It was the Golden Age of Greek history, a time when “[Men] lived like gods without sorrow of heart, remote and free from toil and grief…”, according to the Greek poet Hesiod. A time of Confucius and the Buddha in the east while the Olmec peoples ruled over much of South and Central America, a time when the Italian city-state of Rome overthrew a Monarch, to form a Republic.

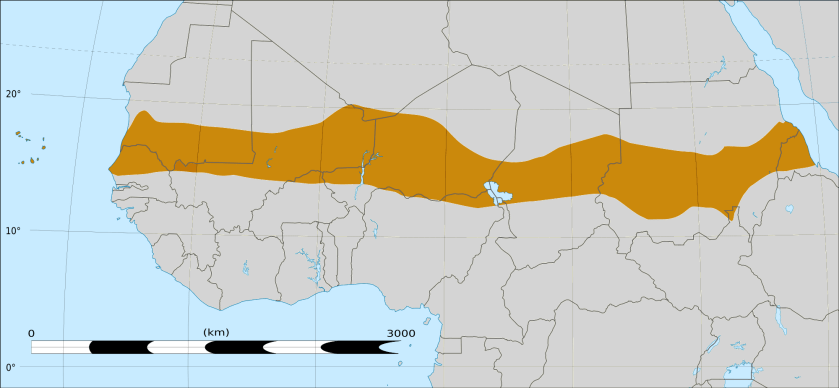

2,500 years ago, Bantu farmers on the African continent began to spread out across the land as the first Africans penetrated the dense rain forests of the equator, to take up a new life on the west African coast.

2,500 years ago, Bantu farmers on the African continent began to spread out across the land as the first Africans penetrated the dense rain forests of the equator, to take up a new life on the west African coast.

The Islamic crusades of the 7th and 8th centuries turned much of the Maghreb (northwest Africa) to Islam and displaced the Sahelian kingdoms of the sub-Saharan grasslands. The hunters, farmers and traders of Coastal Africa remained free to make their own way, isolated by those same rain forests from the jihads and other violence of the interior.

The first European contact came around 1462 when the Portuguese explorer Pedro de Sintra mapped the hills surrounding modern Freetown Harbour, naming an oddly shaped formation Serra Lyoa (Lioness Mountain).

Home to one of the few safe harbors on the surf-battered “windward coast”, Sierra Leone soon became a favorite of European mariners, some of whom remained for a time while others came to stay, intermarrying with local women.

Home to one of the few safe harbors on the surf-battered “windward coast”, Sierra Leone soon became a favorite of European mariners, some of whom remained for a time while others came to stay, intermarrying with local women.

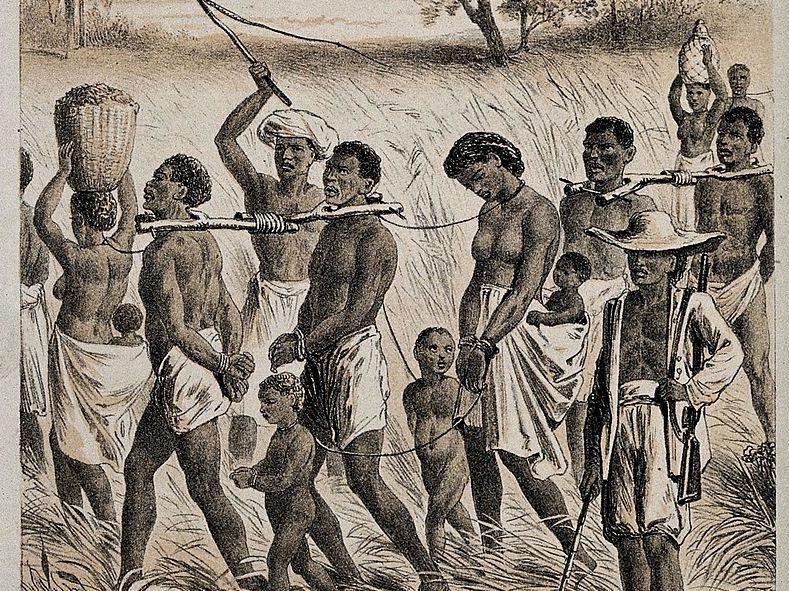

From the 6th century to a peak of around 1350, Arab slave traders conducted a rich trans-Saharan trade in human beings.

