We heard a lot this past election, about “Left” and “Right”, “Liberal” and “Conservative”.

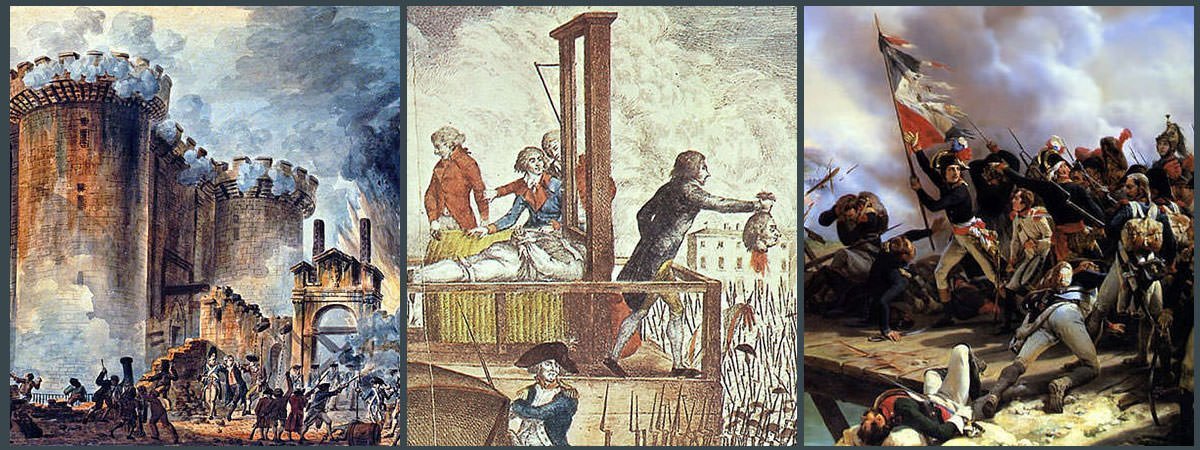

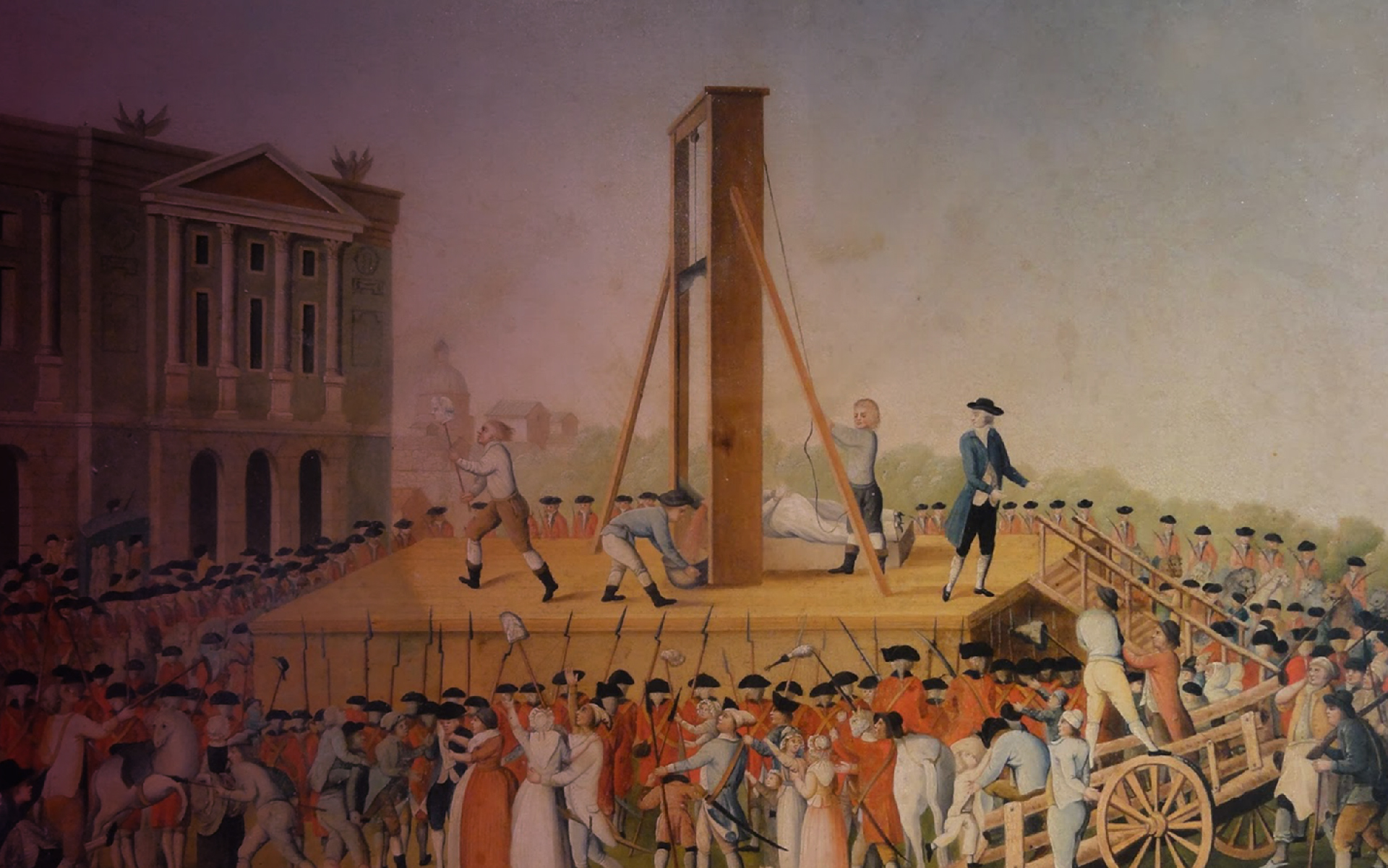

The terms have been with us a long time, originating in the early days of the French Revolution. In those days, National Assembly members supportive of the Monarchy sat on the President’s right. Those favoring the Revolution, on the left. The right side of the seating arrangement began to thin out and disappeared altogether during the “Reign of Terror”, but re-formed with the restoration of the Monarchy, in 1814-1815. By this time, it wasn’t just the “Party of Order” on the right and the “Party of Movement” on the left. Now the terms began to describe nuances in political philosophy, as well.

100 years later, differences between the French left and right of the period, would be recognizable to American political observers of today.

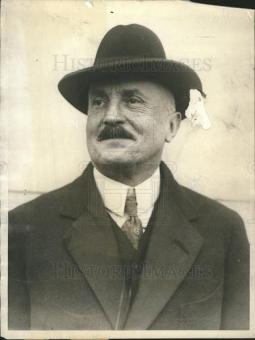

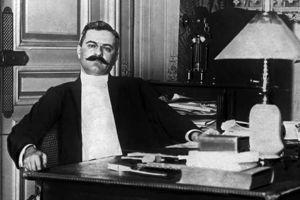

Joseph Cailloux (rhymes with “bayou”) was a left wing politician, appointed prime minister of France in 1911. The man was indiscreet in his love life, even for a French politician. Back in 1907, Cailloux paraded about with a succession of mistresses, finally carrying on with one Henriette Raynouard, while both were married to someone else. They were both divorced by 1911 and that October, Henriette Raynouard became the second, Mrs Cailloux.

