When he was little, his neighbors must have considered him a bad kid. His first arrest came at the age of 12, when he and some friends were caught stealing brass from a foundry. There were other episodes between 1932 and ’37: petty theft, breaking & entering, and disturbing the peace. In 1939 he was sent to prison, for stealing a car.

Edward Donald “Eddie” Slovik was paroled in 1942, his criminal record making him 4F. “Registrant not acceptable for military service”. He took a job at the Montella Plumbing and Heating company in Dearborn, Michigan, where he met bookkeeper Antoinette Wisniewski, the woman who would later become his wife.

Edward Donald “Eddie” Slovik was paroled in 1942, his criminal record making him 4F. “Registrant not acceptable for military service”. He took a job at the Montella Plumbing and Heating company in Dearborn, Michigan, where he met bookkeeper Antoinette Wisniewski, the woman who would later become his wife.

There they might have ridden out WWII, but the war was consuming manpower at a rate unprecedented in history. Shortly after the couple’s first anniversary, Slovik was re-classified 1A, fit for service, and drafted into the Army. Arriving in France on August 20, 1944, he was part of a 12-man replacement detachment, assigned to Company G of the 109th Infantry Regiment, US 28th Infantry Division.

Slovik and a buddy from basic training, Private John Tankey, became separated from their detachment during an artillery attack, and spent the next six weeks with Canadian MPs. It was around this time that Private Slovik decided he “wasn’t cut out for combat”.

The rapid movement of the army during this period caused many replacements difficulty in finding their units. Edward Slovik and John Tankey finally caught up with the 109th on October 7. The following day, Slovik asked his company commander Captain Ralph Grotte for reassignment to a rear unit, saying he was “too scared” to be part of a rifle company. Grotte refused, confirming that, were he to run away, such an act would constitute desertion.

That, he did. Eddie Slovik deserted his unit on October 9, despite Private Tankey’s protestations that he should stay. “My mind is made up”, he said. Slovik walked several miles until he found an enlisted cook, to whom he presented the following note.

“I, Pvt. Eddie D. Slovik, 36896415, confess to the desertion of the United States Army. At the time  of my desertion we were in Albuff [Elbeuf] in France. I came to Albuff as a replacement. They were shelling the town and we were told to dig in for the night. The following morning they were shelling us again. I was so scared, nerves and trembling, that at the time the other replacements moved out, I couldn’t move. I stayed there in my fox hole till it was quiet and I was able to move. I then walked into town. Not seeing any of our troops, so I stayed over night at a French hospital. The next morning I turned myself over to the Canadian Provost Corp. After being with them six weeks I was turned over to American M.P. They turned me loose. I told my commanding officer my story. I said that if I had to go out there again I’d run away. He said there was nothing he could do for me so I ran away again AND I’LL RUN AWAY AGAIN IF I HAVE TO GO OUT THERE. — Signed Pvt. Eddie D. Slovik A.S.N. 36896415”.

of my desertion we were in Albuff [Elbeuf] in France. I came to Albuff as a replacement. They were shelling the town and we were told to dig in for the night. The following morning they were shelling us again. I was so scared, nerves and trembling, that at the time the other replacements moved out, I couldn’t move. I stayed there in my fox hole till it was quiet and I was able to move. I then walked into town. Not seeing any of our troops, so I stayed over night at a French hospital. The next morning I turned myself over to the Canadian Provost Corp. After being with them six weeks I was turned over to American M.P. They turned me loose. I told my commanding officer my story. I said that if I had to go out there again I’d run away. He said there was nothing he could do for me so I ran away again AND I’LL RUN AWAY AGAIN IF I HAVE TO GO OUT THERE. — Signed Pvt. Eddie D. Slovik A.S.N. 36896415”.

Slovik was repeatedly ordered to tear up the note and rejoin his unit, and there would be no consequences. Each time, he refused. The stockade didn’t scare him. He’d been in prison before, and it was better than the front lines. Beside that, he was already an ex-con. A dishonorable discharge was hardly going to change anything, in a life he expected to be filled with manual labor. Finally, instructed to write a second note on the back of the first acknowledging the legal consequences of his actions, Eddie Slovik was taken into custody.

1.7 million courts-martial were held during WWII, 1/3rd of all the criminal cases tried in the United States during the same period. The death penalty was rarely imposed. When it was, it was almost always in cases of rape or murder.