According to the Guyanese historian Walter Rodney, slavery among and between the African peoples of Sierra Leone appears to be rare at this time. Portuguese mariners kept detailed records and would have described such a thing though there was a particular kind of “slavery” in the region: “A person in trouble in one kingdom could go to another and place himself under the protection of its king, whereupon he became a “slave” of that king, obliged to provide free labour and liable for sale“. While this type of “slave” retained rudimentary rights at this time, those unfortunate enough to be captured by Dutch, English and French slavers, did not.

While this type of “slave” retained rudimentary rights at this time, those unfortunate enough to be captured by Dutch, English and French slavers, did not.

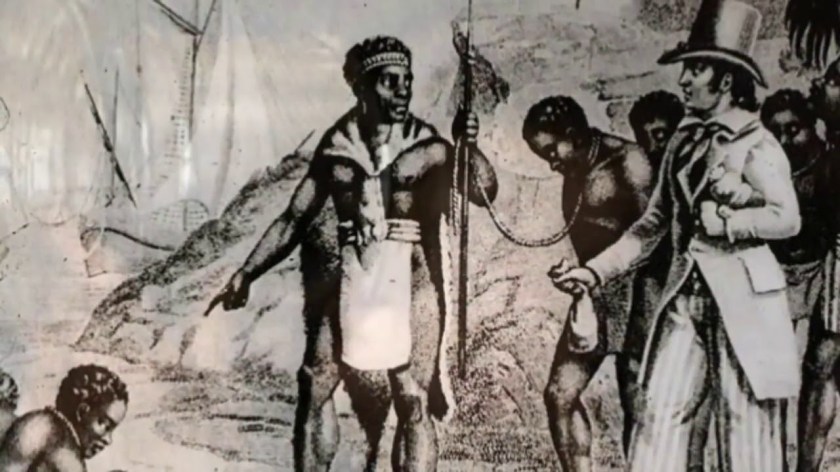

It wasn’t long before coastal kidnapping raids gave way to more lucrative opportunities. Some chiefs were more than happy to “sell” the less desirable members of their own tribes while others made a business out of war, taking prisoners to be traded for a fortune in European goods, including muskets.

While slave “owners” were near-exclusively white and foreign at this time, the late 18th century was a time of rich and powerful African chieftains, many of whom owned large numbers of slaves, of their own. This was the world of John Newton, born July 24 (old style) 1725 and destined to a life, in the slave trade.

This was the world of John Newton, born July 24 (old style) 1725 and destined to a life, in the slave trade.

The son of a London shipmaster in the Mediterranean service, Newton first went to sea with his father at age 11 and logged six such voyages before the elder Newton retired, in 1742.

His was a wild youth, the life of a sailor bent on drinking and carousing and raising hell. That was all brought up short in 1743, when Newton was captured and “pressed” into service with the 50-gun HMS Harwich, given the rank of midshipman.

The teenager hated everything about it and tried to desert, earning himself a flogging for his troubles. Eight. Dozen. Lashes. Imagine enduring something like that.

Reduced to the rank of common seaman Newton was disgraced, wounded and humiliated. He plotted to murder the captain and hurl himself overboard but it wasn’t meant to be. His wounds healed over in time and, with the Harwich en route to India, Newton transferred to the slave ship Pegasus, bound for West Africa.

Pegasus would trade goods for slaves in Sierra Leone to be shipped to colonies in the Caribbean and North America. Newton hated life on the Pegasus as much as they, hated him. In 1745, they left him in West Africa with slave trader Amos Clowe. Newton was now himself a slave, given by Clowe to his wife Princess Peye of the Sherbro tribe. Peye treated Newton as horribly as any of her other slaves. Newton himself later described these three years as “once an infidel and a libertine, [now] a servant of slaves in West Africa”.

Newton hated life on the Pegasus as much as they, hated him. In 1745, they left him in West Africa with slave trader Amos Clowe. Newton was now himself a slave, given by Clowe to his wife Princess Peye of the Sherbro tribe. Peye treated Newton as horribly as any of her other slaves. Newton himself later described these three years as “once an infidel and a libertine, [now] a servant of slaves in West Africa”.

Rescued in 1748 at the request of his father, Newton was returning to England aboard the merchant ship Greyhound, when he experienced a spiritual awakening. Caught in a dreadful storm off Donegal, Greyhound seemed doomed when a great hole opened in her hull. He prayed for the mercy of God when a load somehow shifted, partially blocking the hole. In time, the storm died down. Greyhound made port in Lough Swilly, Ireland, four weeks later.

With this conversion, John Newton had come to accept the doctrines of Evangelical Christianity. On March 10, 1748 he swore off liquor, gambling and profanity. He would remember this day as a turning point, for the rest of his life.

