The wood burning steam locomotive #171 left Jersey City, New Jersey on July 15, 1864, pulling 17 passenger and freight cars. On board were 833 Confederate Prisoners of War and 128 Union guards, heading from Point Lookout prison in Maryland, to the Union prison camp in Elmira, New York.

Engine #171 was an “extra” that day, running behind a scheduled train numbered West #23. West #23 displayed warning flags, giving the second train right of way, but #171 was running late. First delayed while guards located missing prisoners, then there was that interminable wait for the drawbridge. By the time #171 reached Port Jervis, Pennsylvania, the train was four hours behind schedule.

Telegraph operator Douglas “Duff” Kent was on duty at the Lackawaxen Junction station, near Shohola, Pennsylvania. Kent had seen West #23 pass through that morning with the “extra” flags. His job was to hold eastbound traffic at Lackawaxen until the second train passed. Kent may have been drunk that day, but nobody’s certain. He disappeared the following day, never to be seen again.

Erie Engine #237 arrived at Lackawaxen at 2:30 pm pulling 50 coal cars, loaded for Jersey City. Kent gave the all clear at 2:45. The main switch was opened, and Erie #237 joined the single track heading east out of Shohola.

Only four miles of track stood between two speeding, 30-ton steam locomotives.

The trains met head-on at “King and Fuller’s Cut”, a pass blasted out of solid rock and named after its prime engineering contractors. This section of track followed a blind curve with only 50’ visibility. Engineer Samuel Hoitt was at the throttle of #237. Hoitt would survive, having just enough time to jump before the moment of impact. One man in the lead car on #171 was thrown clear. He too would live. There would be no other survivors among the 37 men on that car.

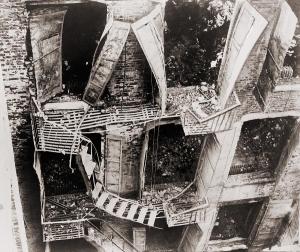

Historian Joseph C. Boyd described what followed on the 100th anniversary of the wreck: “[T]he wooden coaches telescoped into one another, some splitting open and strewing their human contents onto the berm, where flying glass, splintered wood, and jagged metal killed or injured them as they rolled. Other occupants were hurled through windows or pitched to the track as the car floors buckled and opened. The two ruptured engine tenders towered over the wreckage, their massive floor timbers snapped like matchsticks. Driving rods were bent like wire. Wheels and axles lay broken. The troop train’s forward boxcar had been compacted and within the remaining mass were the remains of 37 men”. Witnesses saw “headless trunks, mangled between the telescoped cars” and “bodies impaled on iron rods and splintered beams.”

Pinned by cordwood against the split boiler plate and slowly scalded to death, engineer William Ingram lived long enough to speak with would-be rescuers. Frank Evans, one of the guards, remembered: “With his last breath he warned away all who went near to try and aid him, declaring that there was danger of the boiler exploding and killing them.”

Evans describes the scene. “I hurried forward. On a curve in a deep cut we had met a heavily-laden coal train, traveling nearly as fast as we were. The trains had come together with that deadly crash. The two locomotives were raised high in air, face to face against each other, like giants grappling. The tender of our locomotive stood erect on one end. The engineer and fireman, poor fellows, were buried beneath the wood it carried. Perched on the reared-up end of the tender, high above the wreck, was one of our guards, sitting with his gun clutched in his hands, dead!. The front car of our train was jammed into a space of less than six feet. The two cars behind it were almost as badly wrecked. Several cars in the rear of those were also heaped together…Taken all in all, that wreck was a scene of horror such as few, even in the thick of battle, are ever doomed to be a witness of.”

Estimates of Confederate dead are surprisingly inexact. Most sources indicate 51 killed on the spot or dying within the first 24 hours. Other sources put their number as high as 60 to 72. 17 Union guards were killed on the spot, or died within a day of the wreck. 5 prisoners appear to have escaped in the confusion.

Captured at Spotsylvania early in 1864, 52nd North Carolina Infantry soldier James Tyner was in the Elmira camp at this time. Tyner’s brother William was one of the prisoners on board #171. William was badly injured in the wreck, surviving only long enough to avoid the 76′ trench in which the Confederate dead were buried. He died in Elmira three days later, never regaining consciousness.

