If you’re ever in South Carolina, stop and enjoy the historical delights of the Pee Dee region. About a half-hour from Pedro’s “South of the Border”, there you will find the “All-American City” of Florence, according to the National Civic League of 1965. With a population of about 38,000, Florence describes itself as a regional center for business, medicine, culture and finance.

Oh. And the Federal Government dropped a Nuke on the place. Sixty-two years ago, today.

To anyone under the age of 40, the Cold War must seem a strange and incomprehensible time. Those of us who lived through it, feel the same way.

To anyone under the age of 40, the Cold War must seem a strange and incomprehensible time. Those of us who lived through it, feel the same way.

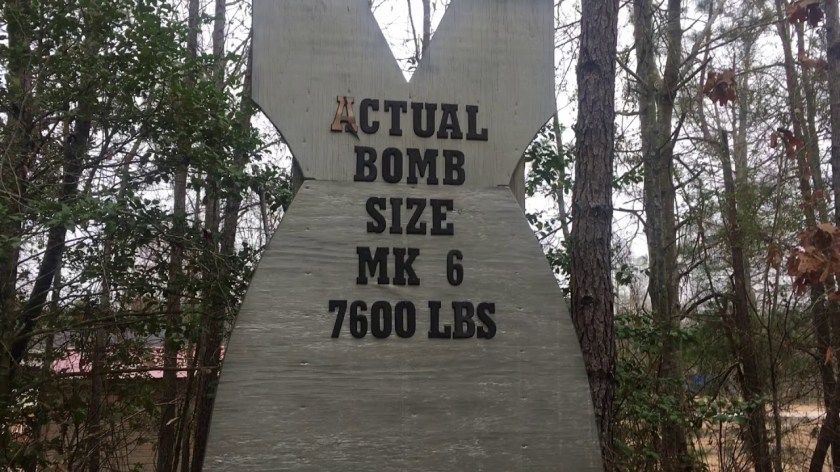

The Air Force Boeing Stratojet bomber left Hunter Air Force Base in Savannah, on a routine flight to Africa via the United Kingdom. Just in case thermonuclear war was to break out with the Soviet Union, the B47 carried a 10-foot 8-inch, 7,600-pound, Mark 4, atomic bomb.

The Atlantic Coastline Railroad conductor, WWII veteran & former paratrooper Walter Gregg Sr. was in the workshop next to his home in the Mars Bluff neighborhood of Florence, South Carolina while his wife, Ethel Mae “Effie” Gregg, was inside, sewing. The Gregg sisters Helen and Frances, ages 6 and 9, were playing in the woods with their nine-year-old cousin Ella Davies as the B47 Stratojet bomber lumbered overhead. At 15,000-feet, a warning light came on in the cockpit, indicating the load wasn’t properly secured. Not wanting a thing like that rattling around in the back, Captain Earl E. Koehler sent navigator Bruce M. Kulka, to investigate. Kulka slipped and grabbed out for something, to steady himself. That “something” just happened to be, the emergency release.

At 15,000-feet, a warning light came on in the cockpit, indicating the load wasn’t properly secured. Not wanting a thing like that rattling around in the back, Captain Earl E. Koehler sent navigator Bruce M. Kulka, to investigate. Kulka slipped and grabbed out for something, to steady himself. That “something” just happened to be, the emergency release.

Bomb bay doors alone are woefully inadequate to hold back a 4-ton bomb. The thing came free and began a 15,000-foot descent, straight into the Gregg’s back yard.

The Mark 4 atom bomb employs an IFI (in-flight insertion) safety, whereby composite uranium and plutonium fissile pits are inserted into the bomb core, thus arming the weapon. When deployed, a 6,000-pound. conventional explosion super-compresses the fissile core, beginning a nuclear chain reaction. In the first millisecond, (one millionth of a second), plasma expands to a size of several meters as temperatures rise into the tens of millions of degrees, Celsius. Thermal electromagnetic “Black-body” radiation in the X-Ray spectrum is absorbed into the surrounding air, producing a fireball. The kinetic energy imparted by the reaction produces an initial explosive force of about 7,500 miles, per second.

This particular nuke was unarmed that day but three tons of conventional explosives can ruin your whole day. The weapon scored a direct hit on a playhouse built for the Gregg children, the explosion leaving a crater 70-feet wide and 35-feet deep and destroying the Gregg home, the farmhouse, workshop and several outbuildings. Buildings within a five-mile radius were damaged, including a local church. Effie gashed her head when the walls blew in but miraculously, no one was killed except for a couple chickens. Not even the cat.