2,864 US Army personnel were tried for desertion between January 1942 and June 1948. Courts-martial handed down death sentences to 49 of them, including Eddie Slovik. Division commander Major General Norman Cota approved the sentence. “Given the situation as I knew it in November, 1944,” he said, “I thought it was my duty to this country to approve that sentence. If I hadn’t approved it–if I had let Slovik accomplish his purpose–I don’t know how I could have gone up to the line and looked a good soldier in the face.”

On December 9, Slovik wrote to Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower, pleading for clemency. Desertion was a systemic problem at this time. Particularly after the surprise German offensive coming out of the frozen Ardennes Forest on December 16, an action that went into history as the Battle of the Bulge. Eisenhower approved the execution order on December 23, believing it to be the only way to discourage further desertions.

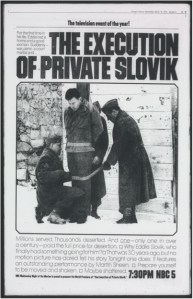

His uniform stripped of all insignia with an army blanket draped over his shoulders, Slovik was brought to the place of execution near the Vosges Mountains of France. “They’re not shooting me for deserting the United States Army”, he said, “thousands of guys have done that. They just need to make an example out of somebody and I’m it because I’m an ex-con. I used to steal things when I was a kid, and that’s what they are shooting me for. They’re shooting me for the bread and chewing gum I stole when I was 12 years old.”

Army Chaplain Father Carl Patrick Cummings said, “Eddie, when you get up there, say a little prayer for me.” Slovik said, “Okay, Father. I’ll pray that you don’t follow me too soon”. Those were his last words. A soldier placed the black hood over his head. The execution was carried out by firing squad. It was 10:04am local time, January 31, 1945.

Edward Donald Slovik was buried in Plot E of the Oise-Aisne American Cemetery, his marker bearing a number instead of his name. Antoinette Slovik received a telegram informing her that her husband had died in the European Theater of war, and a letter instructing her to return a $55 allotment check. She would not learn about the execution for nine years.

In 1987, President Ronald Reagan ordered the repatriation of Slovik’s remains. He was re-interred at Detroit’s Woodmere Cemetery next to Antoinette, who had gone to her final rest eight years earlier.

In 1987, President Ronald Reagan ordered the repatriation of Slovik’s remains. He was re-interred at Detroit’s Woodmere Cemetery next to Antoinette, who had gone to her final rest eight years earlier.

In all theaters of WWII, the United States military executed 102 of its own, almost always for the unprovoked rape and/or murder of civilians. From the Civil War to this day, Eddie Slovik’s death sentence remains the only one ever carried out for the crime of desertion. At least one member of the tribunal which condemned him to death, would come to see it as a miscarriage of justice.

Nick Gozik of Pittsburg passed away in 2015, at the age of 95. He was there in 1945, a fellow soldier called to witness the execution. “Justice or legal murder”, he said, “I don’t know, but I want you to know I think he was the bravest man in that courtyard that day…All I could see was a young soldier, blond-haired, walking as straight as a soldier ever walked. I thought he was the bravest soldier I ever saw.”

“I beg to ask the steps of that process”, asked Yen Yüan. The Master replied, “Look not at what is contrary to propriety. Listen not to what is contrary to propriety. Speak not what is contrary to propriety. Make no movement which is contrary to propriety”.

“I beg to ask the steps of that process”, asked Yen Yüan. The Master replied, “Look not at what is contrary to propriety. Listen not to what is contrary to propriety. Speak not what is contrary to propriety. Make no movement which is contrary to propriety”.

