Hindenburg left Frankfurt airfield on its last flight at 7:16pm, May 3, 1937, carrying 97 passengers and crew. Crossing over Cologne, Beachy Head and Newfoundland, the airship arrived over Boston at noon on the 6th. By 3:00pm it was over the skyscrapers of Manhattan, arriving at the Naval Air Station in Lakehurst, NJ at 4:15.

Foul weather had caused a half-day’s delay, but the landing was eventually cleared. The final S turn approach executed at 7:21pm. The ship was at the mooring mast, 180′ from the ground with forward landing ropes deployed, when flames first erupted near the top tail fin.

Eyewitness accounts differ as to the origin of the fire. The leading theory is that, with the metal framework grounded through the landing line, the ship’s fabric covering became charged in the electrically charged atmosphere, sending a spark to the air frame and igniting a hydrogen leak. Seven million cubic feet of hydrogen ignited almost simultaneously. It was over in less than 40 seconds.

grounded through the landing line, the ship’s fabric covering became charged in the electrically charged atmosphere, sending a spark to the air frame and igniting a hydrogen leak. Seven million cubic feet of hydrogen ignited almost simultaneously. It was over in less than 40 seconds.

The largest dirigible ever built, an airship the size of Titanic, burst into flames as the hull collapsed and plummeted to the ground. Passengers and crew jumped for their lives and scrambled to safety, along with ground crews who had moments earlier been positioned to receive the ship.

The famous film shows ground crew running for their lives, and then turning and running back to the flames. It’s natural enough to have run, but there’s something the film doesn’t show. That was Chief Petty Officer Frederick “Bull” Tobin, the airship veteran in charge of the landing party, bellowing at his sailors above the roar of the flames. “Navy men, Stand fast! We’ve got to get those people out of there!” Tobin had survived the crash of the USS Shenandoah on September 4, 1923. He wasn’t about to abandon his post, even if it cost him his life. Tobin’s Navy men obeyed. That’s what you see when they turn and run back to the flames.

The Hindenburg disaster is sometimes compared with that of the Titanic, but there’s a common misconception that the former disaster was the more deadly of the two. In fact, 64% of the passengers and crew aboard the airship survived the fiery crash, despite having only seconds to react. In contrast, officers on board the Titanic had 2½ hours to evacuate, yet most of the lifeboats were launched from level decks with empty seats. Only 32% of Titanic passengers and crew survived the sinking. It’s estimated that an additional 500 lives could have been saved, had there been a more orderly, competent, evacuation of the ship.

As it was, 35 passengers and crew lost their lives on this day in 1937, and one civilian ground crew. Without doubt the number would have been higher, if not for the actions of Bull Tobin and is Navy men.

Where a person was inside the airship, had a lot to do with their chances of survival. Mr and Mrs Hermann Doehner and their three children (Irene, 16, Walter, 10, and Werner, 8) were in the dining room, watching the landing. Mr. Doehner left before the fire broke out. Mrs. Doehner and the two boys were able to jump out, but Irene went looking for her father. Both died in the crash.

Where a person was inside the airship, had a lot to do with their chances of survival. Mr and Mrs Hermann Doehner and their three children (Irene, 16, Walter, 10, and Werner, 8) were in the dining room, watching the landing. Mr. Doehner left before the fire broke out. Mrs. Doehner and the two boys were able to jump out, but Irene went looking for her father. Both died in the crash.

For all the film of the Hindenburg disaster, there is no footage showing the moment of ignition. Investigators theorized a loose cable creating a spark or static charge from the electrically charged atmosphere. Some believed the wreck to be the result of sabotage, but that theory is largely debunked.

Four score years after the disaster, the reigning hypothesis begins with the static electricity theory, the fire fed and magnified by the incendiary iron oxide/aluminum impregnated cellulose “dope” with which the highly flammable hydrogen envelope was painted.

The 35 year era of the dirigible was filled with accidents before Hindenburg, but none had dampened public enthusiasm for lighter-than-air travel. The British R-101 accident killed 48, the crash of the USS Akron 73. The LZ-4, LZ-5, Deutschland, Deutschland II, Italia, Schwaben, R-38, R-101, Shenandoah, Macon, and there were others. All had crashed, disappeared into the darkness, or over the ocean. Hindenburg alone was caught on film, the fiery crash recorded for all to see. The age of the dirigible, had come to an end.