Three years later, a B-52 Stratofortress carrying two Mark 39 thermonuclear bombs broke up in the air over Goldsboro, North Carolina. Five crew members ejected from the aircraft at 9,000-feet and landed safely, another ejected but did not survive the landing. Two others died in the crash.

Three years later, a B-52 Stratofortress carrying two Mark 39 thermonuclear bombs broke up in the air over Goldsboro, North Carolina. Five crew members ejected from the aircraft at 9,000-feet and landed safely, another ejected but did not survive the landing. Two others died in the crash.

In this incident, both weapons were fully nuclear-enabled. A single switch out of four, is all that prevented at least one of the things, from going off.

Walter Gregg described the Mars Bluff incident in 2001, in director Peter Kuran’s documentary “Nuclear 911”. “It just came like a bolt of lightning”, he said. “Boom! And it was all over. The concussion …caved the roof in.” Left with little but the clothes on their backs, the Greggs eventually sued the Federal Government.

The family was awarded $36,000 by the United States Air force. It wasn’t enough to rebuild the house let alone, replace their possessions. Walter Gregg resented it, for the rest of his life.

Over the years, members of the flight crew stopped by to apologize for the episode.

Over the years, members of the flight crew stopped by to apologize for the episode.

The land remains in private hands but it’s federally protected, so it can’t be developed. They even made a path back in 2008 and installed a few signs, but those were mostly stolen by college kids.

You can check it out for yourself if you want to amuse the locals. They’ll know what you’re doing as soon as you drive through the neighborhood, the second time. Crater Rd/4776 Lucius Circle, Mars Bluff, SC (Hat tip roadsideamerica.com)

A month before the Mars Bluff incident, a hydrogen bomb was accidentally dropped in the ocean, off Tybee Island, Georgia. Incidents involving the loss or accidental detonation of nuclear weapons are called “Broken Arrows“. There have been 32 such incidents, since 1950. As of this date, six atomic weapons remain unaccounted for, including that one off the Georgia coast.

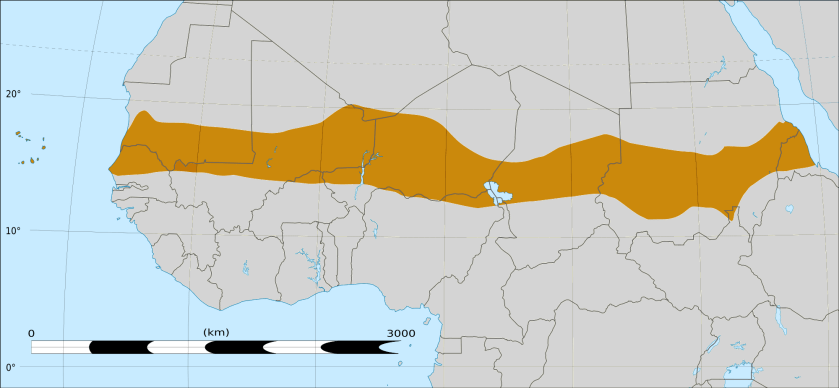

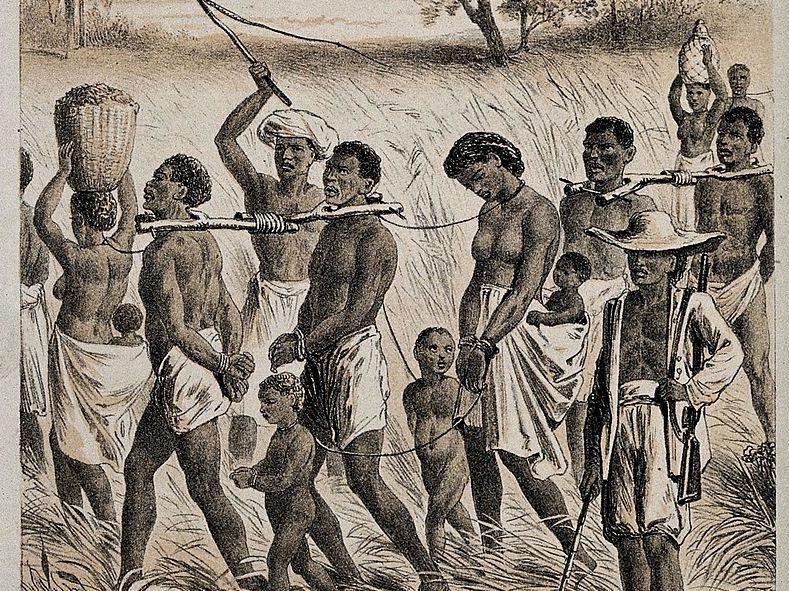

2,500 years ago, Bantu farmers on the African continent began to spread out across the land as the first Africans penetrated the dense rain forests of the equator, to take up a new life on the west African coast.