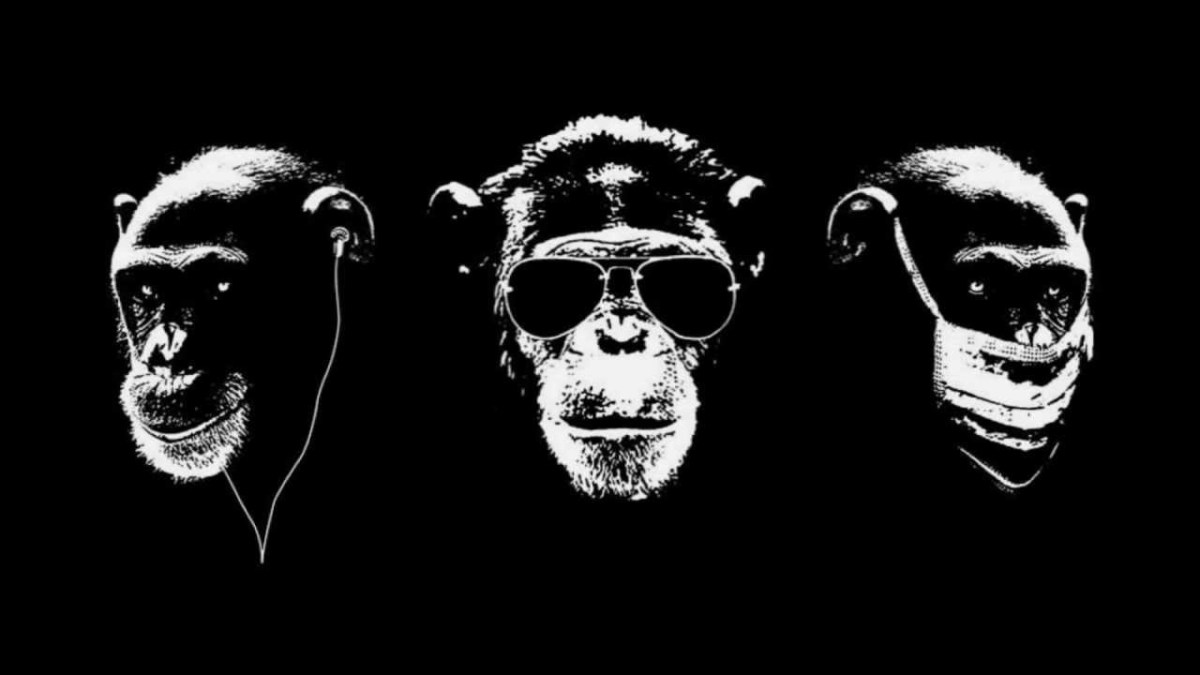

the Sanskrit “high-souled”, or “venerable”. He is recognized as the Father of modern India, who brought Independence to his country through non-violent protest. Gandhi lived a life of poverty and simplicity, owning almost no material possessions at the time of his assassination by a Hindu nationalist on January 30, 1948. Beside the clothes on his back, Gandhi owned a tin cup and a spoon, a pair of sandals, his spectacles, and a carved set of 3 monkeys, reminding him to hear no evil, see no evil and speak no evil.

the Sanskrit “high-souled”, or “venerable”. He is recognized as the Father of modern India, who brought Independence to his country through non-violent protest. Gandhi lived a life of poverty and simplicity, owning almost no material possessions at the time of his assassination by a Hindu nationalist on January 30, 1948. Beside the clothes on his back, Gandhi owned a tin cup and a spoon, a pair of sandals, his spectacles, and a carved set of 3 monkeys, reminding him to hear no evil, see no evil and speak no evil.

be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness”.

be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness”.

was obliged to render aid in the event that either ally was attacked. On December 8, 1941, the day after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Ambassador Hiroshi Ōshima came to Joachim von Ribbentrop, looking for a commitment of support from the German Foreign Minister.

was obliged to render aid in the event that either ally was attacked. On December 8, 1941, the day after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Ambassador Hiroshi Ōshima came to Joachim von Ribbentrop, looking for a commitment of support from the German Foreign Minister. 48 days later, at Hunter Field in Savannah, the Eighth Bomber Command was activated as part of the United States Army Air Forces. It was January 28, 1942.

48 days later, at Hunter Field in Savannah, the Eighth Bomber Command was activated as part of the United States Army Air Forces. It was January 28, 1942. Re-designated the Eighth Air Force on February 22, 1944, at its peak the “Mighty Eighth” could dispatch over 2,000 four engine bombers and more than 1,000 fighters on a single mission. 350,000 people served in the 8th AF during the war in Europe, with 200,000 at its peak in 1944.

Re-designated the Eighth Air Force on February 22, 1944, at its peak the “Mighty Eighth” could dispatch over 2,000 four engine bombers and more than 1,000 fighters on a single mission. 350,000 people served in the 8th AF during the war in Europe, with 200,000 at its peak in 1944.

1942 was a bad year for the allied war in the Pacific. The Battle of Bataan alone resulted in 72,000 prisoners being taken by the Japanese, marched off to POW camps designed for 10,000 to 25,000.

1942 was a bad year for the allied war in the Pacific. The Battle of Bataan alone resulted in 72,000 prisoners being taken by the Japanese, marched off to POW camps designed for 10,000 to 25,000.