Today the Exercise Tiger disaster is largely forgotten. Some have charged official cover-up, though information from SHAEF press releases appeared in the August edition of Stars & Stripes. At least three books contain the information. It seems more likely that the immediate need for secrecy and subsequent D-Day invasion swallowed the Tiger disaster, whole. History has a way of doing that.

Today the Exercise Tiger disaster is largely forgotten. Some have charged official cover-up, though information from SHAEF press releases appeared in the August edition of Stars & Stripes. At least three books contain the information. It seems more likely that the immediate need for secrecy and subsequent D-Day invasion swallowed the Tiger disaster, whole. History has a way of doing that.

One minute after declaring his “verbal shot” at the feds, Wardlow “surrendered” to a nearby naval officer, demanding a billion dollars in “foreign aid” in compensation for “the long federal siege.”

One minute after declaring his “verbal shot” at the feds, Wardlow “surrendered” to a nearby naval officer, demanding a billion dollars in “foreign aid” in compensation for “the long federal siege.”

Boston Patriots had been preparing for such an event. Sexton Robert John Newman and Captain John Pulling carried two lanterns to the steeple of the Old North church, signaling that the Regulars were crossing the Charles River to Cambridge. Dr. Joseph Warren ordered Paul Revere and Samuel Dawes to ride out and warn surrounding villages and towns, the two soon joined by a third rider, Samuel Prescott. It was Prescott alone who would make it as far as Concord, though hundreds of riders would fan out across the countryside before the night was through.

Boston Patriots had been preparing for such an event. Sexton Robert John Newman and Captain John Pulling carried two lanterns to the steeple of the Old North church, signaling that the Regulars were crossing the Charles River to Cambridge. Dr. Joseph Warren ordered Paul Revere and Samuel Dawes to ride out and warn surrounding villages and towns, the two soon joined by a third rider, Samuel Prescott. It was Prescott alone who would make it as far as Concord, though hundreds of riders would fan out across the countryside before the night was through.

Some British soldiers marched 35 miles over those two days, their final retreat coming under increasing attack from militia members firing from behind stone walls, buildings and trees. One taking up such a firing position was Samuel Whittemore of Menotomy Village, now Arlington Massachusetts. At 80 he was the oldest known combatant of the Revolution.

Some British soldiers marched 35 miles over those two days, their final retreat coming under increasing attack from militia members firing from behind stone walls, buildings and trees. One taking up such a firing position was Samuel Whittemore of Menotomy Village, now Arlington Massachusetts. At 80 he was the oldest known combatant of the Revolution.

Isoroku Takano was born in Niigata, the son of a middle-ranked samurai of the Nagaoka Domain. His first name “Isoroku”, translating as “56”, refers to his father’s age at the birth of his son. At this time, it was common practice that samurai families without sons would “adopt” suitable young men, in order to carry on the family name, rank, and the income that came with it. The young man so adopted would carry the family name. So it was that Isoroku Takano became Isoroku Yamamoto in 1916, at the age of 32.

Isoroku Takano was born in Niigata, the son of a middle-ranked samurai of the Nagaoka Domain. His first name “Isoroku”, translating as “56”, refers to his father’s age at the birth of his son. At this time, it was common practice that samurai families without sons would “adopt” suitable young men, in order to carry on the family name, rank, and the income that came with it. The young man so adopted would carry the family name. So it was that Isoroku Takano became Isoroku Yamamoto in 1916, at the age of 32.

Many believed that Yamamoto’s career was finished when his old adversary Hideki Tōjō ascended to the Prime Ministership in 1941. Yet there was none better to run the combined fleet. When the pro-war faction took control of the Japanese government, he bowed to the will of his superiors. It was Isoroku Yamamoto who was tasked with planning the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Many believed that Yamamoto’s career was finished when his old adversary Hideki Tōjō ascended to the Prime Ministership in 1941. Yet there was none better to run the combined fleet. When the pro-war faction took control of the Japanese government, he bowed to the will of his superiors. It was Isoroku Yamamoto who was tasked with planning the attack on Pearl Harbor. American carrier based Torpedo bombers were slaughtered in their attack, with 36 out of 42 shot down. Yet Japanese defenses had been caught off-guard, their carriers busy rearming and refueling planes when American dive-bombers arrived.