2,500 years ago, Bantu farmers on the African continent began to spread out across the land as the first Africans penetrated the dense rain forests of the equator, to take up a new life on the west African coast.

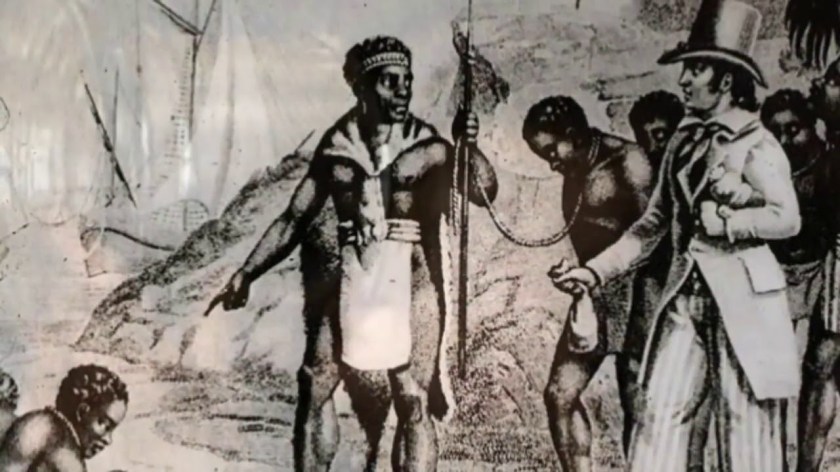

Home to one of the few safe harbors on the surf-battered “windward coast”, Sierra Leone soon became a favorite of European mariners, some of whom remained for a time while others came to stay, intermarrying with local women.

Home to one of the few safe harbors on the surf-battered “windward coast”, Sierra Leone soon became a favorite of European mariners, some of whom remained for a time while others came to stay, intermarrying with local women. While this type of “slave” retained rudimentary rights at this time, those unfortunate enough to be captured by Dutch, English and French slavers, did not.

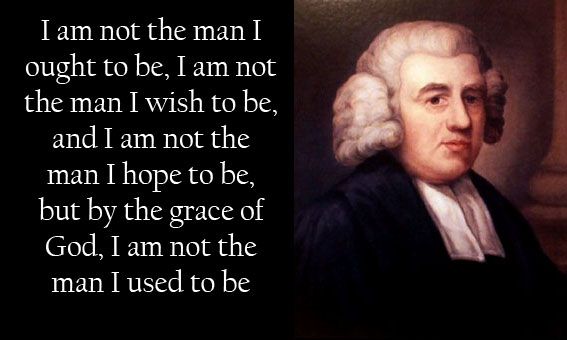

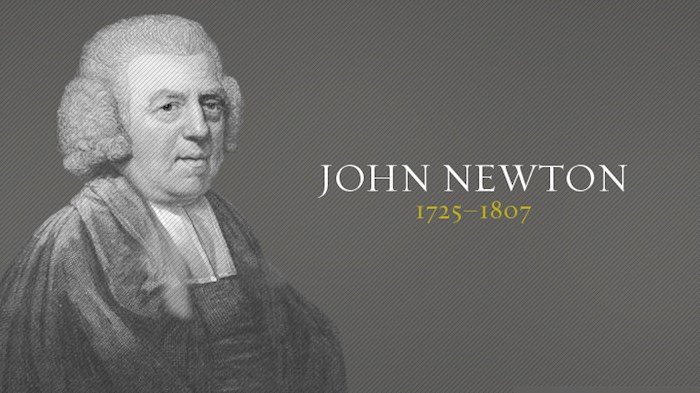

While this type of “slave” retained rudimentary rights at this time, those unfortunate enough to be captured by Dutch, English and French slavers, did not. This was the world of John Newton, born July 24 (old style) 1725 and destined to a life, in the slave trade.

