The history of dogs in war is as old as history itself. The dogs of King Alyattes of Lydia killed many of his Cimmerian adversaries and routed the rest around 600BC, permanently driving the invader from Asia Minor in the earliest known use of war dogs in battle.

The Molossians of Epirus, descended from King Molossus, grandson of the mighty Achilles according to Greek mythology, used large, powerfully built dogs specifically trained for battle. Today, “molosser” describes a body type more than any specific breed. Modern molossers include the Mastiff, Bernese Mountain Dog, Newfoundland and Saint Bernard.

Ancient Greeks, Romans and Egyptians used dogs as sentries or on patrol. In late antiquity, Xerxes I, the Persian King who faced the Spartan King Leonidas across the pass at Thermopylae, was accompanied by a pack of Indian hounds.

Attila the Hun went to war with a pack of hounds, as did the Spanish Conquistadors of the 1500s.

The Staffordshire Bull Terrier Sallie “joined up” in 1861, serving throughout the Civil War with the 11th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. At Cedar Mountain, Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, and Spotsylvania, Sallie’d take her position along with the colors, barking ferociously at the adversary.

Abraham Lincoln spotted Sallie once from a reviewing stand, and tipped his hat.

Sallie was killed at Hatcher’s Run in February, 1865. Several of “her” men laid down their arms and buried her then and there, despite being under Confederate fire.

Dogs performed a variety of roles in WWI, from ratters in the trenches, to sentries, scouts and runners. “Mercy” dogs were trained to seek out the wounded on battlefields, carrying medical supplies with which the stricken could treat themselves.

![DOG 19 [1600x1200] (4).jpg.opt897x579o0,0s897x579](https://todayinhistory.blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/dog-19-1600x1200-4-opt897x579o00s897x579.jpg?w=840)

By the end of the “Great War”, France, Great Britain and Belgium had at least 20,000 dogs on the battlefield, Imperial Germany over 30,000. Some sources report that over a million dogs served over the course of the war.

The famous Rin Tin Tin canine movie star of the 1920s was rescued as a puppy, from the bombed out remains of a German Army kennel, in 1917.

In the spring of 1918, GHQ of the American Expeditionary Force recommended using dogs as sentries, messengers and draft animals, however the war was over before US forces put together any kind of a War Dog program.

America’s first war dog, “Sgt. Stubby”, went “Over There” by accident, serving 18 months on the Western Front before coming home to a well-earned retirement.

On March 13, 1942, the Quartermaster Corps began training dogs for the US Army “K-9 Corps.” In the beginning, the owners of healthy dogs were encouraged to “loan” their dogs to the Quartermaster Corps, where they were trained for service with the Army, Navy, Marine Corps and Coast Guard.

The program initially accepted over 30 breeds of dog, but the list soon narrowed to German Shepherds, Belgian Sheep Dogs, Doberman Pinschers, Collies, Siberian Huskies, Malamutes and Eskimo Dogs.

WWII-era Military Working Dogs (MWDs) served on sentry, scout and patrol missions, in addition to performing messenger and mine-detection work. The keen senses of scout dogs saved countless lives, by alerting to the approach of enemy forces, incoming fire, and hidden booby traps & mines.

The most famous MWD of WWII was “Chips“, a German Shepherd/Husky mix assigned to the 3rd Infantry Division in Italy. Trained as a sentry dog, Chips broke away from his handler and attacked an enemy machine gun nest. Wounded in the process, his singed fur demonstrated the point-blank fire with which the enemy fought back. To no avail. Chips single-handedly forced the surrender of the entire gun crew.

Chips was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, Silver Star and Purple Heart, the honors later revoked due to an Army policy against the commendation of animals. It makes me wonder if the author of such a policy ever saw service beyond his own desk.

Smoky, the littlest war dog, once ran a communication wire through a small culvert in Lingayen Gulf, Luzon, a task which would have otherwise taken an airstrip out of service for three days, and exposed an entire construction battalion to enemy fire.

Of the 549 dogs who returned from service in WWII, all but four were able to return to civilian life.

Over 500 dogs died on the battlefields of Vietnam, of injuries, illnesses, and combat wounds. 10,000 servicemen served as dog handlers during the war, with an estimated 4,000 Military Working Dogs. 261 handlers paid the ultimate price. K9 units are estimated to have saved over 10,000 human lives.