There’s a popular story that Newton’s life was changed then and there but it didn’t work out that way. Those hours of despair on board the Greyhound were an awakening, yes, but Newton would return to the slave trade. Even after the 1754 stroke which ended his seafaring career, he still invested in slaving operations.

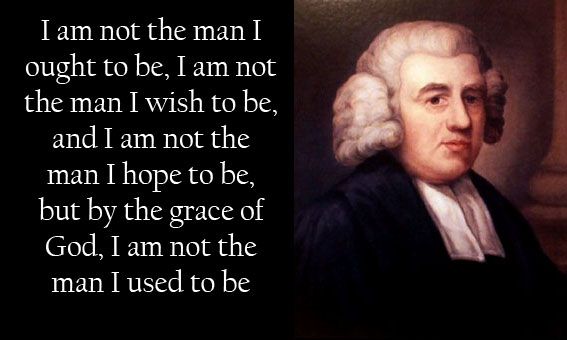

His was a gradual conversion. “I cannot consider myself to have been a believer in the full sense of the word” he later said, “until a considerable time afterwards.”

While working as tax collector in the Port of Liverpool, Newton studied Greek, Hebrew, and Syriac, preparing himself for serious religious studies. He applied to become an ordained minister of the Anglican Church in 1757. Seven years would come and go when the lay minister applied with Methodists, Independents and Presbyterians. He was ordained a priest of the Anglican church on April 29, 1764.

Moving to London in 1780 as the Rector of St. Mary Woolnoth church, Newton became involved with the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

Moving to London in 1780 as the Rector of St. Mary Woolnoth church, Newton became involved with the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

In 1788, Newton broke a long silence on the subject to take a forceful stand, against the “peculiar institution“. In his Thoughts Upon the African Slave Trade, Newton writes:

“So much light has been thrown upon the subject…for the suppression of a traffic, which contradicts the feelings of humanity; that it is hoped, this stain of our National character will soon be wiped out.”

Newton apologized for his past in “a confession, which … comes too late … It will always be a subject of humiliating reflection to me, that I was once an active instrument in a business at which my heart now shudders.”

The tract went on to two printings, describing the hideous conditions on board the slave ships and leading to the abolition of the slave trade, in 1807. William Cowper was an English poet and hymnist who came to worship in Newton’s church, in 1767. The pair collaborated on a book of Newton’s hymns including “Glorious Things of Thee Are Spoken,” “How Sweet the Name of Jesus Sounds!,” “Come, My Soul, Thy Suit Prepare” and others.

William Cowper was an English poet and hymnist who came to worship in Newton’s church, in 1767. The pair collaborated on a book of Newton’s hymns including “Glorious Things of Thee Are Spoken,” “How Sweet the Name of Jesus Sounds!,” “Come, My Soul, Thy Suit Prepare” and others.

“I am still in the land of the dying; I shall be in the land of the living soon”. His last words

Today, the carousing sailor and slave trader-turned English clergyman John Newton is remembered the world over for his 1772 work, the most famous hymn in history… “Amazing Grace“.

Amazing grace, how sweet the sound,

that saved a wretch like me.

I once was lost, but now am found,

Was blind but now I see.

The fifty gun HMS Romney arrived in May, 1769. Customs officials seized John Hancock’s merchant sloop “Liberty” the following month, on allegations the vessel was involved in smuggling. Already agitated over Romney’s impressment of local sailors, Bostonians began to riot. By October, the first of four regular British army regiments arrived in Boston.

The fifty gun HMS Romney arrived in May, 1769. Customs officials seized John Hancock’s merchant sloop “Liberty” the following month, on allegations the vessel was involved in smuggling. Already agitated over Romney’s impressment of local sailors, Bostonians began to riot. By October, the first of four regular British army regiments arrived in Boston. Edward Garrick was a wigmaker’s apprentice, who worked each day to grease and powder and curl the long hair of the soldier’s wigs.

Edward Garrick was a wigmaker’s apprentice, who worked each day to grease and powder and curl the long hair of the soldier’s wigs. The two sides stopped for a few seconds to two minutes, depending on the witness. Then they all fired. A ragged, ill-disciplined volley. There was no order, just the flash and roar of gunpowder on the cold late afternoon streets of a Winter’s day. It was March 5. When the smoke cleared, three were dead. Two more lay mortally wounded and another six, seriously injured.