The right considered Cailloux to be far too accommodating with Germany, with whom many believed war to be all but inevitable. While serving under the administration of President Raymond Poincare in 1913, Cailloux became a vocal opponent of a bill to increase the length of mandatory military service from two years to three, intended to offset the French population disadvantage between France’s 40 million and Germany’s 70 million.

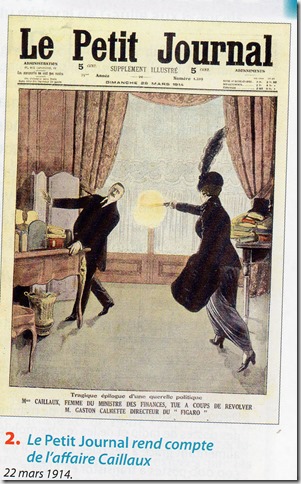

Gaston Calmette, editor of the leading Conservative newspaper Le Figaro, threatened to publicize love letters between the former Prime Minister and his second wife, written while both were still married for the first time.

Henriette Cailloux was not amused.

On March 16, 1914, Madame Cailloux took a taxi to the offices of Le Figaro. After being shown into Calmette’s office, the pair spoke only briefly, before Henriette withdrew the Browning .32 automatic, and fired six rounds at the editor. Two missed, but four were more than enough to do the job. Gaston Calmette was dead within six hours.