It’s only a guess but, having a handler and a retired MWD in the family, I believe I’m right: hell would freeze before any handler walked away from his dog. The military bureaucracy, is another matter. The vast majority of MWDs were left behind during the Vietnam era. Only about 200 dogs survived the war to be assigned to other bases. The remaining dogs were either euthanized or left behind as “surplus equipment”.

Today there are about 2,500 dogs in active service. Approximately 700 deployed overseas. The American Humane Association estimates that each MWD saves an average 150-200 human lives over the course of its career.

In 2015, Congressman Frank LoBiondo (R-NJ) and Senator Claire McCaskill (D-MO) introduced language in their respective bodies, mandating that MWDs be returned to American soil upon retirement, and that their handlers and/or handlers’ families be given first right of adoption.

LoBiondo’s & McCaskill’s language became law on November 25, when the President signed the 2016 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA). It’s a small step in recognizing what we owe to those who have stepped up in defense of our nation, both two-legged and four.

London’s teaching hospitals at first explored quiet means of taking down what they regarded as an insult to the profession. By November, medical students were crossing the Thames with sledge hammers and crow bars, intending to take matters into their own hands.

London’s teaching hospitals at first explored quiet means of taking down what they regarded as an insult to the profession. By November, medical students were crossing the Thames with sledge hammers and crow bars, intending to take matters into their own hands. Seventy-five years would come and go, before a new Brown Dog memorial was commissioned by the National Anti-Vivisection Society and the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection.

Seventy-five years would come and go, before a new Brown Dog memorial was commissioned by the National Anti-Vivisection Society and the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection.

On March 1, 2011, L/Cpl Tasker was killed by a Taliban sniper while on patrol in Helmand Province, and brought back to base by his fellow soldiers. Theo suffered a seizure after returning to base and never recovered. He died that afternoon. It was believed that Theo’s seizure was brought on by the stresses of Tasker’s death, but the autopsy proved inconclusive. Liam’s mother Jane Duffy later said, “I think Theo died of a broken heart, nobody will convince me any different.”

On March 1, 2011, L/Cpl Tasker was killed by a Taliban sniper while on patrol in Helmand Province, and brought back to base by his fellow soldiers. Theo suffered a seizure after returning to base and never recovered. He died that afternoon. It was believed that Theo’s seizure was brought on by the stresses of Tasker’s death, but the autopsy proved inconclusive. Liam’s mother Jane Duffy later said, “I think Theo died of a broken heart, nobody will convince me any different.” On a more upbeat note, and this story needs one, our daughter Carolyn and son-in-law Nate transferred to Savannah in 2013, where Nate deployed to the Wardak province of Afghanistan as a TEDD handler and paired with “MWD Zino”, a four-year-old German Shepherd trained to detect up to 64 explosive compounds.

On a more upbeat note, and this story needs one, our daughter Carolyn and son-in-law Nate transferred to Savannah in 2013, where Nate deployed to the Wardak province of Afghanistan as a TEDD handler and paired with “MWD Zino”, a four-year-old German Shepherd trained to detect up to 64 explosive compounds.

Parisian children made little good luck charms, as “protection” from the Paris gun. They were tiny pairs of handmade dolls, joined together by scraps of yarn. Their names were Nénette and Rintintin

Parisian children made little good luck charms, as “protection” from the Paris gun. They were tiny pairs of handmade dolls, joined together by scraps of yarn. Their names were Nénette and Rintintin US Army Air Service Corporal Lee Duncan was in Paris at this time, with the 135th Aero Squadron. Duncan was aware of the custom, he may even have been given such a talisman himself.

US Army Air Service Corporal Lee Duncan was in Paris at this time, with the 135th Aero Squadron. Duncan was aware of the custom, he may even have been given such a talisman himself.

Better known as “Strongheart”, Etzel appeared in silent films throughout the ’20s, becoming the first major canine film star and credited with enormously increasing the popularity of the breed.

Better known as “Strongheart”, Etzel appeared in silent films throughout the ’20s, becoming the first major canine film star and credited with enormously increasing the popularity of the breed.