This was the world of John Newton, born July 24 (old style) 1725 and destined to a life, in the slave trade. Newton hated life on the Pegasus as much as they, hated him. In 1745, they left him in West Africa with slave trader Amos Clowe. Newton was now himself a slave, given by Clowe to his wife Princess Peye of the Sherbro tribe. Peye treated Newton as horribly as any of her other slaves. Newton himself later described these three years as “once an infidel and a libertine, [now] a servant of slaves in West Africa”.

Newton hated life on the Pegasus as much as they, hated him. In 1745, they left him in West Africa with slave trader Amos Clowe. Newton was now himself a slave, given by Clowe to his wife Princess Peye of the Sherbro tribe. Peye treated Newton as horribly as any of her other slaves. Newton himself later described these three years as “once an infidel and a libertine, [now] a servant of slaves in West Africa”. Moving to London in 1780 as the Rector of St. Mary Woolnoth church, Newton became involved with the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

Moving to London in 1780 as the Rector of St. Mary Woolnoth church, Newton became involved with the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. William Cowper was an English poet and hymnist who came to worship in Newton’s church, in 1767. The pair collaborated on a book of Newton’s hymns including “Glorious Things of Thee Are Spoken,” “How Sweet the Name of Jesus Sounds!,” “Come, My Soul, Thy Suit Prepare” and others.

William Cowper was an English poet and hymnist who came to worship in Newton’s church, in 1767. The pair collaborated on a book of Newton’s hymns including “Glorious Things of Thee Are Spoken,” “How Sweet the Name of Jesus Sounds!,” “Come, My Soul, Thy Suit Prepare” and others.

Radios of the age didn’t work across the Rockies, and the mail was erratic. The only passenger service available was run by the Yukon Southern airline, a run which locals called the “Yukon Seldom”. For construction battalions at Dawson Creek, Delta Junction and Whitehorse, it was faster to talk to each other through military officials in Washington, DC.

Radios of the age didn’t work across the Rockies, and the mail was erratic. The only passenger service available was run by the Yukon Southern airline, a run which locals called the “Yukon Seldom”. For construction battalions at Dawson Creek, Delta Junction and Whitehorse, it was faster to talk to each other through military officials in Washington, DC. Tent pegs were useless in the permafrost, while the body heat of sleeping soldiers meant waking up in mud. Partially thawed lakes meant that supply planes could use neither pontoon nor ski, as Black flies swarmed the troops by day. Hungry bears raided camps at night, looking for food.

Tent pegs were useless in the permafrost, while the body heat of sleeping soldiers meant waking up in mud. Partially thawed lakes meant that supply planes could use neither pontoon nor ski, as Black flies swarmed the troops by day. Hungry bears raided camps at night, looking for food. That October, Refines Sims Jr. of Philadelphia, with the all-black 97th Engineers, was driving a bulldozer 20 miles east of the Alaska-Yukon line when the trees in front of him toppled to the ground. Sims slammed his machine into reverse as a second bulldozer came into view, driven by Kennedy, Texas Private Alfred Jalufka. North had met south, and the two men jumped off their machines, grinning. Their triumphant handshake was photographed by a fellow soldier and published in newspapers across the country, becoming an unintended first step toward desegregating the US military.

That October, Refines Sims Jr. of Philadelphia, with the all-black 97th Engineers, was driving a bulldozer 20 miles east of the Alaska-Yukon line when the trees in front of him toppled to the ground. Sims slammed his machine into reverse as a second bulldozer came into view, driven by Kennedy, Texas Private Alfred Jalufka. North had met south, and the two men jumped off their machines, grinning. Their triumphant handshake was photographed by a fellow soldier and published in newspapers across the country, becoming an unintended first step toward desegregating the US military.