German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck once said the next great European war would start with “some damn fool thing in the Balkans”. No one realized it at the time, but Bismarck got his damn fool thing on June 28, 1914, when a Serbian Nationalist assassinated the heir apparent to the Austro-Hungarian throne.

The July Crisis was a series of diplomatic mis-steps, culminating in the ultimatum from Austria-Hungary to the Kingdom of Serbia. Vienna, with tacit support from Berlin, made plans to punish Serbia for her role in the assassination, even as Russia mobilized armies in support of her Slavic ally.

Meanwhile, England and France looked the other way. In Great Britain, officialdom was focused on yet another home rule crisis concerning Ireland, while all of France was distracted by the “Trial of the Century”.

Think of the OJ trial, only in this case the killer was a former First Lady. This one had everything: Left vs. Right, the fall of the powerful, and all the salacious details anyone could ask for. Most of France was riveted by the Caillaux affair in July 1914, ignorant of the European crisis barreling down on them like the four horsemen of the apocalypse. Madame Caillaux’s trial for the murder of Gaston Calmette began on July 20.

She was acquitted on July 28, the jury ruling the murder to be a “crime passionnel”. A crime of passion. That same day, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia.

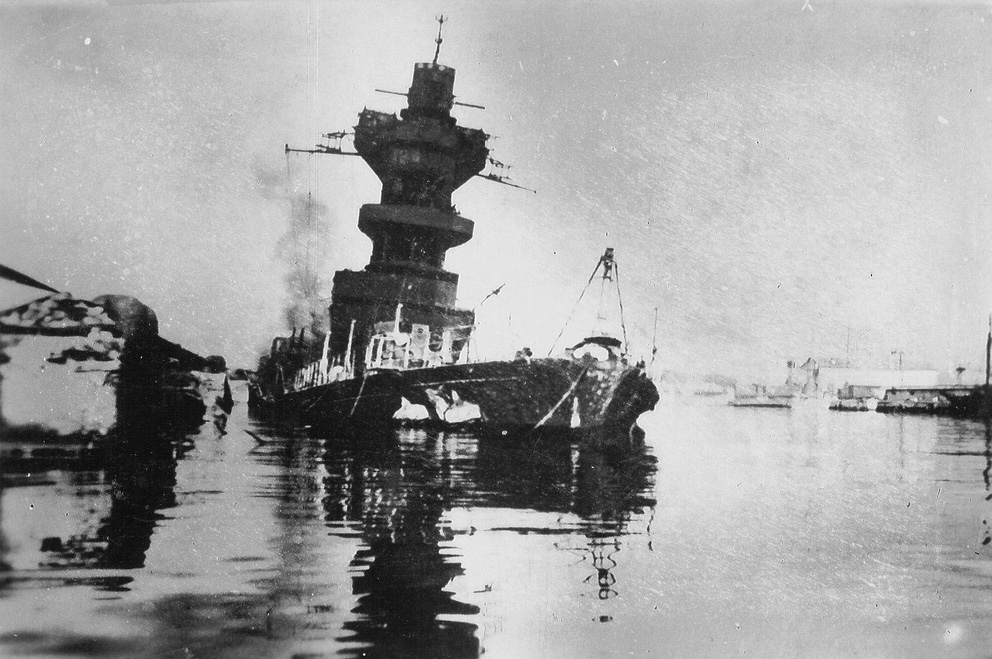

In the days that followed, the Czar would begin the mobilization of men and machines which would place Imperial Russia on a war footing. Imperial Germany invaded Belgium, in pursuit of the one-two punch strategy by which military planners sought first to defeat France, before turning to face the “Russian Steamroller”. England declared war in support of a 75-year old commitment to protect Belgian neutrality, a treaty obligation German diplomats dismissed as a “scrap of paper”.

Eleven million military service members and seven million civilians who were there in July 1914, wouldn’t be alive to see November 11, 1918.