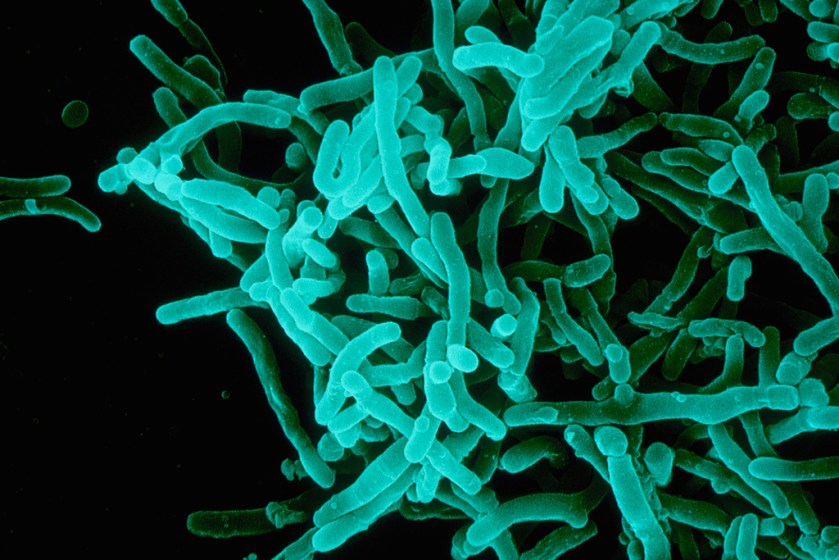

Dr. Curtis Welch practiced medicine in Nome, Alaska, in 1925. Several children became ill with what he first diagnosed as tonsillitis. More came down with sore throats, early sufferers beginning to die as Welch observed the pseudomembrane of diphtheria. He had ordered fresh antitoxin the year before, but the shipment hadn’t arrived by the time the ports froze over. By January, all the serum in Nome was expired.

Dr. Curtis Welch practiced medicine in Nome, Alaska, in 1925. Several children became ill with what he first diagnosed as tonsillitis. More came down with sore throats, early sufferers beginning to die as Welch observed the pseudomembrane of diphtheria. He had ordered fresh antitoxin the year before, but the shipment hadn’t arrived by the time the ports froze over. By January, all the serum in Nome was expired.

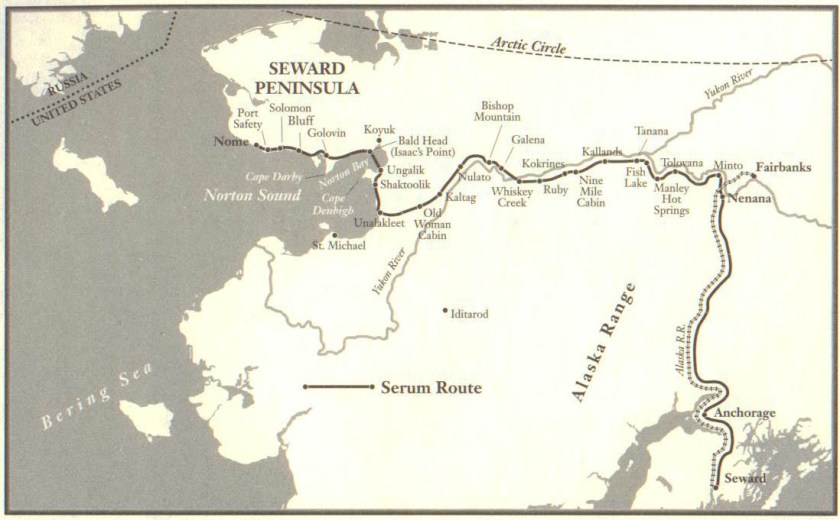

20 mushers and 150 dogs or more had covered 674 miles in 5 days, 7½ hours, a distance that normally took the mail relay 2-3 weeks. Not a single serum ampule was broken.

20 mushers and 150 dogs or more had covered 674 miles in 5 days, 7½ hours, a distance that normally took the mail relay 2-3 weeks. Not a single serum ampule was broken.

Once, the small dog was able to perform a task in minutes that otherwise would have taken an airstrip out of service for three days, and exposed an entire construction battalion to enemy fire. The air field at Lingayen Gulf, Luzon, was crucial to the Allied war effort, and the signal corps needed to run a telegraph wire across the field. A 70′ long, 8” pipe crossed underneath the air strip, half filled with dirt.

Once, the small dog was able to perform a task in minutes that otherwise would have taken an airstrip out of service for three days, and exposed an entire construction battalion to enemy fire. The air field at Lingayen Gulf, Luzon, was crucial to the Allied war effort, and the signal corps needed to run a telegraph wire across the field. A 70′ long, 8” pipe crossed underneath the air strip, half filled with dirt. Smoky toured all over the world after the war, appearing in over 42 television programs and entertaining thousands at veteran’s hospitals. In June 1945, Smoky toured the 120th General Hospital in Manila, visiting with wounded GIs from the Battle of Luzon. She’s considered to be the first therapy dog, and credited with expanding interest in what had hitherto been an obscure breed.