The two sides stopped for a few seconds to two minutes, depending on the witness. Then they all fired. A ragged, ill-disciplined volley. There was no order, just the flash and roar of gunpowder on the cold late afternoon streets of a Winter’s day. It was March 5. When the smoke cleared, three were dead. Two more lay mortally wounded and another six, seriously injured.

The Father/Son team tee’d off in match against the brothers Willie and Mungo Park on September 11, 1875. With two holes to go, Young Tom received a telegram with upsetting news. His wife Margaret had gone into a difficult labor. The Morrises finished those last two holes winning the match, and hurried home by ship across the Firth of Forth and up the coast. Too late. Tom Morris Jr. got home to find that his young wife and newborn baby, had both died in childbirth.

The Father/Son team tee’d off in match against the brothers Willie and Mungo Park on September 11, 1875. With two holes to go, Young Tom received a telegram with upsetting news. His wife Margaret had gone into a difficult labor. The Morrises finished those last two holes winning the match, and hurried home by ship across the Firth of Forth and up the coast. Too late. Tom Morris Jr. got home to find that his young wife and newborn baby, had both died in childbirth.

When Nazi Germany invaded Poland the following September, London Mayor Herbert Morrison was at 10 Downing Street, meeting with Chamberlain’s aide, Sir Horace Wilson. Morrison believed that the time had come for Operation Pied Piper. Only a year to the day from the Prime Minister’s “Peace in our Time” declaration, Wilson protested. “But we’re not at war yet, and we wouldn’t want to do anything to upset delicate negotiations, would we?”

When Nazi Germany invaded Poland the following September, London Mayor Herbert Morrison was at 10 Downing Street, meeting with Chamberlain’s aide, Sir Horace Wilson. Morrison believed that the time had come for Operation Pied Piper. Only a year to the day from the Prime Minister’s “Peace in our Time” declaration, Wilson protested. “But we’re not at war yet, and we wouldn’t want to do anything to upset delicate negotiations, would we?”

This was no mindless panic. Zeppelin raids had killed 1,500 civilians in London alone during the ‘Great War’. Since then, governments had become infinitely better at killing each other’s citizens.

This was no mindless panic. Zeppelin raids had killed 1,500 civilians in London alone during the ‘Great War’. Since then, governments had become infinitely better at killing each other’s citizens. All things considered, the evacuation of all that humanity ran relatively smoothly. James Roffey, founder of the Evacuees Reunion Association, recalls ‘We marched to Waterloo Station behind our head teacher carrying a banner with our school’s name on it. We all thought it was a holiday, but the only thing we couldn’t work out was why the women and girls were crying.’

All things considered, the evacuation of all that humanity ran relatively smoothly. James Roffey, founder of the Evacuees Reunion Association, recalls ‘We marched to Waterloo Station behind our head teacher carrying a banner with our school’s name on it. We all thought it was a holiday, but the only thing we couldn’t work out was why the women and girls were crying.’ In the 2003 BBC Radio documentary “Evacuation: The True Story,” clinical psychologist Steve Davis described the worst cases, as “little more than a pedophile’s charter.”

In the 2003 BBC Radio documentary “Evacuation: The True Story,” clinical psychologist Steve Davis described the worst cases, as “little more than a pedophile’s charter.” Authorities produced posters urging parents to leave the kids where they were and a good thing, too. The Blitz against London itself began on September 7. The city experienced the most devastating attack to-date on December 29, in a blanket fire-bombing that killed almost 3,600 civilians.

Authorities produced posters urging parents to leave the kids where they were and a good thing, too. The Blitz against London itself began on September 7. The city experienced the most devastating attack to-date on December 29, in a blanket fire-bombing that killed almost 3,600 civilians. “Operation Steinbock”, the Luftwaffe’s last large-scale strategic bombing campaign of the war against southern England, was carried out three years later. On this day in 1944, 285 German bombers attacked London in what the Brits called, a “Baby Blitz”.

“Operation Steinbock”, the Luftwaffe’s last large-scale strategic bombing campaign of the war against southern England, was carried out three years later. On this day in 1944, 285 German bombers attacked London in what the Brits called, a “Baby Blitz”. Late in the war, the subsonic “Doodle Bug” or V1 “flying bomb” was replaced by the terrifying supersonic

Late in the war, the subsonic “Doodle Bug” or V1 “flying bomb” was replaced by the terrifying supersonic  In the end, many family ‘reunions’ were as emotionally bruising as the original breakup. Years had come and gone and new relationships had formed. The war had turned biological family members, into all but strangers.