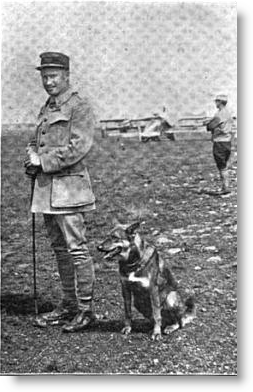

A female lion, “Soda”, was purchased sometime later. The lions were destined to spend their adult years in a Paris zoo but both remembered from whence they had come. Both animals recognized William Thaw on a later visit to the zoo, rolling onto their backs in expectation of a good belly rub.

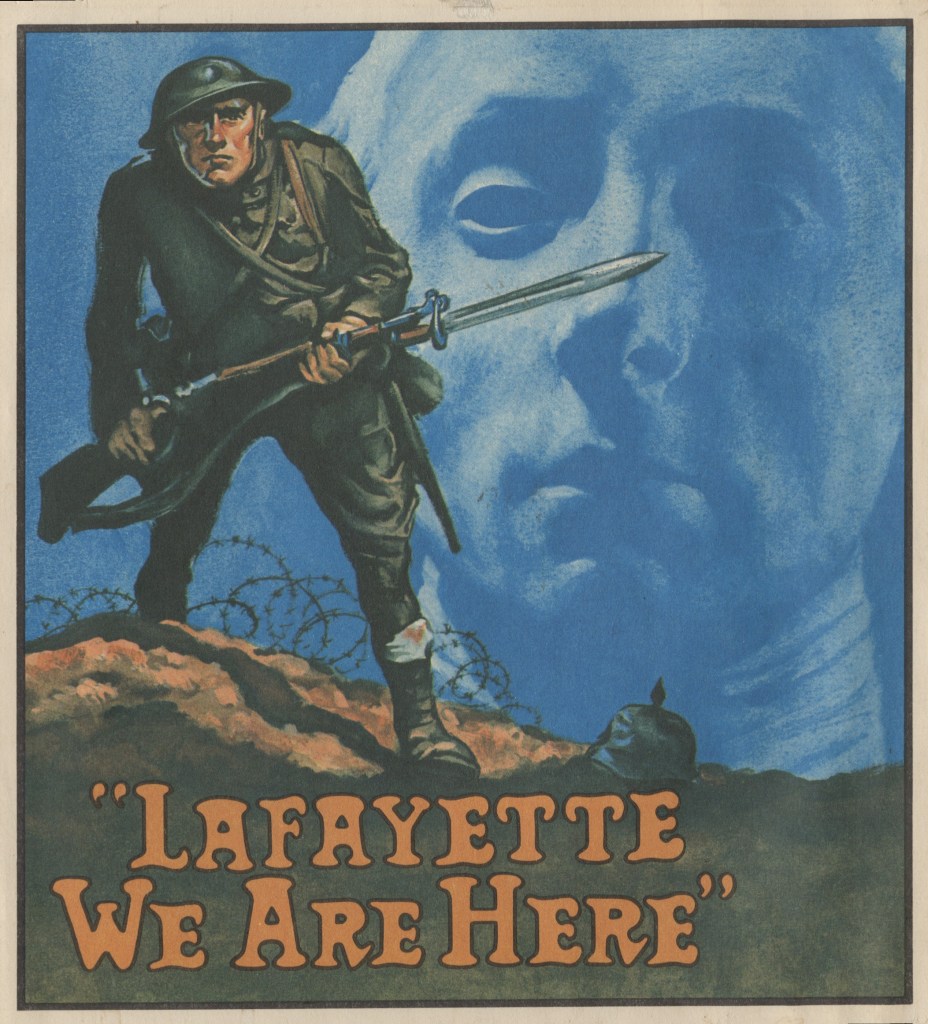

A female lion, “Soda”, was purchased sometime later. The lions were destined to spend their adult years in a Paris zoo but both remembered from whence they had come. Both animals recognized William Thaw on a later visit to the zoo, rolling onto their backs in expectation of a good belly rub. Escadrille N.124 changed its name in December 1916, adopting that of a French hero of the American Revolution. Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette.

Escadrille N.124 changed its name in December 1916, adopting that of a French hero of the American Revolution. Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette.

Those first ten years of independence was a time of increasing unrest for the American’s French ally, of the late revolution. The famous

Those first ten years of independence was a time of increasing unrest for the American’s French ally, of the late revolution. The famous

Napoleon Bonaparte, crowned Emperor the following year, would fight (and win) more battles than Julius Caesar, Hannibal, Alexander the Great and Frederick the Great, combined.