American carrier based Torpedo bombers were slaughtered in their attack, with 36 out of 42 shot down. Yet Japanese defenses had been caught off-guard, their carriers busy rearming and refueling planes when American dive-bombers arrived. Midway was a disaster for the Imperial Japanese navy. The carriers Akagi, Kaga, Soryu and Hiryu, the entire strength of the task force, went to the bottom. The Japanese also lost the heavy cruiser Mikuma, along with 344 aircraft and 5,000 sailors. Much has been made of the loss of Japanese aircrews at Midway, but two-thirds of them survived. The greater long term disaster, may have been the loss of all those trained aircraft mechanics and ground crew who went down with their carriers.

Midway was a disaster for the Imperial Japanese navy. The carriers Akagi, Kaga, Soryu and Hiryu, the entire strength of the task force, went to the bottom. The Japanese also lost the heavy cruiser Mikuma, along with 344 aircraft and 5,000 sailors. Much has been made of the loss of Japanese aircrews at Midway, but two-thirds of them survived. The greater long term disaster, may have been the loss of all those trained aircraft mechanics and ground crew who went down with their carriers. tour throughout the South Pacific. US naval intelligence intercepted and decoded his schedule. The order for “Operation Vengeance” went down the chain of command from President Roosevelt to Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox to Naval Operations Admiral Ernest King to Admiral Chester Nimitz at Pearl Harbor. Sixteen Lockheed P-38 Lightnings, the only fighters capable of the ranges involved, were dispatched from Guadalcanal on April 17 with the order: “Get Yamamoto”.

tour throughout the South Pacific. US naval intelligence intercepted and decoded his schedule. The order for “Operation Vengeance” went down the chain of command from President Roosevelt to Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox to Naval Operations Admiral Ernest King to Admiral Chester Nimitz at Pearl Harbor. Sixteen Lockheed P-38 Lightnings, the only fighters capable of the ranges involved, were dispatched from Guadalcanal on April 17 with the order: “Get Yamamoto”. intercepted over Rabaul on April 18, 1943. Knowing only that his target was “an important high value officer”, 1st Lieutenant Rex Barber opened up on the first Japanese transport until smoke billowed from its left engine. Yamamoto’s body was found in the wreckage the following day with a .50 caliber bullet wound in his shoulder, another in his head. He was dead before he hit the ground.

intercepted over Rabaul on April 18, 1943. Knowing only that his target was “an important high value officer”, 1st Lieutenant Rex Barber opened up on the first Japanese transport until smoke billowed from its left engine. Yamamoto’s body was found in the wreckage the following day with a .50 caliber bullet wound in his shoulder, another in his head. He was dead before he hit the ground.

Castro proclaimed his administration to be an example of “direct democracy”, and dismissed the need for elections. The Cuban people could assemble demonstrations and express their democratic will to him personally, he said. Who needs elections?

Castro proclaimed his administration to be an example of “direct democracy”, and dismissed the need for elections. The Cuban people could assemble demonstrations and express their democratic will to him personally, he said. Who needs elections?

Kennedy was finally persuaded to authorize unmarked US fighter jets from the aircraft carrier Essex to provide escort cover for the invasion’s B-26 bombers, most of which were flown by CIA personnel in support of the ground invasion. Fighters missed their rendezvous by an hour, due to a misunderstanding about time zones. Unescorted bombers are easy targets, and two of them were shot down with four Americans killed. Fighting ended on April 20, 1961 in what had become an unmitigated fiasco.

Kennedy was finally persuaded to authorize unmarked US fighter jets from the aircraft carrier Essex to provide escort cover for the invasion’s B-26 bombers, most of which were flown by CIA personnel in support of the ground invasion. Fighters missed their rendezvous by an hour, due to a misunderstanding about time zones. Unescorted bombers are easy targets, and two of them were shot down with four Americans killed. Fighting ended on April 20, 1961 in what had become an unmitigated fiasco.

