In April 1865, the Civil War was all but ended. General Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant on the 9th. President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated five days later, and John Wilkes Booth run to ground and killed on the 26th. Thousands of former POWs were being released from Confederate camps in Alabama and Georgia, and held in regional parole camps.

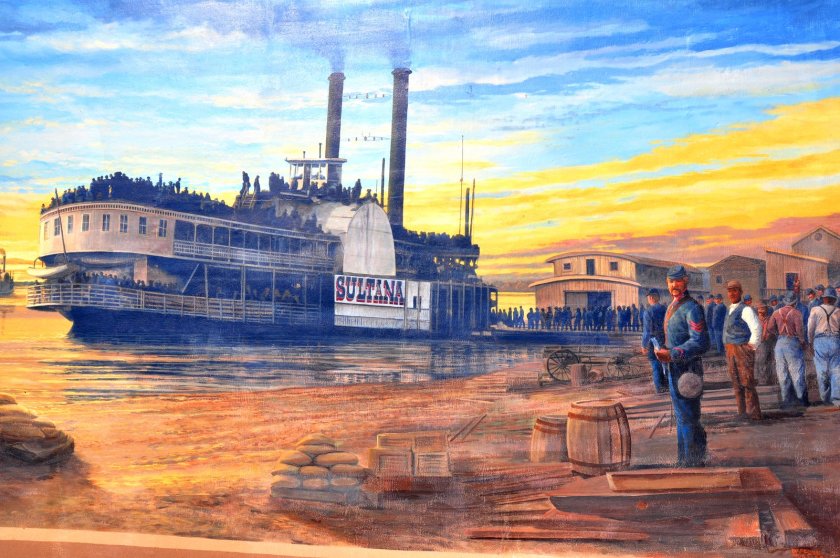

The sidewheel steamboat Sultana left New Orleans with about 100 passengers and a few head of livestock, pulling into Vicksburg Mississippi on the 21st to repair a damaged boiler and to pick up a promised load of passengers.

The mechanic wanted to cut a bulging seam out of the boiler and install a new plate, easily three day’s work. Captain J. Cass Mason declined, for fear of losing his passengers. He wanted the seam hammered back into place and covered with a patch, and he wanted it done in a day.

The passengers Mason was so afraid of losing were former prisoners of the Confederacy, and Confederate parolees, returning to their homes in Kentucky and Tennessee.

The Federal government was paying $5 each to anyone bringing enlisted guys home, and $10 apiece for officers. Lieutenant Colonel Reuben Hatch, chief quartermaster at Vicksburg and one of the sleazier characters in this story, had approached Captain Mason with a deal. Hatch would guarantee a minimum of 1,400 passengers, and they’d both walk away with a pocketful of cash.

As it was, there were other riverboats in the vicinity. Mason didn’t have time to worry about boiler repairs.

The decks creaked and sagged, as beams were installed to shore up the load. Sultana backed away from the dock on April 24, with 2,427 passengers. More than six times her legal limit of 376.

Sultana spent two days traveling upstream, fighting one of the heaviest spring floods in the history of the Mississippi River. She arrived at Memphis on the evening of the 26th, unloading 120 tons of sugar from her holds. Already massively top heavy, the riverboat now lurched from side to side with every turn.

The crew must have exceeded allowable steam pressure, pushing all that load against the current. Pressure varied wildly inside Sultana’s four giant boilers, as water sloshed from one to the next with every turn, boiling water flashing to superheated steam and back to water.

The temporary boiler patch exploded at 2:00am on April 27, detonating two more boilers a split second later. The force of the explosion hurled hundreds into the icy black water. The top decks soon gave way, as hundreds tumbled into the gaping maw of the fire boxes below.

Within moments, the entire riverboat was ablaze. Those who weren’t incinerated outright now had to take their chances in the swift moving waters of the river. Already weakened by terms in captivity, they died by the hundreds of drowning or hypothermia.

The drifting and burnt out hulk of the Sultana sank to the bottom, seven hours later. The steamers Silver Spray, Jenny Lind, and Pocohontas joined the rescue effort, along with the navy tinclad Essex and the sidewheel gunboat USS Tyler. 700 were plucked from the water and taken to Memphis hospitals, of whom 200 later died of burns or exposure. Bodies would continue to wash ashore, for months.

