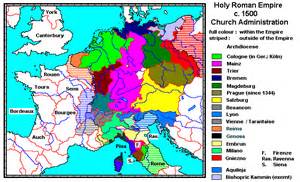

Alliances came and went throughout 18th century Europe, and treaties were often sealed by arranged marriages. One such alliance took place in 1770 when Francis I, Holy Roman Emperor and his wife Maria Theresa, the formidable Queen of Hungary and Bohemia, married their daughter Maria Antonia to Louis-Auguste, the son of Louis XV, King of France.

The happy couple had yet to meet when the marriage was performed by proxy, the bride remaining in Vienna while the groom stayed in Paris. At 12 she was now the Dauphine, Marie Antoinette, wife of the 14-year-old Dauphin, future King of France.

There was a second, ceremonial wedding held in May, after which came the ritual bedding. This wasn’t the couple quietly retiring to their own private space. This was the bizarre spectacle of a room full of courtiers, peering down at the proceedings, to make sure the marriage was consummated.

There was a second, ceremonial wedding held in May, after which came the ritual bedding. This wasn’t the couple quietly retiring to their own private space. This was the bizarre spectacle of a room full of courtiers, peering down at the proceedings, to make sure the marriage was consummated.

It was not, and that failure did damage to both of their reputations.

The people liked their new Dauphine at first, but the Royal Court was another story. They had promoted several Saxon Princesses for the match, and called Marie Antoinette “The Austrian Woman”. She would be called far worse.

The stories you read about 18th century Court intrigue make you wonder how anyone lived like that. Antoinette was naive of the shark tank into which she’d been thrown. Relations were especially difficult with the King’s mistress, the Comtesse du Barry, and Antoinette was somehow expected to work them out. The King’s daughters, on the other hand, didn’t care for du Barry’s unsavory relations with their father. Antoinette couldn’t win. The sisters complained of feeling “betrayed” one time, when Antoinette commented to the King’s mistress “There are a lot of people at Versailles today”.

Court intrigues were accompanied by reports to Antoinette’s mother in Vienna, the Empress responding with her own stream of criticism. The Dauphin was more interested in lock making and hunting, she wrote, because Antoinette had failed to “inspire passion” in her husband. The Empress even went so far as to tell her daughter that she was no longer pretty. She had lost her grace. Antoinette came to fear her own mother more than she loved her.

Louis-Auguste was crowned Louis XVI, King of France, on June 11, 1775. Antoinette remained by his side, though she was never crowned Queen, instead remaining Louis’ “Queen Consort”.

Louis-Auguste was crowned Louis XVI, King of France, on June 11, 1775. Antoinette remained by his side, though she was never crowned Queen, instead remaining Louis’ “Queen Consort”.

With her marriage as yet unconsummated, Antoinette’s position became precarious when her sister in law gave birth to a son and possible heir to the throne. Antoinette spent her time gambling and shopping, while wild rumors and printed pamphlets described her supposedly bizarre sexual romps.

France had serious debt problems in the 1770s, the result of endless foreign wars, but Antoinette received more than her share of the blame. As first lady to the French court, Antoinette was expected to be a fashion trendsetter. Her shopping was in keeping with the role, but rumors wildly inflated her spending habits. Her lady-in-waiting protested that her habits were modest, visiting village workshops in a simple dress and straw hat. Nevertheless, Antoinette was rumored to have plastered the walls of Versailles with gold and diamonds.

The difficult winter of 1788-89 produced bread shortages and rising prices as the King withdrew from public life. The marriage had produced children by this time, but the legend of the licentious spendthrift and empty headed foreign queen took root in French mythology, as government debt overwhelmed the economy.