Joining the 3rd Infantry Division of George S. Patton’s 7th Army, Murphy participated in amphibious landings in Sicily in July, fighting in nearly every aspect of the Italian campaign. From Palermo to Messina and on to Naples, Anzio and Rome, the Germans were driven out of the Italian peninsula in savage and near continuous fighting that killed a member of my own family. By mid-December, the 3rd ID suffered 683 dead, 170 missing, and 2,412 wounded. Now Sergeant Murphy was there for most of it, excepting two periods when he was down with malaria.

Joining the 3rd Infantry Division of George S. Patton’s 7th Army, Murphy participated in amphibious landings in Sicily in July, fighting in nearly every aspect of the Italian campaign. From Palermo to Messina and on to Naples, Anzio and Rome, the Germans were driven out of the Italian peninsula in savage and near continuous fighting that killed a member of my own family. By mid-December, the 3rd ID suffered 683 dead, 170 missing, and 2,412 wounded. Now Sergeant Murphy was there for most of it, excepting two periods when he was down with malaria. “Colmar Pocket” was an 850 square mile area held by German troops: Murphy described it as “a huge and dangerous bridgehead thrusting west of the Rhine like an iron fist. Fed with men and materiel from across the river, it is a constant threat to our right flank; and potentially it is a perfect springboard from which the enemy could start a powerful counterattack.”

“Colmar Pocket” was an 850 square mile area held by German troops: Murphy described it as “a huge and dangerous bridgehead thrusting west of the Rhine like an iron fist. Fed with men and materiel from across the river, it is a constant threat to our right flank; and potentially it is a perfect springboard from which the enemy could start a powerful counterattack.” Let Murphy’s Medal of Honor Citation describe what happened next: “Second Lieutenant Audie L. Murphy, 01692509, 15th Infantry, Army of the United States, on 26 January 1945, near Holtzwihr, France, commanded Company B, which was attacked by six tanks and waves of infantry. Lieutenant Murphy ordered his men to withdraw to a prepared position in a woods while he remained forward at his command post and continued to give fire directions to the artillery by telephone. Behind him to his right one of our tank destroyers received a direct hit and began to burn. Its crew withdrew to the woods. Lieutenant Murphy continued to direct artillery fire which killed large numbers of the advancing enemy infantry. With the enemy tanks abreast of his position, Lieutenant Murphy climbed on the burning tank destroyer which was in danger of blowing up any instant and employed its .50 caliber machine gun against the enemy. He was alone and exposed to the German fire from three sides, but his deadly fire killed dozens of Germans and caused their infantry attack to waver. The enemy tanks, losing infantry support, began to fall back. For an hour the Germans tried every available weapon to eliminate Lieutenant Murphy, but he continued to hold his position and wiped out a squad which was trying to creep up unnoticed on his right flank. Germans reached as close as 10 yards only to be mowed down by his fire. He received a leg wound but ignored it and continued the single-handed fight until his ammunition was exhausted. He then made his way to his company, refused medical attention, and organized the company in a counterattack which forced the Germans to withdraw. His directing of artillery fire wiped out many of the enemy; he personally killed or wounded about 50. Lieutenant Murphy’s indomitable courage and his refusal to give an inch of ground saved his company from possible encirclement and destruction and enabled it to hold the woods which had been the enemy’s objective”.

Let Murphy’s Medal of Honor Citation describe what happened next: “Second Lieutenant Audie L. Murphy, 01692509, 15th Infantry, Army of the United States, on 26 January 1945, near Holtzwihr, France, commanded Company B, which was attacked by six tanks and waves of infantry. Lieutenant Murphy ordered his men to withdraw to a prepared position in a woods while he remained forward at his command post and continued to give fire directions to the artillery by telephone. Behind him to his right one of our tank destroyers received a direct hit and began to burn. Its crew withdrew to the woods. Lieutenant Murphy continued to direct artillery fire which killed large numbers of the advancing enemy infantry. With the enemy tanks abreast of his position, Lieutenant Murphy climbed on the burning tank destroyer which was in danger of blowing up any instant and employed its .50 caliber machine gun against the enemy. He was alone and exposed to the German fire from three sides, but his deadly fire killed dozens of Germans and caused their infantry attack to waver. The enemy tanks, losing infantry support, began to fall back. For an hour the Germans tried every available weapon to eliminate Lieutenant Murphy, but he continued to hold his position and wiped out a squad which was trying to creep up unnoticed on his right flank. Germans reached as close as 10 yards only to be mowed down by his fire. He received a leg wound but ignored it and continued the single-handed fight until his ammunition was exhausted. He then made his way to his company, refused medical attention, and organized the company in a counterattack which forced the Germans to withdraw. His directing of artillery fire wiped out many of the enemy; he personally killed or wounded about 50. Lieutenant Murphy’s indomitable courage and his refusal to give an inch of ground saved his company from possible encirclement and destruction and enabled it to hold the woods which had been the enemy’s objective”. Hollywood and, until his death in a plane crash in 1971, his post-war life was never free of it.

