outcry became furious in January 1898 when author Émile Zola published a bitter denunciation in an open letter to the Paris press, entitled “J’accuse” (I Blame).

Most of the political and military establishment lined up against Dreyfus. The public outcry became furious in January 1898 when author Émile Zola published a bitter denunciation in an open letter to the Paris press, entitled “J’accuse” (I Blame).

By that time it wasn’t just the “Party of Order” on the right and the “Party of Movement” on the left. Now, the terms began to describe nuances in political philosophy, as well.

By that time it wasn’t just the “Party of Order” on the right and the “Party of Movement” on the left. Now, the terms began to describe nuances in political philosophy, as well.

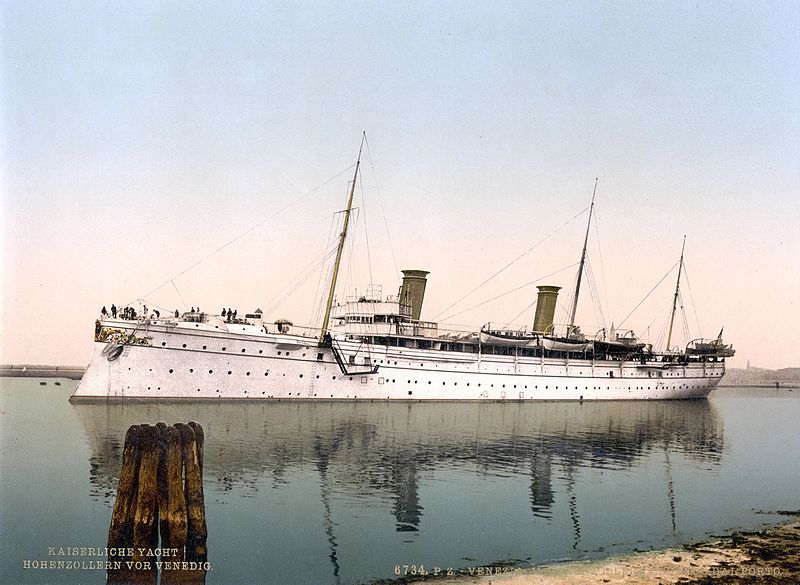

The July Crisis of 1914 was a series of diplomatic maneuverings, culminating in the ultimatum from Austria-Hungary to the Kingdom of Serbia. Vienna, with tacit support from Berlin, made plans to punish Serbia for her role in the assassination, while Russia mobilized armies in support of her Slavic ally.

The July Crisis of 1914 was a series of diplomatic maneuverings, culminating in the ultimatum from Austria-Hungary to the Kingdom of Serbia. Vienna, with tacit support from Berlin, made plans to punish Serbia for her role in the assassination, while Russia mobilized armies in support of her Slavic ally.

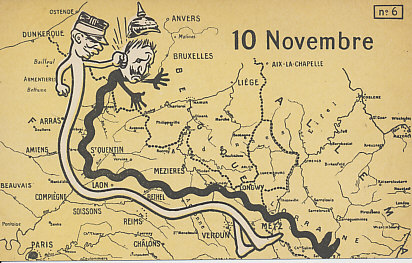

In the days that followed, the Czar would begin the mobilization of men and machines which would place Imperial Russia on a war footing. Kaiser Wilhelm’s Germany invaded Belgium, in pursuit of the one-two punch strategy by which it sought first to defeat France, before turning to face the “Russian Steamroller”. England declared war in support of a 75-year-old commitment to protect Belgian neutrality, a treaty obligation German diplomats had dismissed as a “

In the days that followed, the Czar would begin the mobilization of men and machines which would place Imperial Russia on a war footing. Kaiser Wilhelm’s Germany invaded Belgium, in pursuit of the one-two punch strategy by which it sought first to defeat France, before turning to face the “Russian Steamroller”. England declared war in support of a 75-year-old commitment to protect Belgian neutrality, a treaty obligation German diplomats had dismissed as a “

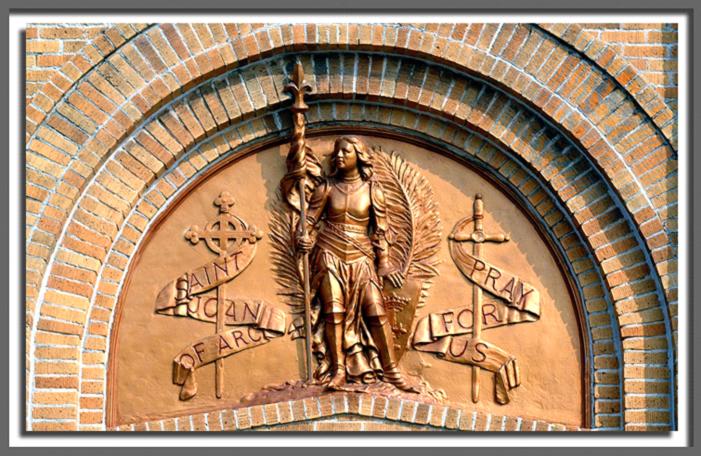

Some 70 charges were made against her by the pro-English Bishop of Beauvais, Pierre Cauchon, including witchcraft, heresy, and perjury.