In the end, many family ‘reunions’ were as emotionally bruising as the original breakup. Years had come and gone and new relationships had formed. The war had turned biological family members, into all but strangers.

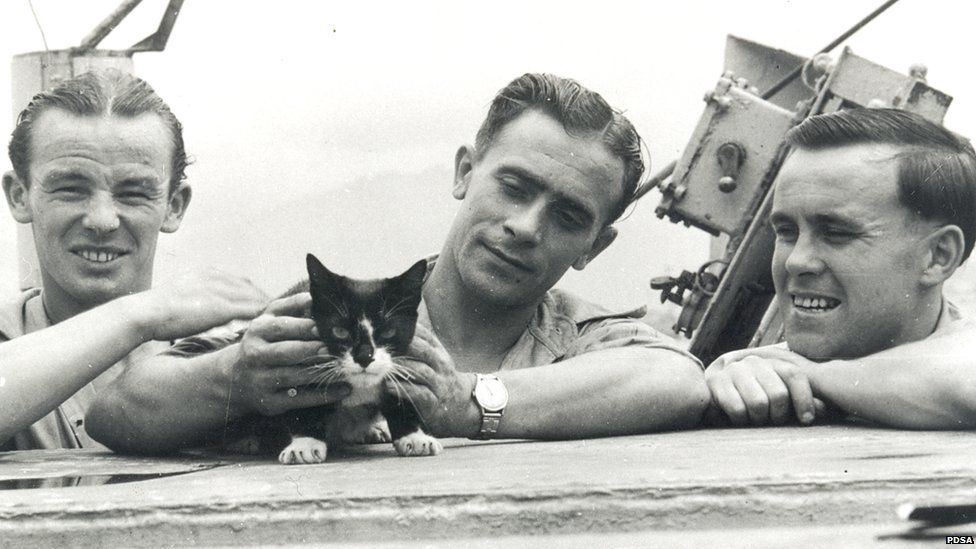

Simon earned the admiration of the Amethyst crew, with his prowess as a rat killer. Seamen learned to check their beds for “presents” of dead rats while Simon himself could usually be found, curled up and sleeping in the Captain’s hat.

Simon earned the admiration of the Amethyst crew, with his prowess as a rat killer. Seamen learned to check their beds for “presents” of dead rats while Simon himself could usually be found, curled up and sleeping in the Captain’s hat.

All but unseen amidst the economic devastation of World War 1, the domesticated animals of Great Britain were in desperate straits. Turn-of-the-century social reformer Maria Elizabeth “Mia” Dickin founded the People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals (PDSA) in 1917, working to lighten the dreadful state of animal health in Whitechapel, London. To this day, the PDSA is one of the largest veterinary charities in the United Kingdom, conducting over a million free veterinary consultations, every year.

All but unseen amidst the economic devastation of World War 1, the domesticated animals of Great Britain were in desperate straits. Turn-of-the-century social reformer Maria Elizabeth “Mia” Dickin founded the People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals (PDSA) in 1917, working to lighten the dreadful state of animal health in Whitechapel, London. To this day, the PDSA is one of the largest veterinary charities in the United Kingdom, conducting over a million free veterinary consultations, every year.