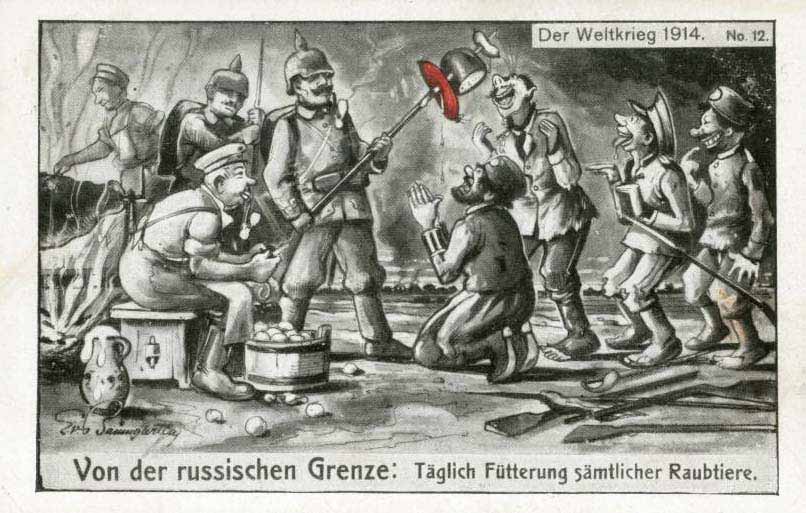

By 1916 it was generally understood in Germany that the war effort was “shackled to a corpse”, referring the Austro-Hungarian Empire where the war had started, in the first place. Italy, the third member of the “Triple Alliance”, was little better. On the “Triple Entente” side, the French countryside was literally torn to pieces, the English economy close to collapse. The Russian Empire, the largest nation on the planet, was teetering on the edge of the precipice.

By 1916 it was generally understood in Germany that the war effort was “shackled to a corpse”, referring the Austro-Hungarian Empire where the war had started, in the first place. Italy, the third member of the “Triple Alliance”, was little better. On the “Triple Entente” side, the French countryside was literally torn to pieces, the English economy close to collapse. The Russian Empire, the largest nation on the planet, was teetering on the edge of the precipice.

By October, Russia would experience its second revolution of the year. The German Empire could breathe easier. The “Russian Steamroller” was out of the war. And none too soon, too. With the Americans entering the war that April, Chief of the General Staff Paul von Hindenburg and his deputy Erich Ludendorff could now move their divisions westward, in time to face the arrival of the American Expeditionary Force.

By October, Russia would experience its second revolution of the year. The German Empire could breathe easier. The “Russian Steamroller” was out of the war. And none too soon, too. With the Americans entering the war that April, Chief of the General Staff Paul von Hindenburg and his deputy Erich Ludendorff could now move their divisions westward, in time to face the arrival of the American Expeditionary Force.

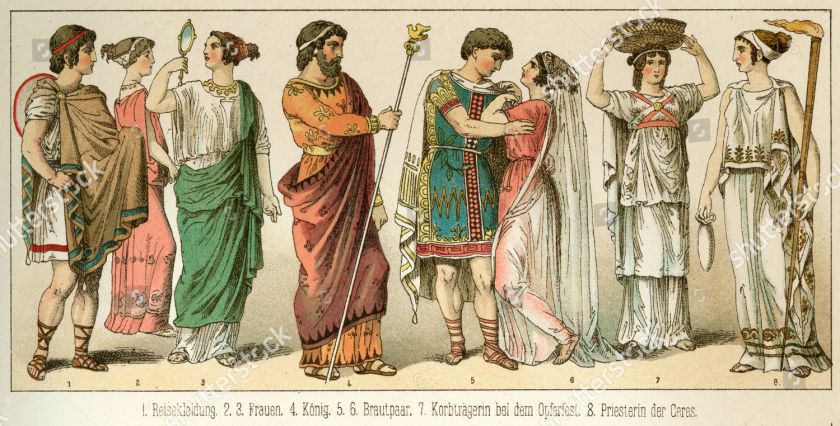

Be that as it may, three things are certain. First, The fire burned for six days, utterly destroying three of the 14 districts of Rome and severely damaging seven others. Second, Nero used the excuse of the fire to go after Christians, having many of them arrested and executed. Third, the Domus Aurea (“Golden Palace”) and surrounding “Pleasure Gardens” emperor Nero built on the ruins, would be the death of him.

Be that as it may, three things are certain. First, The fire burned for six days, utterly destroying three of the 14 districts of Rome and severely damaging seven others. Second, Nero used the excuse of the fire to go after Christians, having many of them arrested and executed. Third, the Domus Aurea (“Golden Palace”) and surrounding “Pleasure Gardens” emperor Nero built on the ruins, would be the death of him.

Within forty years, most of the grounds were filled with earth and built over, replaced by the Baths of Titus and the Temple of Venus and Rome. Vespasian drained the lake and built the Flavian Amphitheatre.