Some 70 charges were made against her by the pro-English Bishop of Beauvais, Pierre Cauchon, including witchcraft, heresy, and perjury. After fifteen such interrogations her inquisitors still had nothing on her, save for the wearing of soldier’s garb, and her visions. Yet, the outcome of her “trial” was already determined. She was found guilty of heresy, and sentenced to be burned at the stake.

After fifteen such interrogations her inquisitors still had nothing on her, save for the wearing of soldier’s garb, and her visions. Yet, the outcome of her “trial” was already determined. She was found guilty of heresy, and sentenced to be burned at the stake.

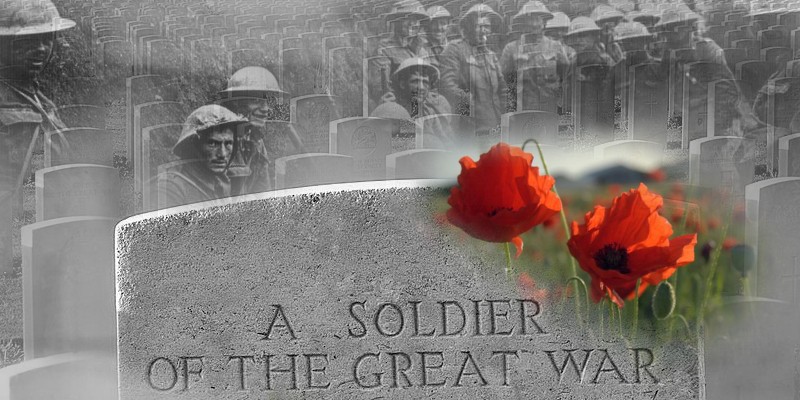

A few tried to replicate the event the following year, but there were explicit orders preventing it. Captain Llewelyn Wyn Griffith recorded that after a night of exchanging carols, dawn on Christmas Day 1915 saw a “rush of men from both sides … [and] a feverish exchange of souvenirs” before the men were quickly called back by their officers.

A few tried to replicate the event the following year, but there were explicit orders preventing it. Captain Llewelyn Wyn Griffith recorded that after a night of exchanging carols, dawn on Christmas Day 1915 saw a “rush of men from both sides … [and] a feverish exchange of souvenirs” before the men were quickly called back by their officers. German soldier Richard Schirrmann wrote in December 1915, “When the Christmas bells sounded in the villages of the Vosges behind the lines …. something fantastically unmilitary occurred. German and French troops spontaneously made peace and ceased hostilities; they visited each other through disused trench tunnels, and exchanged wine, cognac and cigarettes for Westphalian black bread, biscuits and ham. This suited them so well that they remained good friends even after Christmas was over”.

German soldier Richard Schirrmann wrote in December 1915, “When the Christmas bells sounded in the villages of the Vosges behind the lines …. something fantastically unmilitary occurred. German and French troops spontaneously made peace and ceased hostilities; they visited each other through disused trench tunnels, and exchanged wine, cognac and cigarettes for Westphalian black bread, biscuits and ham. This suited them so well that they remained good friends even after Christmas was over”. Even so, there is evidence of a small Christmas truce occurring in 1916, previously unknown to historians. 23-year-old Private Ronald MacKinnon of Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, wrote home about German and Canadian soldiers reaching across battle lines near Arras, sharing Christmas greetings and trading gifts. “I had quite a good Christmas considering I was in the front line”, he wrote. “Christmas Eve was pretty stiff, sentry-go up to the hips in mud of course. … We had a truce on Christmas Day and our German friends were quite friendly. They came over to see us and we traded bully beef for cigars”. The letter ends with Private MacKinnon noting that “Christmas was ‘tray bon’, which means very good.”