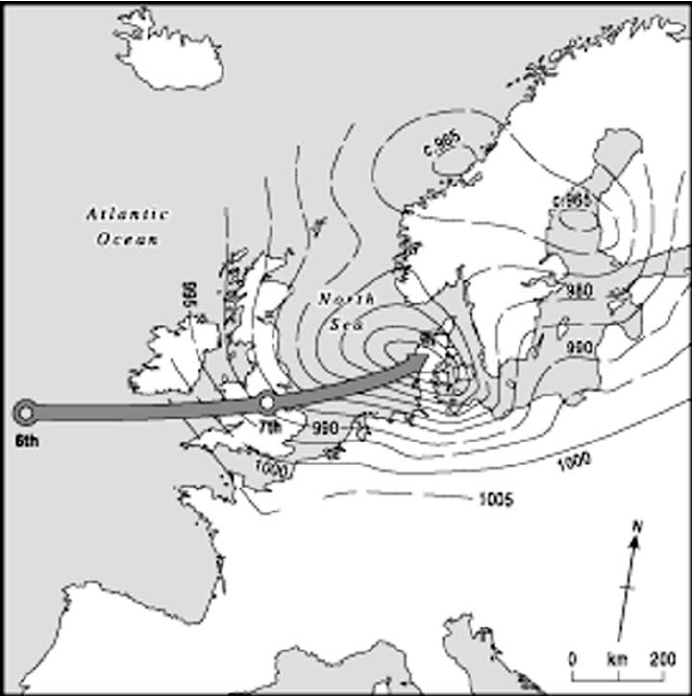

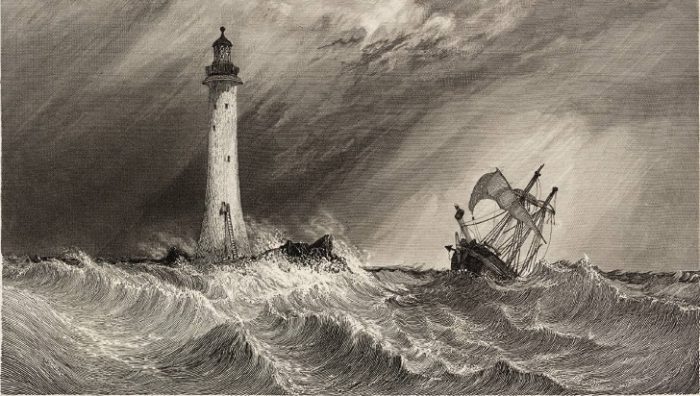

Beginning in early November, a series of gales drove hundreds of ships up the Thames estuary, is search of shelter. The “Perfect Hurricane” of 1703 arrived on November 24 (Old Style) and remained until December 2 with the worst of the storm on November 26-27.

Beginning in early November, a series of gales drove hundreds of ships up the Thames estuary, is search of shelter. The “Perfect Hurricane” of 1703 arrived on November 24 (Old Style) and remained until December 2 with the worst of the storm on November 26-27. The most miraculous tale of survival was that of Thomas Atkins, a sailor aboard the HMS Mary. As Mary broke apart, Atkins watched as Rear Admiral Beaumont climbed aboard a piece of her quarter deck, only to be washed away. Atkins himself was lifted high on a wave and deposited on the decks of another ship, the HMS Stirling Castle. He was soon in the water again as Stirling Castle broke up and sank, only to thrown by yet another wave, this time landing in a small boat. Atkins alone survived the maelstrom, of the 269 men aboard HMS Mary.

The most miraculous tale of survival was that of Thomas Atkins, a sailor aboard the HMS Mary. As Mary broke apart, Atkins watched as Rear Admiral Beaumont climbed aboard a piece of her quarter deck, only to be washed away. Atkins himself was lifted high on a wave and deposited on the decks of another ship, the HMS Stirling Castle. He was soon in the water again as Stirling Castle broke up and sank, only to thrown by yet another wave, this time landing in a small boat. Atkins alone survived the maelstrom, of the 269 men aboard HMS Mary.

Barack Obama wrote in his memoir “Dreams from my Father”, that his grandfather Hussein Onyango Obama was captured and tortured by British authorities during the Mau Mau uprising. The now-former President wrote that his father was “selected by Kenyan leaders and American sponsors to attend a university in the United States, joining the first large wave of Africans to be sent forth to master Western technology and bring it back to forge a new, modern Africa“.

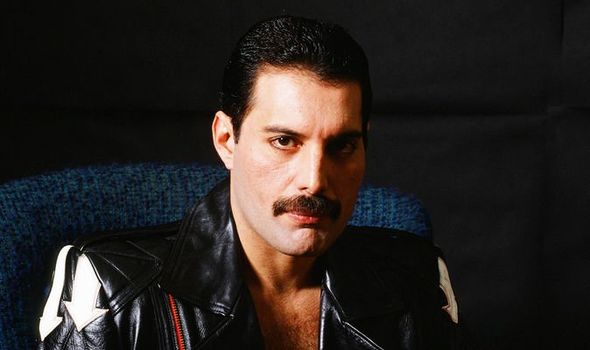

Barack Obama wrote in his memoir “Dreams from my Father”, that his grandfather Hussein Onyango Obama was captured and tortured by British authorities during the Mau Mau uprising. The now-former President wrote that his father was “selected by Kenyan leaders and American sponsors to attend a university in the United States, joining the first large wave of Africans to be sent forth to master Western technology and bring it back to forge a new, modern Africa“. If you’re interested in a little pop culture sauce to go with this turkey, the Mau Mau uprising inspired a number of similar rebellions throughout the region. One of them occurred in the East African coastal city of Zanzibar.

If you’re interested in a little pop culture sauce to go with this turkey, the Mau Mau uprising inspired a number of similar rebellions throughout the region. One of them occurred in the East African coastal city of Zanzibar.

You must be logged in to post a comment.