Within forty years, most of the grounds were filled with earth and built over, replaced by the Baths of Titus and the Temple of Venus and Rome. Vespasian drained the lake and built the Flavian Amphitheatre. The Arch of Constantine, the last and largest of the Triumphal Arches of Rome and dedicated in AD315, was carefully positioned to align with Sol Invictus, so that the Colossus formed the dominant backdrop when approaching the Colosseum via the main arch.

The Arch of Constantine, the last and largest of the Triumphal Arches of Rome and dedicated in AD315, was carefully positioned to align with Sol Invictus, so that the Colossus formed the dominant backdrop when approaching the Colosseum via the main arch.

Dr. Emerson died in 1842, leaving his estate to his wife Eliza, who continued to lease the Scotts out as hired slaves.

Dr. Emerson died in 1842, leaving his estate to his wife Eliza, who continued to lease the Scotts out as hired slaves.

The fifty gun HMS Romney arrived in May, 1769. Customs officials seized John Hancock’s merchant sloop “Liberty” the following month, on allegations the vessel was involved in smuggling. Already agitated over Romney’s impressment of local sailors, Bostonians began to riot. By October, the first of four regular British army regiments arrived in Boston.

The fifty gun HMS Romney arrived in May, 1769. Customs officials seized John Hancock’s merchant sloop “Liberty” the following month, on allegations the vessel was involved in smuggling. Already agitated over Romney’s impressment of local sailors, Bostonians began to riot. By October, the first of four regular British army regiments arrived in Boston. Edward Garrick was a wigmaker’s apprentice, who worked each day to grease and powder and curl the long hair of the soldier’s wigs.

Edward Garrick was a wigmaker’s apprentice, who worked each day to grease and powder and curl the long hair of the soldier’s wigs. The two sides stopped for a few seconds to two minutes, depending on the witness. Then they all fired. A ragged, ill-disciplined volley. There was no order, just the flash and roar of gunpowder on the cold late afternoon streets of a Winter’s day. It was March 5. When the smoke cleared, three were dead. Two more lay mortally wounded and another six, seriously injured.

The two sides stopped for a few seconds to two minutes, depending on the witness. Then they all fired. A ragged, ill-disciplined volley. There was no order, just the flash and roar of gunpowder on the cold late afternoon streets of a Winter’s day. It was March 5. When the smoke cleared, three were dead. Two more lay mortally wounded and another six, seriously injured.

Those first ten years of independence was a time of increasing unrest for the American’s French ally, of the late revolution. The famous

Those first ten years of independence was a time of increasing unrest for the American’s French ally, of the late revolution. The famous

Napoleon Bonaparte, crowned Emperor the following year, would fight (and win) more battles than Julius Caesar, Hannibal, Alexander the Great and Frederick the Great, combined.

Napoleon Bonaparte, crowned Emperor the following year, would fight (and win) more battles than Julius Caesar, Hannibal, Alexander the Great and Frederick the Great, combined. Jean-Simon Chaudron founded the Abeille Américaine in 1815 (The American Bee), Philadelphia’s leading French language newspaper. Himself a refugee of Santo Domingo (Saint-Domingue), Chaudron catered to French merchants, emigres and former military figures of the Napoleonic era and the Haitian revolution.

Jean-Simon Chaudron founded the Abeille Américaine in 1815 (The American Bee), Philadelphia’s leading French language newspaper. Himself a refugee of Santo Domingo (Saint-Domingue), Chaudron catered to French merchants, emigres and former military figures of the Napoleonic era and the Haitian revolution. In January 1817, the Society for the Vine and Olive selected a site near the Tombigbee and Black Warrior Rivers in west-central Alabama, on former Choctaw lands. On March 3, 1817, Congress passed an act “disposing of a tract of land to embrace four townships, on favorable terms to the emigrants, to enable them successfully to introduce the cultivation of the vine and olive.”

In January 1817, the Society for the Vine and Olive selected a site near the Tombigbee and Black Warrior Rivers in west-central Alabama, on former Choctaw lands. On March 3, 1817, Congress passed an act “disposing of a tract of land to embrace four townships, on favorable terms to the emigrants, to enable them successfully to introduce the cultivation of the vine and olive.” General Charles Lallemand, who joined the French army in 1791, replaced Lefebvre-Desnouettes as President of the Colonial Society. A man better suited to the life of an adventurer than that of the plow, Lallemand was more interested in the wars of Latin American independence, than grapes and olives. By the fall of 1817, Lallemand and 69 loyalists had concocted a plan to sell the land they hadn’t yet paid for, to raise funds for the invasion of Texas.