Even so, there is evidence of a small Christmas truce occurring in 1916, previously unknown to historians. 23-year-old Private Ronald MacKinnon of Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, wrote home about German and Canadian soldiers reaching across battle lines near Arras, sharing Christmas greetings and trading gifts. “I had quite a good Christmas considering I was in the front line”, he wrote. “Christmas Eve was pretty stiff, sentry-go up to the hips in mud of course. … We had a truce on Christmas Day and our German friends were quite friendly. They came over to see us and we traded bully beef for cigars”. The letter ends with Private MacKinnon noting that “Christmas was ‘tray bon’, which means very good.”

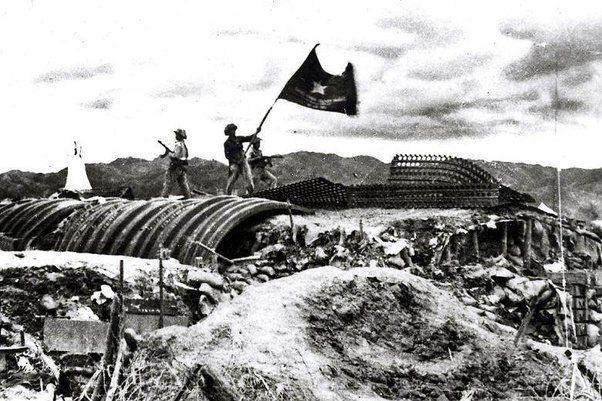

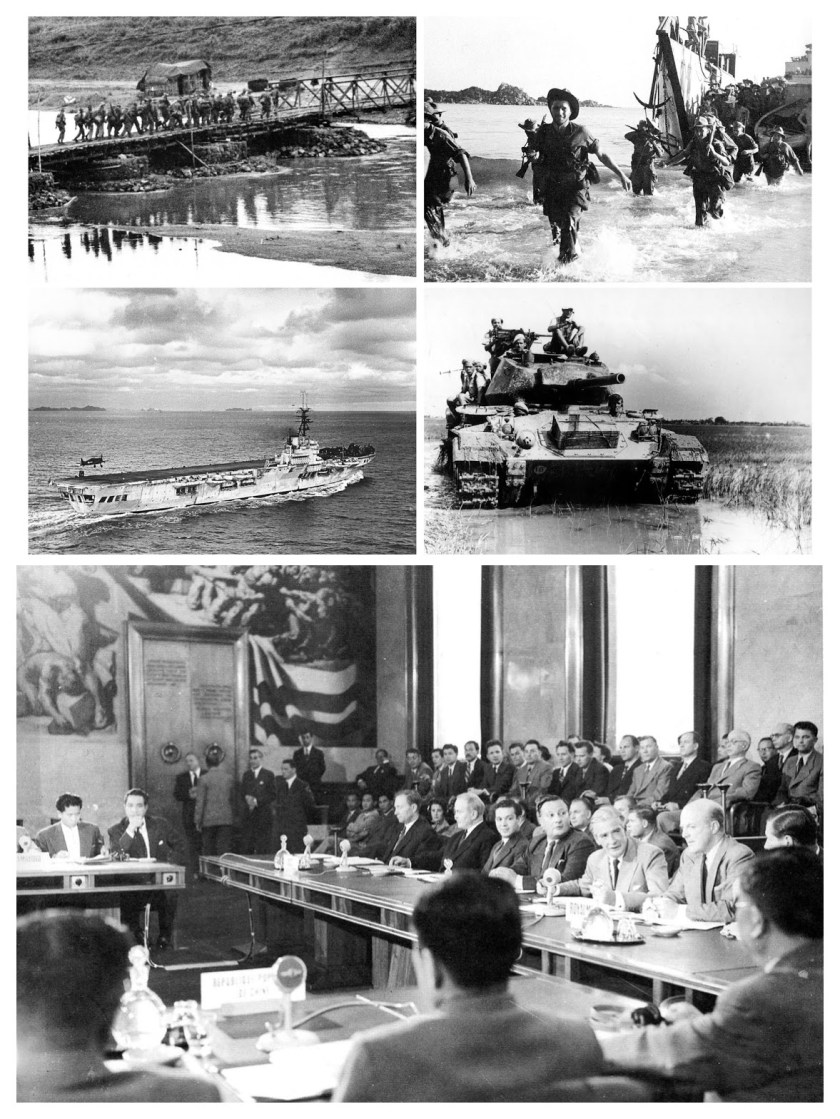

What historians call the First Indochina War, many contemporaries called “la sale guerre”, or “dirty war”. The government forbade the use of metropolitan recruits, fearing that that would make the war more unpopular than it already was. Instead, French professional soldiers and units of the French Foreign Legion were augmented with colonial troops, including Moroccan, Algerian, Tunisian, Laotian, Cambodian, and Vietnamese ethnic minorities.

