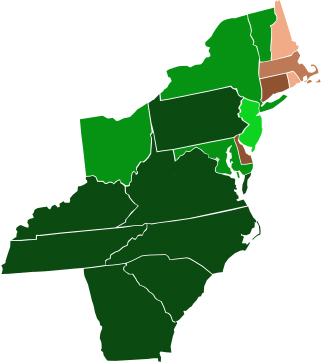

The American Revolution was barely 15 years in the rear-view mirror, when the new State House opened in the Beacon Hill neighborhood of Boston. The building has expanded a couple of times since then, and remains the home of Massachusetts’ state government, to this day.

On January 11, 1798, a procession of legislators and other dignitaries worked its way from the old statehouse at the intersection of Washington and State Streets to the new one on Beacon Hill, a symbolic transfer of the seat of government. The procession carried with it, a bundle. Measuring 4’11” and wrapped in an American flag, it was a life-size wooden carving. Of a fish.

For the former Massachusetts colony, the Codfish had once been a key to survival. Now, this “Sacred Cod” was destined for a new home in the legislative chamber of the House of Representatives.

Mark Kurlansky, author of “Cod: A Biography of the Fish That Changed the World”, laments the 1990s collapse of the Cod fishery, saying the species finds itself “at the wrong end of a 1,000-year fishing spree.”

Mark Kurlansky, author of “Cod: A Biography of the Fish That Changed the World”, laments the 1990s collapse of the Cod fishery, saying the species finds itself “at the wrong end of a 1,000-year fishing spree.”

Records exist from as early as AD985, of Eirik the Red, Leif Eirikson’s father, preserving Codfish by hanging them in the cold winter air. Medieval Spaniards of the Basque region improved on the process, by the use of salt. By A.D. 1,000, Basque traders were supplying a vast international market, in Codfish.

By 1550, Cod accounted for half the fish consumed in all Europe. When the Puritans set sail for the new world it was to Cape Cod, to pursue the wealth of the New England fishery.

Without Codfish, Plymouth Rock would likely have remained just another boulder. William Bradford, first signer of the Mayflower Compact in 1620 and 5-term governor of the Plymouth Colony (he called it “Plimoth”), reported that, but for the Cod fishery, there was talk of going to Manhattan or even Guiana: “[T]he major part inclined to go to Plymouth, chiefly for the hope of present profit to be made by the fish that was found in that country“.

There are tales of sailors scooping Codfish out of the water, in baskets. So important was the Cod to the regional economy, that a carved likeness of the creature hung in the old State House, fifty years or more before the Revolution.

The old State House burned in 1747, leaving nothing but the brick exterior you see today, not far from Faneuil Hall. It took a year to rebuild the place, including a brand new wooden Codfish. This one lasted until the British occupation of Boston, disappearing sometime between April 1775 and March 1776.

The fish which accompanied that procession in 1798 was the third, and so far the last such carving to hang in the Massachusetts State House, where it’s remains to this day. Sort of.

With the country plunged into the Great Depression, someone looked up in Massachusetts’ legislative chamber, and spied – to his dismay – nothing but bare wires. The Commonwealth had suffered “The Great Cod-napping”, of 1933.

Newspapers went wild with speculation about what happened to The Sacred Cod.

Suspects were questioned and police chased down one lead after another, but they all turned out to be red herring (sorry, I couldn’t help myself). State police dredged the Charles River, (Love that dirty water). Lawmakers refused D’Bait (pardon), preferring instead to discuss what they would do with the Cod-napper(s), if and when the evildoers were apprehended.

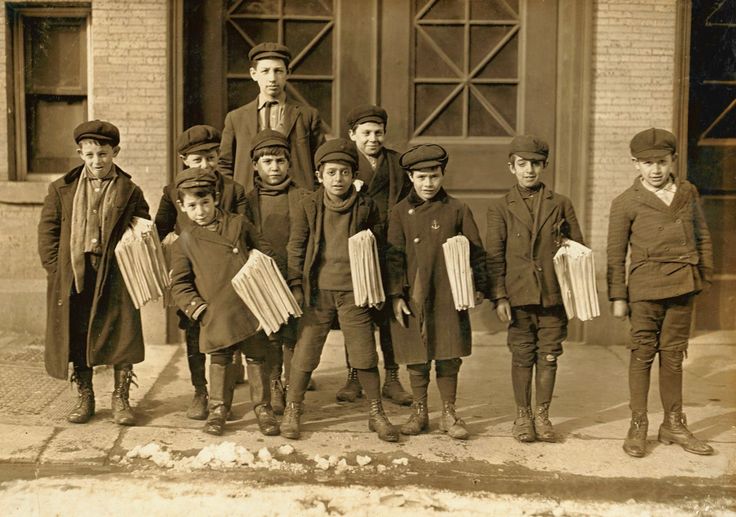

Soon, an anonymous tip revealed the culprits to be college pranksters, three editors of the Harvard Lampoon newspaper pretending to be tourists. It was a two-part plan, the trio entering the building with wire cutters and a flower box, as other Lampoon members created a diversion by kidnapping an editor from the arch-rival newspaper, the Harvard Crimson. The caper worked, flawlessly. Everyone was busy looking for the missing victim, as two snips from a wire cutter brought down the Sacred Cod.

Two days later, it was April 28. A tip led University Police to a car with no license plate, cruising up the West Roxbury Parkway. After a 20-minute low speed chase, (I wonder if it was a white Bronco), the sedan pulled over. Two men Carp’d the Diem (or something like that), and handed over the Sacred Cod, before driving away.

The Sacred Cod resumed its rightful place, and once again, there was happiness upon the Land. The Cod was stolen one more time in 1968, this time by UMASS students protesting some thing or other, but the fish never made it out of the State House.

Years later, future Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill faced the Cod in the direction of the majority party. It will come as no surprise to anyone familiar with Bay State politics, that the thing has faced Left, from that day to this. For Massachusetts’ minuscule Republican delegation, hope springs eternal that the Sacred Cod will one day, face Right.

Not to be outdone, the State Senate has its own fish, hanging in the legislative chambers. There in the chandelier, above the round table where sits the Massachusetts upper house, is the copper likeness of the “Holy Mackerel”. No kidding. I wouldn’t fool around about a thing like that.

Legend has it that, when you see those highway signs saying X miles to Boston, they’re really giving you the distance to the Holy Mackerel.

A tip of my hat to my friend and Representative to the Great & General Court David T. Vieira, without whom I’d have remained entirely ignorant of this fishy tale.

Two years later, Patriot forces maintained a similar supply depot, in the southwest Connecticut town of Danbury.

Two years later, Patriot forces maintained a similar supply depot, in the southwest Connecticut town of Danbury.

Mary Silliman was left to run the farm, and negotiate for the release of her husband. The 1993 made-for-TV movie “Mary Silliman’s War” tells a story of non-combatants, pregnant mothers and farm wives, during the Revolution.

Mary Silliman was left to run the farm, and negotiate for the release of her husband. The 1993 made-for-TV movie “Mary Silliman’s War” tells a story of non-combatants, pregnant mothers and farm wives, during the Revolution.

Later discovered by Faustulus, the boys were reared by the shepherd and his wife. Much later, the twins became leaders of a band of young shepherd warriors. On learning their true identity, the twins attacked Alba Longa, killed King Amulius, and restored their grandfather to the throne.

Later discovered by Faustulus, the boys were reared by the shepherd and his wife. Much later, the twins became leaders of a band of young shepherd warriors. On learning their true identity, the twins attacked Alba Longa, killed King Amulius, and restored their grandfather to the throne.

You must be logged in to post a comment.