General Charles Lallemand, who joined the French army in 1791, replaced Lefebvre-Desnouettes as President of the Colonial Society. A man better suited to the life of an adventurer than that of the plow, Lallemand was more interested in the wars of Latin American independence, than grapes and olives. By the fall of 1817, Lallemand and 69 loyalists had concocted a plan to sell the land they hadn’t yet paid for, to raise funds for the invasion of Texas. Little is left of the Vine and Olive Colony but the French Emperor lives on, in western Alabama. Marengo County commemorates Napoleon’s June 14, 1800 victory over Austrian forces at the Battle of Marengo. The county seat, also known as Marengo, was later renamed Linden. Shortened from the Napoleonic victory over Bavarian forces led by Archduke John of Austria, at the 1800 battle of Hohenlinden.

Little is left of the Vine and Olive Colony but the French Emperor lives on, in western Alabama. Marengo County commemorates Napoleon’s June 14, 1800 victory over Austrian forces at the Battle of Marengo. The county seat, also known as Marengo, was later renamed Linden. Shortened from the Napoleonic victory over Bavarian forces led by Archduke John of Austria, at the 1800 battle of Hohenlinden.

Captain Henry Wirz, commandant of the stockade at Camp Sumter, was tried and executed after the war, only one of two men to be hanged for war crimes. Captain Wirz appeared at trial reclined on a couch, advanced gangrene preventing him from sitting up. To some, the man was a scapegoat. A victim of circumstances beyond his control. To others he is a demon, personally responsible for the hell of Andersonville prison.

Captain Henry Wirz, commandant of the stockade at Camp Sumter, was tried and executed after the war, only one of two men to be hanged for war crimes. Captain Wirz appeared at trial reclined on a couch, advanced gangrene preventing him from sitting up. To some, the man was a scapegoat. A victim of circumstances beyond his control. To others he is a demon, personally responsible for the hell of Andersonville prison.

16th century Church doctrine taught that the Saints built a surplus of good works over a lifetime, sort of a moral bank account. Like “carbon credits” today, positive acts of faith and charity could expiate sin. Monetary contributions to the church could, so it was believed, “buy” the benefits of the saint’s good works, for the sinner.

16th century Church doctrine taught that the Saints built a surplus of good works over a lifetime, sort of a moral bank account. Like “carbon credits” today, positive acts of faith and charity could expiate sin. Monetary contributions to the church could, so it was believed, “buy” the benefits of the saint’s good works, for the sinner. A popular story has Martin Luther nailing the document to the door of the Wittenberg Palace Church, but it may never have happened that way. Luther had no intention of confronting the Church at this time. This was an academic work, 95 topics offered for scholarly debate.

A popular story has Martin Luther nailing the document to the door of the Wittenberg Palace Church, but it may never have happened that way. Luther had no intention of confronting the Church at this time. This was an academic work, 95 topics offered for scholarly debate. Luther stood on dangerous ground. Jan Hus had been burned at the stake for such heresy, back in 1415. On this day in 1420, Pope Martinus I called for a crusade against the followers of the Czech priest, the “Hussieten”.

Luther stood on dangerous ground. Jan Hus had been burned at the stake for such heresy, back in 1415. On this day in 1420, Pope Martinus I called for a crusade against the followers of the Czech priest, the “Hussieten”. The papal bull had the effect of hardening Luther’s positions. He publicly burned it, on December 10. Twenty-four days later, Luther was excommunicated. A general assembly of the secular authorities of the Holy Roman Empire summoned Luther to appear before them in April, in the upper-Rhine city of Worms. The “Edict of Worms” of May 25, 1521, declared Luther an outlaw, stating “We want him to be apprehended and punished as a notorious heretic”. Anyone killing Luther was permitted to do so without legal consequence.

The papal bull had the effect of hardening Luther’s positions. He publicly burned it, on December 10. Twenty-four days later, Luther was excommunicated. A general assembly of the secular authorities of the Holy Roman Empire summoned Luther to appear before them in April, in the upper-Rhine city of Worms. The “Edict of Worms” of May 25, 1521, declared Luther an outlaw, stating “We want him to be apprehended and punished as a notorious heretic”. Anyone killing Luther was permitted to do so without legal consequence.

You must be logged in to post a comment.