Napoleon Bonaparte, crowned Emperor the following year, would fight (and win) more battles than Julius Caesar, Hannibal, Alexander the Great and Frederick the Great, combined. Jean-Simon Chaudron founded the Abeille Américaine in 1815 (The American Bee), Philadelphia’s leading French language newspaper. Himself a refugee of Santo Domingo (Saint-Domingue), Chaudron catered to French merchants, emigres and former military figures of the Napoleonic era and the Haitian revolution.

Jean-Simon Chaudron founded the Abeille Américaine in 1815 (The American Bee), Philadelphia’s leading French language newspaper. Himself a refugee of Santo Domingo (Saint-Domingue), Chaudron catered to French merchants, emigres and former military figures of the Napoleonic era and the Haitian revolution. In January 1817, the Society for the Vine and Olive selected a site near the Tombigbee and Black Warrior Rivers in west-central Alabama, on former Choctaw lands. On March 3, 1817, Congress passed an act “disposing of a tract of land to embrace four townships, on favorable terms to the emigrants, to enable them successfully to introduce the cultivation of the vine and olive.”

In January 1817, the Society for the Vine and Olive selected a site near the Tombigbee and Black Warrior Rivers in west-central Alabama, on former Choctaw lands. On March 3, 1817, Congress passed an act “disposing of a tract of land to embrace four townships, on favorable terms to the emigrants, to enable them successfully to introduce the cultivation of the vine and olive.” General Charles Lallemand, who joined the French army in 1791, replaced Lefebvre-Desnouettes as President of the Colonial Society. A man better suited to the life of an adventurer than that of the plow, Lallemand was more interested in the wars of Latin American independence, than grapes and olives. By the fall of 1817, Lallemand and 69 loyalists had concocted a plan to sell the land they hadn’t yet paid for, to raise funds for the invasion of Texas.