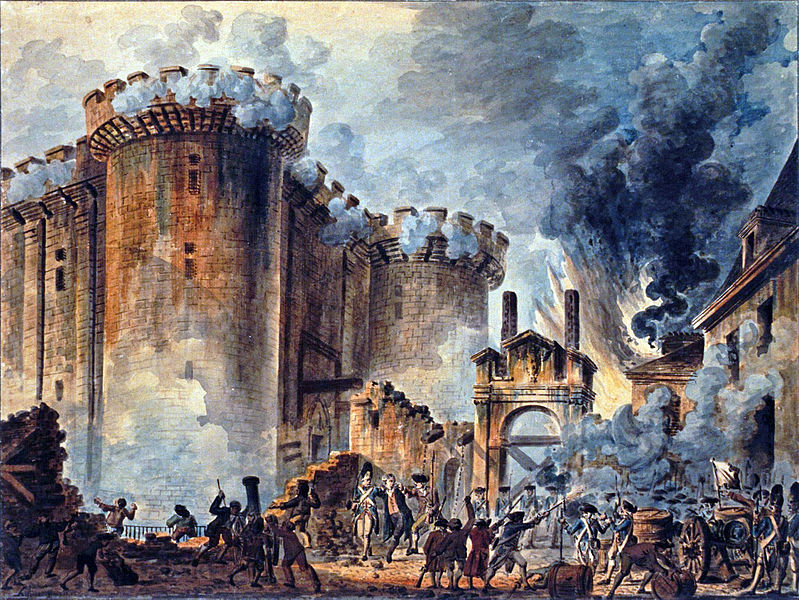

French politics boiled over in June 1789, leading to the storming of the Bastille on July 14. Much of the French nobility fled as the newly formed National Constituent Assembly conscripted men to serve in the Garde Nationale, while the French Constitution of 1791 weakened the King’s authority.

Food shortages magnified the unrest. In October, the King and Queen were placed under house arrest in the Tuileries Palace. In June they attempted to flee the escalating violence, but were caught and returned within days. Radical Jacobins exploited the escape attempt as a betrayal, and pushed to have the monarchy abolished altogether.

Unrest turned to barbarity as Antoinette’s friend and supporter, the Princesse de Lamballe, was taken by the Paris Commune for interrogation. She was murdered at La Force prison, her head fixed on a pike and marched through the city.

Unrest turned to barbarity as Antoinette’s friend and supporter, the Princesse de Lamballe, was taken by the Paris Commune for interrogation. She was murdered at La Force prison, her head fixed on a pike and marched through the city.

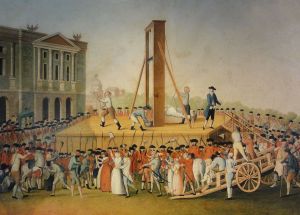

Louis XVI was charged with undermining the First Republic in December 1792, found guilty and executed by guillotine on January 21, 1793. He was 38.

Marie-Antoinette became prisoner #280, her health deteriorating in the following months. She suffered from tuberculosis by this time and was frequently bleeding, possibly from uterine cancer.

Antoinette was taken from her cell on October 14, subjected to a sham trial whose outcome was never in doubt. She was accused of molesting her own son, a charge so outrageous that even the market women who had stormed the palace demanding her entrails in 1789, spoke in her support. “If I have not replied”, she said, “it is because nature itself refuses to respond to such a charge laid against a mother.”

Marie-Antoinette’s hair was cut off on October 16, 1793. She was driven through Paris in an ox cart, taken to the Place de la Révolution, and decapitated. She accidentally stepped on the executioner’s foot on mounting the scaffold. Her last words were “Pardon me sir, I meant not to do it”.

Marie-Antoinette’s hair was cut off on October 16, 1793. She was driven through Paris in an ox cart, taken to the Place de la Révolution, and decapitated. She accidentally stepped on the executioner’s foot on mounting the scaffold. Her last words were “Pardon me sir, I meant not to do it”.

“Let them eat cake” is often attributed to Marie Antoinette, but there’s no evidence that she ever said it. The phrase appears in the autobiography of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, “Les Confessions”, attributed to a “Grande Princesse” whom the book declines to name. Considering the lifetime of cheap and mean-spirited gossip to which Marie Antoinette was subjected, it’s easy to believe that this was more of the same.

Charlemagne led an incursion into Muslim Spain, continuing his father’s policy toward the Church when he cleared the Lombards out of Northern Italy. He Christianized the Saxon tribes to his east, sometimes under pain of death.

Charlemagne led an incursion into Muslim Spain, continuing his father’s policy toward the Church when he cleared the Lombards out of Northern Italy. He Christianized the Saxon tribes to his east, sometimes under pain of death.

Germany needed air supremacy before “Operation Sea Lion”, the amphibious invasion of England, could begin. Luftwaffe commander Hermann Göring said he would have it in four days.

Germany needed air supremacy before “Operation Sea Lion”, the amphibious invasion of England, could begin. Luftwaffe commander Hermann Göring said he would have it in four days.