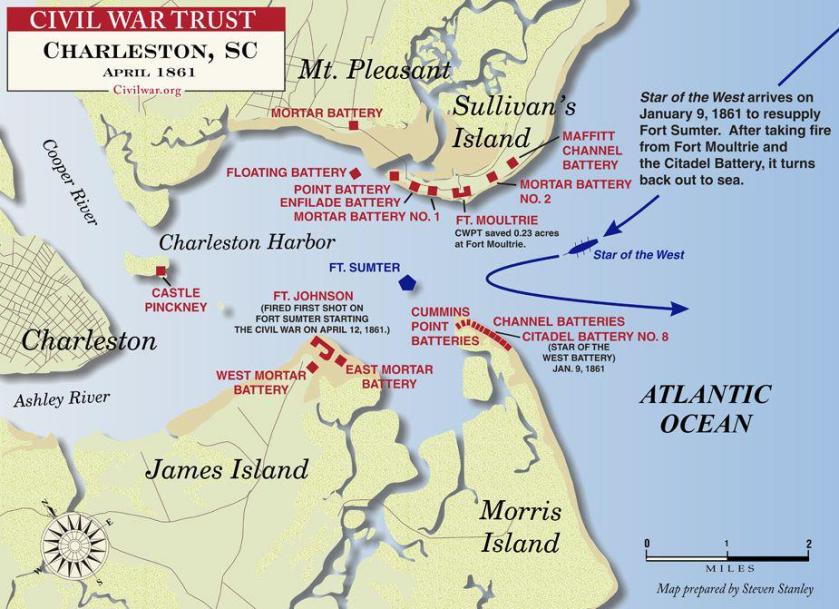

President James Buchanan attempted to reinforce and resupply Anderson, via the unarmed merchant vessel “Star of the West”. Shore batteries opened up on the effort on January 9, 1861, effectively trapping Anderson and his garrison inside the only federal property in the vicinity.

President James Buchanan attempted to reinforce and resupply Anderson, via the unarmed merchant vessel “Star of the West”. Shore batteries opened up on the effort on January 9, 1861, effectively trapping Anderson and his garrison inside the only federal property in the vicinity.

Charleston Mercury Newspaper, offered to personally eat the bodies of all the slain in the coming conflict. Not wanting to be outdone, former Senator James Chesnut, Jr. said “a lady’s thimble will hold all the blood that will be shed,” promising to personally drink any that might be spilled.

Charleston Mercury Newspaper, offered to personally eat the bodies of all the slain in the coming conflict. Not wanting to be outdone, former Senator James Chesnut, Jr. said “a lady’s thimble will hold all the blood that will be shed,” promising to personally drink any that might be spilled.

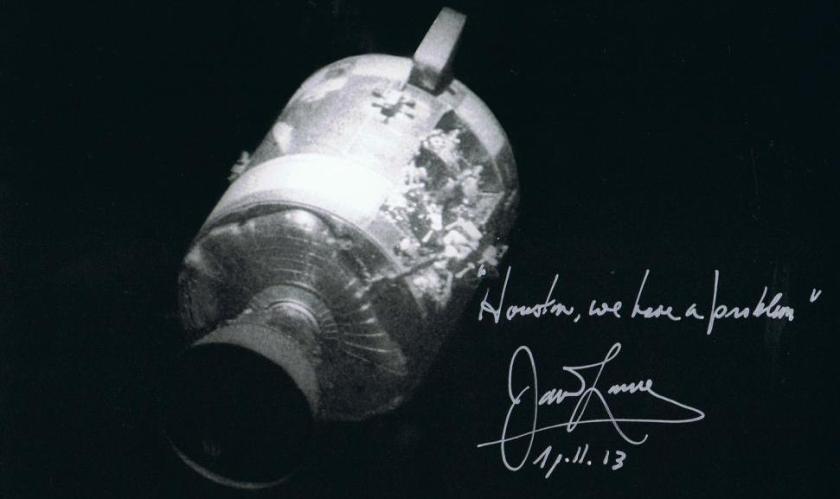

Jack Swigert was supposed to be the backup pilot for the Command Module, (CM), officially joining the Apollo 13 mission only 48 hours earlier, when prime crew member Ken Mattingly was exposed to German measles. Jim Lovell was the world’s most traveled astronaut, a veteran of two Gemini missions and Apollo 8. By launch day, April 11, 1970, Lovell had racked up 572 space flight hours. For Fred Haise, former backup crew member on Apollo 8 and 11, this would be his first spaceflight.

Jack Swigert was supposed to be the backup pilot for the Command Module, (CM), officially joining the Apollo 13 mission only 48 hours earlier, when prime crew member Ken Mattingly was exposed to German measles. Jim Lovell was the world’s most traveled astronaut, a veteran of two Gemini missions and Apollo 8. By launch day, April 11, 1970, Lovell had racked up 572 space flight hours. For Fred Haise, former backup crew member on Apollo 8 and 11, this would be his first spaceflight.

This situation had been suggested during an earlier training simulation, but had been considered unlikely. As it happened, the accident would have been fatal without access to the Lunar Module.

This situation had been suggested during an earlier training simulation, but had been considered unlikely. As it happened, the accident would have been fatal without access to the Lunar Module.

You must be logged in to post a comment.