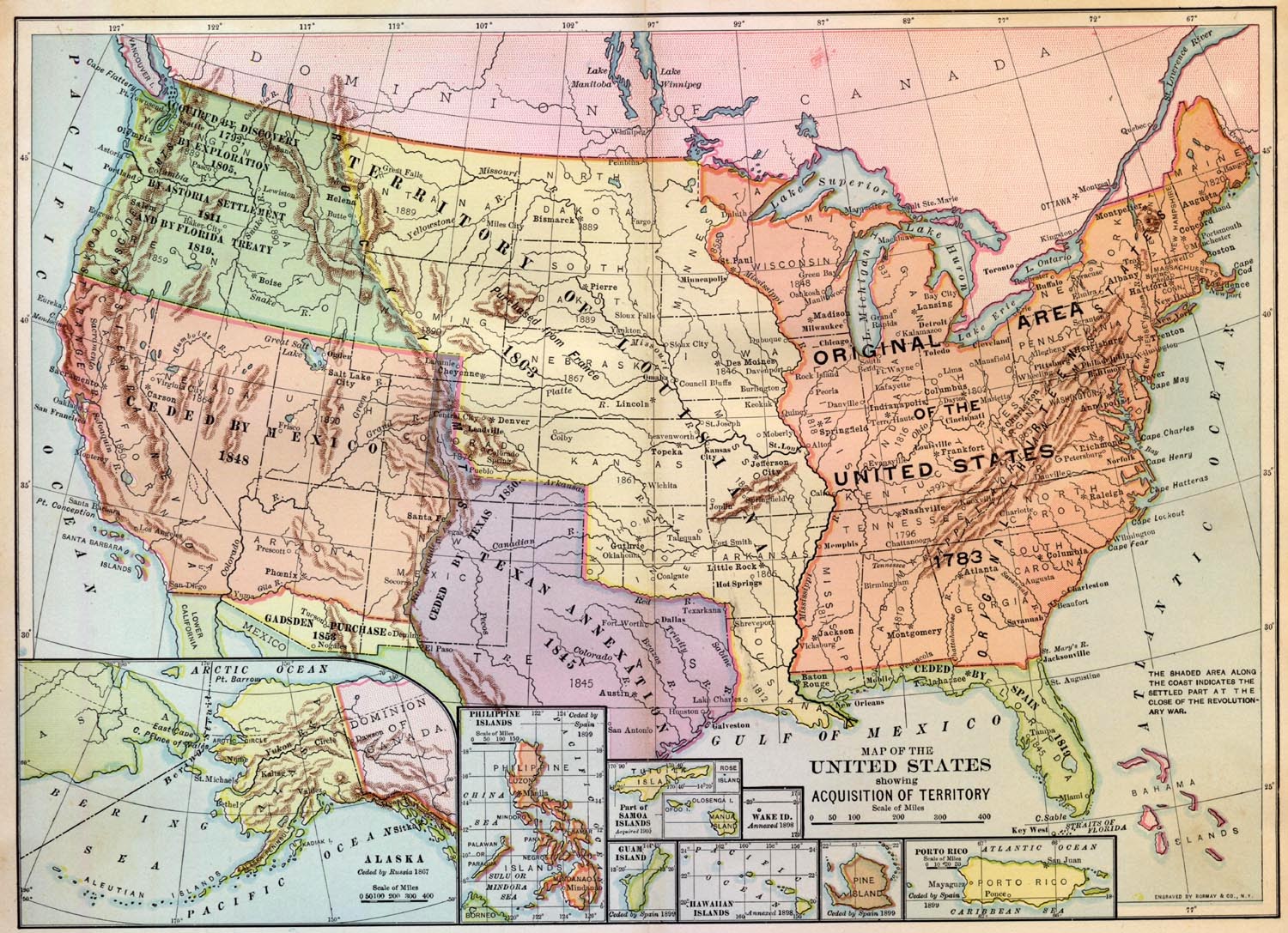

General Charles Lallemand, who joined the French army in 1791, replaced Lefebvre-Desnouettes as President of the Colonial Society. A man better suited to the life of an adventurer than that of the plow, Lallemand was more interested in the wars of Latin American independence, than grapes and olives. By the fall of 1817, Lallemand and 69 loyalists had concocted a plan to sell the land they hadn’t yet paid for, to raise funds for the invasion of Texas. Little is left of the Vine and Olive Colony but the French Emperor lives on, in western Alabama. Marengo County commemorates Napoleon’s June 14, 1800 victory over Austrian forces at the Battle of Marengo. The county seat, also known as Marengo, was later renamed Linden. Shortened from the Napoleonic victory over Bavarian forces led by Archduke John of Austria, at the 1800 battle of Hohenlinden.

Little is left of the Vine and Olive Colony but the French Emperor lives on, in western Alabama. Marengo County commemorates Napoleon’s June 14, 1800 victory over Austrian forces at the Battle of Marengo. The county seat, also known as Marengo, was later renamed Linden. Shortened from the Napoleonic victory over Bavarian forces led by Archduke John of Austria, at the 1800 battle of Hohenlinden.

The oath itself was a revolutionary act. Unlike the English Parliament, the Estates-General were little more than an advisory body, whose authority was not required for Royal taxation or legislative initiatives. The oath taken that day asserted that political authority came from the people and their representatives, not from the monarchy. The National Assembly had declared itself supreme in the exercise of state power, making it increasingly difficult for the monarchy to operate based on “Divine Right of Kings”.

The oath itself was a revolutionary act. Unlike the English Parliament, the Estates-General were little more than an advisory body, whose authority was not required for Royal taxation or legislative initiatives. The oath taken that day asserted that political authority came from the people and their representatives, not from the monarchy. The National Assembly had declared itself supreme in the exercise of state power, making it increasingly difficult for the monarchy to operate based on “Divine Right of Kings”.

The monarchical powers of Europe were quick to intervene. For the 32nd time since the Norman invasion of 1066, England and France once again found themselves in a state of war.

The monarchical powers of Europe were quick to intervene. For the 32nd time since the Norman invasion of 1066, England and France once again found themselves in a state of war.

Jean Le Maistre, whose presence as Vice-Inquisitor for Rouen was required by canon law, objected to the proceedings and refused to appear, until the English threatened his life.

Jean Le Maistre, whose presence as Vice-Inquisitor for Rouen was required by canon law, objected to the proceedings and refused to appear, until the English threatened his life. The death sentence was carried out on May 30, 1431, in the old marketplace at Rouen. She was 19.

The death sentence was carried out on May 30, 1431, in the old marketplace at Rouen. She was 19.

You must be logged in to post a comment.