I’ve always wondered if the brothers saw each other that one last time. James Tyner was my twice-great Grandfather, one of four brothers who had gone to war in 1861.

We’ll never know. James Tyner died in captivity on March 13, 1865, 27 days before Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. Of the four brothers, Nicholas alone survived the war, laying down his arms when the man they called “Marse Robert” surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant.

Afterward

Two Confederate soldiers, the brothers John and Michael Johnson, died overnight and were buried in the Congregational church yard across the Delaware river, in Barryville, New York. The remaining POWs killed immediately or shortly thereafter were buried in a common grave that night, alongside the track. Individual graves were dug for the 17 Union dead, and they too were laid alongside the track.

As the years went by, signs of all those graves were erased. Hundreds of trains carried thousands of passengers up and down the Erie Railroad, ignorant of the burial ground through which they passed.

The “pumpkin flood” of 1903 scoured the rail line uncovering many of the dead, carrying away at least some of their mortal remains, along with thousands of that year’s pumpkin crop.

On June 11, 1911, the forgotten dead of Shohola we’re disinterred, and reburied in mass graves in the Woodlawn National Cemetery, in Elmira, New York.

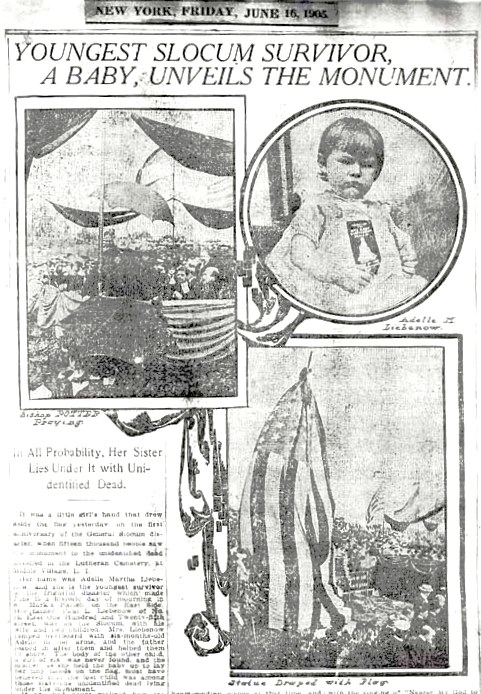

It was 9:30 on a beautiful late spring morning when the sidewheel passenger steamboat General Slocum, left the dock and steamed into New York’s East River.

It was 9:30 on a beautiful late spring morning when the sidewheel passenger steamboat General Slocum, left the dock and steamed into New York’s East River.

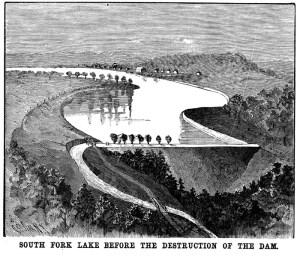

Traveling at 40 miles per hour, the 60′ wall of water and debris hit Johnstown 57 minutes after the dam broke. Some residents had managed to scramble to high ground, but most were caught by surprise by the flood waters.

Traveling at 40 miles per hour, the 60′ wall of water and debris hit Johnstown 57 minutes after the dam broke. Some residents had managed to scramble to high ground, but most were caught by surprise by the flood waters. When it was over, 2,209 were dead. 99 entire families had ceased to exist, including 396 children. 124 women and 198 men were widowed, 98 children orphaned. 777 people, over 1/3rd of the dead, were never identified. Their remains are buried in the “Plot of the Unknown” in Grandview Cemetery in Westmont.

When it was over, 2,209 were dead. 99 entire families had ceased to exist, including 396 children. 124 women and 198 men were widowed, 98 children orphaned. 777 people, over 1/3rd of the dead, were never identified. Their remains are buried in the “Plot of the Unknown” in Grandview Cemetery in Westmont.