Hollywood and, until his death in a plane crash in 1971, his post-war life was never free of it.

with what he first diagnosed as tonsillitis. More came down with sore throats, early sufferers beginning to die as Welch observed the white pseudo membrane of diphtheria. He had ordered fresh antitoxin the year before, but the shipment hadn’t arrived by the time the ports froze over. By January, all the serum in Nome was expired.

with what he first diagnosed as tonsillitis. More came down with sore throats, early sufferers beginning to die as Welch observed the white pseudo membrane of diphtheria. He had ordered fresh antitoxin the year before, but the shipment hadn’t arrived by the time the ports froze over. By January, all the serum in Nome was expired. The 300,000 units shipped as far as they could by rail, arriving at Nenana, 674 miles from Nome. Three vintage biplanes were available, but all were in pieces, and none would start in the sub-arctic cold. The antitoxin would have to go the rest of the way by dog sled.

The 300,000 units shipped as far as they could by rail, arriving at Nenana, 674 miles from Nome. Three vintage biplanes were available, but all were in pieces, and none would start in the sub-arctic cold. The antitoxin would have to go the rest of the way by dog sled.

becoming the most popular canine celebrity in the country after Rin Tin Tin. It was a source of considerable bitterness for Leonhard Seppala, who felt that Kaasen’s 53 mile run was nothing compared with his own 261, Kaasen’s lead dog little more than a “freight dog”.

becoming the most popular canine celebrity in the country after Rin Tin Tin. It was a source of considerable bitterness for Leonhard Seppala, who felt that Kaasen’s 53 mile run was nothing compared with his own 261, Kaasen’s lead dog little more than a “freight dog”.

In all the annals of warfare, there may be nothing more ironic, than the time a naval force was defeated by men mounted on horseback.

In all the annals of warfare, there may be nothing more ironic, than the time a naval force was defeated by men mounted on horseback.

At least one source will tell you that this event never occurred, or at least it’s an embellished version, as retold by the hussars themselves. I guess you can take your pick. A number of 19th century authors have portrayed the episode as unvarnished history, as have a number of paintings and sketches.

At least one source will tell you that this event never occurred, or at least it’s an embellished version, as retold by the hussars themselves. I guess you can take your pick. A number of 19th century authors have portrayed the episode as unvarnished history, as have a number of paintings and sketches.

head, and seems to have begun sometime in the Neolithic, or “New Stone Age” period. One archaeological dig in France uncovered 120 skulls, 40 of which showed signs of trepanning. Another such skull was recovered from a 5th millennium BC dig in Azerbaijan. A number of 2nd millennium BC specimens have been unearthed in pre-Colombian Mesoamerica; the area now occupied by the central Mexican highlands through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica.

head, and seems to have begun sometime in the Neolithic, or “New Stone Age” period. One archaeological dig in France uncovered 120 skulls, 40 of which showed signs of trepanning. Another such skull was recovered from a 5th millennium BC dig in Azerbaijan. A number of 2nd millennium BC specimens have been unearthed in pre-Colombian Mesoamerica; the area now occupied by the central Mexican highlands through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica.

Trepanation took on airs of pseudo-science, many would say “quackery”, when the Dutch librarian Hugo Bart Huges (Hughes) published “The Mechanism of Brainbloodvolume (‘BBV’)” in 1964. In it, Hughes contends that our brains drained of blood and cerebrospinal fluid when mankind began to walk upright, and that trepanation allows the blood to better flow in and out of the brain, causing a permanent “high”.

Trepanation took on airs of pseudo-science, many would say “quackery”, when the Dutch librarian Hugo Bart Huges (Hughes) published “The Mechanism of Brainbloodvolume (‘BBV’)” in 1964. In it, Hughes contends that our brains drained of blood and cerebrospinal fluid when mankind began to walk upright, and that trepanation allows the blood to better flow in and out of the brain, causing a permanent “high”.

You must be logged in to post a comment.