Suppose you were to stop 100 randomly selected individuals on the street, and ask them:

“Of all the conflicts in American military history, which single battle accounts for the greatest loss of life“.

I suppose you’d get a few Gettysburgs in there, and maybe an Antietam or two. The Battle of the Bulge would come up, for sure, and there’s bound to be a Tarawa or an Iwo Jima. Maybe a Normandy.

I wonder how many would answer, Meuse-Argonne.

The United States arrived late to the “War End all Wars”, entering the conflict in April 1917 when President Woodrow Wilson asked permission of the Congress, for a declaration of war against Imperial Germany. American troop levels “over there” remained small throughout 1917, as the formerly neutral nation of fifty million ramped up to a war footing.

The trickle turned to a flood in 1918, as French ports were expanded to handle their numbers. The American Merchant Marine was insufficient to handle the influx, and received help from French and British vessels. By August, every one of what was then forty-eight states had sent armed forces, amounting to nearly 1½ million American troops in France.

After four years of unrelenting war, French and British manpower was staggered and the two economies, nearing collapse. Tens of thousands of German troops were freed up and moving to the western front, following the chaos of the Russian Revolution. The American Expeditionary Force was arriving none too soon.

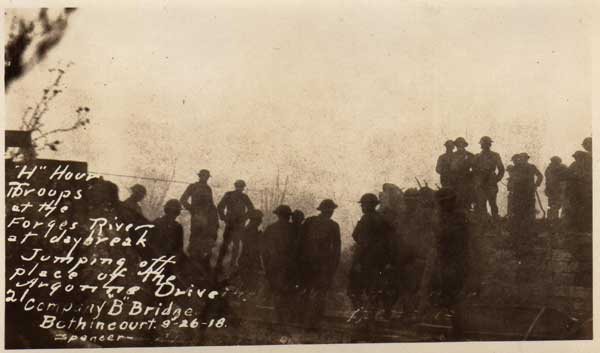

Following successful allied offensives at Amiens and Albert, Allied Supreme Commander Ferdinand Foch ordered General John J. “Black Jack” Pershing to take overall command of the offensive, with the objective of cutting off the German 2nd Army. Some 400,000 troops were moved into the Verdun sector of northeastern France. This was to be the largest operation of the AEF, of World War I. With a half-hour to go before midnight September 25, 2,700 guns opened up in a six hour bombardment, against German positions in the Argonne Forest, along the Meuse River.

Some 10,000 German troops were killed or incapacitated by mustard and phosgene gas attacks, and another 30,000 plus, taken prisoner. The Allied offensive advanced six miles into enemy territory, but bogged down in the wild woodlands and stony mountainsides of the Argonne Forest.

The Allied drive broke down on German strong points like the hilltop monastery at Montfaucon and others, and fortified positions of the German “defense in depth”.

Pershing called off the Meuse-Argonne offensive on September 30, as supplies and reinforcements backed up in what can only be termed the Mother of All Traffic Jams.

Fighting was renewed four days later resulting in some of the most famous episodes of WW1, including the “Lost Battalion” of Major Charles White Whittlesey, and the single-handed capture of 132 prisoners, by Corporal (and later Sergeant) Alvin York.

The Meuse-Argonne offensive lasted forty-seven days, resulting in 26,277 American women gaining that most exclusive and unwanted of distinctions. That of becoming a Gold Star Mother. More than any other battle, in American military history. 95,786 mothers would see their boys come home, mangled.

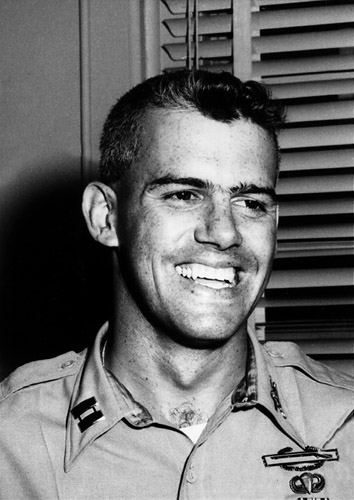

George Vaughn Seibold was born in the nation’s capital, Washington DC, At 23, Seibold volunteered when the US entered the war, in 1917. He requested a flying assignment and, as the US had no aerial force in the war at that time he was sent to Canada to be trained, on British aircraft.

He was assigned to the 148th Aero Squadron of the British Royal Flying Corps and sent off for combat, in France. George sent a regular stream of letters back home to his family. George’s mother grace Darling Siebold would do community service visiting wounded servicemen, in hospital.

And then one day, the letters stopped.

The Siebold family inquired but, as aviators were under British control US authorities, could be of little assistance. Grace continued to visit the maimed from the war “over there” but now in the vain hope that George might somehow appear, among them.

It wasn’t meant to be.

On October 11, 1918, George’s wife in Chicago, Catharine (Benson) Siebold received a box, marked “Effects of deceased Officer 1st Lt. George Vaughn Seibold”. The family later learned that George was killed in action over Baupaume, France, August 26, 1918. His body was never recovered.

Grace believed that grief turned inward was corrosive, and self destructive. She continued to visit the wounded but now she founded a group of other mothers, who had lost sons in military service. The group not only gave comfort to these women but an opportunity to reach out, and help the wounded. They named the organization after the gold star families hung in their windows, in honor of their dead.

On May 28, 1918, President Woodrow Wilson approved a suggestion from the Women’s Committee of the Council of National Defenses, that American women were asked to wear black bands on the left arm, with a gilt star for every family member who had given his life for the nation.

Today, Title 36 § 111 of the United States Code provides that the last Sunday in September be observed as Gold Star Mother’s Day, in honor of those women who have made the ultimate sacrifice. April 5 is set aside, as Gold Star Spouse’s Day.

In recent years both President Barack Obama and Donald Trump have signed proclamations, setting this day aside as Gold Star Mother’s and Family’s Day.

At first a distinction reserved only for those mothers who had lost sons and daughters in WW1, (272 U.S. Army nurses died of disease in the great War) that now includes a long list of conflicts, fought over the last 100 years. At this time the United States Army website reports “The Army is dedicated to providing ongoing support to over 78,000 surviving Family members of fallen Soldiers”.

Seventy-eight thousand, out of a nation of nearly 330 million. They are so few, who pick up this heaviest of tabs on behalf of the rest of us.

You must be logged in to post a comment.