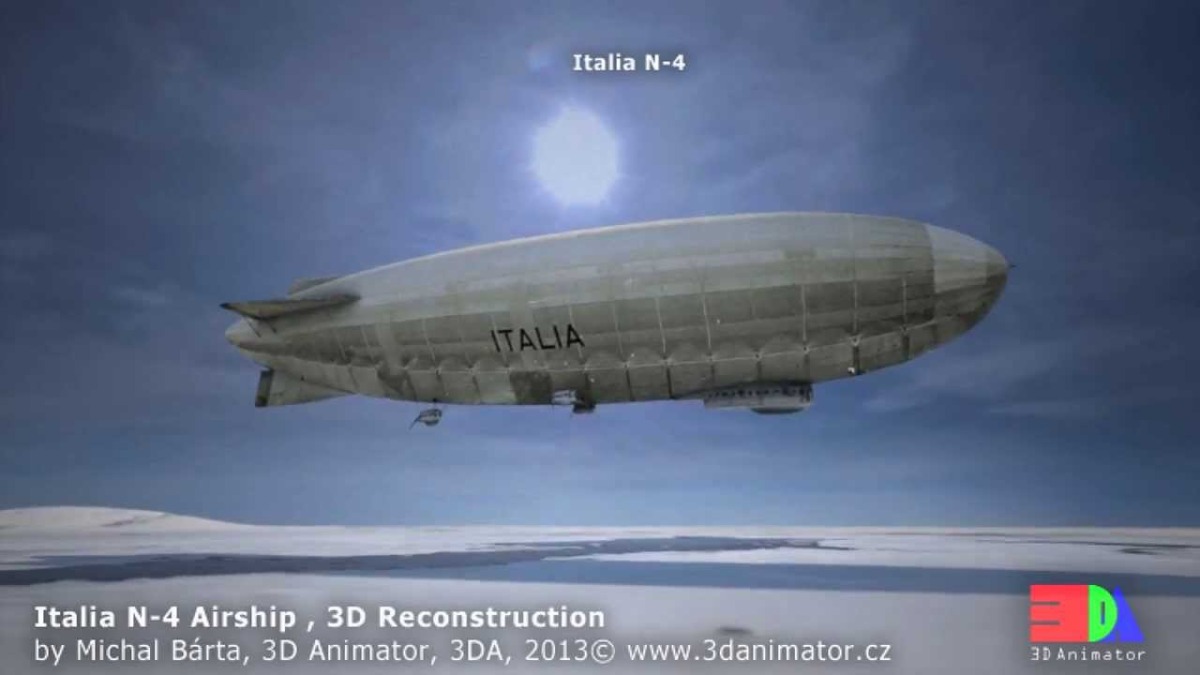

The first of five planned sorties began on May 11, before turning back only eight hours later in near blizzard conditions. The second trip took place in near perfect weather conditions and unlimited visibility, the craft covering 4,000 km (2,500 miles) and setting the stage for the third and final trip departing on May 23.

The first of five planned sorties began on May 11, before turning back only eight hours later in near blizzard conditions. The second trip took place in near perfect weather conditions and unlimited visibility, the craft covering 4,000 km (2,500 miles) and setting the stage for the third and final trip departing on May 23. envelope floated away, Chief Engineer Ettore Arduino started to throw everything he could get his hands on down to the men on the ice. These were the supplies intended for the descent to the pole, but they were now the only thing that stood between life and death. Arduino himself and the rest of the crew drifted away with the now helpless airship.

envelope floated away, Chief Engineer Ettore Arduino started to throw everything he could get his hands on down to the men on the ice. These were the supplies intended for the descent to the pole, but they were now the only thing that stood between life and death. Arduino himself and the rest of the crew drifted away with the now helpless airship.

grounded through the landing line, the ship’s fabric covering became charged in the electrically charged atmosphere, sending a spark to the air frame and igniting a hydrogen leak. Seven million cubic feet of hydrogen ignited almost simultaneously. It was over in less than 40 seconds.

grounded through the landing line, the ship’s fabric covering became charged in the electrically charged atmosphere, sending a spark to the air frame and igniting a hydrogen leak. Seven million cubic feet of hydrogen ignited almost simultaneously. It was over in less than 40 seconds. Where a person was inside the airship, had a lot to do with their chances of survival. Mr and Mrs Hermann Doehner and their three children (Irene, 16, Walter, 10, and Werner, 8) were in the dining room, watching the landing. Mr. Doehner left before the fire broke out. Mrs. Doehner and the two boys were able to jump out, but Irene went looking for her father. Both died in the crash.