Czechoslovakia fell to the Nazis on the Ides of March, 1939, Czech armed forces having been ordered to offer no resistance. Some 4,000 Czech soldiers and airmen managed to get out, most escaping to neighboring Poland.

Czechoslovakia fell to the Nazis on the Ides of March, 1939, Czech armed forces having been ordered to offer no resistance. Some 4,000 Czech soldiers and airmen managed to get out, most escaping to neighboring Poland.

British military authorities were slow to recognize the flying skills of the Polskie Siły Powietrzne (Polish Air Forces), the first fighter squadrons only seeing action in the third phase of the Battle of Britain. Despite the late start, Polish flying skills proved superior to those of less-experienced Commonwealth pilots. The 303rd Polish fighter squadron became the most successful RAF fighter unit of the period, its most prolific flying ace being Czech Sergeant Josef František. He was killed in action in the last phase of the Battle of Britain, the day after his 26th birthday.

British military authorities were slow to recognize the flying skills of the Polskie Siły Powietrzne (Polish Air Forces), the first fighter squadrons only seeing action in the third phase of the Battle of Britain. Despite the late start, Polish flying skills proved superior to those of less-experienced Commonwealth pilots. The 303rd Polish fighter squadron became the most successful RAF fighter unit of the period, its most prolific flying ace being Czech Sergeant Josef František. He was killed in action in the last phase of the Battle of Britain, the day after his 26th birthday.

the nearby town of Chartres under siege. Normans had burned the place to the ground back in 858 and would probably have done so again, but for their defeat at the battle of Chartres on July 20.

the nearby town of Chartres under siege. Normans had burned the place to the ground back in 858 and would probably have done so again, but for their defeat at the battle of Chartres on July 20. The deal made sense for the King, because he had already bankrupted his treasury paying these people tribute. And what better way to deal with future Viking raids down the channel, than to make them the Vikings’ own problem?

The deal made sense for the King, because he had already bankrupted his treasury paying these people tribute. And what better way to deal with future Viking raids down the channel, than to make them the Vikings’ own problem? the symbolic importance of the gesture, but wasn’t about to submit to such degradation himself. The chieftain motioned to one of his lieutenants, a man almost as huge as himself, to kiss the king’s foot. The man shrugged, reached down and lifted King Charles off the ground by his ankle. He kissed the foot, and tossed the King of the Franks aside. Like a sack of potatoes

the symbolic importance of the gesture, but wasn’t about to submit to such degradation himself. The chieftain motioned to one of his lieutenants, a man almost as huge as himself, to kiss the king’s foot. The man shrugged, reached down and lifted King Charles off the ground by his ankle. He kissed the foot, and tossed the King of the Franks aside. Like a sack of potatoes

The Mel Gibson film “Braveheart” has it mostly right as it depicts Wallace’s betrayal by Scottish Nobles. Wallace had evaded capture until August 5, 1305, when a Scottish knight loyal to Edward, John de Menteith, turned him over to English soldiers at Robroyston, near Glasgow.

The Mel Gibson film “Braveheart” has it mostly right as it depicts Wallace’s betrayal by Scottish Nobles. Wallace had evaded capture until August 5, 1305, when a Scottish knight loyal to Edward, John de Menteith, turned him over to English soldiers at Robroyston, near Glasgow.