What historians call the First Indochina War, many contemporaries called “la sale guerre”, or “dirty war”. The government forbade the use of metropolitan recruits, fearing that that would make the war more unpopular than it already was. Instead, French professional soldiers and units of the French Foreign Legion were augmented with colonial troops, including Moroccan, Algerian, Tunisian, Laotian, Cambodian, and Vietnamese ethnic minorities. The war went poorly for the French. By 1952 they were looking for a way out. Premier René Mayer appointed Henri Navarre to take command of French Union Forces in May of that year, with a single order. Navarre was to create military conditions which would lead to an “honorable political solution”.

The war went poorly for the French. By 1952 they were looking for a way out. Premier René Mayer appointed Henri Navarre to take command of French Union Forces in May of that year, with a single order. Navarre was to create military conditions which would lead to an “honorable political solution”. In June, Major General René Cogny proposed a “mooring point” at Dien Bien Phu, creating a lightly defended point from which to launch raids. Navarre wanted to replicate the Na San strategy, and ordered that Dien Bien Phu be taken and converted into a heavily fortified base.

In June, Major General René Cogny proposed a “mooring point” at Dien Bien Phu, creating a lightly defended point from which to launch raids. Navarre wanted to replicate the Na San strategy, and ordered that Dien Bien Phu be taken and converted into a heavily fortified base. The French staff made their battle plan, based on the assumption that it was impossible for the Viet Minh to place enough artillery on the surrounding high ground, due to the rugged terrain. The communists didn’t possess enough artillery to do serious damage anyway, or so they thought.

The French staff made their battle plan, based on the assumption that it was impossible for the Viet Minh to place enough artillery on the surrounding high ground, due to the rugged terrain. The communists didn’t possess enough artillery to do serious damage anyway, or so they thought.

Germany installed a Nazi-approved French government in the south of France, headed by WW1 hero Henri Pétain. Though mostly toothless, the self-described “French state” in Vichy was left relatively free to run its own affairs, compared with the Nazi occupied regions to the west and north.

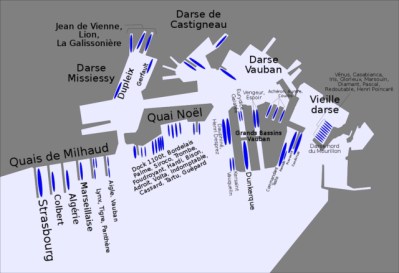

Germany installed a Nazi-approved French government in the south of France, headed by WW1 hero Henri Pétain. Though mostly toothless, the self-described “French state” in Vichy was left relatively free to run its own affairs, compared with the Nazi occupied regions to the west and north. With the armistice of June 1940, much of the French naval fleet was confined to the Mediterranean port of Toulon. Confined but not disarmed, and the French fleet possessed some of the most advanced naval technologies of the age, enough to shift the balance of military power in the Mediterranean.

With the armistice of June 1940, much of the French naval fleet was confined to the Mediterranean port of Toulon. Confined but not disarmed, and the French fleet possessed some of the most advanced naval technologies of the age, enough to shift the balance of military power in the Mediterranean. In November 1942, the Nazi government came to take control of that fleet. The motorized 7th Panzer column of German tanks, armored cars and armored personnel carriers descended on Toulon with an SS motorcycle battalion, taking over port defenses to either side of the harbor. German officers entered fleet headquarters and arrested French officers, but not before word of what was happening was relayed to French Admiral Jean de Laborde, aboard the flagship Strasbourg.

In November 1942, the Nazi government came to take control of that fleet. The motorized 7th Panzer column of German tanks, armored cars and armored personnel carriers descended on Toulon with an SS motorcycle battalion, taking over port defenses to either side of the harbor. German officers entered fleet headquarters and arrested French officers, but not before word of what was happening was relayed to French Admiral Jean de Laborde, aboard the flagship Strasbourg. Under orders to take the harbor without bloodshed, the Nazi commander was dismayed. Was he being denied access by this, his defeated adversary? Minutes seemed like hours in the tense wrangling which followed. Germans gesticulated and argued with French guards, who stalled and prevaricated at the closed gate.

Under orders to take the harbor without bloodshed, the Nazi commander was dismayed. Was he being denied access by this, his defeated adversary? Minutes seemed like hours in the tense wrangling which followed. Germans gesticulated and argued with French guards, who stalled and prevaricated at the closed gate. Finally, the Panzer column could be stalled no more. German tanks rumbled through the main gate at 5:25am, even as the order to scuttle passed throughout the fleet. Dull explosions sounded across the harbor, as fighting broke out between the German column, and French sailors pouring out of their ships in the early dawn light. Lead German tanks broke for the Strasbourg, even now pouring greasy, black smoke from its superstructure, as she settled to the bottom.