Sultana was the worst maritime disaster in United States history, though its memory was mostly swept away in the tide of events that April. The United States Customs Service records an official count of 1,800 killed, though the true number will never be known. Titanic went down in the North Atlantic 47 years later, taking 1,512 with her.

Despite the enormity of the disaster, no one was ever held accountable. One Union officer, Captain Frederick Speed, was found guilty of grossly overcrowding the riverboat. It was he who sent 2,100 prisoners from their parole camp into Vicksburg, but his conviction was later overturned. It seems that higher ranking officials may have tried to make him into a scapegoat, since he never so much as laid eyes on Sultana herself.

Captain Williams, the officer who actually put all those people onboard, was a West Point graduate and regular army officer. The army didn’t seem to want to go after one of its own. Captain Mason and all of his officers were killed in the disaster. Reuben Hatch, the guy who concocted the whole scheme in the first place, resigned shortly after the disaster, thereby putting himself outside the reach of a military tribunal.

The last survivor of the Sultana disaster, Private Charles M. Eldridge of the 3rd (Confederate) Tennessee Cavalry, died at his home at the age of 96 on September 8, 1941. Three months before the Imperial Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

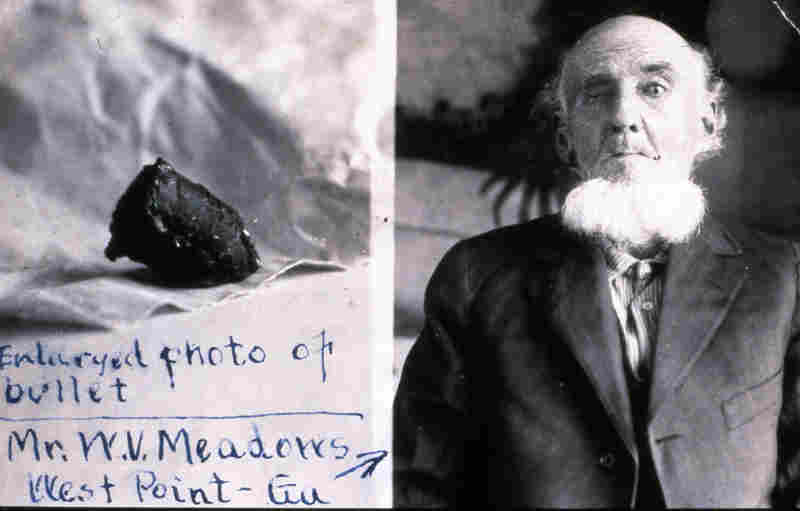

Fifty-nine years earlier, nineteen-year-old Willis V. Meadows signed up with his brothers and his cousins, enlisting in Company G of the 37th Alabama Volunteer Infantry.

Fifty-nine years earlier, nineteen-year-old Willis V. Meadows signed up with his brothers and his cousins, enlisting in Company G of the 37th Alabama Volunteer Infantry. Willis fell over apparently dead, blood streaming out of his eye with the bullet lodged near his brain. The battle moved on. Vicksburg Mississippi fell to the Union army on July 4, 1863. The “Confederate Gibraltar” wouldn’t celebrate another Independence Day, for 80 years.

Willis fell over apparently dead, blood streaming out of his eye with the bullet lodged near his brain. The battle moved on. Vicksburg Mississippi fell to the Union army on July 4, 1863. The “Confederate Gibraltar” wouldn’t celebrate another Independence Day, for 80 years. Willis Meadows and Peter Knapp might have walked off the page of their time and on to obscurity, but for a circumstance even more unlikely, than a man holding a bullet in his head for fifty-eight years.

Willis Meadows and Peter Knapp might have walked off the page of their time and on to obscurity, but for a circumstance even more unlikely, than a man holding a bullet in his head for fifty-eight years. It’s remarkable enough that Peter Knapp survived the brutality of the notorious Andersonville prison camp, an institution described as the “Auschwitz of the Civil War”. The Union POW camp at Elmira New York might be described as the Andersonville of the North. My own thrice-Great Grandfather went to his final rest there, along with his brother.

It’s remarkable enough that Peter Knapp survived the brutality of the notorious Andersonville prison camp, an institution described as the “Auschwitz of the Civil War”. The Union POW camp at Elmira New York might be described as the Andersonville of the North. My own thrice-Great Grandfather went to his final rest there, along with his brother. In 2012, Alice Knapp was researching the genealogical records of her deceased husband Steve, when she came upon the story of his ancestor. Stunned to learn that he had never been buried, Ms. Knapp called the Portland crematorium. ‘Yeah, he’s here’. Alice Knapp got the death certificate in Washington. I “called back and said, ‘By the way, is his wife there?’ and they said, ‘Yeah.’ The shock was that he was not ever buried. That was the surprise to me.”