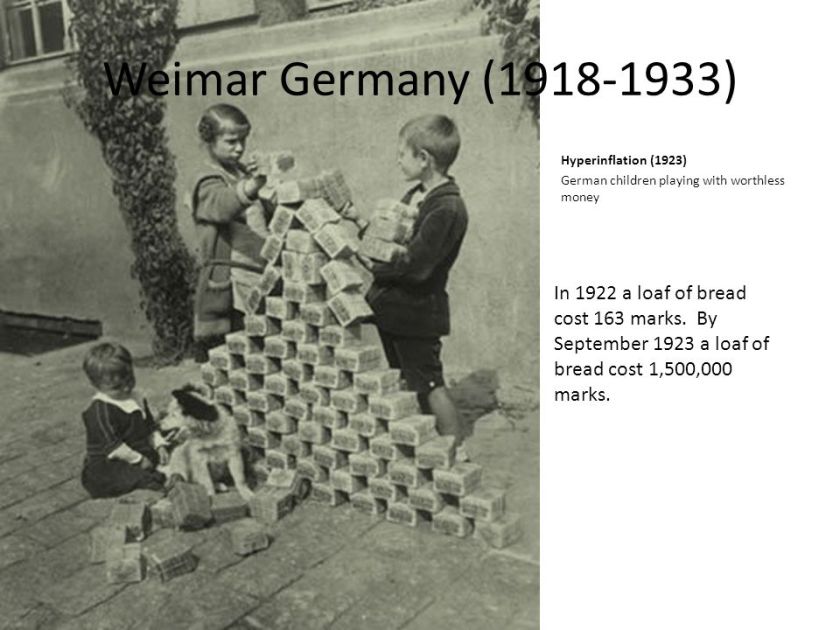

Hungary replaced the Kronen with the Pengö in 1926, pegged to a rate of 12,500 to one.

Hungary replaced the Kronen with the Pengö in 1926, pegged to a rate of 12,500 to one.

One more currency replacement and all that Keynesian largesse would finally stabilize the currency, but at what cost? Real wages were reduced by 80% and creditors wiped out. The fate of the nation was sealed when communists seized power in 1949. Hungarians could now share in that old Soviet joke: “They pretend to pay us, and we pretend to work”.

One more currency replacement and all that Keynesian largesse would finally stabilize the currency, but at what cost? Real wages were reduced by 80% and creditors wiped out. The fate of the nation was sealed when communists seized power in 1949. Hungarians could now share in that old Soviet joke: “They pretend to pay us, and we pretend to work”.

Finally there was no choice for the Grand Armée, but to turn about and go home. Starving and exhausted with no winter clothing, stragglers were frozen in place or picked off by villagers or pursuing Cossacks. From Moscow to the frontiers you could follow their retreat, by the bodies they left in the snow. 685,000 had crossed the Neman River on June 24. By mid-December there were fewer than 70,000 known survivors.

Finally there was no choice for the Grand Armée, but to turn about and go home. Starving and exhausted with no winter clothing, stragglers were frozen in place or picked off by villagers or pursuing Cossacks. From Moscow to the frontiers you could follow their retreat, by the bodies they left in the snow. 685,000 had crossed the Neman River on June 24. By mid-December there were fewer than 70,000 known survivors. The Congress of Vienna declared Napoleon an outlaw on March 13, 1815. Austria, Prussia, Russia and the UK bound themselves to put 150,000 men apiece into the field to end his rule.

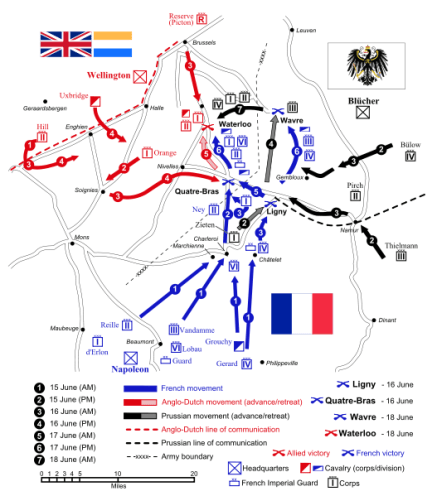

The Congress of Vienna declared Napoleon an outlaw on March 13, 1815. Austria, Prussia, Russia and the UK bound themselves to put 150,000 men apiece into the field to end his rule.

Most of the political and military establishment lined up against Dreyfus, but the public outcry became furious after writer Émile Zola published his vehement open letter “J’accuse” (I accuse) in the Paris press in January 1898.

Most of the political and military establishment lined up against Dreyfus, but the public outcry became furious after writer Émile Zola published his vehement open letter “J’accuse” (I accuse) in the Paris press in January 1898.

In May of 1940 the British Expeditionary Force and what remained of French forces occupied a sliver of land along the English Channel. Field Marshall Gerd von Rundstedt called a halt of the German armored advance on May 24, while Hermann Göring urged Hitler to stop the ground assault, let the Luftwaffe finish the destruction of Allied forces. On the other side of the channel, Admiralty officials combed every boatyard they could find for boats to ferry their people off of the beach.

In May of 1940 the British Expeditionary Force and what remained of French forces occupied a sliver of land along the English Channel. Field Marshall Gerd von Rundstedt called a halt of the German armored advance on May 24, while Hermann Göring urged Hitler to stop the ground assault, let the Luftwaffe finish the destruction of Allied forces. On the other side of the channel, Admiralty officials combed every boatyard they could find for boats to ferry their people off of the beach.

You must be logged in to post a comment.