Where a person was inside the airship, had a lot to do with their chances of survival. Mr and Mrs Hermann Doehner and their three children (Irene, 16, Walter, 10, and Werner, 8) were in the dining room, watching the landing. Mr. Doehner left before the fire broke out. Mrs. Doehner and the two boys were able to jump out, but Irene went looking for her father. Both died in the crash.

At the turn of the century there were over 450 textile factories in Manhattan alone, employing something like 40,000 garment workers. Many of them were young, immigrant women of Jewish and Italian ethnicity, working nine hours a day on weekdays and seven on Saturdays. Wages were typically low: $7 to $12 per week, equivalent to $3.20 to $5.50 per hour, in 2016.

At the turn of the century there were over 450 textile factories in Manhattan alone, employing something like 40,000 garment workers. Many of them were young, immigrant women of Jewish and Italian ethnicity, working nine hours a day on weekdays and seven on Saturdays. Wages were typically low: $7 to $12 per week, equivalent to $3.20 to $5.50 per hour, in 2016.

The plan was to attack the north tower of the World Trade Center in Manhattan, toppling it into the south tower and taking them both down.

The plan was to attack the north tower of the World Trade Center in Manhattan, toppling it into the south tower and taking them both down.

The terrorist device exploded at 12:17:37, hurling super-heated gasses from the blast center at thirteen times the speed of sound. Estimated pressure reached 150,000 psi, equivalent to the weight of 10 bull elephants.

The terrorist device exploded at 12:17:37, hurling super-heated gasses from the blast center at thirteen times the speed of sound. Estimated pressure reached 150,000 psi, equivalent to the weight of 10 bull elephants.

Roger Bannister became the first human to run a sub-four minute mile on May 6, 1954, with an official time of 3 minutes 59.4 seconds. The Jamaican sprinter Usain Bolt is recorded as the fastest man who ever lived. At the 2009 World Track and Field Championships, Bolt ran 100 meters at an average 23.35 mph from a standing start, and the 20 meters between the 60 & 80 markers at an average 27.79 mph.

Roger Bannister became the first human to run a sub-four minute mile on May 6, 1954, with an official time of 3 minutes 59.4 seconds. The Jamaican sprinter Usain Bolt is recorded as the fastest man who ever lived. At the 2009 World Track and Field Championships, Bolt ran 100 meters at an average 23.35 mph from a standing start, and the 20 meters between the 60 & 80 markers at an average 27.79 mph. smashing the elevated train tracks on Atlantic Ave and hurling entire buildings from their foundations. Horses, wagons, and dogs were caught up with broken buildings and scores of people as the brown flood sped across the North End. Twenty municipal workers were eating lunch in a nearby city building when they were swept away, parts of the building thrown fifty yards. Part of the tank wall fell on a nearby fire house, crushing the building and burying three firemen alive.

smashing the elevated train tracks on Atlantic Ave and hurling entire buildings from their foundations. Horses, wagons, and dogs were caught up with broken buildings and scores of people as the brown flood sped across the North End. Twenty municipal workers were eating lunch in a nearby city building when they were swept away, parts of the building thrown fifty yards. Part of the tank wall fell on a nearby fire house, crushing the building and burying three firemen alive. In 1983, a Smithsonian Magazine article described the experience of one child: “Anthony di Stasio, walking homeward with his sisters from the Michelangelo School, was picked up by the wave and carried, tumbling on its crest, almost as though he were surfing. Then he grounded and the molasses rolled him like a pebble as the wave diminished. He heard his mother call his name and couldn’t answer, his throat was so clogged with the smothering goo. He passed out, then opened his eyes to find three of his four sisters staring at him”.

In 1983, a Smithsonian Magazine article described the experience of one child: “Anthony di Stasio, walking homeward with his sisters from the Michelangelo School, was picked up by the wave and carried, tumbling on its crest, almost as though he were surfing. Then he grounded and the molasses rolled him like a pebble as the wave diminished. He heard his mother call his name and couldn’t answer, his throat was so clogged with the smothering goo. He passed out, then opened his eyes to find three of his four sisters staring at him”.

You must be logged in to post a comment.