In 2012, Alice Knapp was researching the genealogical records of her deceased husband Steve, when she came upon the story of his ancestor. Stunned to learn that he had never been buried, Ms. Knapp called the Portland crematorium. ‘Yeah, he’s here’. Alice Knapp got the death certificate in Washington. I “called back and said, ‘By the way, is his wife there?’ and they said, ‘Yeah.’ The shock was that he was not ever buried. That was the surprise to me.”

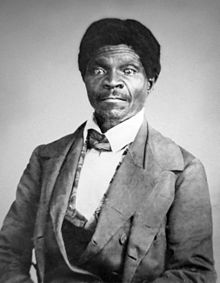

Dr. Emerson died in 1842, leaving his estate to his wife Eliza, who continued to lease the Scotts out as hired slaves.

Dr. Emerson died in 1842, leaving his estate to his wife Eliza, who continued to lease the Scotts out as hired slaves.

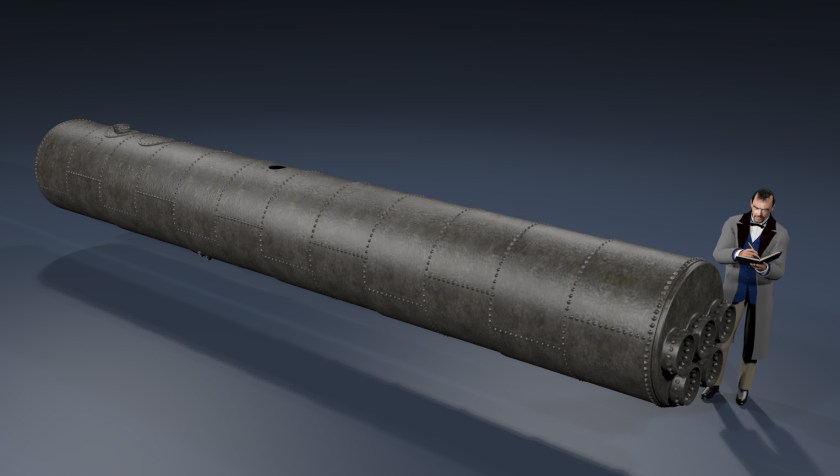

A second crew tested the submarine on October 15, this one including Horace Hunley himself. The submarine conducted a mock attack but failed to surface afterward, this time drowning all 8 crew members.

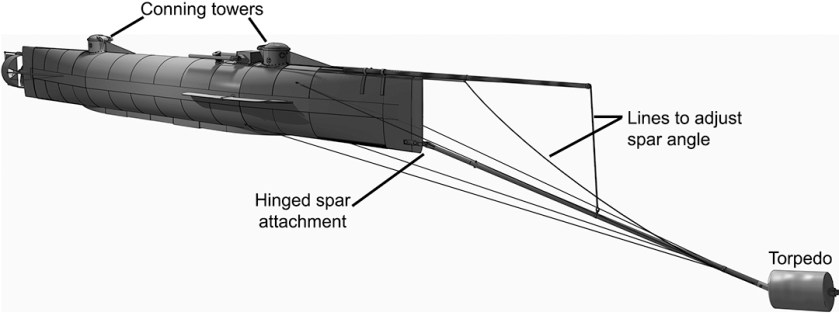

A second crew tested the submarine on October 15, this one including Horace Hunley himself. The submarine conducted a mock attack but failed to surface afterward, this time drowning all 8 crew members. Tide and current conditions in Charleston proved very different from those in Mobile. On several test runs, the torpedo floated out ahead of the sub. That wouldn’t do, so a spar was fashioned and mounted to the bow. At the end of the spar was a 137lb waterproof cask of powder, attached to a harpoon-like device with which Hunley would ram its target.

Tide and current conditions in Charleston proved very different from those in Mobile. On several test runs, the torpedo floated out ahead of the sub. That wouldn’t do, so a spar was fashioned and mounted to the bow. At the end of the spar was a 137lb waterproof cask of powder, attached to a harpoon-like device with which Hunley would ram its target.