Finally, the Panzer column could be stalled no more. German tanks rumbled through the main gate at 5:25am, even as the order to scuttle passed throughout the fleet. Dull explosions sounded across the harbor, as fighting broke out between the German column, and French sailors pouring out of their ships in the early dawn light. Lead German tanks broke for the Strasbourg, even now pouring greasy, black smoke from its superstructure, as she settled to the bottom.

There was a second, ceremonial wedding held in May, after which came the ritual bedding. This wasn’t the couple quietly retiring to their own private space. This was the bizarre spectacle of a room full of courtiers, peering down at the proceedings, to make sure the marriage was consummated.

There was a second, ceremonial wedding held in May, after which came the ritual bedding. This wasn’t the couple quietly retiring to their own private space. This was the bizarre spectacle of a room full of courtiers, peering down at the proceedings, to make sure the marriage was consummated. Louis-Auguste was crowned Louis XVI, King of France, on June 11, 1775. Antoinette remained by his side, though she was never crowned Queen, instead remaining Louis’ “Queen Consort”.

Louis-Auguste was crowned Louis XVI, King of France, on June 11, 1775. Antoinette remained by his side, though she was never crowned Queen, instead remaining Louis’ “Queen Consort”.

Unrest turned to barbarity as Antoinette’s friend and supporter, the Princesse de Lamballe, was taken by the Paris Commune for interrogation. She was murdered at La Force prison, her head fixed on a pike and marched through the city.

Unrest turned to barbarity as Antoinette’s friend and supporter, the Princesse de Lamballe, was taken by the Paris Commune for interrogation. She was murdered at La Force prison, her head fixed on a pike and marched through the city. Marie-Antoinette’s hair was cut off on October 16, 1793. She was driven through Paris in an ox cart, taken to the Place de la Révolution, and decapitated. She accidentally stepped on the executioner’s foot on mounting the scaffold. Her last words were “Pardon me sir, I meant not to do it”.

Marie-Antoinette’s hair was cut off on October 16, 1793. She was driven through Paris in an ox cart, taken to the Place de la Révolution, and decapitated. She accidentally stepped on the executioner’s foot on mounting the scaffold. Her last words were “Pardon me sir, I meant not to do it”.

the nearby town of Chartres under siege. Normans had burned the place to the ground back in 858 and would probably have done so again, but for their defeat at the battle of Chartres on July 20.

the nearby town of Chartres under siege. Normans had burned the place to the ground back in 858 and would probably have done so again, but for their defeat at the battle of Chartres on July 20. The deal made sense for the King, because he had already bankrupted his treasury paying these people tribute. And what better way to deal with future Viking raids down the channel, than to make them the Vikings’ own problem?

The deal made sense for the King, because he had already bankrupted his treasury paying these people tribute. And what better way to deal with future Viking raids down the channel, than to make them the Vikings’ own problem? the symbolic importance of the gesture, but wasn’t about to submit to such degradation himself. The chieftain motioned to one of his lieutenants, a man almost as huge as himself, to kiss the king’s foot. The man shrugged, reached down and lifted King Charles off the ground by his ankle. He kissed the foot, and tossed the King of the Franks aside. Like a sack of potatoes

the symbolic importance of the gesture, but wasn’t about to submit to such degradation himself. The chieftain motioned to one of his lieutenants, a man almost as huge as himself, to kiss the king’s foot. The man shrugged, reached down and lifted King Charles off the ground by his ankle. He kissed the foot, and tossed the King of the Franks aside. Like a sack of potatoes

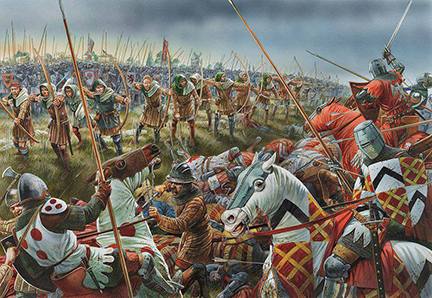

A fortunate tidal crossing of the Somme River gave the English a day’s lead, allowing Edward’s forces time to rest and prepare for battle as they stopped to wait for the far larger French army near the village of Crécy.

A fortunate tidal crossing of the Somme River gave the English a day’s lead, allowing Edward’s forces time to rest and prepare for battle as they stopped to wait for the far larger French army near the village of Crécy.

You must be logged in to post a comment.