Smoky toured all over the world after the war, appearing in over 42 television programs and entertaining thousands at veteran’s hospitals. In June 1945, Smoky toured the 120th General Hospital in Manila, visiting with wounded GIs from the Battle of Luzon. She’s considered to be the first therapy dog, and credited with expanding interest in what had hitherto been an obscure breed. Bill Wynne was 90 years old in 2012, when he was “flabbergasted” to be approached by Australian authorities. They explained that an Australian army nurse had purchased the dog from a Queen Street pet store, becoming separated in the jungles of New Guinea. 68 years later, the Australians had come to award his dog a medal.

Bill Wynne was 90 years old in 2012, when he was “flabbergasted” to be approached by Australian authorities. They explained that an Australian army nurse had purchased the dog from a Queen Street pet store, becoming separated in the jungles of New Guinea. 68 years later, the Australians had come to award his dog a medal.

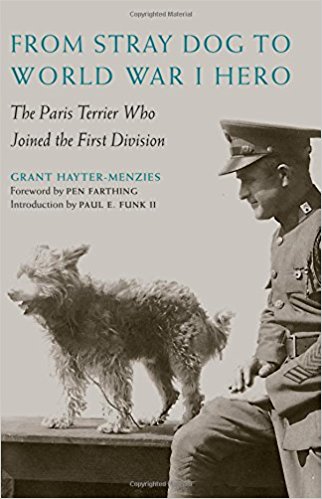

It was a small dog, possibly a Cairn Terrier mix. He looked like a pile of rags, and that’s what they called him. The dog had gotten Donovan out of a jam, now he would become the division mascot for real. Rags was now part of the US 1st Infantry Division, the Big Red One.

It was a small dog, possibly a Cairn Terrier mix. He looked like a pile of rags, and that’s what they called him. The dog had gotten Donovan out of a jam, now he would become the division mascot for real. Rags was now part of the US 1st Infantry Division, the Big Red One.

In 1927, Army Chief of Staff General Charles Summerall directed that a bill be drafted and submitted to Congress, “To revive the Badge of Military Merit”. This badge of merit came to be known as the Purple Heart. General Douglas MacArthur, Summerall’s successor, began work on a new design for the medal in 1931. Elizabeth Will, heraldic specialist with the Quartermaster General’s office, created the design we see today.

In 1927, Army Chief of Staff General Charles Summerall directed that a bill be drafted and submitted to Congress, “To revive the Badge of Military Merit”. This badge of merit came to be known as the Purple Heart. General Douglas MacArthur, Summerall’s successor, began work on a new design for the medal in 1931. Elizabeth Will, heraldic specialist with the Quartermaster General’s office, created the design we see today.

During the landing phase, private Rowell and Chips were pinned down by an Italian machine gun team. The dog broke free from his handler, running across the beach and jumping into the pillbox. Chips attacked the four Italians manning the machine gun, single-handedly forcing their surrender to American troops. The dog sustained a scalp wound and powder burns in the process, demonstrating that they had tried to shoot him during the brawl. In the end, the score was Chips 4, Italians Zero. He helped to capture ten more later that same day.

During the landing phase, private Rowell and Chips were pinned down by an Italian machine gun team. The dog broke free from his handler, running across the beach and jumping into the pillbox. Chips attacked the four Italians manning the machine gun, single-handedly forcing their surrender to American troops. The dog sustained a scalp wound and powder burns in the process, demonstrating that they had tried to shoot him during the brawl. In the end, the score was Chips 4, Italians Zero. He helped to capture ten more later that same day.

Sallie’s first battle came at Cedar Mountain, in 1862. No one thought of sending her to the rear before things got hot, so she took up her position with the colors, barking ferociously at the adversary. There she remained throughout the entire engagement, as she did at Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, and Spotsylvania. They said she only hated three things: Rebels, Democrats, and Women.

Sallie’s first battle came at Cedar Mountain, in 1862. No one thought of sending her to the rear before things got hot, so she took up her position with the colors, barking ferociously at the adversary. There she remained throughout the entire engagement, as she did at Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, and Spotsylvania. They said she only hated three things: Rebels, Democrats, and Women.

“Sallie was a lady,

“Sallie was a lady,

You must be logged in to post a comment.