On the coin, clearly showing signs of having been struck by a bullet, are inscribed these words:

On the coin, clearly showing signs of having been struck by a bullet, are inscribed these words:

On that July morning, no one had any idea of the years-long bloodbath that lay ahead. 35,000 Federal troops, 90-day recruits all, had arrived to crush a trifling force of rebels. Then on to Richmond, the Confederate capitol, and the end of the uprising.

On that July morning, no one had any idea of the years-long bloodbath that lay ahead. 35,000 Federal troops, 90-day recruits all, had arrived to crush a trifling force of rebels. Then on to Richmond, the Confederate capitol, and the end of the uprising.

Jackson believed that slavery existed because the Creator willed it. His mission was to save their souls, by teaching them the Old Testament, the Ten Commandments, the Lord’s Prayer and the Apostle’s Creed.

Jackson believed that slavery existed because the Creator willed it. His mission was to save their souls, by teaching them the Old Testament, the Ten Commandments, the Lord’s Prayer and the Apostle’s Creed.

On July 28, 1866, the Army Reorganization Act authorized the formation of 30 new units, including two cavalry and four infantry regiments “which shall be composed of colored men.”

On July 28, 1866, the Army Reorganization Act authorized the formation of 30 new units, including two cavalry and four infantry regiments “which shall be composed of colored men.” The original units fought in the American Indian Wars, the Spanish-American War, the Philippine-American War, the Border War and two World Wars, amassing 22 Medals of Honor by the end of WW1.

The original units fought in the American Indian Wars, the Spanish-American War, the Philippine-American War, the Border War and two World Wars, amassing 22 Medals of Honor by the end of WW1.

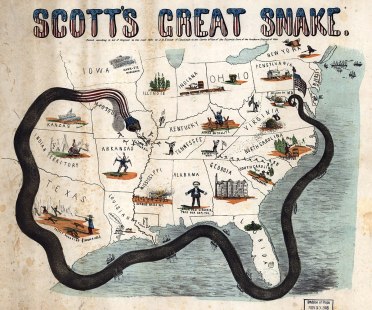

President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation soon after taking office, threatening to blockade southern coastlines. It wasn’t long before the “Anaconda Plan” went into effect, a naval blockade extending 3,500 miles along the Atlantic coastline and Gulf of Mexico, up into the lower Mississippi River.

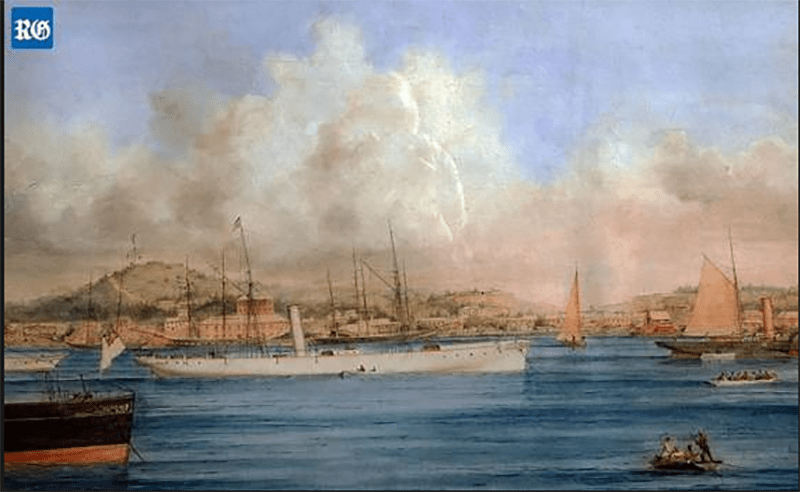

President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation soon after taking office, threatening to blockade southern coastlines. It wasn’t long before the “Anaconda Plan” went into effect, a naval blockade extending 3,500 miles along the Atlantic coastline and Gulf of Mexico, up into the lower Mississippi River. Cotton would ship out of Mobile, Charleston, Wilmington and other ports, while weapons and other manufactured goods would come back in. Sometimes, these goods would make the whole trans-Atlantic voyage. Often, they would stop at neutral ports in Cuba or the Bahamas.

Cotton would ship out of Mobile, Charleston, Wilmington and other ports, while weapons and other manufactured goods would come back in. Sometimes, these goods would make the whole trans-Atlantic voyage. Often, they would stop at neutral ports in Cuba or the Bahamas.

You must be logged in to post a comment.